Shiva Nataraja – The Hindu Lord of the Dance. Iconography and Symbolism

Nataraja, the manifestation of the Hindu god Shiva as the Lord of the Dance, holds a profound significance in Hindu mythology and symbolism. Depicted...

Maya M. Tola 3 June 2024

From its beginnings in India, Buddhist art has traveled across cultures. Buddhism developed its character thanks to many pilgrims who made their journey to the east and west to propel the ideas. Although it no longer has a strong presence in the land of its birth, Buddhism still thrives in its various forms in many countries.

Over the past 2,500 years, Buddhist art has deeply influenced the evolution of Asian civilization. As it spread across cultures, Buddhism absorbed indigenous beliefs and incorporated a wide range of imagery into its art and religious practices. Since images were central to Buddhism, many pilgrims had to go the extra mile to bring works of art and Buddhist texts back to their native lands.

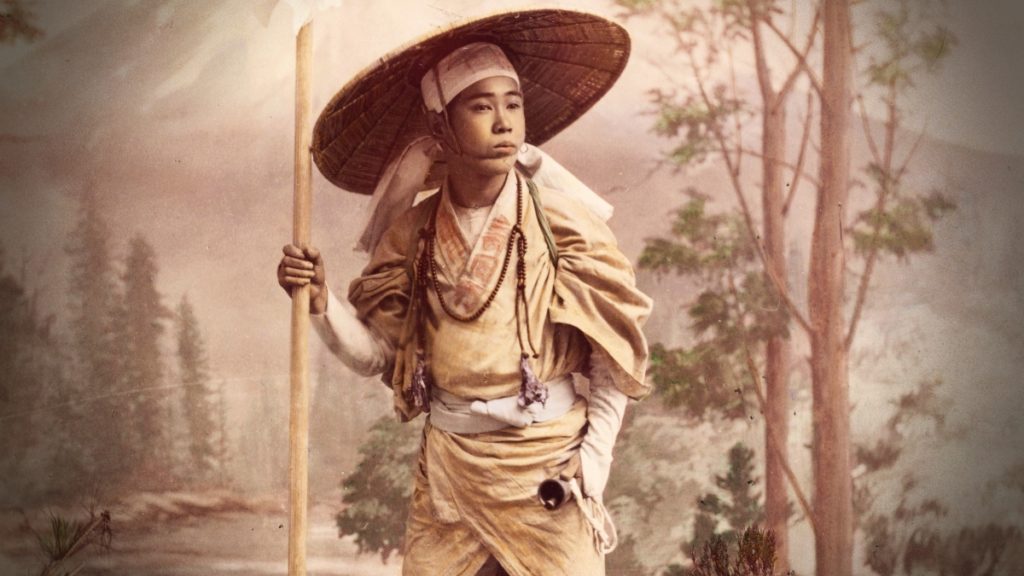

Xuanzang, a fearsome Chinese Buddhist monk, was one of these travelers. Hoping to go to the holy land of Buddhism in India and to obtain the true scriptures, he left his town and went on the journey across countries in 629 CE. He departed in secret by night, safely passing five watchtowers in the desert and the Jade Gate, the last outpost of the Tang empire. However, this solitary pilgrim was still in danger. He was going against the wishes of Emperor Taizong (reigned 626-649).

At the time, the emperor had little sympathy for Buddhism. He did not want his subjects to venture into dangerous regions. Besides, his power was far from secure. His diplomacy was still grappling with the hostility of the Central Asian people. Disobeying the emperor was risky and dangerous. Then, why did Xuanzang determine to go the extra mile on his pilgrimage from China to India? Perhaps, he was thinking about another ‘pilgrim’ from the past who also left his residence and started his journey. This traveler was Siddhartha Gautama.

According to tradition, Siddhartha was the founder of Buddhism. His name means “he who achieves his goal”. He was born a prince of the Shakya clan in Lumbini, now in Nepal. Some scholars have questioned the long-accepted dates of Siddhartha’s birth and death, 563-483 BCE. They believe that he may have lived and died as much as a century later.

The Gandharan relief depicts the prince’s miraculous birth. The Hindu god Indra offers a cloth and attends the Buddha’s birth from his mother’s side. Queen Maya, the mother of Siddhartha, has the garments and hairstyle of a Roman matron. She stands in an Indian posture associated with female nature spirits who grasp tree branches to make them bloom.

Siddhartha probably did not envision what role ancient Gandhara played in the development of Buddhist art. Gandhara was in present-day north-west Pakistan and northeast Afghanistan. It had ties to India, western Asia, and the Hellenistic world.

From the middle of the 1st century to the 3rd century CE, Gandharan artists synthesized elements from many cultural regions. As a result, they created an image of the Buddha combining Greco-Roman ideals of beauty with Indian Buddhist concepts and iconography. The Gandharan influence spread all over Asia. Its traits can be seen, for example, in Chinese Buddhist sculptures.

Siddhartha seemed destined for an extraordinary existence. Shortly after the prince was born, the sage made his predictions. The boy would become either a great king or a great spiritual teacher. Suddhodana, the chief of the Shakya clan, wanted his son to become a ruler. Therefore, he surrounded Siddhartha with luxury and comfort to prevent him from seeing any misery.

However, the quest for knowledge eventually overcame the security of a wealthy life. Siddhartha left the palace for the first time at the age of twenty-nine. Outside, he encountered an old man, a sick man, and a dead man. From that moment, he was determined to seek deliverance from the suffering.

