From Eve to the baby born just moments ago, women are connected by an unbreakable bond. This bond speaks of strength, courage, resilience, and hope. Yet, often women’s stories have not been written by women. For many different reasons beyond the scope of this article, women’s voices have sometimes been suppressed and silenced, at the same time that the ideal of woman still continued to draw inspiration from humankind’s earliest beginnings.

However, it is possible to trace the way that artists – and the world – have looked at women through the centuries. Art is more than just the product of the artist’s imagination and skill. Art is also the product of the age in which it was created, with all its hopes and its failings, its mistakes, and its achievements. By taking a look at some of the most well-known women in history, we are also traveling through time with women and men who dreamed of a better world and did their best to make it happen. Let’s take a look at some of the most iconic women in art history, beginning with the very first.

Prehistoric Time: Venus of Willendorf

Venus of Willendorf, 24,000-22,000 BCE, Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Photograph by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The female form has been a popular subject for art since the beginning of time. Venus of Willendorf is the first depiction of a woman we know of, from 25,000 BCE. She was discovered in Willendorf, Austria, and is one of a cache of some 40 other portable statuettes, mostly female, most of them no bigger than a smartphone. This particular Venus is only 4.4 inches tall (11.1 cm), crafted out of oolitic limestone and tinted with red ochre pigment, none of it native to Willendorf. This indicates that the statuettes were made elsewhere and carried there, but to what purpose?

The emphasis on women’s life-giving attributes, such as the prominent hips and breasts, suggests that Venus was carved as a fertility symbol, perhaps a totem for good fortune, or maybe even as part of Mother Nature worship rituals. The truth? We may never know for sure.

Mesopotamia: Ishtar

Statuette of a Goddess, possibly Ishtar, Astarte, or Nanaya, ca. 300 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

From the cultures of Mesopotamia, we have the worship of the female goddess Ishtar. In her earliest form, she was known in Sumer as Inanna, as early as 4,000 BCE. It was after the reign of Sargon that Inanna and Ishtar fused into one, both a goddess of war and love, sexuality, and fertility. It is as Ishtar that she appears in The Epic of Gilgamesh, probably the oldest fictional piece of literature known to humankind.

Ancient Egypt: Nefertiti

Bust of Nefertiti, 1345 BCE, Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

One of the most famous pieces of Egyptian art is this 3,000-year-old bust of Nefertiti. Her pose is perfectly symmetrical from every angle but, unlike earlier Egyptian statues, her expression has very unique human details like slight wrinkles and even a protruding vertebra in the back. Nefertiti was a commoner at birth. Her name means the beautiful one has come, so we know her beauty was legendary even then. She married Pharaoh Akhenaton and had six daughters with him. Eventually, she became mother-in-law to Pharaoh Tutankhamun, whose funeral mask is arguably the other most famous Egyptian artifact in the world.

Today, Nefertiti’s bust rests in Berlin. It was stored away for nearly a decade during the Second World War. Then, in 1946, there was a small exhibition of high-profile works of art in Wiesbaden. Nefertiti’s bust was one of the stars, attracting 200,000 visitors – a testament to her continuing appeal.

Ancient Greece: Beauty in the Classical Age

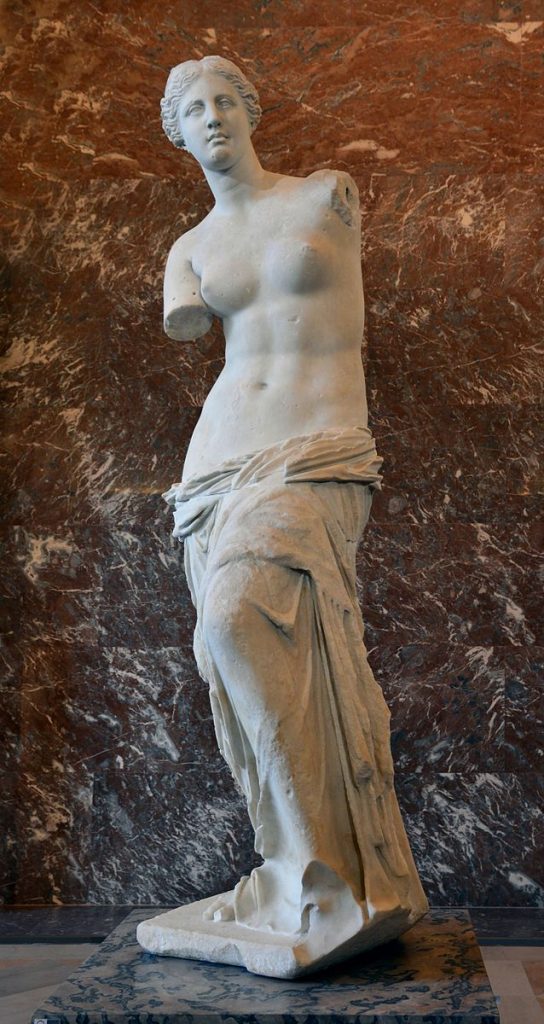

Venus de Milo, 130-100 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Photograph by Livioandronico2013 via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0).

Everybody has seen an image of Venus de Milo, she is one of the most famous women in art. Her name comes from the Greek island of Melos, where the Marquis de Rivière, the French ambassador to Greece at that time, found her in 1820. When looking at Greek statues, the viewer can identify the god or goddess thanks to the attributes they hold. These attributes are objects or natural elements, for example, Poseidon’s trident or Zeus’ lightning bolt. Venus de Milo, however, is missing her arms, which makes identification a little tricky. Is she a representation of Amphitrite, particularly worshipped on the island of Melos? Or is she Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, as suggested by her half-naked body?

Scholarly opinion leans towards the latter. She once wore jewelry but, even more than that, a hand holding an apple – one of Aphrodite’s attributes – was found near her, carved from the same Parian marble.

