The Greatest Male Nudes in Art History (NSFW!)

Nudity started being an important subject in art in ancient Greece. The male body was celebrated at sports competitions or religious festivals, it...

Anuradha Sroha 19 November 2024

Hidden underground for hundreds of years, depictions of sex, love, and erotica in Andean pre-Columbian art are now proudly displayed in the Erotic Gallery at Museo Larco in Lima, Peru. The exhibition, available for visit online, offers up a fresh (yet ancient) worldview of a topic now still often considered taboo amongst many parts of our society: the human body, and its role in sex for pleasure, as well as reproduction.

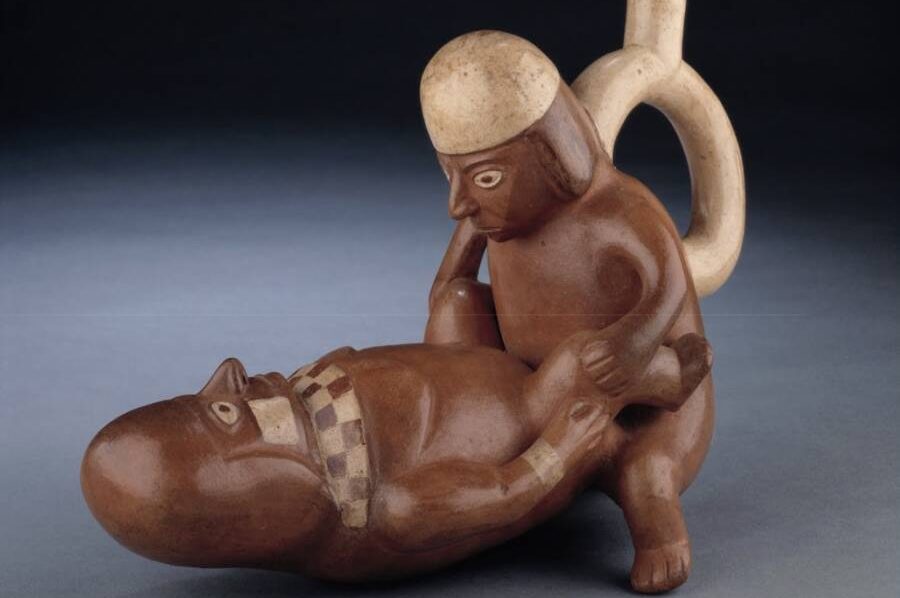

Moche sexual union, Moche culture, Florescent Epoch (1 CE–800 CE), Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Museum’s website.

In 1992, Madonna brought the often hidden world of sex and erotica to the eyes of the public through her acclaimed book, Sex. “Sex is not love. Love is not sex. But the best of both worlds is created when they come together”, she wrote on the first page. And while this candidness in talking about it certainly was shocking to the Western world, it was hardly new for humanity. In fact, sex has been a part of art and myth alike for thousands of years.

It is through that lens that in 1966, Peruvian archeologist Rafael Larco published Checan: Essay on Erotic Elements in Peruvian Art. Checán, in the traditional muchik language, means love and was chosen by Larco to describe what he saw as a universal truth shown through sexual interaction.