After the event, Siddhartha met a monk who was begging for alms. This monk appeared to have an inner tranquility that Siddhartha had never witnessed. Moved by the suffering he saw, the young prince abandoned his luxurious existence for a life of ascetic practice. Siddhartha left his family’s palace. He embarked upon a new life as an itinerant monk.

On his path to enlightenment, Siddhartha spent six years as an ascetic, trying to conquer the innate appetite for comfort. At some point, he was near death from vigilant fasting. However, a young girl offered him a bowl of rice. After accepting it, Siddhartha had a revelation that physical austerities were not the means to achieve spiritual liberation. Then, he sat and meditated beneath a ficus tree.

When Siddhartha approached the moment of omniscience, demons tried to distract him. He calmly touched the earth to witness his attainment of enlightenment. This gesture or bhumisparsha mudra signals the moment. That night Siddhartha reached enlightenment and became the Buddha or “the awakened one”.

Depicted in art, the Buddha has the characteristic circular dot or urna on the forehead. It symbolizes a third eye, an ability to see past our mundane universe of suffering. The ushnisha or the crown of hair is the three-dimensional oval at the top of his head. Overall, artists can employ in their works 32 major and eighty minor auspicious marks or lakshanas of the Buddha. They all signify his immense spiritual capacity.

At the top of the stele or stone slab, there are the branches of the ficus tree with its heart-shaped leaves. There, Shakyamuni, or “sage of the Shakya clan”, achieved enlightenment. The tree became known as the “enlightenment” or bodhi tree. Two other Buddhas flank the central figure.

In the Buddhist worldview, time is beginningless. Therefore, there were many Buddhas in the past and many more will appear in the future. Theoretically, the number of Buddhas having existed is enormous. They are often collectively known as “Thousand Buddhas”. For example, Dipankara is one of the past Buddhas, while Gautama was the most recent. Maitreya will be the Buddha in the future.

In many of his past lives, the Buddha was reborn as a bird or an animal. However, irrespective of the form, he always had great wisdom and compassion. More than five hundred stories, Jataka Tales or “birth stories”, portray the Buddha in one of his former lives. A jataka story reveals some elements of the Buddha’s teaching, usually a moral point. For example, the story of the Monkey King emphasizes the importance of self-sacrifice and putting other people before yourself.

Buddhist artists often depicted forces of nature in their works. For example, the sculptor included several elements in the stele with the Buddha calling on earth to witness. Flying above the Buddha, are the two monks. They have achieved an advanced stage in monastic practice. Consequently, they were able to overcome the forces of gravity and control nature. Below the Buddha, are the lions of the throne. The roaring of the lions is like the teachings of Shakyamuni himself.

Furthermore, the Buddha sits on a lotus pedestal. A lotus grows in muddy water. It is in this environment that the flower gets its meaning. The lotus also resembles the purifying of the spirit which is born into murkiness. One can rise above the murk to achieve enlightenment. Thus, those who are working to rise above the muddy waters will need to be faithful followers.

After his enlightenment, the Buddha walked to the city of Varanasi. Then, he went to a deer park in Sarnath. There, he met five renunciates with whom he had previously practiced asceticism. For the rest of his life, he was an ascetic mendicant. He preached and meditated in northeastern India, in what is now Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Siddhartha set about teaching them what he had learned. He encouraged his disciples to follow a path he called “The Middle Way”. It is a path of balance rather than extremism. Shakyamuni presented himself as a teacher and not as a god or object of worship. Traditional accounts say that he died at the age of 80. When the Buddha died, he attained parinirvana, or a state of nirvana after death.

The artist depicted the Buddha facing westward in a final trance after a long life of teaching. In the painting, the golden body of the Buddha bears the marks of his way to enlightenment. For example, the short curls on his head show his ascetic life. Elongated earlobes adorned with heavy jewelry reflect his birth as a prince. The ushnisha and urna attest to his penetrating wisdom.

In contrast with the image of Buddha, those witnessing the Buddha’s parinirvana reveal their own imperfect level of enlightenment. It is shown in the extent of their grief. Men and women of every class, joined by more than thirty animals, are weeping bitterly. Shaven-headed disciples also mourn, as do the multi-limbed Hindu deities and guardians. Finally, they started to follow the Buddha’s teaching. Even the blossoms of the sala trees change their hue as Queen Maya descends weeping from the upper right.

After the Buddha’s death, generations of thinkers started to move forward the Buddhist ideas and art. However, these pioneers lived in the Hindu world. By that time, Hinduism had amassed an extended pantheon of gods and had a rich body of literature and art.

As a religion, Hinduism did not have a single founder. The fundamental religious texts of Hinduism were Vedas, four collections of hymns. The earliest part of hymns date from about 1400 BCE. The Upanishads, one of the Vedas, composed around 700-500 BCE, engage in profound philosophical speculation about life.

Hindus, and later Buddhists, described the concepts related to life and death in their texts. One of the concepts is karma. It implies that one’s actions determined the level of the soul’s rebirth after death. Furthermore, our earthly form is based on merit piled throughout our lives. Thus, for a better future life, actions in our present life matter. The Buddha realized that suffering was inevitable within the cycle of rebirth or samsara.