Bonus: The Winged Victory of Samothrace

Winged Victory of Samothrace, 190 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Photograph by Lyokoï88 via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0).

Another iconic Greek woman in art is Nike, the winged goddess of victory. Champoiseau discovered her in 1863 – an amazing find of a breathtaking statue. Champoiseau discovered 110 fragments but never a trace of her head or her arms. The statue was made of Paros marble, one of the finest in Greece, and scholars believe that her purpose was to commemorate victory in a sea battle. The dynamism of her pose as she alights on the prow of the ship and the loveliness of her form as her dress drapes around her are still awe-inspiring, even if she is broken and incomplete. She seems to be telling us to find the beauty within the imperfection and to celebrate it.

Ancient Rome: Livia’s Bust

Marble Portrait of Livia, ca. 14–37 CE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Livia Drusilla became the first Roman Empress when she married Caesar’s heir, Octavian, later known as Caesar Augustus. Hers is a fascinating story full of change, intrigue, and controversy. Biographers Tacitus and Suetonius were not kind to Livia, but they wrote almost a century after Livia died, and thus sometimes it is difficult to really ascertain what is true and what is fiction in their accounts. What we do know is that she was a child of the powerful Claudii clan. At 15, her father married her to a man almost three times her age, Tiberius Claudius Nero. Yet she must have charmed Octavian, so much so that divorce was arranged – for both of them! He married her even though she was pregnant with a second son by her former husband. Octavian adopted both boys. The older, Tiberius, succeeded him as Emperor.

Despite all the rumors, Augustus and Livia’s marriage seems to have been a happy one. She became a confidante and a very influential force in his reign as they worked together to achieve unity within the empire. They remained together until Augustus’ death at 75 years old, in 14 CE.

Ancient India: Women from the Ajanta Caves

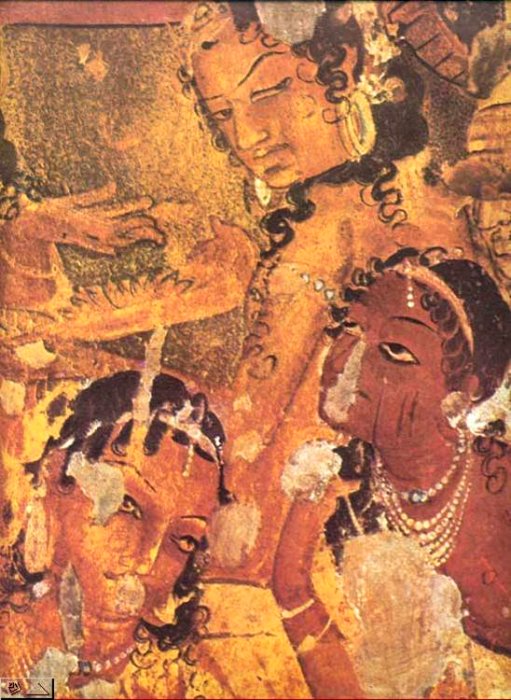

Women from the Ajanta Caves, 200 BCE-650 CE, Ajanta, Maharashtra, India. Indian-Heritage. Detail.

The Ajanta Caves are a series of about 30 Buddhist cave monuments dating from 2 BCE–480 CE, located near Ajanta village in western India. The temples are hollowed out of granite cliffs and consist of sanctuaries and monasteries. The main focus of the caves is to celebrate the life and achievements of Gautama Buddha, while also providing insight into Buddhist beliefs and values. The artists accomplished this through the depiction of legends and divinities. The sculptures and paintings constitute some of the finest examples of ancient Indian art and, even though the sculptures are very fine, the main attractions are the paintings.

The women of the Ajanta Caves offer a whole range of experience, from deities all the way through courtiers, maids, dancers, and women doing their household chores. Through these exquisite women, the artists of Ajanta give the modern viewer a glimpse into a time long-forgotten, but we find that women still lived much as they do today.

Romanesque and Byzantine Art: Empress Theodora

Mosaic of Theodora and her Attendants at the Basilica of San Vitale, ca. 547 CE, Ravenna, Italy. Photograph by Petar Milošević via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0).

Theodora rose from very humble origins to become the most powerful woman in the Byzantine world. Her early life is veiled in mystery, but the truth is probably somewhere in the middle of the official version and the account of Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea. Theodora’s father, Acacius, was a bear keeper at the Hippodrome in Constantinople. Apparently she was an actress, which may be a euphemism for a prostitute, and she also made her living as a wool spinner. Justinian was so attracted by her beauty and intelligence that he passed a special ruling legalizing unions between actresses and men of senatorial rank so that he could marry her in 525 CE.

Theodora’s influence during Justinian’s reign was such that her name is mentioned in nearly every law passed during this period. She received and corresponded with foreign envoys and rulers. Theodora also was one of the first to recognize the rights of women, passing strict laws prohibiting trafficking and altering divorce laws to give women greater benefits. She may even have saved Justinian’s crown, as well as his life, by her presence of mind during the Nika riots of January 532 CE, proving that one’s past does not determine one’s future.

Islamic Art: Girls in a Garden

Silk Velvet Textile, ca. 1600-1700 CE, The Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar. Detail.

The spread of Islam during the 7th century CE influenced the development of Islamic art through contact with the artistic traditions of newly-conquered lands. The Islamic resistance to the representation of living beings comes from the belief that this creation belongs only to God, this holds true for religious art and architecture. However, these figurative depictions are acceptable in secular art, and appear in objects as varied as textiles, manuscript illustrations, and even sculpture.

In this case, we see women in art doing everyday activities that women still do. These works provide an invaluable glimpse into the lives of women with experiences so far removed from our own, and yet so similar even through distance and time.

