Kettle’s Yard: A Tour Through Cambridge’s Modern Art Gallery

Kettle’s Yard, a somewhat modest home in the middle of Cambridge, UK, harbors an impressive art collection of predominantly modern and abstract...

Ruxi Rusu 24 June 2024

The Cleveland Museum of Art is a major American art museum, renowned for the quality and breadth of its collection. It includes more than 61,000 works of art ranging over 6,000 years, from ancient to contemporary pieces. Its story began with a group of civic leaders in Cleveland who wanted to build a museum “for the benefit of all people forever”.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is located in the U.S. state of Ohio. The city of Cleveland was established on July 22nd, 1796. In the 1800s the process of industrialization gained momentum. Soon, machines replaced human labor in manufacturing, increasing the production capacity of industry tremendously. A new nationwide network of railways distributed goods far and wide.

In this changing landscape, people focused more on business activity. Progress in the arts lagged behind business and industry. However, as businesses prospered, some families began to assemble private art collections. Yet Cleveland’s wealthy did not have a museum to show works of art to their fellow townsmen.

In 1873 a financial crisis triggered an economic depression. Many people lost jobs, homes, and all their savings. Even the mayor of Cleveland offered to cut his salary in response. Because of the continuing depression, some high-society Cleveland women hit upon the idea of promoting a loan exhibition of art objects. These cultured Clevelanders emptied their houses for the occasion. The resulting exposition was put on in an old high-school building downtown.

After their successful beginning, this group of citizens organized another exhibition. It aimed to raise funds for the victims of another depression known as the Panic of 1893. The catalog for the Loan Exhibition of 1894 revealed the steady growth of art collections in private homes of wealthy families. By this time the idea of a Cleveland Museum of Art was in the air.

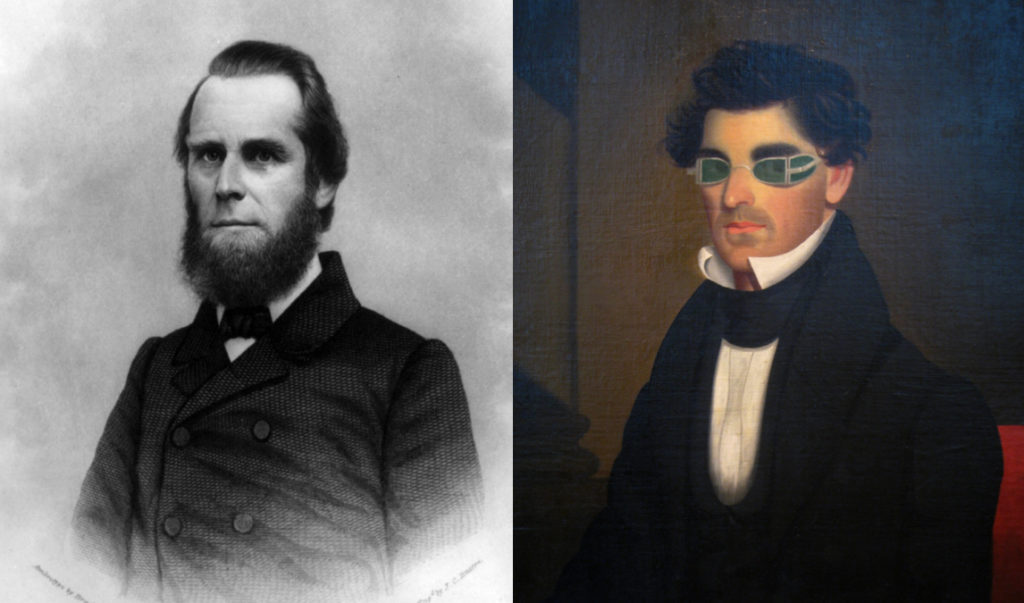

Jeptha Homer Wade I (1811-1890) was an industrialist and one of the founding members of the “Western Union Telegraph”. He was a kind of a “Renaissance Man” staying at the forefront of developments in art and technology. Before turning his interest to the telegraph, he was a portrait painter and photographer, making portraits and daguerreotypes. The daguerreotype was the first publicly available photographic process in the 1840s and 1850s.

