Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

Who has not heard of Édouard Manet? The same Manet whose canvas, Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe (or The Luncheon on the Grass), ushered in a new age for art? However, it is interesting that Manet himself was not a revolutionary thinker, nor was he planning to give rise to a new art. In fact, he applied to the prestigious Paris Salon many times and was only accepted by a mere handful. Still, Manet’s persistence, his ability to befriend intellectuals, free-thinkers, and innovative artists, and his talent to live in the moment, made him a memorable figure during his time, and even today. Here are 10 things you may not know about Édouard Manet!

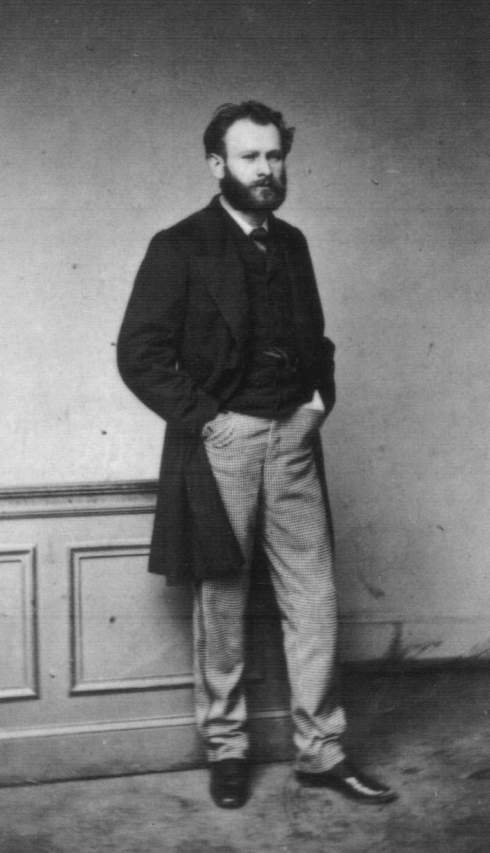

Édouard Manet, c. 1862. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Édouard Manet’s birthplace, Paris, France. Zen Art Supplies.

Édouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832, in his parents’ home. The house stood on the Left Bank of the Seine, in the Fauburg Saint-Germain. Across the street, Manet would find the École des Beaux-Arts, and across the river, the Louvre.

Manet’s parents were very well-connected if not quite aristocrats. His mother, Eugenie-Desiree Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince, Charles Bernadotte. Yes, the same Bernadotte who is the ancestor of the current Swedish royal family. Manet’s father, Auguste Manet, was the chief of personnel in the French Ministry of Justice and very much expected his eldest son to pursue a career in law.

Other notable members of Manet’s family were his two younger brothers, Eugene, who went on to marry Berthe Morisot, and the youngest, Gustave. Manet’s uncle, Charles Fournier, also played an important role in Manet’s life, as he encouraged his artistic pursuits despite Auguste’s opposition. His cousin, Jules Dejouy, later became Manet’s confidante and a legal counselor. Manet even sent his valuables to him for safekeeping during the siege of Paris in 1870.