In the roundel with karma lineage, the monks appear in the robes in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. The central figure is likely Mikyo Dorje (1500–1599), the eighth head of that lineage. The other seven monks portray earlier incarnations of him. They include Marpa (1012–1098) and Milarepa (1040–1123). Vajradhara, the primordial Buddha, presides above. Below stands Mahakala, the order’s great protector.

To attain liberation from repeated rebirth is to break away from the cycle and enter into nirvana. Four Noble Truths, formulated by Buddhist thinkers, explain how we can achieve nirvana. Perhaps, they are the basis of the Buddha’s teaching.

They tell us that existence is suffering. This means that we do not find ultimate happiness or satisfaction in anything we experience. The cause of suffering is craving, implying that we tend to grasp things or push them away. Consequently, we find ourselves at odds with the way life really is. The cessation of suffering comes with the cessation of craving.

We cannot change the things that happen to us. Still, there are methods through which we can change our responses. For example, the Noble Eightfold Path can lead us from suffering to nirvana through moral conduct, contemplation, and wisdom. The Buddha’s teaching is like rafts crossing the sea of suffering to reach the shores of Nirvana.

In this context, nirvana marks the end of rebirth by stilling the fires that keep the process going. In due course, in Hindu philosophy, nirvana can be the union of Atman or the inner self with Brahman or the highest Universal Principle. Thus, the Buddha challenged the aspect of immortality in Hinduism.

After the death of the Buddha, his followers met in a series of councils. According to the tradition, Mahakasyapa, his disciple, presided over the first council in about 400 BCE. Each council tried to settle disputes about what the Buddha had taught and what rules the monastic order should follow. This way, the thinkers helped to develop the early form of Buddhism.

In this work of art, Mahakasyapa stands with closed eyes. He has an expression of meditative concentration. His head is enclosed within a halo, symbolizing the monk’s wisdom. This feature was probably introduced into Buddhist iconography from Iran. Mithra was the Iranian god of light with a halo. Later, his cult spread from India in the east to the Hellenic world in the west.

The disciple is holding a reliquary for the Buddha’s ashes. They symbolize the Buddha entering nirvana at death. The artistic simplicity exemplifies the spiritual content of this figure. Gandharan influence is revealed in the way the artist sculptured the folds of the drapery.

Initially, monks passed down Buddhist ideas orally. After a while, they started to write sutras or a collection of aphorisms in the form of a manual. The masters compiled texts in Indo-Aryan languages, such as Pali and Sanskrit. These languages belong to the Indo-European language family, rich in grammatical forms. In ancient and medieval India, Sanskrit became the lingua franca or bridge language for the transmission of Buddhist ideas.

To transmit ideas, pilgrims had to overcome the language barrier. In other countries, usually people spoke different languages. For example, Chinese is a monosyllabic and uninflected language. Its script is based on an ancient tradition. It is not quite suited for expressing abstract thought.

Therefore, monks often had to learn languages, most commonly, Sanskrit. They also set a formidable task for themselves to produce new vocabulary. However, by interpreting the Buddhist texts, they further developed the concepts of Buddhism.

Buddhist traditions divide texts into several types. First, buddhavacana or the “word of the Buddha” are the sutras or scriptures. Shastras, or precepts, rules, or treatises, represent another group of texts. Shastra has a similar meaning to an English suffix “-logy”, implying knowledge of a particular subject. Finally, abhidharma is an abstract and technical systematization of the Buddhist doctrine.

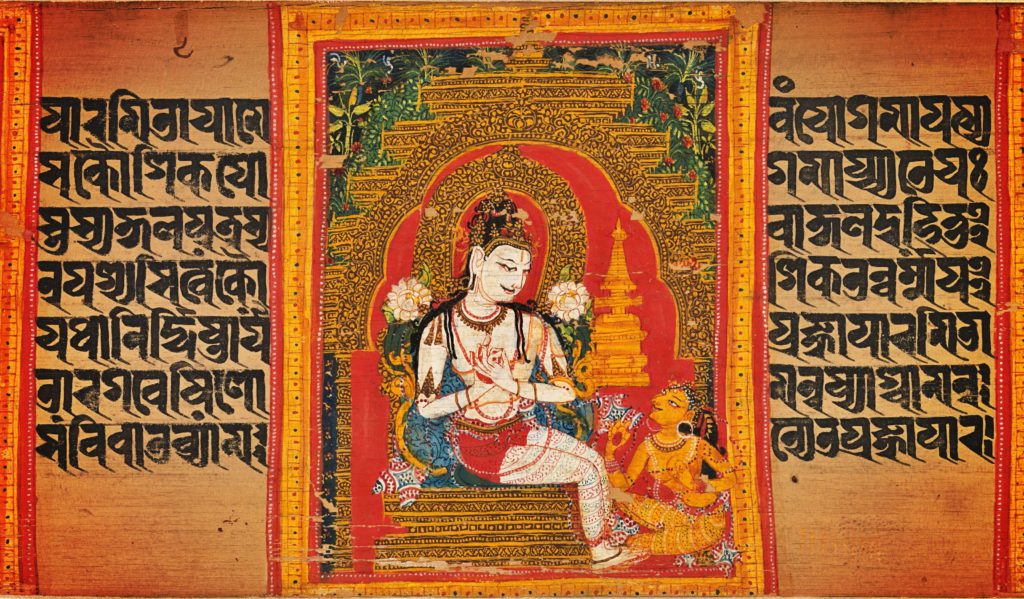

In the manuscript, Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, is depicted sitting in the temple. His hands are held in double vitarkamudra or the preach gesture to the female devotee who looks up at her savior. In this scene, the psychological drama follows textual prescriptions on how devotees should gaze on the deity. The depiction of a stupa or reliquary evokes the Buddha essence or dhatu. It embodies the presence of both the Buddha relics and Buddha teachings.

