Joséphine de Beauharnais: Patron of the Arts

Joséphine de Beauharnais was born in Martinique as Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. She evolved into the sophisticated and cultured...

Maya M. Tola 20 May 2024

Since the elites in power like the status quo, social reform is a grassroots movement. How do reformers engage the masses? With art. Should protest art show the suffering that needs reform, or the aspiration instead? We look at the Abolitionist movement to see examples of both approaches.

High society in Georgian England (1714-1837) was sumptuous. Such fashion and scenery are reasons the novels of Jane Austen, and TV shows such as Bridgerton are so beloved. Their set-piece words are even fun to say—chatelaines, passementerie, waistcoat fobs, porcelain pieces, Chinoiserie. Yet, the other side of the Georgian economy was terribly ugly and immeasurably cruel. The forced enslavement of people is one of the worst atrocities of history.

Although deemed an illegal trade in 1771, slavery existed in Georgian England. Stories from sailors, travelers, and the formerly enslaved, and news of lawsuits and uprisings, meant the terrible nature of slavery were known in every drawing room.

Pamphlet printed by James Philips, 1787, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Some businessmen could not stay silent. In May 1787, a group of outsider religious businessmen formed the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Since most of these men were not Church of England, they could not directly participate in Parliament. To effect change, they had to speak to the masses. They created an emblem.

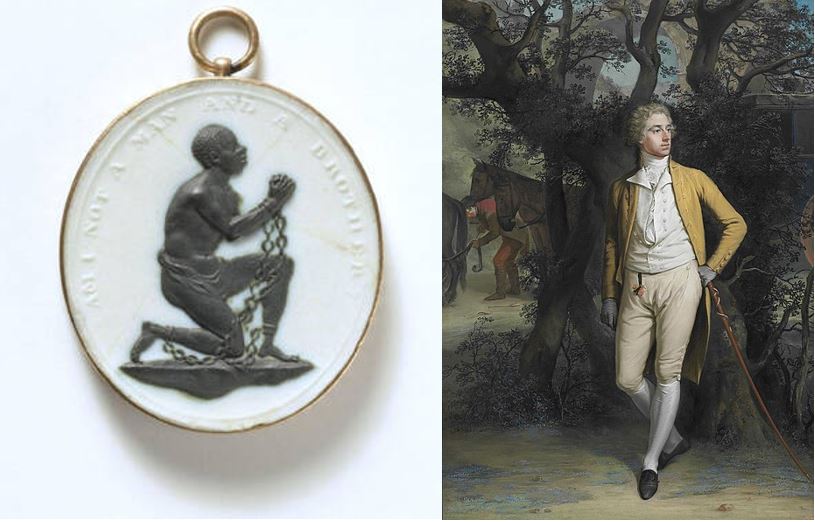

It pictures a kneeling black man under the slogan, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” The Society relied on the Quaker printer, James Phillips, and even met above his shop. Phillips brought about the seal’s creation, although it is not known who actually designed it. Society Tracts with this image were printed by Phillips in the thousands. However, it was another member, Josiah Wedgewood, who ensured the seal really proliferated.

Jaspar trials, with numbers keyed to Wedgwood’s Experiment Book, 1773-1776, Wedgwood Museum – Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent, England, UK. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

20 years earlier, fellow English Quaker Josiah Wedgewood began the process of industrializing pottery production. Among other innovations, he created Jasperware—a matte-finished pottery that got its color not from glaze, but from staining the clay. He also developed kiln techniques that allowed for mass production. The abolitionist idea was hatched for Josiah Wedgewood to cast the Society’s seal into clay and distribute it freely. The little clay coin fast became a Georgian “it” item.

The Wedgewood Medallion in a jewelry setting (left, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK) and a 1785-179 Portrait showing the fashion for wearing charms or medallions on fob-pocket ribbons (right).

The Wedgewood medallion, just 3-4 cm wide, was instantly popular. It was incorporated into the aforementioned sumptuous equipage of high society—watch chains and ribbons, hat pins, jewelry, snuff boxes, porcelainware—all means of ornament were used to wear and display this message of Abolition. But, like society itself, the image was dualistic; is the message decorative or earnest? Is the figure an object of pity or strength? Is he entreating Man or God?

The emblem became the most famous, most proliferated illustration of a black man at the time. It is troubling, through today’s lens, that this would be so of an image that features enslavement and supplication. (See The History of Harlem Renaissance in the USA for a painted example, such as Into Bondage by Aaron Douglas that images self-rescue, rather than a plea to an outside hero.)

In fact, another Abolitionist was troubled by such images and set out to offer an alternative.

