Art on Screen: 12 Movies About Artists Worth Seeing

Whether troubled or exciting, extraordinary or perfectly average, the lives of artists are an endless source of inspiration for cinematographers.

Edoardo Cesarino 18 September 2025

For Disney’s acolytes, spotting hidden references that link different movies brings more excitement and joy than unwrapping presents. But what if the fan is also an art lover? Well, the knowledgeable Disney animators have that covered. Join us in this real art hunt!

“Narrator: Long ago, in the faraway land of ancient Greece there was a golden age of powerful gods, extraordinary heroes and greatest and strongest of all these heroes was the mighty Hercules. But what is the measure of a true hero? Now, that is what our story…

Muse I: Will you listen to him? He’s making the story sound like some Greek tragedy! Lighten up, dude!

Muse II: We’ll take it from here, darling.

Narrator: You go, girls…”

– ‘Long Ago’, Hercules, 1997, Walt Disney Pictures.

Now, I am no ancient Muse, but I will try to tell you about Hercules and Venus de Milo all the same! Hercules debuted in 1997, at the end of what is culturally known as Disney’s Renaissance. It did alright on Rotten Tomatoes, but received unexcited reviews due to the style of the drawings. Very pointy elbows and swirling ears that look like cinnamon rolls, just to mention a couple of anatomical details. Although one might not fancy the aesthetics, the inspiration that the animators drew from real ancient Greece’s pottery is worthy of the art lover’s appreciation!

So, Hercules embarks on a mission to be granted access to Mount Olympus, home to all Gods. Crucially, he is also rather goofy and clumsy. While he hangs with Meg (Megara – the movie’s leading female character) in an idyllic garden, Hercules skips stones to keep himself occupied, as the embarrassment between the two grows. This is when, by mistake, he knocks both arms off of one of the statues, turning that Venus into the limbless, classic beauty we know today.

Behold the very art reference of this list: Venus de Milo! This ultra-famous statue was found on the isle of Milo (Greece) in 1820. Albeit, we still don’t know exactly by whom. Different sources identify the discoverer with different names. At least they all agreed it was a Venus – the Roman equivalent of the Greek Aphrodite. Also, the finding’s location is uncertain. It was a cave in one version, a partially buried building in ruins in another. Thankfully, the year is certain and matching in each historical source. Something else we don’t know is how Venus lost her arms. However, another congruence between the sources is that the statue was brought back to light already missing them. Given the uncertainty, it could have been Hercules’ doing after all…

After losing several valuable pieces looted around Europe by Napoleon, past his fall from power, the Louvre Museum intensely campaigned to establish Venus de Milo as an outstandingly beautiful find. The operation was supported by many eminent scholars and artists. Although, there is a record of Pierre-Auguste Renoir referring to it as a military-looking figure, a gendarme. Nevertheless, in time the campaign revealed to be a rather successful one. This Venus is a very iconic statue, featured in all sorts of contemporary art pieces, reproduced in all shapes and sizes.

The Little Mermaid was released in 1989 and quickly gained approval from viewers of all ages. It starts as an aquatic adventure and then turns into the pursuit of love and “happily ever after” on land. Together with Ariel, the feisty mermaid, we have a human prince, a villain octopus, the unmissable sidekick pets and many more colorful characters.

[…] Just look at the world around you

Right here on the ocean floor

Such wonderful things surround you

What more is you lookin’ for? […]– “Under the Sea”, The Little Mermaid, 1989, Walt Disney Pictures.

If there is someone out there who doesn’t know what the little mermaid Ariel is looking for, I will rectify that immediately: legs. She wants legs. As she is the younger princess out of seven sisters and kind of daddy Triton’s favorite, she doesn’t have much left to wish for. Except for legs. She desires to be human so much that, while she compulsively collects man-made artifacts falling on the ocean’s bed from shipwrecks, she makes a reckless deal with a super-evil sea witch. After the deal is done, she sets off frolicking under the sun, finally part of our world.