The production of images in Buddhist art began with the death of Shakyamuni. The cult of the Buddha’s presence was possible only in his absence. The Buddha himself did not appear in the early images. Nevertheless, early artists used a range of visual symbols to reveal Buddha’s teachings. For example, they showed Buddha’s presence with a footprint, an empty seat, a parasol, or another sign. These symbols were visual prompters for correct veneration. Still, there was no prohibition against depictions of the Buddha.

Furthermore, Buddhists believed that the images are presentations not representations of the Buddha. Artworks were like living beings with the power to embody his presence. After a while, communities started to build stupas or reliquaries. There, they enshrined the Buddha’s remains.

As a result, stupas became a powerful symbol of both Buddha’s death and continued presence in the world. From the third century BCE, large stupas rose as part of the monastic complexes. The sites like Bharhut and Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh are the most well-known.

The Great Stupa at Sanchi is also one of the oldest stone structures in India. The emperor Ashoka (reigned c. 268–232 BCE) commissioned this stupa. Its nucleus was a simple hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha. The stupa has the chhatri, a parasol-like structure. It symbolizes high rank, which was intended to honor and shelter the relics.

The torana or ornamental gateway of this smaller stupa is dated to the first century CE. The reliefs are in the same style as those on the gateways of the Great Stupa. Architrave posts, or “false capitals”, are roughly square-shaped. They are at the junction between the architrave and pillar, and between the architraves themselves.

Building on the scriptures, artists further materialized Buddhist concepts in art. Almost all Buddhist temples have images. The earliest surviving Buddhist sculpture dates to roughly the third century BCE. The Buddha, bodhisattvas, minor divinities, and monks adorn the temples.

For the community, making and seeing Buddhist images was a religious practice of immense value. The scripture promises tremendous rewards for the production and receipt of Buddhist images. Moreover, through images, a devotee could even attain nirvana. One of the texts tells us that “a person who makes an image of the Buddha will be reborn into a wealthy family with money and precious jewels. He will always be loved by his parents, siblings, and relatives”.

King Udayana of Vatsa may have commissioned the first sculpture of the Buddha. He ruled in the region of present-day Allahabad, India. According to the story, the Buddha decides to visit his mother in heaven. Moved by the event, king Udayana grieves for his absence.

Then, the king proclaims, “I want to produce an image of the Buddha to venerate and bequeath it to later generations.” Soon, the Buddha’s disciple helps to transport Udayana’s artisans to heaven to copy the Buddha’s form. When the Buddha comes out of heaven, the statue stands to greet him. Later, other kings produced a replica of this statue. The replica of a replica even ended up in Japan.

Although Buddhism has its roots in Hinduism, it has no creator god to explain the origin of the universe. Buddhism also did not have a centrally organized hierarchy, headed by an authority. Instead of having a consistent orthodox doctrine, the community crystallized into a variety of schools that served as a vehicle of Buddhism.

The early form of Buddhism is sometimes disparagingly called Hinayana or the “Lesser Vehicle”. Still, the term “foundational Buddhism” can be used as an alternative to “Hinayana”. At some point, there were about 18 Hinayana schools with diverse doctrines. However, only one of the schools survived into the present. It is known as Theravada or “the Way of the Elders”, and its works are preserved in Pali.

Theravada practice focuses primarily on meditation and concentration. Monastic life is at its center. Adherents believe that this kind of life is a superior way of achieving liberation to the life of a layperson. Theravada stresses the worship of the three “jewels”.

These jewels are the Buddha, the monastic community or sangha, and the Buddhist doctrine or dharma. The highest ideal is that of the arhat. The arhat is a monk who attains enlightenment by following the teachings of the Buddha. Today, Theravada is practiced primarily in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

The newer branch of Buddhism, Mahayana or the “Great Vehicle” appealed more to the masses and, as a result, to Buddhist artists. Mahayanists believe that the doctrine can provide salvation for everyone. During its history, Mahayana Buddhism spread from India to other Asian countries.

For example, China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam have major traditions of Mahayana Buddhism. In this vehicle, the Buddha was deified and became an object of worship. Salvation was possible not through diligent practice but through faith in a pantheon of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

Bodhisattvas had gained enough merit in earlier existences to become Buddhas themselves. However, they postponed entering nirvana to save humankind from the cycle of rebirth and to direct it to enlightenment. In Southeast Asia, bodhisattvas were also associated with the ideology of sacral kingship or devaraja. There, they appear in the guise of Lokeshvara or “Lord of the World”.

In Southeast Asia, there was a kingdom that the Chinese called Funan. At some point, this mighty empire was under Indian influence. However, in about 550 CE, Funan went into a decline. Then, it had two successor states: Cambodia, the kingdom of the Khmer, and Dvaravati, or Thailand. They had developed the cult of the ruler visible in the art.

Due to the close historical and geographical links to southern India, Khmer rulers practiced Hinduism in matters of doctrine and ritual. Still, the borderline between Hinduism and Buddhism was not clearly marked. It fluctuated considerably from one period to another. In addition to Hindu temples, the rulers built Buddhist monasteries and sculptures.