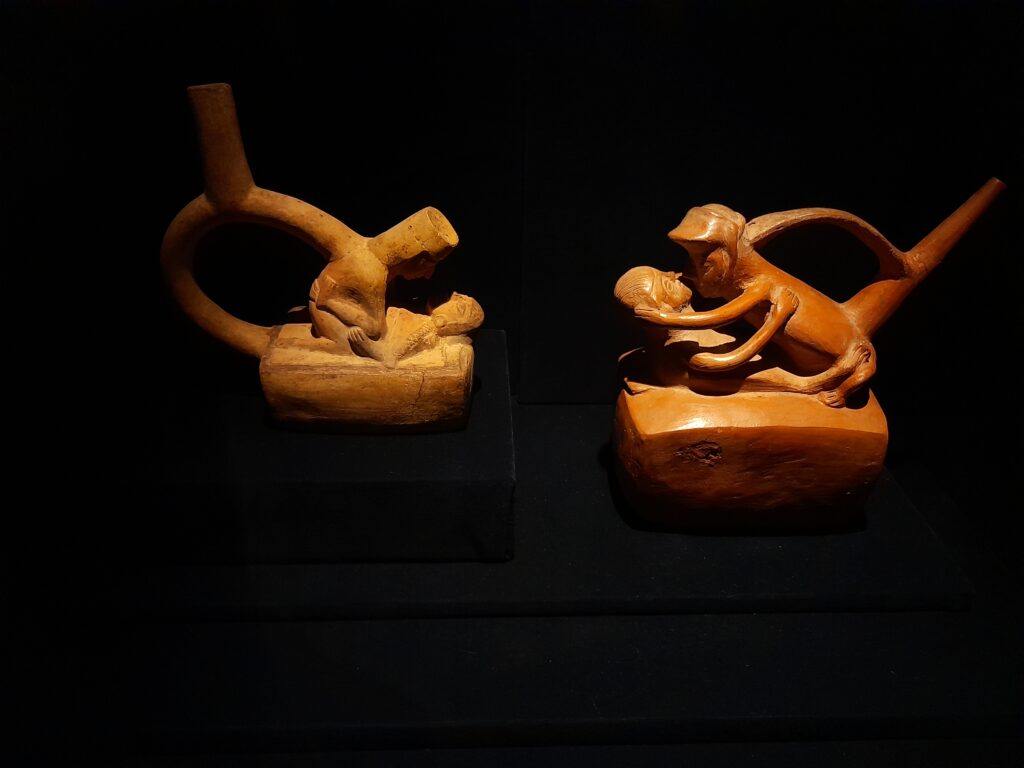

Clay figurines, Vicus culture, Peru, 1250 BCE–1 CE, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

This is the subject of the permanent exhibition at the Erotic Gallery in the Museo Larco, in Lima, Peru. Through hundreds of pottery pieces, which range in pieces from approximately 1250 BCE to 1300 CE, the human body is presented as a vessel for reproduction, regeneration, and communion with the gods, all through the act of love and pleasure. The pottery pieces themselves, described as made out of clay and water, shaped by knowledgeable hand, hardened by fire, and cooled by the air, invite erotic stimulation. This is not only because of what’s represented on them, but because of how they are handled, and even made.

Bottles depicting the female body, Salinar culture, Peru, 1250 BCE–1 CE, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

Very common amongst the Mochica artifacts, phallic-shaped vessels were used to drink liquids during sacred ceremonies. By design, the drinking itself had to be done through the ceramic penis, or else the liquid would spill. But what would probably invite giggles nowadays wasn’t anything to joke about for the Mochicas.

Pottery bottles shaped like male genitalia, Vicus culture (1250 BCE–1 CE), Moche culture (1 CE–800 CE), and Lambayeque culture (800 CE–1300 CE) Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

The Mochicas inhabited northern Peru from about 100 to 700 CE and had influence over almost a third of the country’s length today. They lived by the sea and were agriculturally based. Like most cultures around the world, they were very observant of seasons and reproduction cycles, which they represented in parallels to the human body and sex. Nowadays, the naked body is often hidden from the viewer in an act of shame or modesty. The pottery of the ancient Mochicas, however, shows knowledge of it, gained through study and observation, and also integration into the day-to-day activities, suggesting a very different attitude towards it.

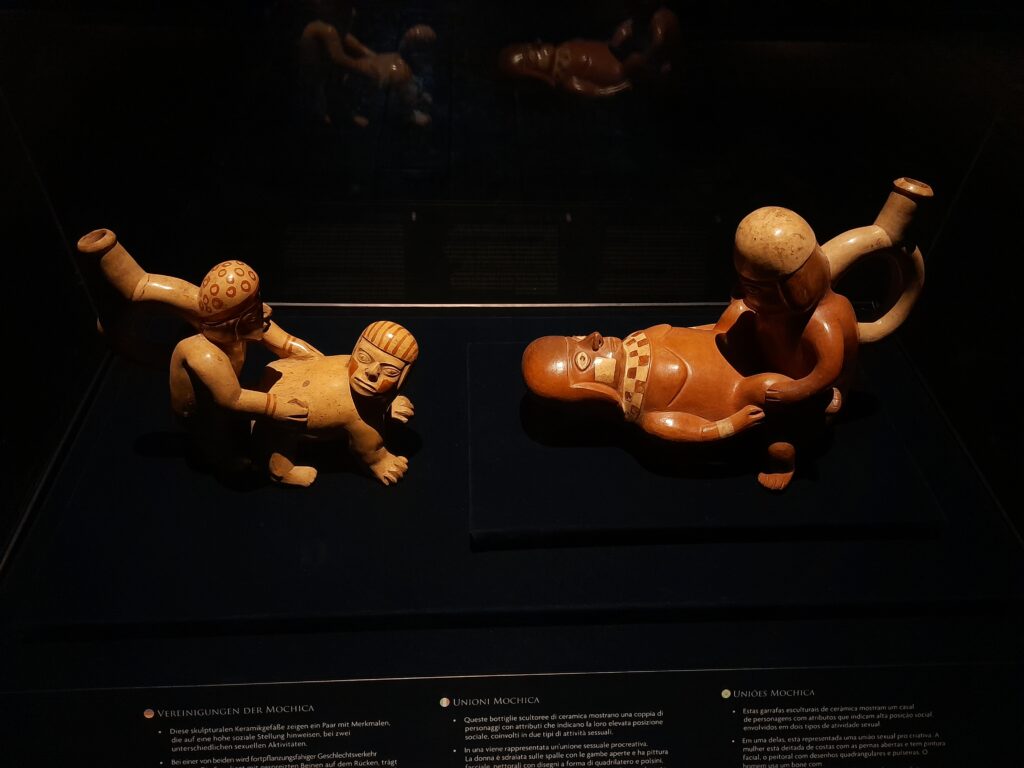

Scultural clay bottles depicting intercourse between a high ranking couple, Moche culture, 1 CE–800 CE, Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

