Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

Berthe Morisot was an influential painter at the heart of the French Impressionist movement. Ahead of her time, her work was innovative, fresh, and daring. The sheer embodiment of the modern Parisian woman, her work is incredibly well known and popular in France. It’s time for the rest of the world to catch up!

Born in 1841 into a wealthy, high-ranking family, Berthe Morisot was surrounded by culture and always supported by her loving mother, Marie Josephine Cornelie Thomas. Morisot was the epitome of a modern upper-class respectable and sophisticated woman. She was beautiful, but she was also a radical painter.

Berthe Morisot, Self-Portrait, 1885, Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris, France. Museum’s website. Detail.

Middle-class women lived incredibly restricted lives at this point. While her male peers were out in the streets, theatres, cafes, bars, and brothels, Berthe Morisot was essentially a caged bird, living a small domestic life within the confines of her home. Her access to the outside world could only be mediated by her family. However, this challenge, of finding subjects and themes to paint created some of the most stunning images in art history. Morisot captured the informal domestic world of women.

Berthe Morisot, Reading (Portrait of Edma Morisot), 1873, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, USA. Museum’s website.

Morisot’s mother Marie wanted her children to be accomplished in art. She employed tutors of the highest quality to teach her daughters, Berthe and Edma. Let us remember that women were not allowed in art schools at this point. Instead, private tutors and visits to the Louvre (with a chaperone) to sketch past masters were the only options. One particular drawing tutor warned Morisot’s mother that her daughter was so skilled and full of character, that she wouldn’t be painting pretty pictures, but would become an artist, and that this would be catastrophic! Luckily, Marie ignored this and pressed on with her daughters’ education.

Édouard Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

Marie was well-connected, and she sincerely believed in her daughter’s talent. Her support eased Berthe Morisot into friendships and connections with key figures in the French art scene. The most famous of these were the wealthy, liberal Manet brothers. Considered the bridge between Realism and Impressionism, Édouard Manet paints Olympia and The Luncheon on the Grass which scandalized French audiences and changed the face of art. Although art historians have traditionally talked about Manet’s influence on Morisot, in fact, that relationship was one of equals, a two-way communication, where the influence went both ways.

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

Morisot married Eugene, one of the Manet brothers, who was a supportive husband. In fact, Eugene put his own art career on hold to help Morisot forge ahead. Through the 1860s, she was working hard and making contacts. Utterly professional, she wanted to make her mark and sell her art. Morisot exhibited, she sold well, she was in the press, and she was admired by her contemporaries Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre Auguste Renoir. Her work was collected by the French government, evidence that they viewed her as a key painter of the period.

Berthe Morisot, Eugene Manet on the Isle of Wight, 1875, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

Contrary to the white male art history narrative, Morisot was a powerful figure within the Impressionist group, not just a follower – she is the very essence of Impressionism. The Impressionists pioneered an unfinished, unpolished style. Their work was loose, natural, and full of light. Some critics speak of Morisot’s work as delicate and charming, even sweet – unsurprisingly, the male Impressionists weren’t described in that way!

If there is one true Impressionist in this revolutionary group, it is Berthe Morisot. Her paintings have the freshness of improvisation.

Gazette des Beaux-Arts

Berthe Morisot, Summer’s Day, 1878, National Gallery, London, UK. Museum’s website.

Traditionally, a painter would sketch outdoors and then refine the work in the studio. Impressionists believed the work was the process that occurred at the moment, the spontaneous response of the artist to the landscape. The work did not need to be “completed”. Camille Corot taught both Berthe and her sister, Edma, to paint en plein air. Of course for women, this was usually private outdoor spaces such as domestic gardens. If she did work outdoors, Morisot was a curiosity, and her work was often disturbed. For Summer’s Day, a scene of two fashionable women, Morisot posed professional models in a boat in a park close to her home. Morisot had to work from another boat to avoid being harassed.

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle, 1872, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

By the 1870s, Impressionism had placed itself in opposition to official Parisian salon culture. The artists formed their own independent exhibition groups. In 1874, Morisot exhibited The Cradle at the first Impressionist exhibition. The transparent veil over the cradle shows her incredible technique and this single work establishes her as a major talent. And yes, it is a painting about motherhood and maternity – which is what the art world might expect from a female painter. But actually, it is rather ambivalent, and a woman viewing the piece would see that. There is psychological nuance in exploring what it was to be a woman at that time. We see subtle yet complicated expressions of a mental state. Morisot knew very well the dilemma faced by women artists – her exceptionally talented sister Edma gave up her art for her family when she married in 1869.

