Athena in Art: The Beautiful Warrior Goddess

Athena, the revered Greek goddess of wisdom, war and the arts, has captivated the imagination of artists for centuries. Her image, from ancient...

Jimena Aullet 15 August 2024

8 March 2023 min Read

Long ago in the city of Corinth in Ancient Greece, a young maid traced the contour of her lover’s face on the wall. The man was leaving on a long trip. So, she figured out a way to preserve his image. With the help of a lamp, she cast the shadow of his profile and used it as a guide. And that is how the painting was born. At least this is the story Pliny the Elder told in his famous work Natural History. Of course, this is just a myth. However, it still appeals to audiences. For once, it attributes the invention to a woman popularly called Dibutades or the Maid of Corinth. Furthermore, it became a popular theme among Western artists from the 1770s to the 1820s.

The origin of things has always fascinated people. In ancient times, they appealed to myths to explain it. The painting was not an exception. Different cultures from all around the world offered their own stories. One thing they share is that painting started with someone outlining another person’s shadow. For example, there are Tibetan and Mongolian legends that associate this idea with Buddha’s image; as well as Indian myths.

In Western culture, one of the most important writers of Antiquity offered his version of the story. Pliny the Elder (23/24 – 79 BCE) dedicated a whole book of his Natural History to discuss the arts. Firstly, he addressed the origin of painting.

“The claim of the Egyptians to have discovered the art 6000 years before it reached Greece is obviously an idle boast, while among the Greeks some say that it was first discovered at Sikyon, others at Corinth. All, however, agree that painting began with the outlining of a man’s shadow; this was the first stage, in the second a single color was employed, and after the discovery of more elaborate methods this style, which is still in vogue, received the name of monochrome.”

Pliny the Elder, from the Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art.

In this canvas, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo placed a cartouche with an inscription in Latin that translates as, “The beauty that you admire in renowned painting originated in shadow.”

As we can see, Pliny the Elder did not offer any name or concrete story regarding the discovery. He admitted that various cultures claimed the deed without certainty as to who did it first. Then why do people talk about Dibutades? For her story, we have to go beyond this chapter.

Indeed, it’s not until we read the chapter on clay modeling that we finally meet the lovers. As he was tracing the origins of clay modeling, Pliny the Elder mentioned the famous Corinthian maid. He did not name the woman, but her father was a potter called Butades. As a result, she commonly appears as Dibutades.

“She was in love with a youth, and when he was leaving the country, she traced the outline of the shadow which his face cast on the wall by lamplight. Her father filled in the outline with clay and made a model; this he dried and baked with the rest of his pottery, and we hear that it was preserved in the temple of the Nymphs until Mummius overthrew Corinth.”

Pliny the Elder, from the Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art.

Throughout history, several personalities continued spreading the myth. Leonardo Da Vinci, Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, and Giorgio Vasari, all referred to the story in their writings. Some of them included Dibutades and others only mentioned a man’s shadow cast on the wall. From the 17th century onwards, her popularity rose among Western artists. It is curious though, that they manipulated the account to fit just the painting. They tend to leave Butades’ invention of clay modeling to the side, even though he was the focus of Pliny the Elder’s discussion.

Dibutades’ story has always been present. There are numerous examples of Medieval manuscripts where her name stands out. However few illustrations exist before the 17th century. Despite this, by the 1770s the basic features of the scene were mostly defined. There are a few elements that make the iconography of the Maid of Corinth: a classical setting and the two lovers.

For instance, in 1675, the German art historian Joachim von Sandrart (also known as the “German Vasari”), published his famous Teutsche Academie, or the German Academy of the Noble Arts of Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting. In this book, he included an engraving of the myth.