For example, under Yashovarman (reigned c. 925—950), and particularly under Suryavarman I (reigned 1010—1050), a new phase of Khmer Buddhist art began. The Khmer bodhisattvas became more rigid and almost looked like idols.

Nevertheless, these figures keep a sense of humanity. With the death of Jayavarman VII (reigned c. 1181–1218), the old cult of the ruler, associated with Mahayana, and the social structure that supported it, gradually sink into decline. After this period, the Khmer people converted to Theravada Buddhism.

From roughly the sixth to the ninth century, the Mon people ruled Thailand’s central regions. There, Mahayana was influential until the seventh century. Distinct depictions of buddhas and bodhisattvas came with it. Buddha figures of the Mon keep the idealized features and underlying symbolism developed in India. However, ethnic traits of the Mon are present, especially in the facial features.

It seems that the neighboring states influenced the Buddhist art of this region from the beginning. Stylistic influences from Dvaravati, Cambodia in the pre-Angkor period (before 802 CE), as well as the Cham kingdom, present-day Vietnam are clear. Cambodian artistic impact was at its strongest in eastern Thailand.

This standing Buddha was sculpted at a time when artists in Southeast Asia transformed Indian religious and artistic ideas into powerful new forms. It is an example of the early Dvaravati artistic style that developed in Thailand. The close-fitting robe of the figure is without folds. The broad shoulders and the calm, downcast expression also reveal the influences of the Gupta period (from the third century CE to 543 CE) in India. However, the Buddha’s facial features resemble those of central Thailand’s Mon people.

Like Buddhas, bodhisattvas can be identified through various attributes. Usually, bodhisattvas have ornaments, such as high tiaras and rich necklaces. They are carved, gilded, and painted in sumptuous detail. Emblems in their hair can also set them apart.

For example, Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, is recognizable by the seated Buddha Amitabha, his spiritual father, in front of his hairdo. Perhaps, Avalokiteshvara is one of the most popular bodhisattvas, especially in China, where it is called Guanyin. His name means “he who looks upon the world’s cries of distress”.

Avalokiteshvara possesses various magic powers, symbolized in many of his guises. The artist instilled Guanyin of the Southern Sea with humanism. The figure is majestic, yet it also exudes a benign calm and warmth. Consequently, he looks more approachable and emotionally appealing.

This deity is seated in a variation of the pose of royal ease or maharajalila on a base imitating a craggy rock. His right arm is resting on his folded right knee. The left arm touches the rock while the left leg hangs down onto a lotus blossom. The position of the Guanyin conveys the impression that the bodhisattva might at any moment awake from deep contemplation and step down.

Avalokiteshvara also has a special relationship with the people of Tibet. According to the legend, Songtsen Gampo (569–649), a king, introduced Buddhism to Tibet and is believed to be a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara. Moreover, he intervenes in the fate of his people by incarnating as a benevolent rulers and teachers, Dalai Lamas.

Dalai Lama is a title given by the Tibetan people for the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or “Yellow Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism. After his recognition, the fourteenth Dalai Lama became known as Tenzin Gyatso. He is also called “Holy Lord, Gentle Glory, Eloquent, Compassionate, Learned Defender of the Faith, Ocean of Wisdom”.

Samye is the site of a Buddhist monastery in central Tibet. It was probably built between 775 and 779 CE under the patronage of the ruler Trisong Detsen (755 – c. 804 CE) who sought to revitalize Buddhism in the country. The arrangement of the temple represents the Buddhist universe as a three-dimensional mandala or the geometric arrangement of symbols.

The followers of Buddhism shaped another set of practices throughout the centuries. This form is called Vajrayana or the “Diamond Vehicle”. Vajrayana Buddhist art was developed in Tibet, Nepal, Indonesia, the Philippines, China, Korea, and Japan. The diamond stands for indestructibility and the eternal and immutable body of the Buddha. In this form, rituals or sadhana occupied a prominent role for the practitioner.

Through a practice of visualization and petitions, a buddha or bodhisattva can come into the practitioner’s presence. The practices combined elements from both Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. They also added mystical symbolism, magical rites, and ritualistic eroticism. This development is alternately referred to as Tantrism. The word “tantra” means “weave”. Therefore, it can imply the “interweaving of traditions and teachings as threads” into a text, technique, or practice.

Most Tibetan art was created in connection with the complex rituals and meditational practices of Vajrayana Buddhism. The followers employ mandalas or cosmic diagrams as visual depictions of the sacred realms inhabited by a host of deities. In Tibet, thangkas, or painted portable scrolls are commonly used as aids in spiritual enlightenment. They often depict sacred icons or mandalas.

The mandala of the Vajravali Series includes over one hundred and fifty different figures. It was commissioned by the monk Ngorchen Kunga Sangpo (1382–1456), founder of the Ngor monastery, in honor of his late teacher. In this work, each of the four large circles is a mandala in itself, repeating the variation of the same basic structure. Inside the circle, there is a square. The square can be entered through four portals or doorways. Moving through these doorways, closer to the interior of the circle, is the abode of a deity.

Around the four mandalas in the main field is another, floating mandala scheme. It consists of the Five Pancharaksha Goddesses in the four cardinal directions and in the center. They are popular deities for protection against sickness, misfortune, and calamity. 35 small Buddhas of Confession surround these goddesses. Along the top border are 16 seated Buddhas in niches. At the bottom are fifteen Buddhist forms of the World Gods.