As depicted on the pottery in the gallery, the Mochicas recognized sexuality and eroticism, an inextricable link to the animating vital forces of the world, such as the natural power to create life. This characteristic was extended to the Pachamama (earth), as a mother to every living being above. According to some myths, it had been Ai Aiapaec, a civilization hero, who fertilized her with his semen, after enduring challenges to prove his worthiness. This meeting of complementary forces is often referred to as Tinkuy. Such as day has to encounter night, and then day again, men and women had to come together to engender new life.

Pottery depicting the union of Ai Aiapaec and a woman, Moche culture, 1 CE–800 CE, Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

This aspect of sex as a ritual, rather than a reproductive goal, is depicted in many forms. For example, depictions of oral sex, either on men or women, suggest it may have been ceremonially practiced as a tribute to mother earth.

Intercourse itself was shown in very creative ways, ranging from anthropomorphized genitals interacting by themselves to humans in different sexual positions. Whether engaging in an attempt at reproduction, or as means of pleasure, the inhabitants of old Peru sculpted many scenes from their sexual activities, each one unique.

Anthropormorphic penises, Moche culture, 1 CE–800 CE, Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

Elements like face painting, special clothes, or geometric patterns, tell us of the importance attributed to the practice of sex. Even the position of the handles, connecting the heart to the sexual organs, was meant as a way of indicating the spiritual aspect of sex.

Keeping in theme with the reproductive aspect of sex, scenes like childbirth or breastfeeding were also pictured in the sculpted pottery. Breastfeeding, a rite from which not even the gods were exempted in myth, has been pictured in art all over the world. And the Mochicas were no exception.

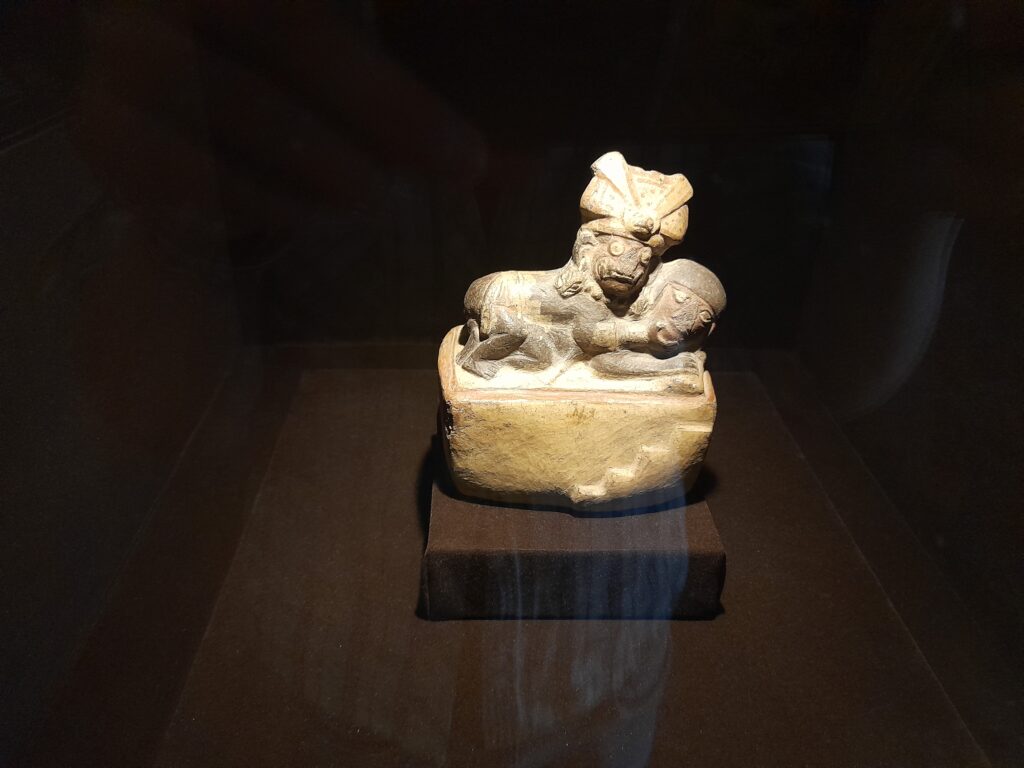

Other scenes presented animals and their mating habits. While some are simply depictions of nature, other times they represent an aspect of myth. For example, toads, which represent the humid world and are akin to the female womb, mate with the earthly jaguar to give birth to a jaguar-eared toad, from which the cassava plant grows.