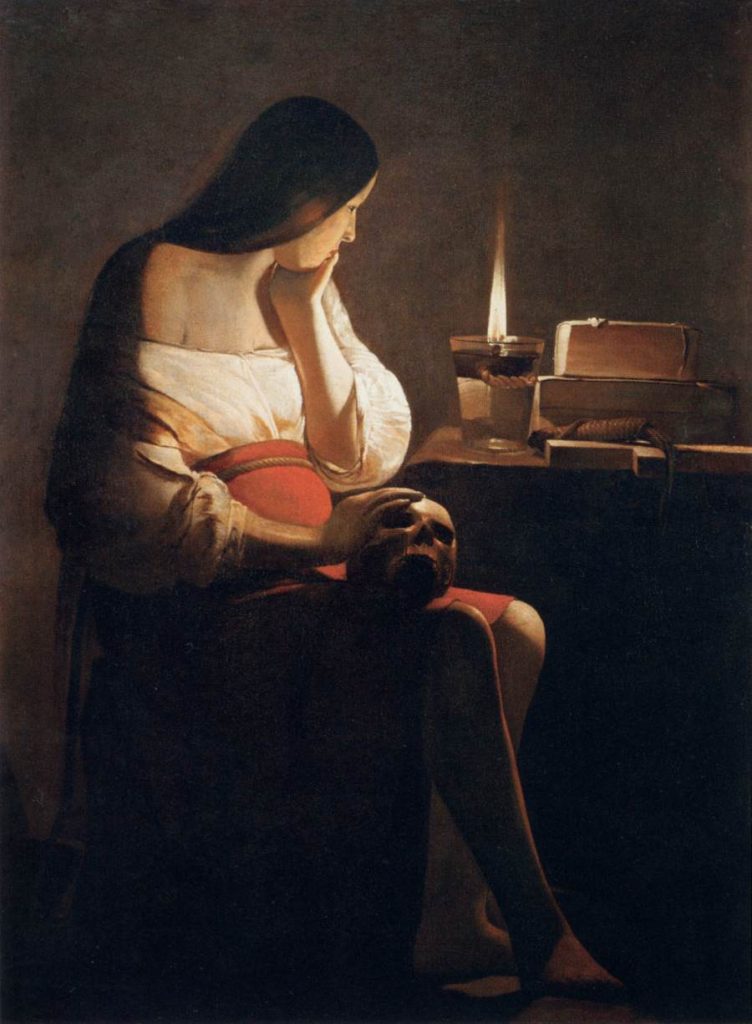

We will not follow her there, though. As it happens, hidden inside Ariel’s oceanic secret vault-cave, magically not melting away, we find our second art reference inspired by real art: Magdalene With the Smoking Flame, a celebrated painting by Georges de la Tour.

Disney’s artists seized the opportunity to embed in the movie such a splendid piece. The Little Mermaid’s fascination for human relics was the perfect pretext to fit in an actual painting. As an art and Disney lover, I find the thought very satisfying. And what a great copy of Georges de la Tour’s work it is!

Mary Magdalene has been a shining, iconic star throughout art history. During medieval times not so “shiny”, perhaps. (Read more about her in the article Why Is She So Hairy? Iconography of Mary Magdalene.) Never mind the Middle Ages, as George de la Tour was born and bred in the Baroque period. Characters showing deep feelings, and dramatic movements framed in dramatic scenarios were on every Baroque artist’s agenda. We don’t have a lot of movement here. None, in fact. Yet, there is as much drama as one could master, conveyed beautifully by De la Tour’s use of chiaroscuro.

This Magdalene is showing so much skin! It looks as if her flesh absorbed the candle’s light to then radiate it back at us, creating a powerful contrast with the darkness of the room. The nudity and sensuality belong to the renewed iconography of this biblical character, promoted by the Catholic Church during the Counter-Reformation.

With her right hand, she holds a skull, a typical memento mori, which literally translates as “remember that you will die”. Both the skull and the candle suggest that our time is finite. No wonder she looks so pensive. Once a sinner, Mary Magdalene repents. This transpires from her pose and the few symbolic objects in the painting: the cross, the books, and most obvious of all, the whip made of rope.

It isn’t surprising that they omitted the flagellating detail in The Little Mermaid movie frame. It is conveniently hidden by the princess’ hand. Perhaps it isn’t there at all. However, even if “Disneyfied” is just a touch, the truthfulness of the reproduction is laudable. Moreover, it is easy to understand why Ariel would keep this oil on canvas. I mean, look at Mary’s lower bits! Those are legs one could kill for.

