The Greatest Male Nudes in Art History

Nudity started being an important subject in art in ancient Greece. The male body was celebrated at sports competitions or religious festivals, it...

Anuradha Sroha 19 November 2025

From Kylie to the Kardashians, bums seem to be big news. But that’s not just modern selfie culture: the female body, especially buttocks, have been a symbol of fertility and beauty since early human history, and this is perfectly mirrored in art.

Modern women face a daily barrage of hopelessly unattainable images of womanhood. Ever more scary surgical procedures are advertised. Get a Brazilian Butt Lift on your lunch hour—sepsis and stinky necrosis available with every purchase! It’s good to remember that womanly bodies come in all shapes and sizes, so let’s take a moment to celebrate that cellulite.

The Venus of Willendorf has exaggerated buttocks, hips, and thighs. Made of oolitic limestone, she is just over 11 cm (4 in.) tall and can be held in the hand. She is over 25,000 years old from the Paleolithic Period. Academics suspect she is a goddess/deity figure—a symbol of well-nourished fertility.

Venus of Willendorf, c. 29,500 BCE, Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgement of Paris, c. 1632–1636, National Gallery, London, UK.

Peter Paul Rubens is, of course, the undisputed master of the fleshy bottom. In The Judgement of Paris we see a kind of beauty contest between Venus, Juno, and Minerva, the prize being the golden apple in Paris’ hand. In the painting, Paris is a Trojan prince, disguised as a shepherd. Ordered to compete before a mere mortal, these large, fleshy goddesses look confidently in command of their bodies and their sexuality.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, 1630–1635, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Three equally confident beauties appear in Rubens’s The Three Graces. This skillful signature style became known as “Rubenesque,” a term used for portrayals of realistic, sensual flesh. Rubens didn’t stick to the rigid female archetypes of so many male artists, and the playful, plump, dappled derrieres of his women are a joy to behold.

Peter Paul Rubens, Venus in Front of the Mirror, c. 1614–1615, Gartenpalais Liechtenstein, Vienna, Austria.

Rubens painted Venus in Front of the Mirror around 1614, an image re-visited by Diego Velázquez some 30 odd years later. Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus is more slender than the rounded Rubens, with darker hair, and without adornment. It is quite a departure from the classical depictions found in other works.

Diego Velazquez, The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus), 1647–1651, National Gallery, London, UK.

The Rokeby Venus is the only surviving nude by Velázquez. Nudes were rare in 17th century art—remember the Spanish Inquisition was policing the art scene! This painting is famous for being attacked by Suffragette Mary Richardson in 1914, although it was later fully restored. She said she didn’t like “the way men visitors gaped at it all day long.” Well, she did have a point!

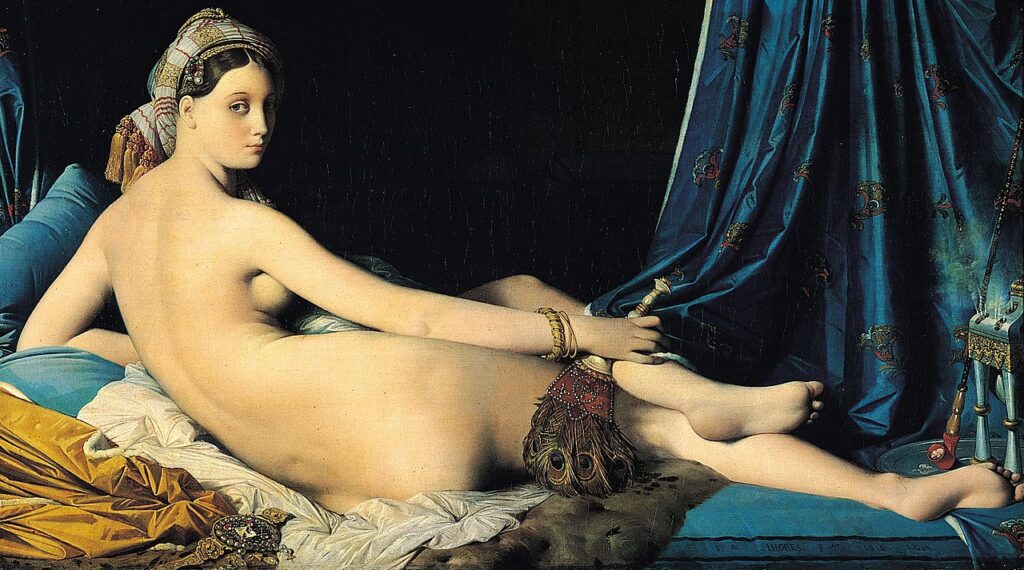

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Louvre, Paris, France.

An image that drew strong criticism from the public and art critics alike was La Grande Odalisque, the most famous nude by painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in 1814. The long, sinuous lines of this woman bear little resemblance to anatomical reality, a distortion derided by contemporary critics. Now it is hailed as the first great nude of the modern tradition.

Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1900–1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Moving even further away from traditional representations of the nude figure in painting, Paul Cézanne produced a whole series of bathers paintings from the 1870s onward. His The Large Bathers is considered one of his finest works and was an inspiration for the Cubist movement. However, it appears that Cézanne was not comfortable around naked models, and so his bathers were inspired by classical paintings and his own imagination.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Nymphaeum, 1878, Haggin Museum, Stockton, CA, USA.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau stayed with the grand manners of the past when he orchestrated a whole host of frolicking nymphs in his painting Nymphaeum in 1878. These are not really flesh-and-blood women—they are visions of perfection. They have impossibly smooth skins and perfectly proportioned bodies, but I have included them here, just for the sheer number of bottoms! Is this innocent and charming or creepily erotic? What do you think?