Sitting in a dark chapel, lit by candlelight, the practitioner goes into a meditative trance. Then, drawn by the painting, the believer is transported into the heavenly realm. Being in that space, the practitioner is able to absorb the positive energy that the deity transmits.

Buddhist art owes its spread to trade routes across countries. The exchange of ideas went along with the exchange of commodities. Despite many hardships, fearsome merchants traveled across deserts, mountains, and seas. Monks joined caravans, leaving Buddhist artifacts and filling caves with Buddhist art along the trade routes.

Commercial settlements were the first centers of Indian influence, and Buddhist communities were built around them. Their cultural influences spread along the “silk roads”. Along these routes, the oases were not only centers of commerce but also religious centers. They had monasteries that transmitted Buddhist ideas and art to the people of Central and East Asia.

During the third century BCE, with the expanding power of the Indian king Ashoka (reigned c. 268 – c. 232 BCE), Buddhist art burst out of the Ganges Valley and spread in all directions. First, it took root in Gandhara and Kashmir. From there, by the beginning of the first century CE, it was moving through trade routes to China.

At that time, the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) was in power in China, and Confucianism was its state ideology. It praised a benevolent ruler under the Mandate of Heaven. A ruler’s will coincided with that of the people, forming an orderly society with a rigid family structure.

Before the coming of Buddhism, Daoism was a religious tradition of China. Nature governs all life manifesting itself in yin and yang. These negative and positive forces shape all things. It was a philosophy of passivity with avoidance of disagreement.

Furthermore, its ideal was a return to purity for the attainment of eternal life. Neo-Daoists considered inactivity as virtue and non-being as the origin of all things. This seemed to mirror the basic Buddhist idea of emptiness. Thus, Buddhism trickled into this self-contained world of Daoism.

The earliest Chinese Buddhist community appeared in 65 CE. The White Horse Temple in Luoyang, Henan province, was probably the first Chinese Buddhist monastery. Based on the legend, the Buddha appeared as a golden deity in the dream of Emperor Ming (28-75 CE) of the Han. By the middle of the second century, devotees worshipped the Buddha in the palace with Daoist deities.

Nevertheless, Buddhism gained momentum in China only after the collapse of the Han dynasty. Under the invading Turkic and Tibetan tribes, incessant warfare and chaos created ripe conditions for Buddhism. Rulers of non-Chinese origin embraced the new faith to ensure their victory. Therefore, they listened to monks who exerted the restraining influence over killing through the preaching of compassion. Buddhism afforded physical and spiritual refuge to the masses. Furthermore, by becoming monks, common people could escape military and labor services.

In 4th-century China, a few monks laid the foundation of Chinese Buddhism. First, Dao’an (312–385 CE) combined two main currents of Buddhist thought. They were the practice of meditation and the doctrine of emptiness. Later, his disciple, Huiyuan (334–416 CE), likened the indestructibility of the spirit to the endless transmission of fire from wood to wood.

Yet another monk, Daosheng (360–434 CE), argued that all sentient beings have Buddha nature. He believed in sudden and complete enlightenment after a long process of religious training. Therefore, we are capable of becoming a Buddha. This way, Buddhism began to change the Chinese cultural landscape.

Dunhuang was an oasis at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. There, devotees carved cave temples into the hills to serve traveling monks and native believers. Eventually, these Buddhist cave temples became a center of devotion and a depository of Buddhist Art. The Mogao Caves, or the Thousand Buddha Grottoes, form a system of five hundred temples southeast of the center of Dunhuang.

At Dunhuang, the very first cave temple was dug out in 366 CE. Based on the legend, Lezun, a Buddhist monk, stopped to drink at the Great Spring Valley near Dunhuang before continuing his journey. While resting, he watched the sunset over the mountain. A wondrous giant Maitreya, Buddha of the future, surrounded by an aura of golden light, appeared from the mountain.

Lezun was amazed by this vision. He thought that this was the holy place for which he had been searching. Therefore, he abandoned his onward journey to build a cave in this place to pay homage to the Buddha. After cutting his cave from the cliff opposite the mountain, Lezun painted his vision onto the walls of the cave. Then, he added a three-dimensional figure of the Buddha constructed around a wooden frame.

Through Dunhuang, other notable events occurred in the history of Buddhism. For example, in 399 CE, Faxian (337 – c. 422 CE), a Chinese Buddhist monk, started his pilgrimage to India traveling on foot. In a similar fashion, the Indian high monk Kumarajiva (344–413 CE) traveled from Kucha to Chang’an, China in 401 CE. He began his monumental project of translating into Chinese some of the most important Mahayana scriptures.