Moving on to our third real art reference – the Disney movie binomial, let me tell you about Beauty and the Beast. It came out in 1991, I was six years old and I LOVED IT! Cynics will tell you that this story isn’t at all educational, as it shows that no matter how hairy a guy is if he is loaded he’ll get the girl in the end. Nonsense! Well, maybe. Besides, all fairy tales and fables have multiple possible interpretations.

In this story, the usual buddy/pet is amiss (if one doesn’t consider the Beast as one). Instead, we can count on a multitude of animated objects, once human domestics. They were cursed and turned into furnishings. Hence they frantically try to get Belle to fall in love with their prince, the Beast, who was cursed as well. Love would break the spell, obviously. Belle, however, is held hostage there. The same cynics would talk of Stockholm Syndrome…

Anyway, while the talking furnishings plot in the high ceiling hallway, once again our dear Disney animators took the chance to display their knowledge of real art. This time one must really be looking for it. Let’s see if you can spot this art reference: it is the copy of an acclaimed tronie made by a Dutch painter, people wrote books and made movies about it, at the center of it there is a singularly big earring… Have you guessed?

If you haven’t, fret not, I am here for you! Like Ariel’s cave, a long, tall corridor gave Disney’s animators the perfect opportunity to squeeze into the movie frame a glimpse of true artistic mastery, dated 1665. Right in between the unimpressed clock and the nosy chandelier, hung on the wall underneath a big landscape, all wrapped in yellow and blue fabric, there is The Girl With the Pearl Earring by Golden Age painter Johannes Vermeer! Although out of focus and only in the distance, there is no doubt it is indeed that splendid, super notorious painting.

This beautiful, fair girl could be anyone. It is part of her charm and constitutes fertile ground for all sorts of speculations. That is indeed one of the reasons why this piece, relatively small in size, gathered so much attention. This observation, however, takes nothing away from the exquisite technique and the superfine rendering of the materials.

If I get started on praising her features (like the complexion of her skin, the softness of her partly open mouth, its moisture, the intensity of her gaze, the depth of her eyes) we would be here all day. One thing that is amiss is her eyebrows. Believe it or not, that has been the cause of a lot of academic research!

Recent studies revealed the presence of fair eyelashes, a curtain in the background (behind the girl’s head) and several pentimenti – when an artist amends the composition in due course, covering up discarded elements with a hand of paint. The big jewel is under scrutiny as well, as art historians speculate it might not be a pearl at all! By the way, it reflects the light and what looks like the white of the collar’s fabric underneath it, it is possible that the earring was made of silver, or even polished tin.

From a French to a Norwegian castle, we find ourselves in one of the latest and most cheered successes signed by Disney: Frozen. Children and adults around the world are mad about it! Well, my daughter and I are. It’s a total hit: two sisters, an icy curse, an icy mascot, trolls, fjords, and a bunch of very catchy songs. The Elder sister (Elsa) is cursed, so she is kept away from the younger one (Anna). They grow up in the same castle, in the kingdom of Arendelle, but never get to see each other.

As time passes and the movie takes us through several years in a few minutes (accompanied by one of the songs, of course), Elsa is locked in her room most of the time. Anna gets bored but is free to roam around as she pleases. Having this whole brand new castle to furbish, once again Disney’s visual artists gifted us with an exciting sequence: Anna, singing and skipping around the palace, shows us many paintings hanging on the walls. There are several reproductions of real art, some more faithful than others. Among the many, I would like to talk to you about The Swing.

In reality, the frivolous scene in the movie frames above alludes to a love triangle. I will show you the original in a moment. As it happened with the Magdalene with the Smoking Flame, this artwork was “Disneyfied” and there is nothing in it there that would require parental guidance.

Let it go! Let it go!

Can’t hold it back anymore!“Let it Go”, Frozen, 2013, Walt Disney Pictures.

Elsa, undoubtedly secondary to Anna in the context of this article, sings her heart out on the top of a snowy mountain. In the song Let It Go she talks about an existential change and release from fear. However, as I look at our fourth art reference, imagining the frill-covered lady singing the same words about her flying pink clog is rather amusing.