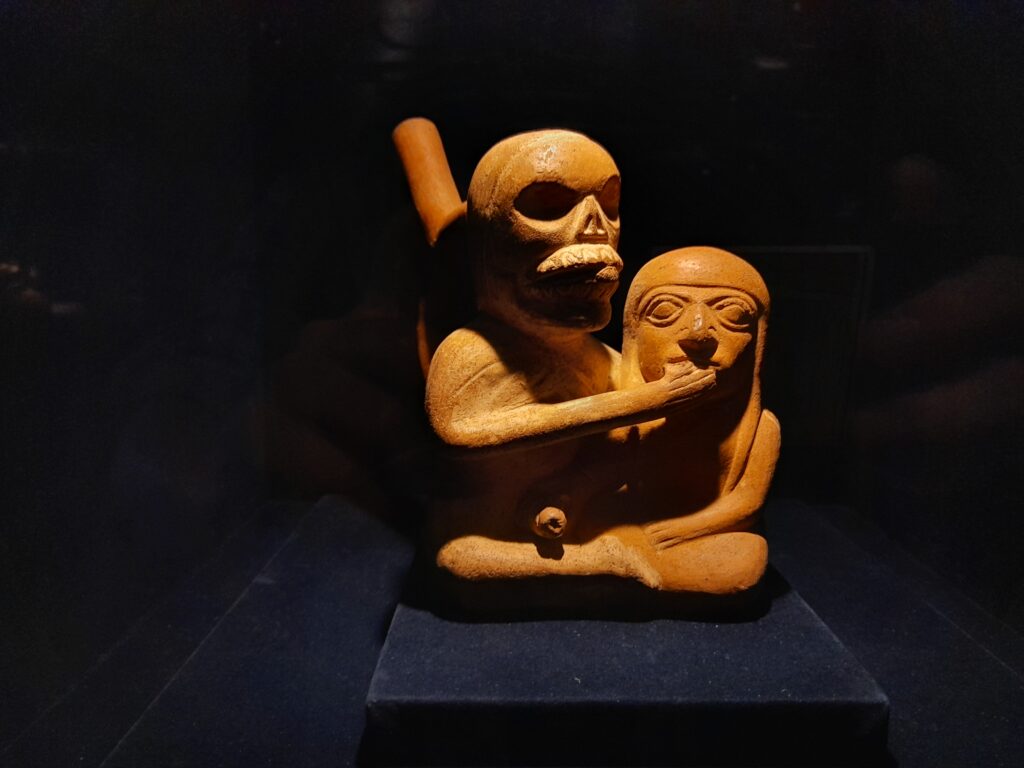

And while sex was indeed regarded as a life-bringing rite, it wasn’t limited to the living. According to the Moche worldview, the dead ancestors were in charge of revitalizing the earth by having intercourse with it from the inside. As evidenced by the pottery, different non-reproductive sexual activities (oral intercourse and masturbation) were likely practiced in ceremonies linked to agricultural fertility. Other times, when divinities attempted to go into the underworld, and the dead awoke and visited the world of the living, anal intercourse had to be practiced because the natural order of the world had been inverted.

Pottery showing an ancestor engaging in sexual activity in the underworld, Moche culture, 1 CE–800 CE, Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

While the Erotic Gallery’s exhibition features a tomb, where many of these pottery pieces were first found in the beginning, it is only fitting to talk about it at the end. Ancient Peruvian pottery, through which much of the Andean pre-Columbian history has been reconstructed and understood, has been found buried and hidden in tombs, long forgotten by their survivors (if there still are any). Cultures like the Mochica, Chancay, Nazca, Incas, and many more, left mysteries that will never be solved, but they also left much evidence to help us piece together how they saw the world. Exhibitions such as this help us remember that whatever truth we behold from our own experiences, reality, and world views can be a unique experience depending on who’s telling the story.

As Rafael Larco himself is quoted in the exhibition (from his book Checán):

[…] as I bring to a close this book on one of the aspects of Peruvian archaeology for which, as a reference, we have only erotic vessels, I leave readers free to arrive at their own conclusions.

Checán, p. 128.

Sculpted pottery depicting intercourse between man and woman, Moche culture (1 CE–800 CE), Lambayeque (800 BE–1300 CE), Peru, Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. Photo by author.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!