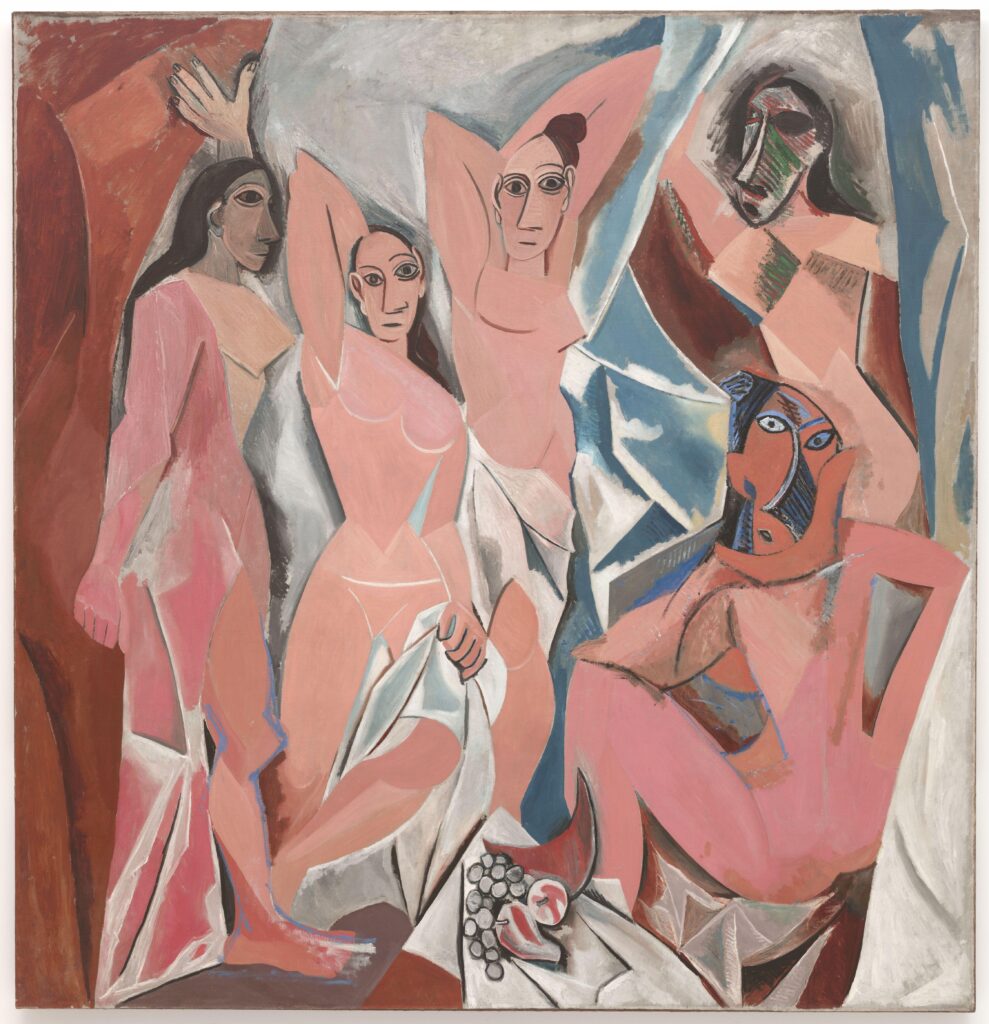

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Pablo Picasso was the first to deconstruct the butt with Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon. See how the graceful curves of Rubens have become sharp and jagged. These women seem dangerous rather than welcoming, but from what we know about Picasso’s life now, we could say that we are dealing with a predatory man here. Picasso was no feminist!

Laura Knight, Self-Portrait (The Model), 1913, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. ArtUK.

Laura Knight painted this image at a point in history when women were denied access to life models. The painting was shunned by the art world (how dare a woman paint a naked woman!). This work, from 1913, was a direct and rebellious response to such absurd rules. Have you heard of the “male gaze”? It is a theory from writer and academic Laura Mulvey, that art presents the bodies of women as objects of desire for the gratification of men. With Laura Knight, the female gaze finally asserts itself!

Lavinia Fontana, Mars and Venus, c. 1595, Fundación Casa de Alba, Madrid, Spain.

Another woman who was ready to be brutally honest was Lavinia Fontana. In her 1595 painting Mars and Venus, it’s pretty clear that Venus is not at all happy with the wandering hand of Mars. Check out his gratuitous bum squeeze. Is she countering with pursed lips and a withering look, or is she just charmed at his audacity! What do you think?

Dorothea Tanning, Nue Couchée, 1969–1970, Tate, London, UK.

In the 20th century, it seems we fell out of love with flesh. Or at least with the infinite varieties of the glorious feminine form. Women seem to be judged on the merits of particular body parts, not as a whole. The media sells us contradictory directions. Big boobs are in, but not saggy ones. Bubble butts are in, but take a couple of ribs out to emphasize that tiny waist. Look fruitful and fertile, but don’t ever reveal a post-birth baby belly.

Here’s an idea! What if we check back in with our cultural heritage? Accept the bodies around us. Don’t drool over surgical or AI generated butts. Gaze at the women on the walls in our galleries. Get inspired by instagram accounts like @museumbums. It’s time to rebel, to draw in some body positivity. Butts can be ALL shapes and sizes. Go on, Rubens would be proud of you!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!