Berthe Morisot, Portrait of Madame Hubbard, 1874, Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen, Denmark. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Morisot gives us a unique perspective on women’s lives. We look into the modern suburban bourgeois life of women and find not just bored, spoiled housewives, but a modern Madonna. A man could not paint this. He did not have literal or psychological access to that space. Using the power of paint and canvas, Morisot transforms reality, and ordinary objects become extraordinary. She reproduces interiors, furniture, and wallpaper – a real glimpse of social history, these are worlds you can enter and understand, almost 150 years later.

Once she is married, Morisot has the opportunity to paint a man — her husband. She shows him as a domestic father, with his children in the garden, or on holiday, which was very unusual for the time. Morisot also challenges the way male artists depict women. Boudoir scenes were popular, showing women in states of undress, looking out flirtatiously at the (male) viewer. Morisot, however, paints women wearing clothes, in introspective poses. And at a time when portraits of pregnant women tended to be confined to religious Madonnas, Morisot painted her sister Edma, an ordinary, contemporary woman, while pregnant. In the 19th century, women still went into “confinement”, a pregnant bump was not something to be revealed in polite society.

Berthe Morisot, The Mother and Sister of the Artist, 1869–1870, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

It is the poem of a modern woman, imagined and dreamed by a woman.

Berthe Morisot, The Wet Nurse Angele Feeding Julie Manet, 1880, private collection, Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The Wet Nurse, at first a harmonious study of parenthood, is in fact a study of working women. A woman is painting, another woman is feeding her child. Women of Morisot’s class did not breastfeed, this would be anathema to their peers. This is a woman painting her own child, being fed by a working woman. This is about labor – the labor of the woman painter, the labor of the wet nurse. In later works, we watch Morisot’s daughter Julie grow up. The artist captures small, beautiful moments, Julie as a young child, or Julie on the threshold of adolescence.

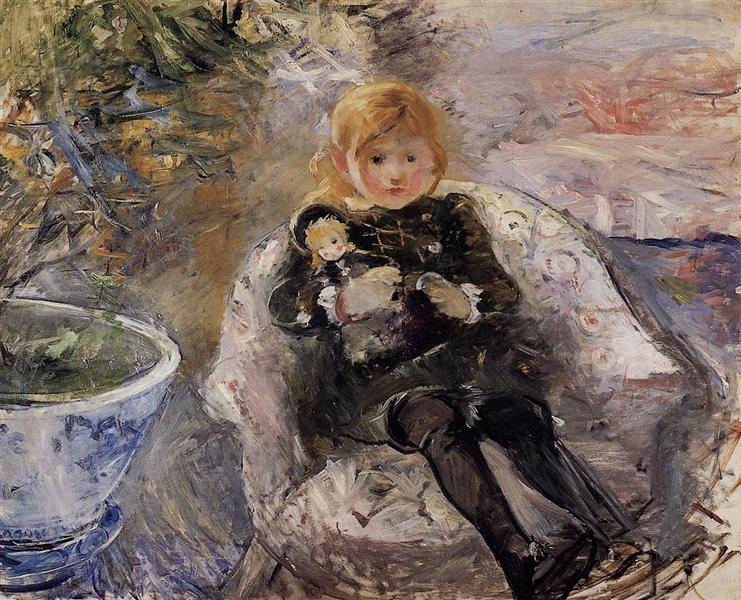

Berthe Morisot, Young Girl With Doll, 1884, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Through the 1880s, Morisot continued to push the boundaries. Her brushwork becomes even looser, her colors more acidic. In Woman At Her Toilette, Morisot leaves parts of the canvas bare, looking unfinished. Here is a woman preparing an acceptable face for the world. Morisot is quite deliberately exploring the limit of painting and representation.

Morisot died quite suddenly in 1895, after nursing her daughter Julie through influenza. She was 54 years old. Who knows where her art would have taken her next?

Berthe Morisot, Julie Daydreaming, 1894, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

How does a woman at the height of her powers, one of the greats of the Impressionist movement, fade into anonymity? In France, she was and is a celebrated household name. Even after the Impressionist era faded, the Parisian avant-garde and the Symbolist poets continued to love and admire her. To their shame, British and American art historians simply ignored her. Samuel Courtauld, a famous and influential arts benefactor, and collector, made a list of key modern art figures he felt should be collected and celebrated – all were men. He left out both Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Morisot was written out of the story. It took feminist art history in the late 1970s for that appalling attitude to be challenged and redressed.

I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, and that’s all I would have asked for – I know I am worth as much as they are.

Artist’s diary entry, in exhibition catalog Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, 2018-2019, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Spring 2023 sees a new exhibition of Morisot’s work at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London. This will be the first in the UK since 1950. The Barnes Foundation held a major Morisot exhibition in the USA in 2018/19. Morisot is finally being placed where she belongs, at the very heart of French Impressionism.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!