Ancient China: Wu Zetian

Zhang Xuan, Spring Outing of the Tang Court, 8th century CE, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China.

Wu Zetian is one of the most fascinating women of ancient China. The allure of her forceful personality and implacable character is such that her fame has endured for centuries. Even if people may not know her by name, most have heard of the controversy that has followed her all this time.

The daughter of a minor general, Wu Zetian first came to the Imperial Palace as a concubine. This honor suggests that she was very beautiful, though poorly connected. So, it seems unlikely that she would have risen to the rank of Empress. To do so, she had to go above the 28 other consorts that stood between her and the throne.

Yet, rise she did! Here is where the tale of her iron will and ruthlessness begins. She has been accused of murder, infanticide, adultery, and countless other crimes. Despite all this, she has also been praised for keeping China unified at a time when the Tang Dynasty was crumbling. Eventually, she ruled over 50 million subjects – the only woman to have ever done so in 3,000 years of Chinese history.

Middle Ages: Mary

Berlinghiero, Madonna and Child, ca. 1230, The Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Mary is at the top of the list of most painted women in the history of art. The rise of Christianity during the Middle Ages enabled the spread of images of religious nature. Among these images, Mary plays a central role as the mother of Jesus and, in a sense, mother of all believers.

The earliest representation of Mary dates from 2 CE, as a painting in the Catacomb of Priscilla, in Rome. In 431 CE, the Council of Ephesus sanctioned the cult of the Virgin as Mother of God. Soon after, images of the Virgin and Child, which came to represent church doctrine, began to appear everywhere.

The figure of the Virgin is usually known in art as a Madonna. The word “Madonna” comes from the Italian ma donna, or my lady. One very famous medieval Madonna is Berlinghiero’s Madonna and Child. Berlinghiero worked in the Byzantine style known as the Hodegetria, or she who shows the way, typical for icons that arrived in Italy following the fall of Constantinople in 1204. In this depiction, the Virgin points to Jesus as the way to Salvation.

Gothic Period: Also Mary

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà with Twenty Angels and Nineteen Saints, 1308–1311, Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, Italy.

Another iconic representation of the Madonna is called the Maestà, the Italian word for majesty. In this portrayal, the Virgin appears enthroned with the child Jesus, and may also be surrounded by angels and saints.

Duccio di Buoninsegna provides one of the most famous examples of the motif in Maestà with Twenty Angels and Nineteen Saints. In this case, the work is part of an altarpiece that was installed in Siena’s Cathedral. One of the most valuable aspects of Duccio’s piece is how his style begins to deviate from hieratic representations, which are formulaic portrayals, moving toward more realistic depictions.

Renaissance: Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Mona Lisa del Giocondo, 1503-1506, Louvre, Paris, France.

Together with Venus de Milo and Winged Victory of Samothrace, Mona Lisa is one of the three most famous women in art of the Louvre. She is probably the most famous painting in the world. Part of her appeal is Leonardo’s mastery of artistic technique, which his contemporaries began to copy – particularly the novel three-quarter pose. Maybe it is also that Mona Lisa’s home is the Louvre, one of the world’s most visited museums. Part of her fame is her circuitous route getting there, even hanging briefly in Napoleon’s bedroom. Also Mona Lisa was the victim of one of the most publicized art thefts in history. But, part of her appeal is that nobody is really, truly sure of who the sitter is!

Many scholars believe that Mona Lisa is the portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of the Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo, after whom she is also named La Gioconda. However, there are no records of such a commission from Francesco himself, so the sitter has never been conclusively identified. This has contributed to Mona Lisa’s continued mystique – she can be anyone we want her to be. She can be anything from a Florentine housewife to an enigmatic seductress and, after all, aren’t all women able to fluidly morph from one role to the next when the situation calls for it?

Baroque: Artemisia Gentileschi and Her Judith

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, ca. 1620, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes is a masterpiece of Baroque art. It has everything – drama, emotion, chiaroscuro, a biblical theme. It also has something that other paintings had not shown: women doing violence to a man.

Judith was an Israelite widow who succeeded in killing Holofernes, the Assyrian general who threatened her home. Other portrayals of the story show the dainty, delicate heroine after the deed is done. Caravaggio – Gentileschi’s inspiration –comes closest to depicting Judith in the act. However, it is Artemisia’s powerful retelling that best captures what it must have been like for a woman to fight so powerful a foe. The raw emotions conveyed through this painting have a source: Artemisia Gentileschi was a victim of rape.

Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia’s father, was also a painter and a friend of Caravaggio’s. At the time, being the daughter of a painter was the only way for a woman to receive the education that would allow her to make a living in art. As Artemisia’s skills developed, her father hired an upcoming artist, Agostino Tassi, to give her lessons. This was a decision they would regret when, in 1612, Orazio accused Tassi of rape.

The subsequent trial lasted seven months. A horrifying document survives, detailing Artemisia’s testimony of the crimes committed against her. She fought back, courageously, defiantly, during a time when women had very few recourses for justice.

Artemisia Gentileschi went on to have a very successful career that took her to the courts of Rome, Florence, Naples, and even England! Throughout her oeuvre, we see a woman’s unique point of view, a woman’s sensibilities, speaking in a world so overwhelmingly dominated by men. Her resolve to say what she needed to say led her to become the first woman to enter the Academy of Art and Design in Florence.

Neoclassicism: Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with Her Daughter, 1789, Louvre, Paris, France.

Among the exalted themes of the Neoclassical period, the self-portrait of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun with her daughter speaks to us about one of art’s truths: art is, first and foremost, about people. And, people are at the core of our world.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun was a self-taught artist. In itself, this was an unprecedented achievement, but she was also successful during a turbulent time of revolution throughout the world. Marie Antoinette, who regarded Vigée Le Brun as a favorite, helped her enter the prestigious Académie Royal de Peinture et de Sculpture – one of only four women members.