Here above you can find the original painting The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. It is a triumph of Rococo aesthetics. There is richness of movement, embellishments and refinement anywhere the eye can see. The French title, Les Hasards Heureux de l’Escarpolette is a convoluted statement in itself. It translates into “The Happy Coincidence of the Swing”. No wonder the English speakers looked at it and went: “Let’s call it The Swing”.

The lady in the painting is suspended mid-air in a very graceful pose. The swing’s motion causes the already mentioned pink clog to fly away. In the bottom left corner, hiding in a rosebush, we can spot a young man, enjoying the view of the lady’s petticoats. He is struck by delight and surprise, as his cheeks turn red. On the right sits the third figure in the painting, an elder man who pulls some ropes to make the swing go, with a serene smile on his face. All around them the vegetation is at a max level of lush and winged statues observe the indecency in stony silence.

The subject of this piece was so singular that the artist who was asked first to paint it rejected the commission. A further singularity was that the commissioner (a gentleman living at court) decided to remain anonymous. Monsieur Fragonard, however, had a stronger gut and perhaps the fervid imagination required to do the job. He accepted, creating this rather libertine scenario. The young lover represented the commissioner, the swinging lady his favorite amorous partner, and the smiley, unaware old husband a well-known bishop of the time. Scandalous! Yet, a perfect match for the juiciness of the Rococo artistic registers.

This art reference hunt took us to many places, overland and under the sea, through different centuries. It hasn’t followed the Disney movies’ chronological timeline, but rather that of the art pieces. We are past the Rococo French period, falling into the marvels of the 1800s and its avant-gardes. Before showing you the excellence of this art reference, let me tell you about the movie we can spot it in: Brother Bear.

It was released in 2003 and, despite the tepid reviews it received, it was an instant success at the box office. It is set in a post-ice age Alaska, where nature and men coexist in a world ruled by spirits. The plot is dramatic and soulful, a long physical journey across the country and a mental one, towards understanding others and consciousness of oneself.

This art reference does not appear immediately, as it is nestled and well hidden within the end credits. Do you know the saying ‘good things come to those who wait’? Well, for the art and Disney lover, it couldn’t apply more than in this case!