Wade moved to Cleveland with his family in 1856. He used his vast wealth to benefit the city. In 1882, he donated land to the city of Cleveland for the purpose of creating a park. Named in his honor, Wade Park is Cleveland’s Cultural Center. Now it is surrounded by the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Western Reserve Historical Society, and the Cleveland Botanical Garden.

Like his grandfather, Jeptha Homer Wade II (1857-1926), was also a successful industrialist. He served as an executive in 45 companies including railways, mining companies, manufacturing firms, and banking institutions. He was also a philanthropist and a generous supporter of the Cleveland Art School and the Protestant Orphan Asylum.

Following the Wades’ example many other Clevelanders became active philanthropists. They helped to turn the dream of building the Cleveland Museum of Art into a reality. One of these charitable donors was John P. Huntington. He was born in a small cotton milling town in Lancashire, England, in 1832. After taking part in a strike of textile workers, Huntington could not get employment in his hometown. Therefore, he brought his family to Cleveland.

Huntington started as a laborer but soon he had built his own business producing asphalt. By 1867 he was a member of a firm which engaged in refining oil. Later, Rockefeller absorbed Huntington’s enterprise into Standard Oil. Due to his business acumen and hard work, John Huntington became one of the wealthiest men in Cleveland. An active participant in the municipal affairs of Cleveland, Huntington served as a councilman of Cleveland for 13 years. During this period he helped to create a paid fire department and city sewer system, to deepen the Cuyahoga River channel, and to construct the Superior Viaduct.

Along with John P. Huntington, two other prominent industrialists, Horace Kelley and Hinman B. Hurlbut, developed their interest in art on their trips to Europe and soon started to collect art objects. By 1891 it became known that the three businessmen had been bequeathed substantial sums for an art museum in Cleveland.

However, the progress in carrying out the wishes of the donors slowed down. For example, there was considerable public discussion about the best location for the proposed museum. Things started to take shape when Jeptha Homer Wade II gave the land on which the Museum stands as a Christmas gift to the city. Sharing his grandfather’s interest in art, he was one of the founders of the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1913. Wade served as its first vice-president, and later became president in 1920.

The Cleveland Museum of Art first opened its doors to the public in 1916. It was one of the largest construction projects in Cleveland at that time. Enthusiastic visitors filled the museum space. The opening exhibition, which ran from June 7th to September 20th, 1916, attracted 191,547 visitors. The attendance at the Museum for the first full year exceeded 376,000.

Landscaped gardens surround the Cleveland Museum of Art, which overlooks the Wade Park Lagoon. The building of white Georgian marble and distinguished Neo-Classical design, contained a rotunda, foyers, galleries, an auditorium, lecture rooms, and a garden court among other facilities.

Originally the court had cages with birds and a pool stocked with goldfish. There was a piece of pavement from a villa of the Caesars, furniture from Pompeii, columns from a Roman temple, Greek and Italian objects, and a Chinese marble Buddha of the sixth century who “sat peacefully amid these classical surroundings”.