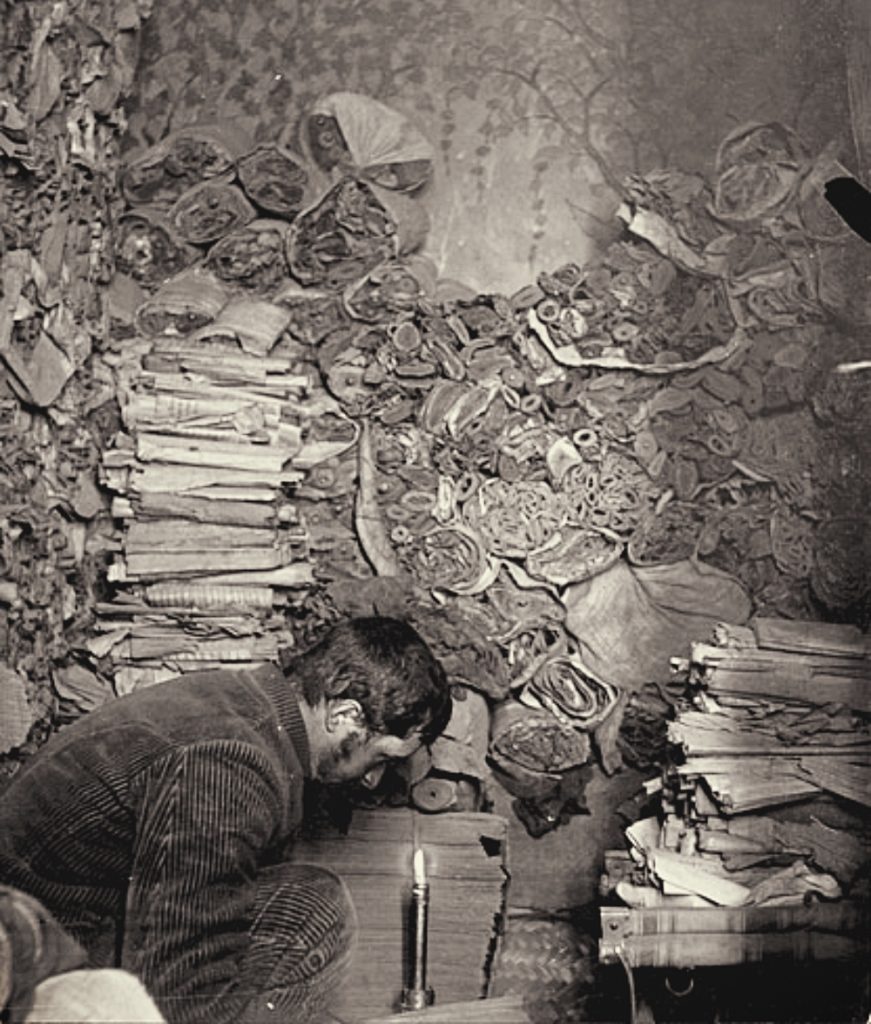

At the turn of the 20th century, Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist priest, discovered a hidden cache of manuscripts at the Dunhuang caves. Many of the manuscripts were Buddhist texts, and other items described everyday life on the Silk Road. Up to 50,000 manuscripts may have been kept there. It was one of the greatest treasure troves of ancient documents found. No one was quite sure why the items were hidden there. However, it was clear that they had been stored untouched for almost one thousand years.

Paul Pelliot (1878-1945), a French sinologist, heard about a find of manuscripts and rushed to Dunhuang. While at making his research, he had written a detailed account of some of the most valuable documents he had encountered. Then, he mailed his findings back to Europe, where it was published upon their arrival. Although he had only a few minutes to examine each manuscript, the sinologist included extensive biographical and textual data. This gigantic effort was so unusual that he was falsely accused of faking the documents.

Throughout the centuries, the popularity of Buddhism in China was growing. The ruling elite realized that Buddhist art can move mountains and change people’s attitudes to a ruler. Therefore, some rulers probably thought that Buddhism could undermine the established Confucian order. In 446 CE, the emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei (408–452 CE) started Buddhist persecution. Consequently, many monks were killed, and a significant part of Buddhist art was destroyed.

However, the succeeding emperor considered himself a reincarnation of the Buddha. In 460 CE, he appointed Tanyao, a monk, to restore Buddhist art. The monk oversaw the construction of the cave temple in Yungang, Shanxi province, China. As a symbol of the permanence of Buddhism, artists created Giant Buddha figures in these caves, representing the past emperors. Additionally, 51,000 sandstone statues of Buddha emerged in 53 grottoes.

Although Buddhist art could move mountains, it was always under the sway of rulers. For example, admiration for Chinese culture motivated the sixth Northern Wei emperor to move his capital to Luoyang. Eventually, the monks occupied one-third of the city’s dwelling area. At nearby Longmen grottoes, craftsmen created cave temples sponsored by the imperial family.

Still, in the north of the country, the emperor Wu (543–578 CE) of the Northern Zhou dynasty had a different vision. Aiming to restore the glory of ancient China, he favored Confucianism. Therefore, he started the second great persecution in 574 CE. The emperor and aristocracy appropriated Buddhist works of art.

Nevertheless, the storm was brief. After the emperor Wen (541–604 CE) of the Sui dynasty came to power, Buddhist art ushered in the golden era. The emperor used Buddhism as a binding influence in the reunification of the north and south of China. His fame attracted envoys from Japan and Korea to seek Buddhist teachings.

Buddhism was introduced to the Korean peninsula from China in the 4th century CE. At first, only the royal courts and the aristocracy supported the religion. However, gradually Buddhism was adopted by all levels of society. By the late 6th century, Korean monks were traveling to China and even to India to receive training.

They returned home with texts and images that played a decisive role in the formation of Korean culture and art. Buddhist art flourished until the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). After this period, Neo-Confucianism became the state ideology. Nevertheless, Buddhism remained a spiritual force in Korean society. Private devotional objects and works for monasteries continued to be made throughout the centuries.

Chinese and Indian Buddhist art influenced Korean artists. However, they have created a distinctive style. One of the most recognizable Buddhist artworks is the sculpture of a pensive bodhisattva. The gilt-bronze image of the pensive bodhisattva with the lotus crown reflects the Chinese styles of Northern Wei (386–534 CE) and Northern Qi (550–577 CE).