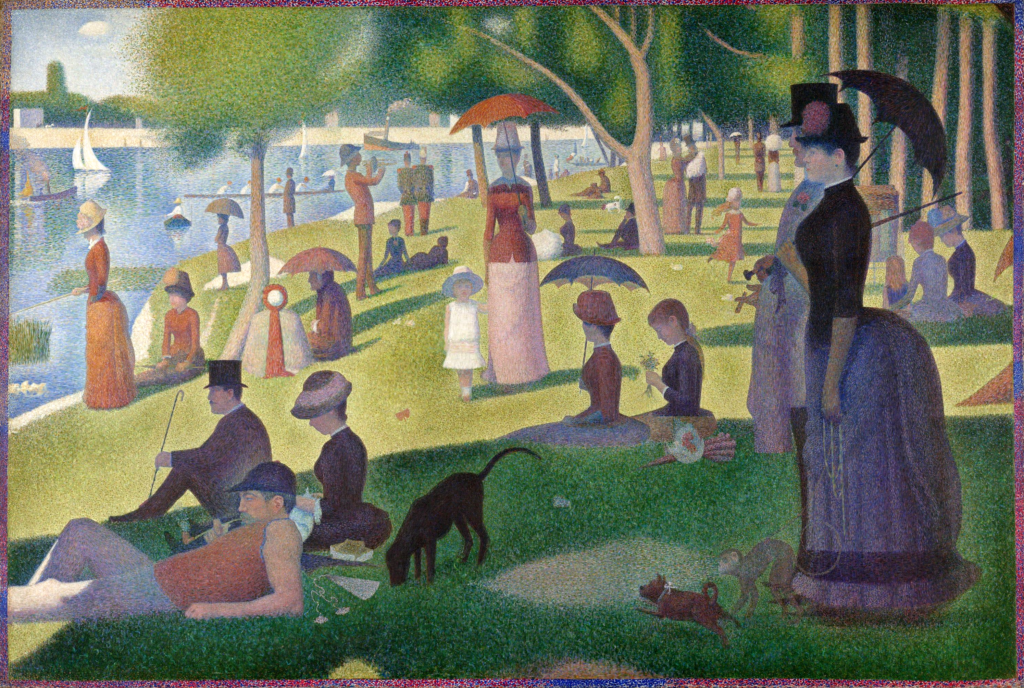

Below you can see the movie frame we are interested in. Koda the bear cub, while he tries his paw at prehistoric rock painting, has reproduced the core of the worldwide acclaimed masterpiece A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, created in 1884 by French avant-garde artist George Seurat. We can spot in the bear cub’s copy many of the characters depicted by Seurat. The little bear is adding the finishing touches to the black dog’s tail. All standing and sitting figures are exactly where they are supposed to be, holding their shades, canes, flower bunches and exotic pets (a monkey on a leash). This is a very accurate reproduction!

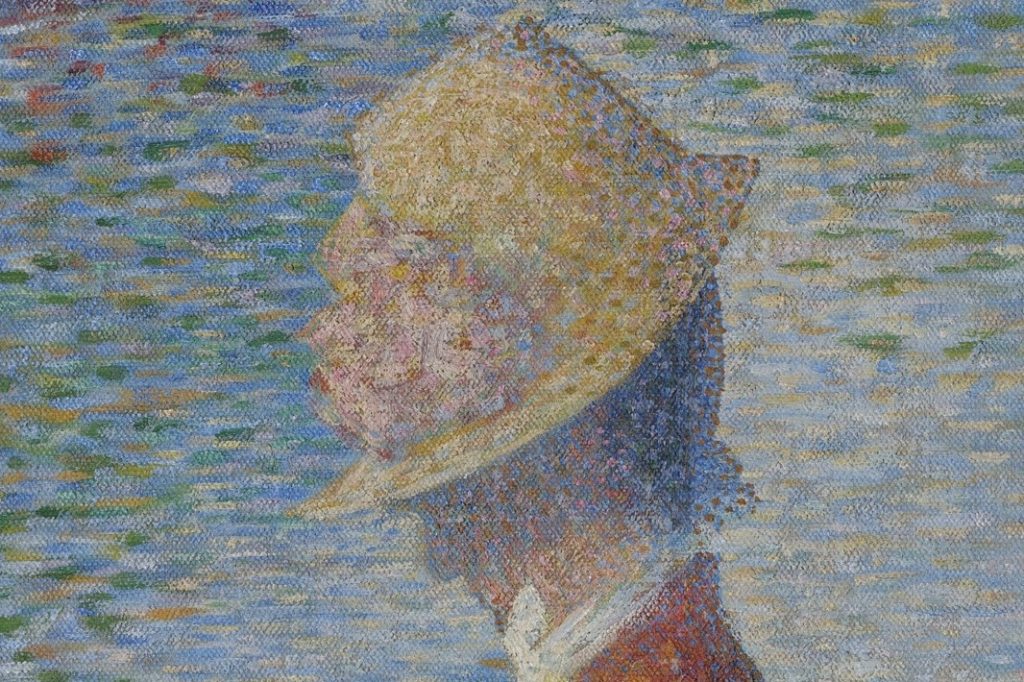

Together with being a rather large painting (207.6 x 308 cm), what surprises and makes it captivating is the knowledge that each element that our eye can appreciate on the canvas is composed of thousands of dots.

See, this piece was like a very technical and successful scientific experiment. Pointillism relies on our brain to do a lot of unconscious work by looking at the wider picture and assembling instantly many spots of color into a detailed shape. The closer one looks, the more the forms vanish and all one can see is a multitude of individual specks of paint.

Seurat developed this new technique in partnership with Paul Signac, branching out from the Impressionist movement. They received unimpressed reviews from the critics of the time. In fact, the term “Pointillism” was coined to deride the artists (as much as Impressionism was)… Well, the joke is on them! The value of this Neo-Impressionistic trend, incorporating science and art in one creative effort, today is considered the core of further important artistic variations and techniques. The bear cub knew it.

Our wandering far and wide and back and forth in time, hunting for art references in Disney movies, gave me a big inspiration. All is well, as we have arrived at a rather special place.