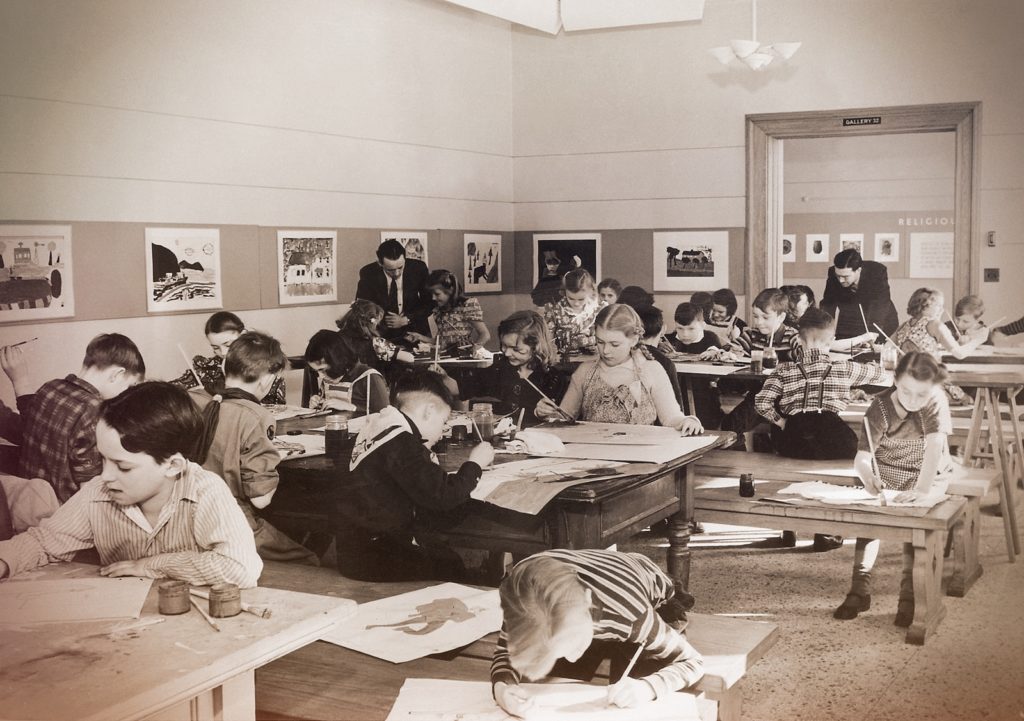

Frederic Allen Whiting was the museum’s first director from 1913 to 1930. He did not have any formal training in art education or art history. Hence he approached the problems of the Cleveland Museum of Art from the point of view of a social worker. Whiting considered museums to be “community schools for the soul”. For him, museums were laboratories for the development of art appreciation, not simply mausoleums in which to store buried treasures.

The director also hoped that textiles would inspire modern designers. He sought to develop the aesthetic consciousness of manufacturers and workmen through the Cleveland Museum of Art. In time, exhibitions would hopefully stimulate the public to demand more beautiful merchandise. Also while the worker would have greater pride in his craftsmanship.

In the 1920s, the Cleveland Museum of Art also had a tapestry among its art objects. Time is one of three silk and wool masterpieces dating from the late Gothic period in the 1500s. It shows the picturesque quality of life in the lush French countryside, stressing the pleasures of youth and the sorrows of age.

A tapestry is a heavy, handwoven pictorial design. Tapestries served as murals to cover walls in residences, churches, and palaces. The tapestry Time has shallow space, unnatural scale, and stylized figures. Due to its subtle modeling of drapery folds, the tapestry could pass as a painting. While the intricacy displayed in the tapestry’s natural forms is a testimony of medieval artisans’ interest in humans’ association with nature, it also illustrates their great skill in creating space and linear movements in the weaving process.

The creation of a pattern or illustration was the first task in the production of a tapestry. The weavers then took over the next stage by completing the image in thread on a loom. Weavers had to be both technicians and artists to capture the subtleties created by the image’s designer. Peter Paul Rubens created illustrations for tapestries in the seventeenth century. In the twentieth century, Picasso, Miró, and Matisse worked on similar commissions.

William Mathewson Milliken was the director of the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1930 to 1958. Before becoming the director he organized the museum’s first May Show. It later became a juried exhibition for regional artists annually held at the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1919 to 1993. The director was an expert showman and promoter of both the exhibition and the works of individual artists.

He had to steer a middle course between those who want to stay with the traditional forms of representational art and those who would fill the museum space with the latest creations. Milliken believed that the role of the museum was not to endorse all it shows in its galleries, but to acquaint the public with new developments in the field of art. The public could decide what it regarded as ephemeral and what was likely to endure.

The Museum stayed on the cutting edge of modernism, exhibiting impressionists, post-impressionists, futurists, cubists, etc. These included such artists as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Gino Severini, and Georges Braque. At the beginning of the 20th century one of the “radicals” in art was Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881-1973) a Spanish painter, sculptor, print-maker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet, and playwright. He is best known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, and the co-invention of collage.