The artist had to flee France because of the French Revolution. However, she found success throughout Europe, traveling to Italy, Austria, Germany, and Russia. She even managed to exhibit at the Paris Salons while in exile. Her portraits continue to elicit admiration because of the intimacy they convey. Contemporary accounts talk about how Vigée Le Brun put her sitters at ease and engaged them in conversation while painting them. In her memoirs, she writes of the great debt she owed to art for putting her in contact with the most delightful people.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s life highlights women’s drive to succeed by leveraging their skills. In her case, her nurturing ways were not a hindrance but an asset, as she continued working for patrons who prized not only her talent but also her charm.

Romanticism: Liberty!

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (28 July 1830), 1830, Louvre, Paris, France.

Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People embodies a whole mood like few other paintings do. This painting represents the spirit of the Romantic period which attempted to evolve from an emphasis on reason during the Enlightenment, to the glorification of nature, intuition, and human emotion.

Liberty Leading the People was inspired by the revolution of 1830 when, for three days (known later as Les Trois Glorieuses), the middle-class citizens of Paris rose to fight the royal army, once more. The focus of the painting is the allegorical figure of Liberty, Marianne, a symbol of France and the French Republic. She embodies the ideals of equality, fraternity, liberty, and the people united to fight against tyranny.

The middle of the 19th century was marked by revolutions all throughout Europe. The year 1848 saw uprisings in Sicily, Sardinia, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and even England. Liberty, leading the people, reminds us of what we can all accomplish – together.

Realism: Olympia

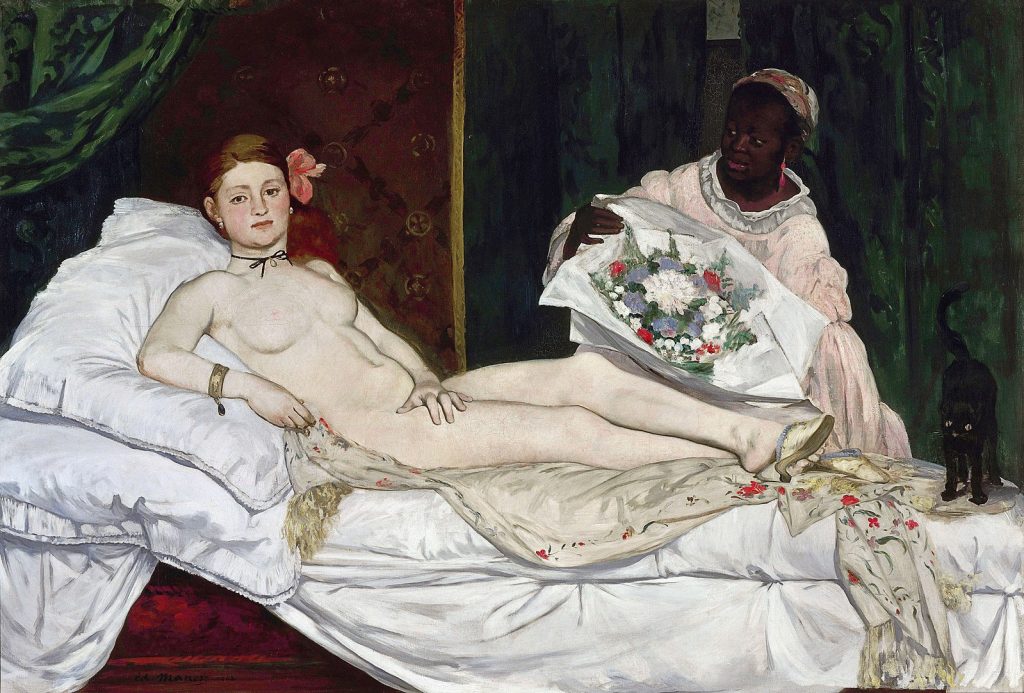

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Olympia is, perhaps, the most famous nude of the 19th century. It is difficult for the modern viewer to truly understand the shock value of this work without a little context. After all, art history is full of nudes. What makes Olympia so different is that this time, the nude is not a goddess or even a court lady but most likely a high-class prostitute.

It is difficult to know what Édouard Manet was trying to say when he painted this work. Or what he expected would happen when he entered the canvas at the Paris Salon of 1865. It is also difficult not to see a jab at society’s hypocrisy of exalting times past while refusing to see what was right under their nose.

Victorine Meurent was the model for Olympia, while model Laure posed as her servant. Meurent modeled several times for Manet. We also see her in The Railway, and Les Bains, more commonly known as Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, one of those paintings that changed the course of art. After Les Bains came to light, Meurent was highly criticized and even called the ugliest woman in Paris. That makes her decision to keep posing for Manet, again and again, both courageous and also a little baffling.

Some scholars suggest that the most arresting aspect of Olympia is her confrontational gaze, which seems to be the height of defiance against the stifling patriarchy of the 19th century. Whatever the case, Meurent’s – and Olympia’s – daring still invites us to boldly take a stand.

Pre-Raphaelites: Ophelia, Elizabeth Siddal, and the Pre-Raphaelite Muses

Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia, ca. 1851, Tate Britain, London, UK.

Pre-Raphaelite art was a golden age for portrayals of women. These fabulous muses were often the painters’ own wives or mistresses. Furthermore, they have come to define a whole artistic movement through their very distinct expressions and characteristics.

The Pre-Raphaelite painters sought to portray the world as realistically as possible. For that reason, they abandoned the practice of sketching different features from different models to assemble a perfect face. Instead, they painted women exactly as they were. Looking at portrayals of Victorian women, their faces are sweet, good-natured, and delicate, their bodies plump and maternal. Not the Pre-Raphaelite women! These girls had strong jaws and wide mouths and big hands and direct gazes, and people did not like how they looked.