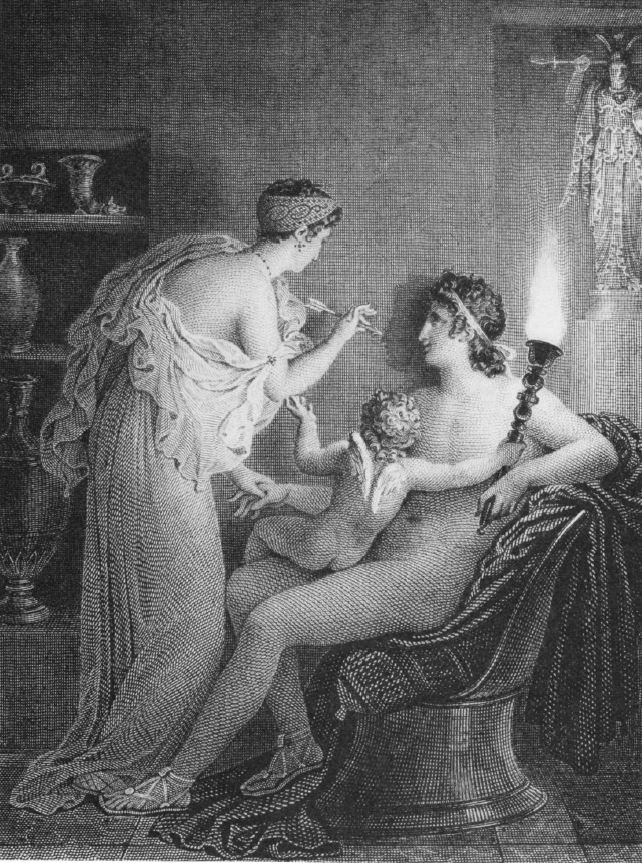

However, in a later version, we find another recurrent element: Cupid guiding Dibutades’ hand. This addition emphasizes the idea that painting was born out of love. He also added a few pottery pieces to remind us of Butades, even though he is absent.

Although Pliny stated a lamp as the source of light, painters took artistic freedom in this element. For example, Alexander Runciman (1736-1785) depicted a nocturnal scene, a choice that reminds us of the future Romantic style. Furthermore, he added the inscription: “With love the master, behold the Greek inventress.” Others, take the scene to broad daylight, as we will see later or they change from a lamp to a candle.

More illustrations of the myth appear here and there. Nonetheless, we can find Dibutades more prominently in writings and poems.

Dibutades’ fame reached its peak from 1770 to 1820, especially in Britain and France. Perhaps the reason was the multiple editions and translations of Pliny the Elder’s works in the 18th century. Additionally, it appeared in Diderot’s Encyclopedia, as well as in a translation of Apologetics by Athenagoras. All of these works serve as a source of inspiration.

David Allan (1744-1796) depicted the story for the Academy of St. Luke in Rome. Following Pliny the Elder’s account, he returned to the indoor setting of Butades’ studio and the oil lamp. He enjoyed great success, both in Rome and at home. It was engraved several times and George Thomas included it in his Select Collection of Original Irish Airs for the Voice United to Characteristic English Poetry Written for the Piano Forte, Violin, and Violoncello, Composed by Beethoven.

“Thy ship must sail, my Henry dear, / Fast comes the day, too soon, too sure, / And I, for one long tedious year, / Must learn thy absence to endure. / Come let me by my pencil’s aid / Arrest thy image ere it flies; / And like the fond Corinthian maid, / Thus win from Art what Fate denies”

William Smyth, from Robert Rosemblum, The Origin of Painting: A Problem in the Iconography of Romantic Classicism, 1957.

Another curious example is the one commissioned by Josiah Wedgwood. It was produced by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797). Wedgwood was a potter, hence his interest in the story. However, in Wright’s painting, the focus remains on Dibutades, not on her father. Yet, it is clear they are in his studio. Moreover, his main source could have been Apologetics because that was where the young man appears sleeping.

Furthermore, this Dibutades is accompanied by Penelope on another canvas, also Wright’s creation. It seems like the late-18th century British enjoyed the theme of the faithful woman who awaits her lover. In fact, in both works Fido represents loyalty. Additionally, Wright was a master of tenebrism. Therefore, the dark environments suited his style perfectly.

We cannot talk about Dibutades without mentioning Jean-Baptiste Regnault’s painting. He made it in 1785 for none other than queen Marie Antoinette. In this case, he decided to move the scene to broad daylight. It certainly reminded the audience of the Rococo period of French art. He also transferred the lovers into a sort of Arcadia and made them a couple of shepherds.

Just as with Wright’s Dibutades, Regnault’s one is not alone. On this occasion, she is partnered with Pygmalion and Galatea. These stories form a circle, seeing that one turns a person into an artwork, while the other transforms an artwork into a living human being. Here we can see how the drawing serves as a substitute for the lover. It’s not merely a likeness, his essence lives in it.

A must-see example of this story is The Origin of Painting by Joseph Benoît Suvée (1734-1807). This painting was not only well-received, but it also earned a place at the Paris Salon of 1791. Suvée returned to the indoor, dark setting that the British loved. In his case, the young lover is fully awake and quite focused on the maid. Moreover, there is an erotic element as he can’t keep his hands off her.