Art historians divide Picasso’s works into periods marked by changes in style. In this painting Harlequin with Violin of the “Synthetic Cubism” period (1912–1919), the diamond-patterned costume and triangular hat identify the musician as one of Picasso’s alter egos. This was a Harlequin, a jokester from the popular Commedia dell’arte, which was an early form of professional theater. It originated in Italy and was popular in Europe from the 16th to the 18th centuries. The phrase “si tu veux” on the sheet of music may refer to a popular song that begins “If you wish, Marguerite, make me happy by giving me your heart.”

Whatever the ultimate verdict, this kind of exhibition helped make art a subject of popular interest and discussion. Art became fashionable and as a result the public gradually became more used to new experiments with color and form.

As if tuning into a harlequin with a violin, Cleveland’s was among the first art museums in the country to turn its attention to performing arts. It started to offer music programs as part of its regularly scheduled activities. The Museum gave a series of both free and ticketed concerts by local and internationally known musicians in the museum’s Gartner Auditorium. This was part of the Education Wing built in 1971. It also contains two large special exhibition galleries, classrooms, lecture halls, and an audiovisual center.

The Cleveland Museum of Art also showcases dance. Take a look at the impressive Hindu masterpiece Shiva Nataraja, Lord of the Dance which shows Shiva, one of the most enigmatic Gods of the Hindu Trinity. He represents creativity and at the same time symbolizes the myth of Death and Life.

The story begins with the Shiva who has been asleep for millions of years. He awakens, shakes the drum in his right hand, and begins to dance. The dance causes the universe to come into being. After eons of dancing, Shiva destroys the universe with the fire in his left hand. He returns to sleep and the universe perishes until he awakens again.

This story represents an important Hindu conception of how change and creativity occur. Shiva is dynamic, vital, and energetic. His hand pointing to the foot shows that the dance represents life. The fourth hand is a benediction assuring us that all is well and that death and life, or change and creativity, are the stuff of our existence. The ever-changing postures in the arms and legs, with each succeeding silhouette providing a new figure, is similar to time-lapse photography.

World War II took Sherman Emery Lee to the Far East with the armed forces as an adviser on art collections. He later served as the officer in charge of the arts and monuments division of American General Headquarters in Tokyo. After he left his position as associate director of the art museum in Seattle, Sherman Lee became a curator of Oriental art in the Cleveland Museum of Art and later the director of the Museum (1958-1983).

He had to deal with some of the most notorious episodes in the museum’s history. Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), a French sculptor, created his masterpiece The Thinker in 1880-1881. The figure was intended to represent Italian poet Dante pondering The Divine Comedy. A cast of this statue is located outside the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 1970, a group of political radicals destroyed the statue’s base and lower legs. After the incident, the director decided not to have the statue repaired or recast or put in storage but to remount it in its damaged state outside of the museum.

As director, Sherman Lee put a strong emphasis on encouraging the scholarly standards of the work. The Cleveland Museum of Art has a diverse art collection, educational programs, and publications. This is because of the directors who applied and will continue to apply their vision and strengths in the development of the museum. The public opinion and fate of artworks is in the hands of the directors.

A village pastor was one of the guests who visited the museum for the first time in his life. He was so shocked by the nudes that he likened the Cleveland Museum of Art to a ‘House of Shame’. The pastor thought that it could lead people (especially children) to vice and ruin. He demanded a purge of all nudes from the Museum’s galleries. However, the director informed the minister that “the body is God’s temple” and “nothing is good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

In his painting The Judgment of Paris in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Joachim Anthoniszoon Wtewael (1566-1638), a Dutch Mannerist painter and draughtsman, depicted the Trojan prince Paris who also had to make a judgment but of another matter. This classical painting is full of motion and reveals how Paris chose beauty. The prince was asked to determine which goddess was the most beautiful. Hera offered him political power, and Athena, military prowess, but Paris awarded the golden apple to Venus, the goddess of love, who promised him Helen, the most beautiful mortal in the world.