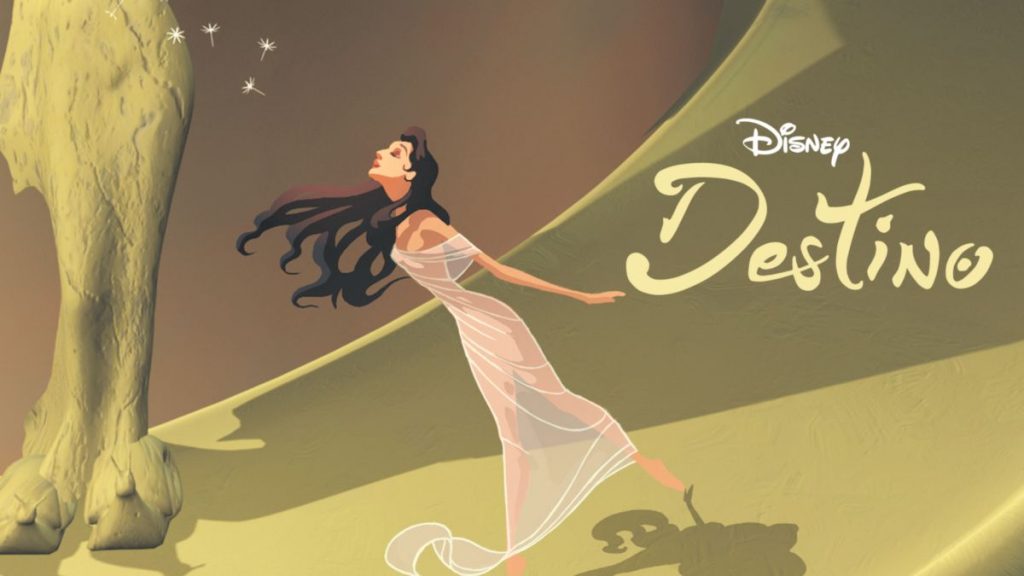

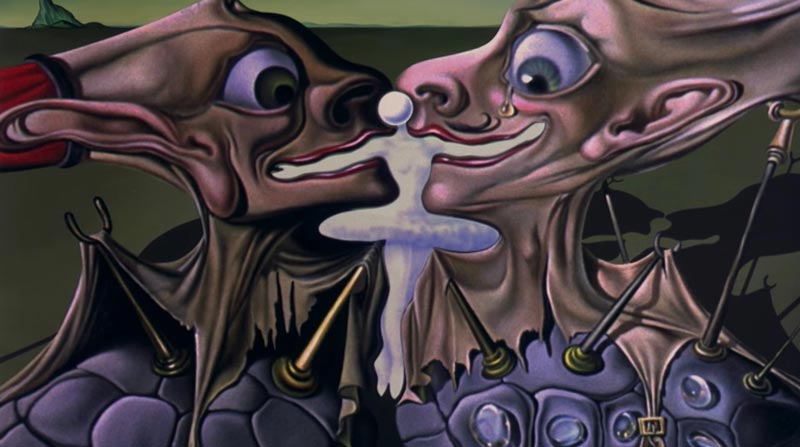

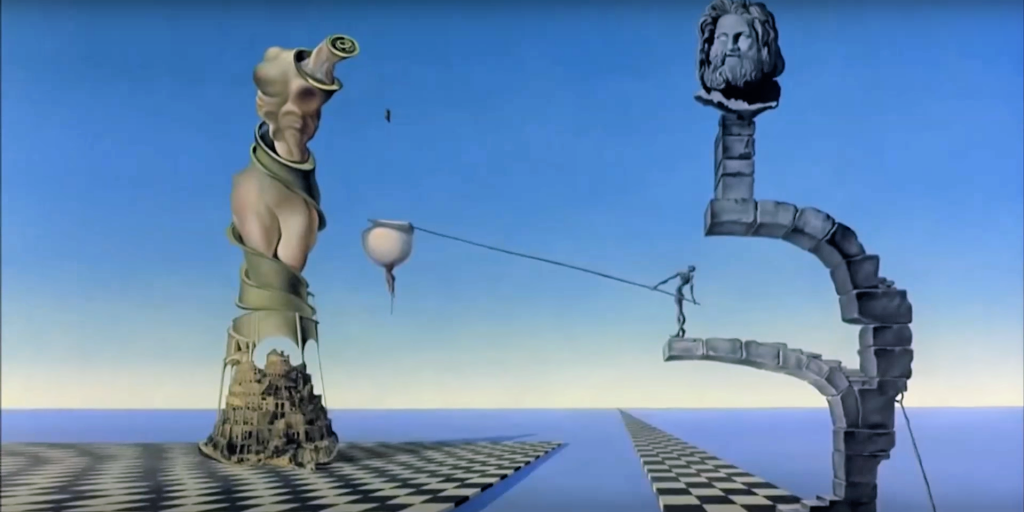

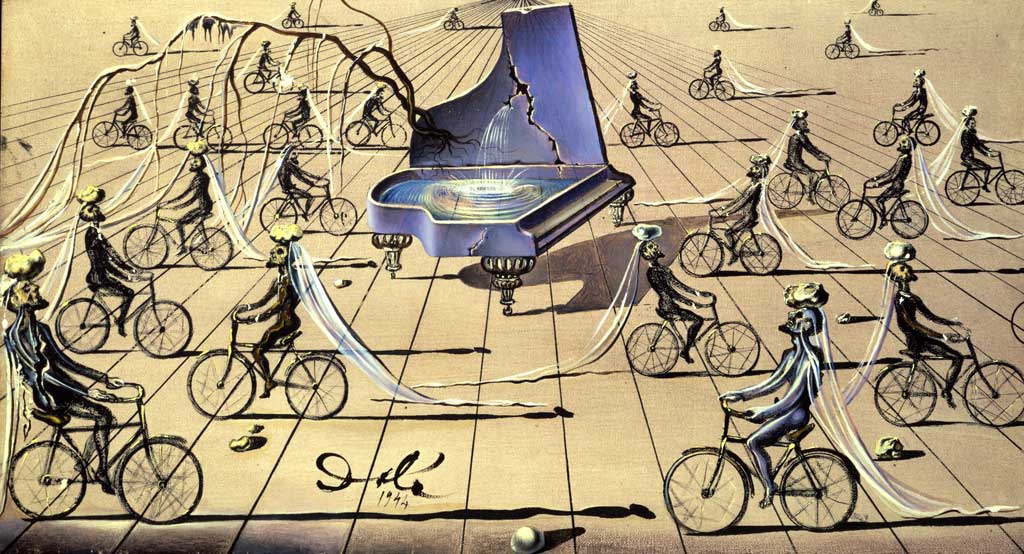

This Michelin starred fine dining restaurant would be called something like Chez Les Deux Ds (At the Two Ds). Destino (Destiny) was a project on which Walt Disney and Salvador Dalí started working back in 1945. As it was only released in 2003, it took 58 years for this short movie to come to life. However, it isn’t like they worked on it for that long. Due to financial struggles during WWII, Destino was placed on hold and then half a century passed.

Despite its delayed arrival, this short was worth the wait. The final product is mostly traditional animation and only includes a touch of computer-made elements. All we hear for seven minutes is the passionate and melancholic music composed and performed by Spanish artists. There is no dialogue, however, it is hardly amiss as the images speak volumes about the ill-fated love story between Chronos (here the personification of Time) and the human Dahlia.

It is a showcase of two men’s artistry, as they were ready to merge their ideas and create something new. In 1999 Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew decided to bring the project back to life (thank you, Mr. Nephew!). It took a team of 25 animators to decipher the old storyboards. We thank their determination too, as the result is exquisite!

The unlimited power and potential of dreaming is the engine at the center of the Surrealist movement and very organically the animators take us through continuous changes of implausible scenes. Sizes and shapes matter not, as the fluidity of this reverie brings on screen, one by one, every iconic Dalí painting. Melting clocks, crawling ants, enormous telephones, crowds of cyclists balancing stones on their heads, deconstructed architecture, and bodies (just to mention a few).

It is, in my opinion, a must see! You might find it rambling, hard to follow, if you will look for any logic in it. Whereas it is about the flowing of the unconscious mind (Salvador Dalí’s, specifically). This is why it was meant to be our grand finale. The whole short is the best art reference you’ll ever see! Why, it is a feast for the senses of the art and Disney movie lover, from the beginning to the very end!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!