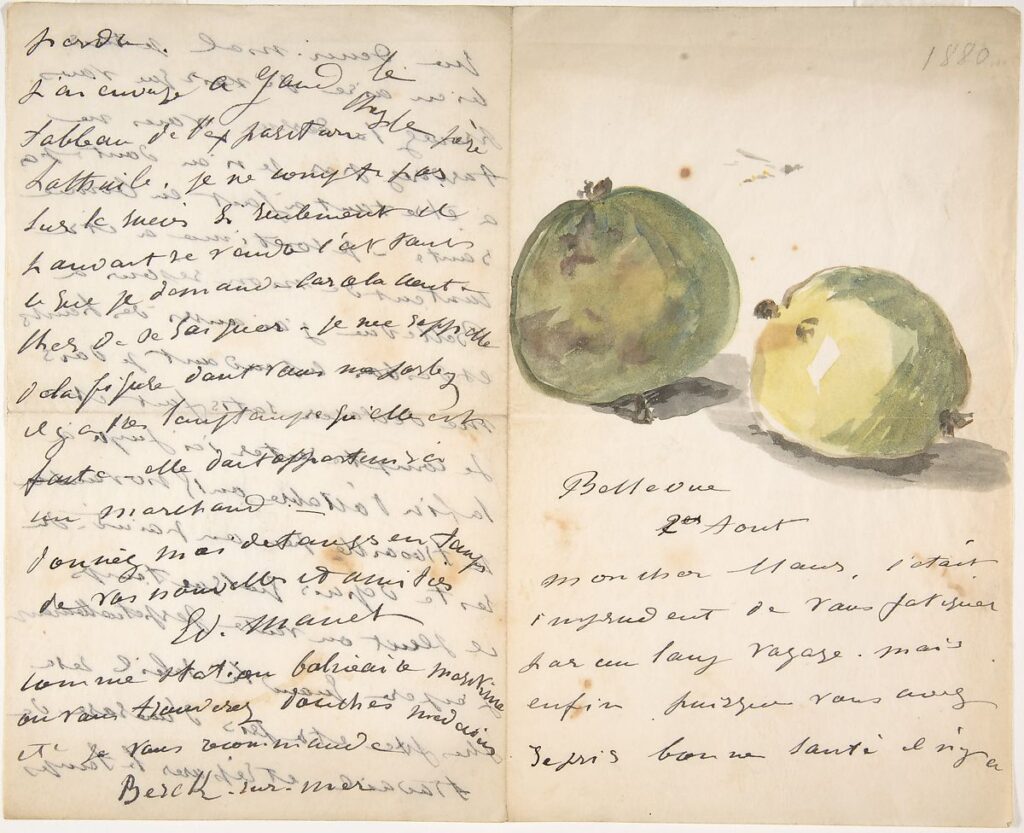

Édouard Manet, A Letter to Eugène Maus, Decorated with Two Apples, 1880, The Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York, NY, USA.

Young Manet had access to a good education. When he was 7 his parents enrolled him at Canon Poiloup’s school, where he studied French and the classics. From 12-16 years of age, he was a student at College Rollin, however, Manet was not a particularly good student. He was opinionated and frequently contradicted his teachers. He became distracted in class and sometimes sketched caricatures of his friends in the margins of his notebooks. His maternal uncle, Captain Charles Fournier, noticed his artistic inclinations and began taking him regularly to the Louvre. He also encouraged Manet to take a drawing class at school, which became his favorite class—perhaps the only class that really interested him in the whole curriculum.

Édouard Manet, Boats at Sea, Sunset,, c. 1868, MuMa, Le Havre, France. Photograph by David Fogel.

There was a conflict between Manet and his father over his future. Auguste Manet wanted his son to follow in his footsteps and study law but Manet could not be persuaded to do so. Since his father would not allow him to become a painter, Manet applied for the naval college but failed the examination. So, in December of 1848, at almost 17 years old, Manet embarked as an apprentice pilot on a transport vessel called Le Havre et Guadeloupe. The trip took Manet to Brazil and lasted about a year. During his time away Manet continued to draw, even making caricatures of the officers and instructors on the ship.

Upon his return to France, Manet took the navy’s entrance exam again, and once again he failed. It was then that his father relented and finally let him study art.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Manet’s Studio in the Batignolles, 1870, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Initially Manet and his father disagreed about where Manet would study. Instead of going to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts to learn traditional painting, Manet opted to study under the tutelage of Thomas Couture.

Couture was a genre and history painter who challenged the École in his own way by setting up his own atelier, hoping to turn out the best history painters. He encouraged his students to pursue their own artistic expression, rather than adhering to the modes of the École.

Manet stayed with Couture for six years, finally leaving in 1856 after an episode in which Manet painted a canvas that Couture disapproved of. When Manet’s fellow students rallied around him, giving him a standing ovation, Couture became furious. After leaving Couture’s atelier, Manet completed his training at the Louvre. He then traveled through Italy, Holland, Germany, and Austria, before finally returning to France to settle and open his own studio with fellow painter Albert de Balleroy.