Elizabeth Siddal was one of these muses who appeared again and again throughout the Pre-Raphaelite’s work. Hers was a working-class background but, as she came into contact with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, she began to develop her eye for art and painting. Her longing to stand on her own as a woman, and a painter, prompted her to leave her partner, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She hoped to develop her art on her own, free from his influence and his patronage.

She was not the only one of the Pre-Raphaelite muses who were artists themselves. Jane Morris, for example, was an artist in the Arts and Crafts movement. To her contemporaries, however, she never could quite escape the shadow of her more famous husband, William Morris. These strong women were considered ugly and openly criticized, yet they defied all conventions by standing tall and pursuing their deepest yearnings.

Impressionism: Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle, 1872, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Berthe Morisot is one of the three great ladies of Impressionism, along with Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt. One of the things that sets Berthe Morisot apart is that she embraced the movement early on, becoming the only woman to exhibit in the first Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. To have so readily rejected the academicism of the Salon, throwing her lot with a group of “unsuccessful painters,” Morisot must have been quite a forward-thinking, independent, adventurous soul.

Yet, despite her strong convictions, she gave us a unique window into what it meant to be a woman at the end of the 19th century. During her life critics praised her feminine grace. They described her art as flirtatious and charming. Even though nobody thought to give labels to any of her male contemporaries, Morisot did not apologize. She gave us women on walks, in their gardens, dressed up to go to balls, or playing with their children. Morisot painted outdoors and also interiors. She painted both landscapes and still-lifes. In short, Berthe Morisot painted what she felt like painting, refusing to be defined by just one facet of her life. Why couldn’t she be everything? Why can’t we?

Post-Impressionism: Pointillist Women and Other Muses with Different Looks

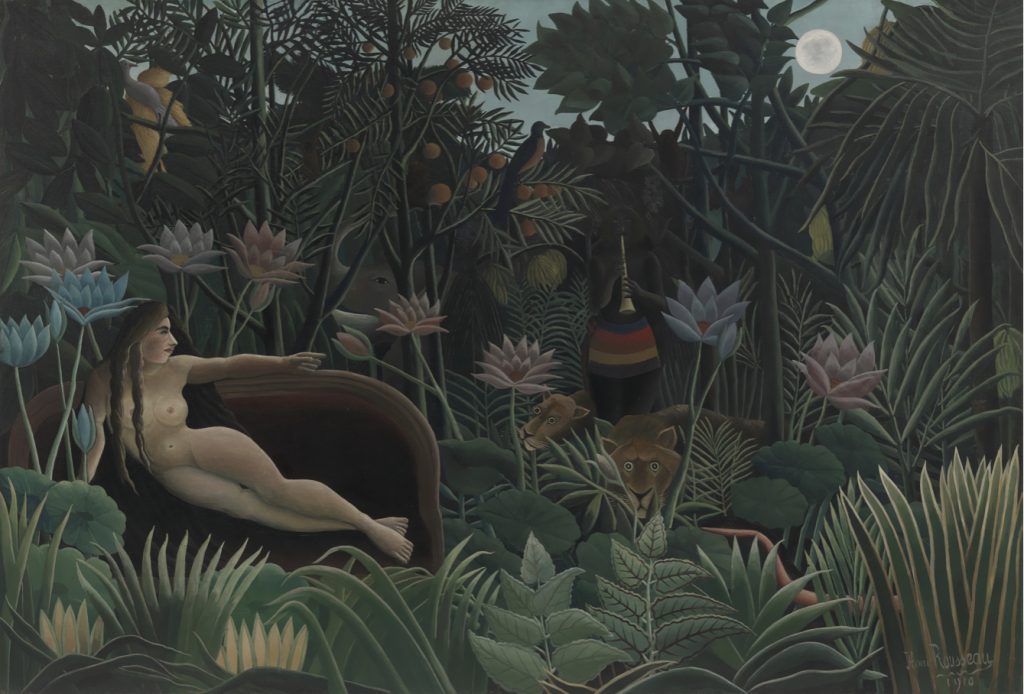

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

In early Post-Impressionism experiments, painters were not only interested in subject matter from the everyday. They were also interested in different techniques to portray this reality. However, by the end of the period, they had moved on to realities even beyond the ones they could see with their eyes

Seurat’s pointillistic depictions of Parisians and their daily life invite the viewer to truly consider what it is that he or she is seeing. Are those colors, shapes, or maybe both? And how are they perceived? Paul Signac said of this technique:

…the separated elements will be reconstituted into brilliantly colored lights.

Quoted in “Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism“, The Metropolitan Museum.

The statement is in the revelation of color and its perception, moving beyond shocking subject matter to reveal a new reality.

Henri Rousseau’s The Dream transcends from that new reality into realms that people can only access subconsciously. But does that make them less real? Rousseau said of this painting:

The woman asleep on the couch is dreaming she has been transported into the forest, listening to the sounds from the instrument of the enchanter.

Quoted in “Henri Rousseau“, MoMA.

In this painting, woman as a primeval force shines in all her glory.

Symbolism: Klimt’s Judith

Gustav Klimt, Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria.

The emphasis in this portrayal of Judith is not on her brave deed, but in the seduction that preceded it. The Symbolist Judith has more of the femme fatale than the widow in her. She captivates viewers even today because of all the emotions that coalesce in her intense expression. Critic Franz A. J. Szabo described the painting as a symbol of:

… triumph of the erotic feminine principle over the aggressive masculine one.

Quoted at “Judith and the Head of Holofernes“.

The muse behind this enticing painting was a Viennese socialite called Adele Bauer. At 19, her father married her to Ferdinand Bloch, 17 years her senior. Bloch adored her so much that he made her last name part of his own, both becoming Bloch-Bauers.