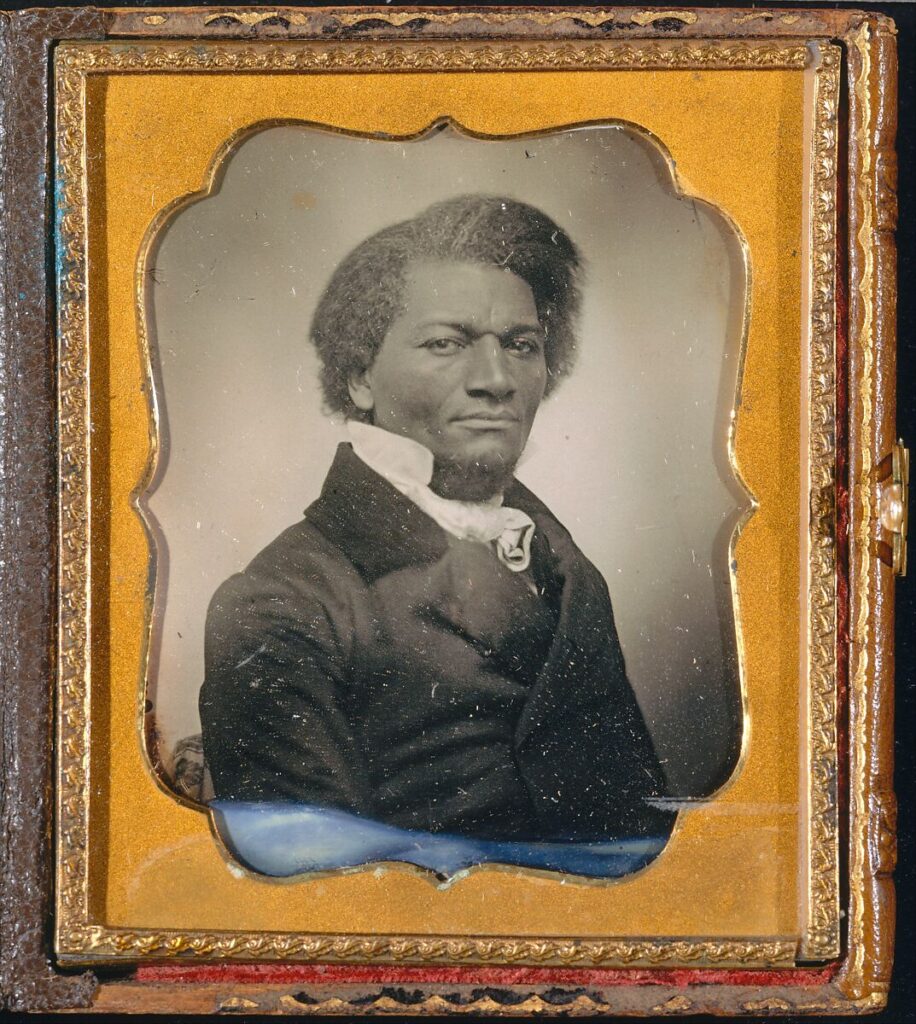

Frederick Douglass, dagguerreotype, c. 1855, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

In September 1838, Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in Maryland, USA. He spent the rest of his life lobbying for Abolition and equality. Douglass didn’t trust artistic representation, where image manipulation by others is possible. He felt the new 19th-century medium of photography allowed him to control his portrayal.

Frederick Douglass took control not only of his image, but also his narrative. Furthermore, like Wedgewood, he understood that his chosen medium facilitated mass distribution.

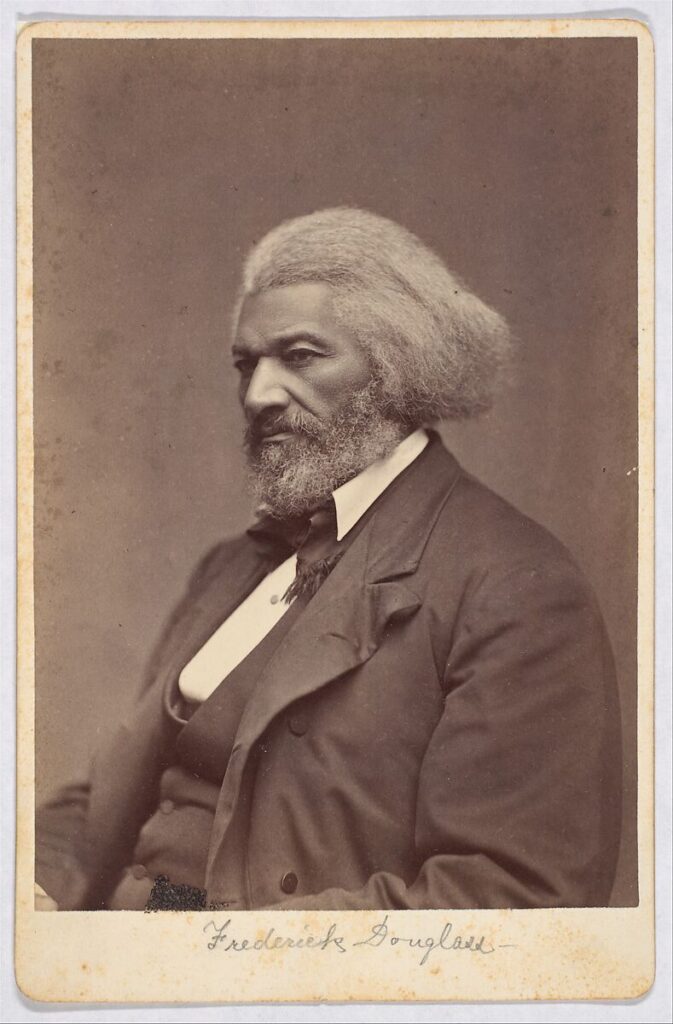

Matthew Brady, Frederick Douglass, c. 1880, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Photos of Frederick Douglass powerfully convey the qualities and attributes that enslaved Black people were denied at the time, and the aspiration for them. It is believed he taught photographers of the day the art of posing, reinventing their subject matter from the outer trappings of people caught under light, to the inner radiance of living and feeling beings.

Douglass distributed his photos freely. He included them in letters and in his widely published books and speeches. He became the most photographed man—from any background—of the 19th century. Always distinguished and well dressed, he self-illustrated promise, dignity, and hope.

Both Douglass and Wedgewood used new art technologies and new techniques of mass production to deliver their protest, and their objects were widely seen. One chose an image of suffering and subjugation. The other chose an image of aspiration and dignity. There is no data letting us know the comparative success to the cause. It is up to each new reformer to decide what and how they immortalize their cause in art and its symbols.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!