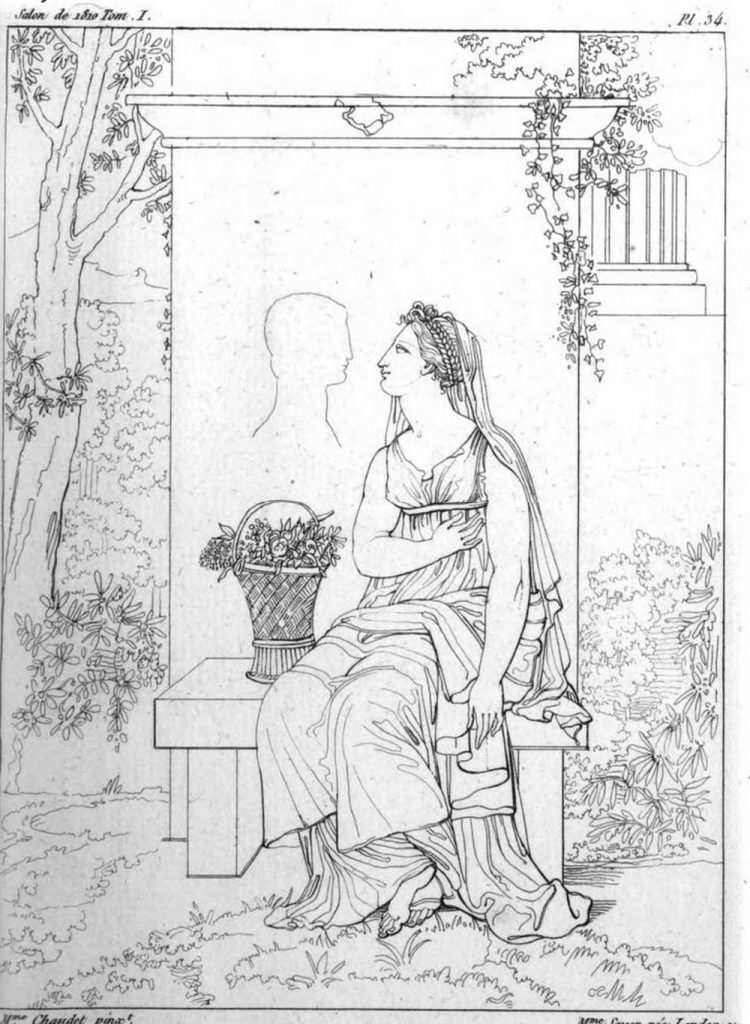

Suvée’s rendition of the theme was not the only one that got a place at the Salon. For a story that awards a woman with this invention, we have only talked about male artists. But female painters also depicted Dibutades on their canvases. In 1793, Mlle. Gueret exhibited her Modern Dibutade. Later, Jeane-Elisabeth Chaudet (1767-1832) got her chance in 1810.

It was originally titled Dibutade Coming to Visit Her Lover’s Tomb and Lay Flowers There. Chaudet was famous for her sentimental works and her depiction of Dibutades is no exception. Unlike the rest of the examples, Chaudet shows us a moment when the young lover has gone already. Dibutades then goes on to contemplate the silhouette. Furthermore, she added a basket of carnations to symbolize pure love.

Unfortunately, both works are gone. Gueret’s work is lost while Chaudet’s was destroyed during World War I. It used to be at the Arras Museum in France.

From the 1820s onwards, Dibutades’ fame faded but it never disappeared completely. Her story keeps resonating even today as she appears in many discussions on female artists.

Not only that but it has also been used for political purposes. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union imposed socialist realism (not to be confused with social realism). The idea was to portray overly idealized, academic scenes about life in the USSR. But not everyone agreed with it. In response, Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b. 1945) created a series of canvases to parody and make fun of the government.

It is a constant question in feminism, where are the women in art history? Unfortunately, art, like every other aspect of human life is submitted to patriarchism. For centuries, women have had to overcome huge obstacles to become great painters, and sadly a lot of them went unnoticed or were erased from history. That is why Dibutades’ story continues to appeal to audiences. And it certainly raises a sort of pride in women today.

Lastly, a movie excerpt from Robin Hood by Enid Bennett & Douglas Fairbanks from 1922 featured a scene that reenacts Dibutades’ story.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!