Bauer went on to model several times for Gustav Klimt and in each depiction Klimt managed to capture different aspects of her fascinating personality. Sometimes she appears as a triumphant queen. Sometimes she appears mature and melancholic. In all her portrayals, her intelligent, direct, powerful gaze invites the viewer to look again and, perhaps, to keep on looking.

Fauvism: Amélie Matisse and Her Green Stripe

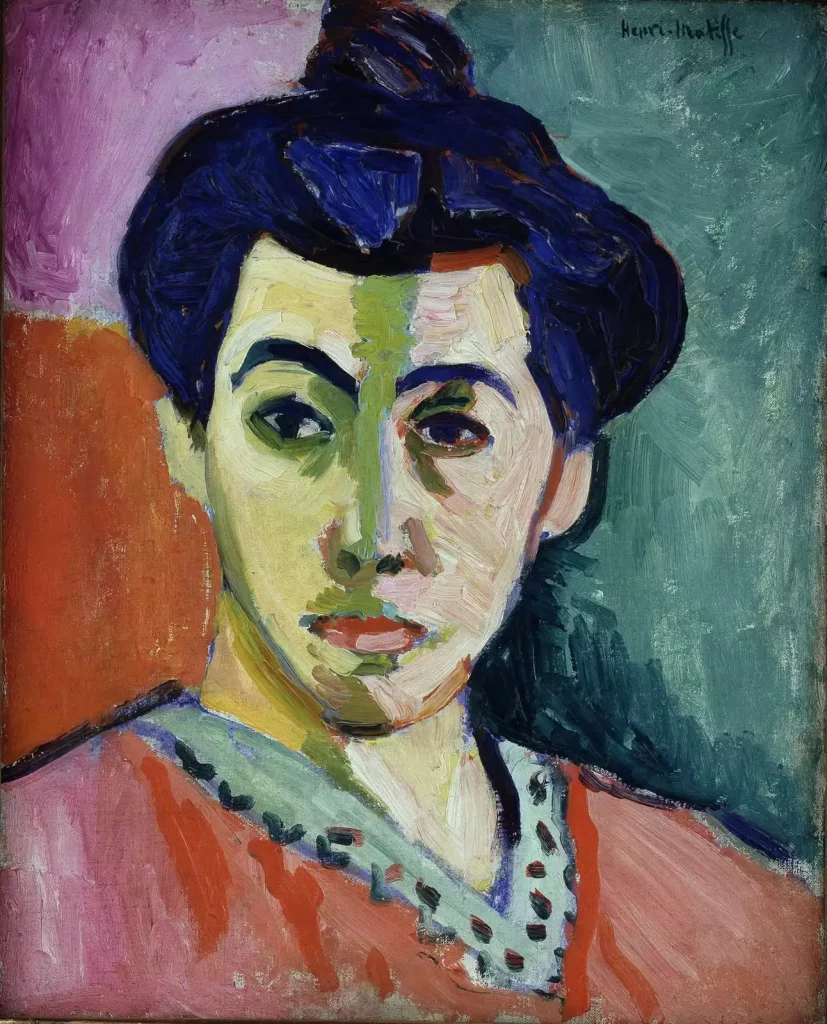

Henri Matisse, Portrait of Madame Matisse. The Green Line, 1905, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Green Stripe is one of the most famous portraits of the 20th century. Henri Matisse used only color to describe the image – there is no shading as such, no traditional light and shadow definition. All of the contouring is done through the different colors used. The green stripe down the center of the face acts as an artificial shadow of sorts, dividing the face into a cool and warm side, light and dark. The bright and vivid complementary hues create both impact and, surprisingly, harmony.

The muse behind this modern masterpiece was none other than Amélie Matisse, the artist’s wife. The two met, of all places, at a wedding and themselves married shortly afterwards. Matisse was absolutely committed to his art. Amélie understood this about him and accepted it, working hard to ensure that he had what he needed to succeed. She acted not only as his wife but also as his manager. In later years, Matisse began to need more independence and their marriage eventually dissolved. Still, all his portraits of Amélie present a dignified, poised, intelligent woman, gazing directly at the viewer, meeting the world and all its challenges head-on.

Expressionism: Wally

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Wally Neuzil, 1912, Leopold Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Wally’s face gazes at the viewer – or maybe at the painter? With a straightforward gaze, a little innocent, a little curious, maybe a little playful. The power of her penetrating eyes is still strong, even a hundred years after they were painted.

Walburga Neuzil, or “Wally”, was Egon Schiele’s model, muse, manager of sorts, and lover. It is unclear how the two met, but it is very possible that Gustav Klimt introduced them. Schiele was Klimt’s protégé, and Wally was Klimt’s model. At first, Schiele paid Wally for her modeling but eventually, the relationship deepened. She was unwaveringly loyal to Schiele, supporting him during many dark times. The only problem – Wally was not an advantageous marriage prospect. Schiele decided to propose marriage to Edith Harms who lived across from his studio in Vienna.

Schiele and Wally had lived very unconventionally until that point. However, Schiele’s proposal that they continue to see each other after his marriage was unacceptable to her. Wally ended the relationship and left, never to see him again. Schiele painted Death and the Maiden after this event, perhaps as an homage to his muse, perhaps as his attempt to let go.

There is evidence that there was some contact between them through letters, and Schiele may even have sent her money, but Wally worked hard to move on. She became a nurse during the First World War, a very heroic act that cost her her life, as she contracted scarlet fever and died in 1917. Wally was only 23 years old when she died, yet in her short life, she packed a world full of experience. She was described as Schiele’s shadow but in Portrait of Wally we see only her and her strength.