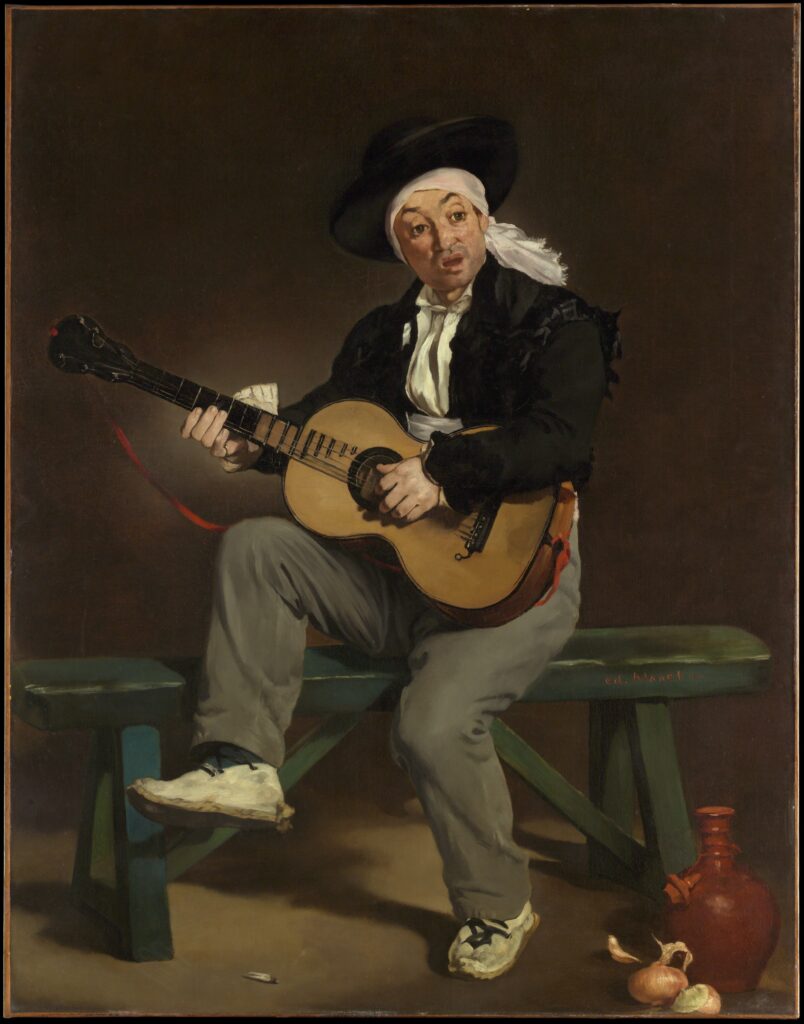

Édouard Manet, The Spanish Singer, 1860, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Manet’s earliest submission to the Paris Salon was The Absinthe Drinker in 1859, but he was rejected. When he was 29, two of his canvases were accepted to the Salon of 1861. These were The Spanish Singer and Portrait of M. and Mme. Auguste Manet. The portrait of Manet’s parents was received very badly by the critics. Meanwhile, The Spanish Singer caught the eye of critic Théophile Gautier, who championed rebels such as Hugo, Delacroix, and Baudelaire. Gautier’s review of The Spanish Singer was enough to ensure its popularity.

Titian, Le Concert Champêtre, 1509, Louvre, Paris, France. Photograph by Dcoetzee via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The sight of Parisians bathing in the Seine reminded Manet of Titian’s Le Concert Champêtre. They inspired him to paint one of the most scandalous paintings in history: Le Bain, or, as it became known, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.

Manet submitted Le Bain to the Salon of 1863 and caused an outrage. Titian’s work also features female nudes with dressed male guests, so it is difficult for the modern viewer to find anything too objectionable with Manet’s offering. What shocked Paris, and the art world at large, was that the male guests were dressed in contemporary attire. This implies that the scene could be taking place in their very own backyards. It was simply too much for the sensibilities of 19th-century Parisians.