If you are looking for beauty, the free of charge exhibition Tiffany in Bloom (20 October 2019 – 14 June 2020), organized in the Cleveland Museum of Art, is one of the Must-See Art Exhibitions in 2020. It combines well-thought-out design, artistic excellence, and technical prowess.

At the turn of the 20th century, not only did people brighten their houses with art pieces, they also started to use electric table lamps. Incandescent light bulbs had become more widely available in the 1890s. However, most households did not have electricity at that time. Tiffany lamps originally had an oil-burning apparatus, consisting of a reservoir and a double wick and chimney, as well as an electric attachment.

Clara Wolcott Driscoll (1861-1944), the head of the Tiffany Studios Women’s Glass Cutting Department in New York, designed the Peacock Table Lamp. She created more than thirty Tiffany lamps produced by Tiffany Studios, among them the Wisteria, Dragonfly, Peony, and from all accounts her first — the Daffodil.

Most of Tiffany’s shades and bases were meant to be interchangeable. The main feature of this lamp is the peacock feather, depicted in stained glass in the shade and in bronze and inlaid glass pieces on the base. When looking at this shade in the round or from overhead, it looks like a preening male peacock with outstretched feathers. With the help of an animated recreation, visitors can look at the inside to see the many different varieties of Tiffany’s glass that produce the striking color, texture, and contrast of the design.

To create a 3-D model the designers used photogrammetry, a series of overlapping photographs, capturing every part of the object several times. Then, the images were uploaded into a 3-D software program. After a series of processing steps it produces the 3-D model from photographs.

The growing art collection demanded an addition to the original museum building. As a result the museum’s floor space doubled in 1958. A second expansion took place in 1971 with the opening of the North Wing. Its angular lines stand in distinct contrast with the flourishes of the 1916 building’s neoclassical facade. The museum’s main entrance was shifted to the North Wing. The auditorium, classrooms, and lecture halls were also moved into the North Wing. This allowed their spaces in the original building to be renovated into gallery space.

In 1983 an additional West Wing was added to provide a larger library space as well as nine new galleries. However, between 2001 and 2012, the 1958 and 1983 additions were demolished. In their place a new wrap-around building, East, and West Wings were constructed.

A new structure was also built along the south side of the 1971 addition. It allowed the Cleveland Museum of Art to integrate the new East and West Wings with the building to the north. This created extensive new gallery spaces on two levels, as well as providing room for a museum store and other amenities. From 2005 until 2014, renovations and expansions enlarged the museum. The new East and West Wings rose under a soaring glass of canopy.

In the 21st century, digital technology helps museums transform the experience of viewing art. The Cleveland Museum of Art has ARTLENS Gallery. It has a series of interactive displays and a mobile phone app that allow visitors to view and interact with the museum’s digitized collection.

With this app you can create your own digital artwork, zoom in on works of art, and connect with the museum’s world-class collection. You can also save the artworks you learn about and photos you take during your experience and then map your visit throughout one of the top art museums.

A huge number of artworks in the permanent collection (about 30,000!) are available in open access online. With your imagination you can be a “Picasso”. Download open access images and combine them into a collage. Mix images with the help of the ArtLens Studio application. Use images to showcase your idea or even a business. Research, combine, and develop – the only limit is your imagination.

The ARTLENS project in the Cleveland Museum of Art is a delight for many people. It can help them to develop a better appreciation and judgment of art. This satisfying experience with the art world can add to the enjoyment of life and enrich their sense of value on the whole human enterprise.

The history of the Cleveland Museum of Art represents an achievement in combining material wealth, creative energy, and a desire to develop and enrich visitors’ artistic tastes. It is a place of enjoyment, discovery, enlightenment, knowledge, and understanding. Here art comes to life through the lens of technology. Exhibitions connect people, epochs, ideas, and accomplishments.

Check out the Cleveland Museum of Art website and explore its amazing collection of art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!