Cubism: Ladies of Avignon

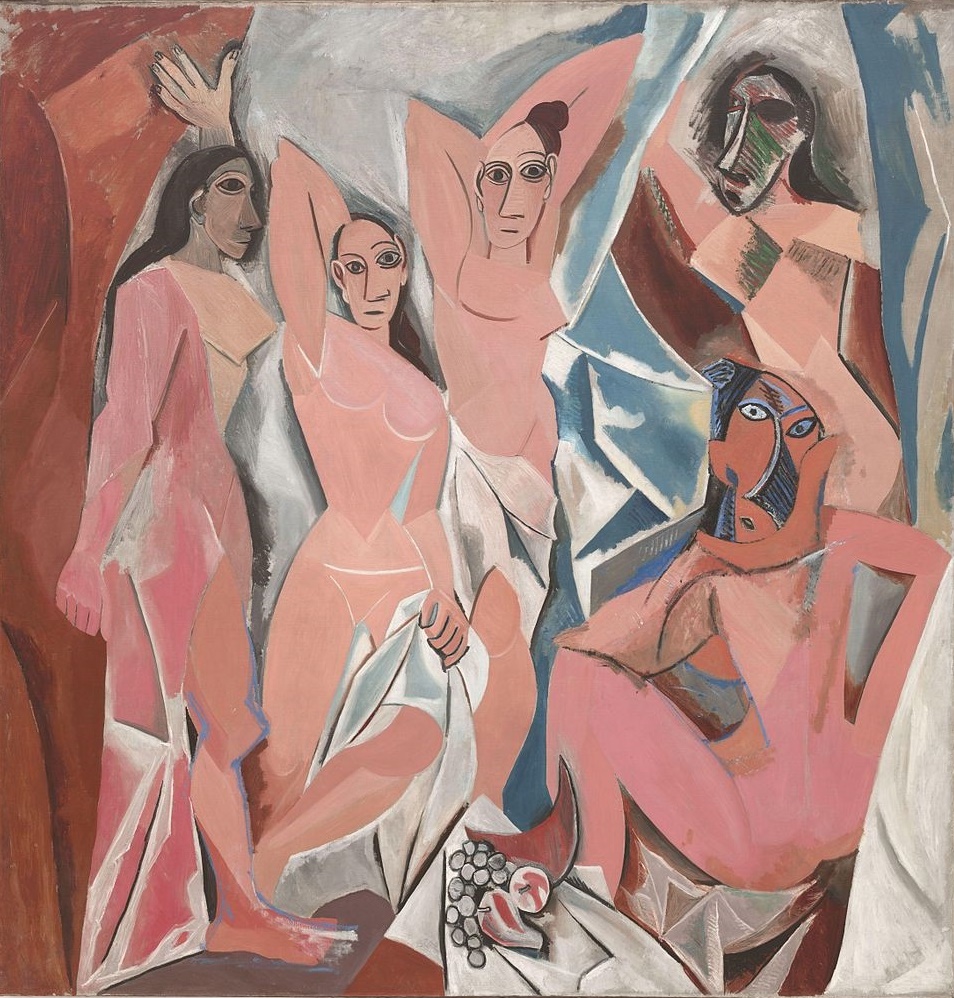

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

The Young Ladies of Avignon is another one of those works that changed the history of women in art. Picasso’s models were a group of five prostitutes from a brothel on Carrer d’Avinyó, a street in Barcelona, Spain. The painting was radical for its subject matter and for its treatment of the figures in a disjointed, angular fashion. Picasso also chose to include unusual elements for the time through his addition of African mask-like features, while the figure on the left presents almost Egyptian in treatment. Added to this was the large format, at 7.9 x 7.6 in (243.9 × 233.7 cm), to make for a very unusual painting that disconcerted everybody and garnered adverse criticism. Even Picasso’s friends did not like it.

Georges Braque was one of these people. Even though the primitive, almost savage force of the figures was initially so shocking, Braque studied the work in great detail, perhaps more than anybody else. This study led him to experiment with a new art style that would later be known as Cubism. We will never know who these ladies truly were, but they inspired one of the most significant revolutions in modern art.

Futurism: Dancer at Pigalle

Gino Severini, Dancer at Pigalle, 1912, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD, USA.

The human figure is not among the most depicted themes by Futurist artists. Futurism was concerned with the dynamism of modern life so the usual subject matter was a modern object from the time period, such as cars, trains, steamships, etc. However, artist Gino Severini became fascinated by dancers and, uniquely among the other futurists, he gave them full treatment for years. In all, he produced over one hundred works depicting dancers.

His Dancer at Pigalle captures the exuberance of living in Paris in the early 20th century. Back then, every evening intellectuals, writers, artists, and musicians gathered in the streets of bohemian neighborhoods and in famous places such as Le Chat Noir, or the Moulin Rouge. Pigalle was one of these places and Severini’s girl still seems to be twirling and dancing the night away.

Abstractionism: Gaea

Lee Krasner, Gaea, 1966, Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan, New York, NY, USA.

The object of Abstract Art is to strip away all the inessential elements. With that in mind, an abstract artist’s look at women is particularly enlightening in a survey of women through the ages. Every artist would have their own opinion of what the essential elements are. These would also vary depending on the school of thought. Suprematism, Minimalism, Op Art… all of these looked at women differently.

Lee Krasner’s Gaea embodies explosive energy and color, yet also a curious beauty and harmony within all the elements. Gaea is the Greek personification of the Earth as a goddess. So, in effect, Krasner is trying to get to the very primeval core of what it means to be a woman. She said of this painting that she was drawing from sources that are basic when she created it. The overall effect of this large 5.9 x 10.6 in canvas (175.3 x 318.8 cm) embodies woman’s original energy and essence.