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The judges were too harsh that year—the Salon of 1863 refused two-thirds of the paintings presented. That is two-thirds of artists were, in effect, exiled for two years (since the Salon was held biannually) from the most prestigious art scene in Paris. Perhaps, even worse, their artworks would be stamped on the back with a red R, for Refuse, hampering their ability to sell them privately.

The rejected artists complained and boycotted the Salon in such a way that Napoleon III, who did not wish to have more trouble at his door while his government was weakening, allowed for a special salon to be set up to show all the rejected works and let the public judge for themselves. The Salon des Refusés saw more than one thousand visitors a day, marking the first time that so many works were placed together in opposition to the arbiters of art and taste at the École des Beaux-Arts.

Édouard Manet, Interior at Arcachon, 1871, The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, USA.

Leenhoff was an excellent Dutch pianist, hired by Manet’s father in 1851 to teach his three sons. In their early 20s, Manet and Leenhoff developed a romantic relationship that lasted for some 10 years. In 1852, she gave birth to a son whom she named Léon-Édouard Koëlla and introduced in society as her younger brother. Manet never acknowledged Léon’s paternity and there was even some question of whether he could have been Auguste’s son. Whatever the case, Manet lived with Leenhoff secretly after leaving his father’s house. They later married in 1863, after Auguste’s death.

Manet was very fond of Léon and his domestic life, taking him out on walks through the Batignolles each Thursday and Sunday. Leenhoff and Léon posed for a good number of Manet’s canvases. Most famously, Léon is the subject of Boy Carrying a Sword of 1861.

Édouard Manet, Civil War, 1871-1873, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

After the French forces of Napoleon III were crushed at the Battle of Sedan in September of 1870, the Prussian armies advanced toward Paris. Rather than staging an invasion, the Prussians began a siege that lasted almost a year. Manet sent his family out of Paris but remained behind as a staff lieutenant in the National Guard. In his letters to Suzanne, he mentions illness, despair, and hopelessness as the days turned into weeks and months and people began to eat horses, mules, and even their own pets.

Édouard Manet, The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil, 1874, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

It seems Manet was a very charismatic figure. His friends described him as witty, sociable, humorous, bold, and independent, which made him a natural leader among younger artists. Somehow he was always surrounded by interesting, curious, forward-thinking people. While he was still at College Rollin, Manet met and befriended Antonin Proust, who became a lifelong friend, journalist, and politician. Later in life, Manet met and befriended luminaries such as Charles Baudelaire, Eugène Delacroix, Émile Zola, Edgar Degas, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet (with whom, at first, there was a little bit of animosity), among so many others. He even counted Englishman Alfred Sisley and American James Abbott McNeill Whistler among his circle of friends.

Another friend of Manet’s, the poet Théodore de Banville, wrote this verse in his honor:

The laughing, blond Manet,

Emanating grace,

Gay, subtle and charming,

With the beard of an Apollo,

Had from head to toe,

The appearance of a gentleman.

The Italian artist Giuseppe De Nittis, a young friend, said of Manet:

No one has ever been kinder, more courageous, or more dependable.

Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, The Courtauld Gallery, London, UK.

While he opened up a studio in 1856, Manet’s public career properly began in 1861, the year of his first participation at the Salon, until his death in 1883. In 1975, Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein cataloged his known, extant works: 430 oil paintings, 89 pastels, and more than 400 works on paper.

Manet cannot be properly called an Impressionist because he never exhibited in any of the Impressionist Salons. Furthermore, his artistic and stylistic preoccupations were not in line with the Impressionistic pursuit of the effects of open-air light and immediacy. However, Manet’s boldness and vision opened a door for Impressionism to come through and to change the world.

Manet’s Grave at Passy, Paris, France. Photograph by Martin Ottman via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

In April of 1883, Manet’s left foot was amputated because of gangrene, due to complications from syphilis and rheumatism. He died 11 days later and is buried in the Passy Cemetery.

Manet’s last major work is A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, from 1882. Just a couple of months before his death he was still painting vibrant, colorful, exquisite flowers. It is fitting that such an exuberant, charismatic, larger-than-life figure made art continuously, leaving for us such life-affirming works right until the very end.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!