This statue has a classic contemplative pose with one leg perched upon the other knee. The fingers of one hand raised against the cheek. The bodhisattva wears a crown with three peaks, a samsangwan. It is also called a lotus crown or yeonhwagwan. The prince wears a simple yet elegant necklace.

This pensive pose is suggestive of the image of Siddhartha contemplating the nature of human life. The chest area is slightly raised. Contrasting with the abstraction of the front, the body narrows at the waist. The artist also made efforts to realistically express the folds of the skirt. Thus, the figure has “spiritual energy,” with a focus on expressing the curves of the body.

After a period of development in China and Korea, Buddhism arrived in Japan. The Korean king of Baekje, a kingdom in southwestern Korea, presented a gilt-bronze image of Buddha to the emperor Kinmei (509–571 CE) of Japan in 552 CE. The Japanese emperor was grateful but cautious at the same time. At first, he allowed only the powerful Soga family to practice the new religion. In fact, many members of the immigrant community in Japan had practiced Buddhism for years before the emperor’s decision.

Buddhism was already one thousand years old when it reached Japan. Therefore, ideas of karma, impermanence, and nirvana were adapted to the needs of the Japanese community. For example, in one of the Japanese sects, nirvana was a place offering personal survival. In Japan, a direct relationship between religion and power formed from the beginning.

In Japan, it seems that people always revered nature. Like in Daoism, nature worship was central to Shintoism, Japan’s native religion. The word “Shinto” means “the way of the gods”. The Japanese believed in the significance of kami or spirits that inhabited awe-inspiring aspects of nature. They developed rituals to express gratitude to nature. Major Japanese Buddhist sects reinforced this practice.

Consequently, Shinto and Buddhism had become associated in the late eighth century. For example, a Buddhist temple could be built next to the Shinto shrine. Buddhist priests took part in major Shinto festivals. Thus, the Japanese embraced disparate beliefs and systems: Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Shinto gods were considered incarnations of various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. For example, Hachiman, the Shinto god of war, became known as the “Great Bodhisattva” that drove off invading Mongols.

By the 7th and 8th centuries, great temples appeared and several sects were functioning in the city of Nara. The emperor Shomu (701–756 CE) ordered the construction of a temple as a charm against smallpox, which ravaged Japan in the preceding years. As a result, Todai-ji, or Eastern Great Temple was opened in 752 CE.

The temple houses Great Buddha Hall, the world’s largest bronze statue of the Buddha Vairochana or Daibutsu in Japanese. He is the deity “belonging to or coming from the sun”. The almost 15-meter-tall seated Buddha consists of 437 tones of bronze. At the time of building, it consumed most of Japan’s bronze production and nearly left the country bankrupt.

After the reign of Shomu, Buddhism became more of personal faith. Throughout the ninth and tenth centuries, many different schools of the Mahayana tradition took hold in Japan. The esoteric Tendai, Shingon, and Pure Land were among the sects. For the followers of Shingon, matter, and mind were not separate, they were the one.

This idea favored the arts as a window into Buddhism. The Buddha’s teaching was without form or color. However, with the help of works of art, we can understand their obscurities. As a result, Amitabha and Avalokiteshvara became the focus of devotional Buddhism. Some of Japan’s greatest contributions to Buddhist art are the wooden sculptural representations of these figures. For example, the serene gilded wood image of the Buddha Amitabha adorns the Byodoin temple near Kyoto.

Amida is the Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Limitless Life. He resides in the Buddhist western paradise or heaven. Until the twelfth century, artists depicted this Buddha seated on a lotus flower waiting for our arrival to the afterlife. However, in later periods, Amida Buddha was often represented in a standing pose. He descends from the heavens to take and transport the devotee back to his blissful paradise.

Amitabha’s right hand is in the gesture symbolizing the Law of the Buddha. The circle of perfection signifies the perfect wisdom of the Buddha and the accomplishment of his vows. The gesture also expresses his great compassion. The thumb corresponds to meditation. Unites with the index finger, which corresponds to air, it denotes the efforts of the Buddha. The act of joining the thumb and the index is symbolic of diligence and reflection.

In the thirteenth century, the two leading sects of Zen Buddhism, Rinzai, and Soto, emerged. These sects belonged to Mahayana Buddhism. They originated in China and were referred to as Chan Buddhism. The common idea was that everyone and everything already have Buddhahood waiting to be discovered. The teaching and practice of Zen Buddhism resonated well with the native Shinto tradition with respect to the love of nature and warrior discipline.

Thus, incorporating native beliefs, Buddhism traveled across countries through images, practices, and stories. Buddhism went across the social structures of the peoples, their codes of behavior, and mythologies. It introduced them to new realms of thought.

Each Buddhist work of art is in one way or another symbolic. Its meaning goes beyond the appearance and immediate purpose. It tries to reveal the dharma for which all images are only provisional signs. The intention of a Buddhist work is to suggest the transcendence of all phenomena and all imagery, a prerequisite for understanding and salvation.

Buddhism spread across Asia as its universal concepts of impermanent existence resonated with diverse cultures. Buddhist art helped communities to experience Buddha’s presence and perpetuate that presence. A jeweled net of Buddhist artworks that artists have left us reflects an unending source of creativity and makes us think.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!