Dadaism: Woman and Soap

![Women in art: Beatrice Wood, Un Peut d’Eau dans du Savon [A Little Water in Some Soap], 1917, American Museum of Ceramic Art, Pomona, CA, USA.](https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/46F953EF-CD37-4E73-A1A3-F5586442891D.png)

Beatrice Wood, Un Peut d’Eau dans du Savon [A Little Water in Some Soap], 1917, American Museum of Ceramic Art, Pomona, CA, USA.

Dada was an irreverent movement that was born in reaction to the horrors of the First World War. One of the most famous works from this time period is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, which he submitted to the Society of Independent Artists’ exhibition. To this same exhibition, Duchamp’s friend Beatrice Wood submitted a work titled Un Peut (Peu) d’Eau dans du Savon (A Little Water in Some Soap), causing just as much of an uproar. Perhaps even more so, because a woman should never express herself in such a vulgar, provocative manner.

Wood, however, had a bit of a rebellious streak and she recreated this work again on paper, then in clay, likening the woman to the main figure of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, as she emerges from out of the foam. The work is just as intriguing, curious, and puzzling as the artist who produced it.

Surrealism: Woman Through Woman’s Eyes

Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait, 1937-1938, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait offers a unique perspective of how a woman sees herself. Carrington spent her childhood surrounded by animals at her father’s estate, reading fairy tales and legends. She drew on these experiences as an adult to produce her art. Self-Portrait is full of symbols and curious things to look at. She presents herself in jodhpurs, which were worn while riding horses, yet she is not herself riding. There is a rocking horse above her and a horse running free, away in the background. Her hair is wild and unbound, yet she sits in a refined interior. During interviews, Leonora Carrington mentioned that she identified with the hyena in her insatiable curiosity, and in their mirrored gestures one can read that identification.

What was Leonora Carrington expressing through this enigmatic work? Rebellion? Confinement? Breaking free? All of her emotions? None? Perhaps the point is not to know but to feel, and women looking at it can feel along with her.

Art Deco: Tamara de Lempicka and Her Green Bugatti

Tamara de Lempicka, Autoportrait (Self-Portrait in a Green Bugatti), 1929, private collection, Switzerland. Tamara de Lempicka.

One of the most famous female self-portraits is Tamara de Lempicka’s Autoportrait (Self-portrait in a Green Bugatti), though this is not the only self-portrait she ever painted. The work was commissioned for a German fashion magazine called Die Dame, in English The Lady. One of the things that makes it so fascinating is that here the artist shows herself as she wishes to be seen. The elegance, the allure, the sophistication of the portrait are all undeniable and powerful, even today.

It is curious that Tamara De Lempicka actually drove a yellow Renault, yet she painted herself in a green Bugatti – a racing car – wearing a leather helmet and gloves, wrapped in a scarf that floats in the wind as she races ahead. Even now, one can feel her independence and self-assurance, her single-mindedness in pursuing her goals. A woman’s capacity to invent herself and go after her dreams is legendary. In her Autoportrait, de Lempicka gives us one version of it.

Pop Art: Marilyn Monroe

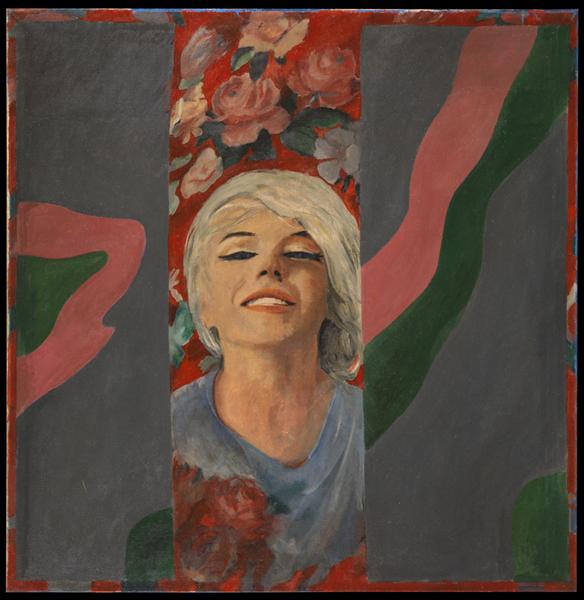

Pauline Boty, Colour Her Gone, 1962, Art UK, London, UK. WikiArt.

Marilyn Monroe is, perhaps, the first image that comes to mind after hearing the words Pop Art. Andy Warhol immortalized her in his iconic Marilyn Diptych. He chose a photo that almost anyone would recognize from the movie Niagara and reproduced it 50 different times.

It is hard to miss his meaning. Marilyn Monroe died in 1962, the same year he worked on his diptych. Through his work, he seems to be asking us not to forget that behind this symbol created by society, there was a real woman. The work is poignant in many ways and difficult to discuss considering its timing.

Another Pop Art artist, Pauline Boty, also recreated Marilyn Monroe in her work. Her canvas Colour Her Gone, also from 1962, offers a very different take on the same subject. Pauline Boty presents Marilyn Monroe in a casual, relaxed pose, not an iconic one, wearing a plain baby blue top. The contrast between this image and the far more sultry and sexualized depictions in other artists’ works is a message in itself, and perhaps not a very different one.

Pauline Boty’s work is asking us to look at the real person too – the real woman underneath all the trappings and all the fame and all the world’s eyes on her. She was just a girl, and she could be any girl. The poignancy of the message is all the more powerful coming from another woman.

Looking Forward

A woman is like a tea bag; you never know how strong it is until it’s in hot water.

Women have lived so many lives since the beginning of humanity – some tragic, some joyful. All unique. Valuable. Important. Let us remember the strength of women everywhere, the ones we know, the ones we hope to be, and the ones we have never met but whose contributions have brought us to where we are today. Those who have, and who are, paving the way for where we’ll be tomorrow.

Here’s to strong women: may we know them, may we be them, may we raise them.