Plunder and Survival: Suzanne Loebl’s Account of Nazi Art Looting

Written by Holocaust survivor Suzanne Loebl with Abigail Wilentz, Plunder and Survival (Bloomsbury, 2025) traces the Nazi looting of art across...

Javier Abel Miguel 16 February 2026

The National Gallery’s major fall exhibition showcases Neo-Impressionism from the Kröller-Müller Museum. There are lots of dots but are there other reasons to see the show? It is a narrow range of artists largely from a single collection, but the curators want to persuade you that these painters had radical ideas and a significant influence.

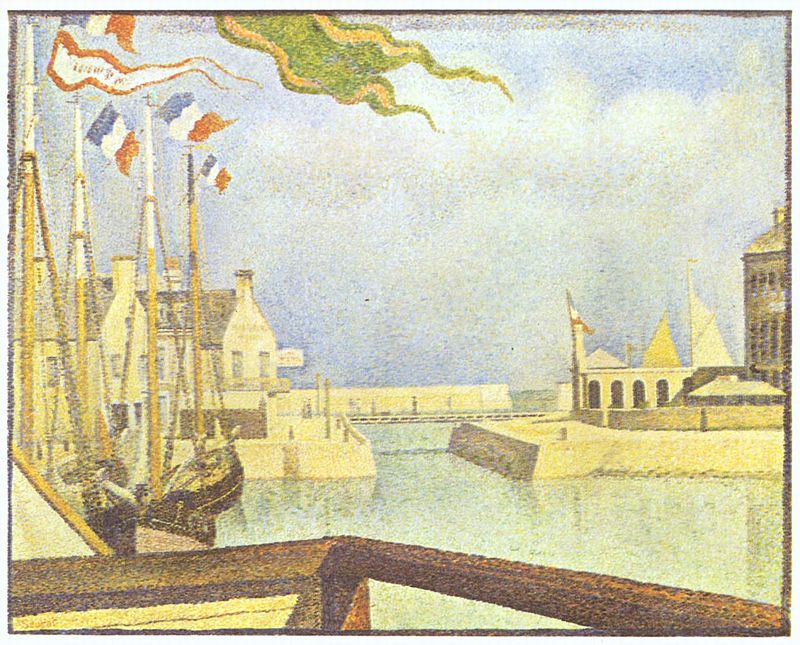

Georges Seurat, Sunday at Port-en-Bessin, 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The work of Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Paul Signac (1863–1935) is often labeled as Pointillism, a dismissive term coined by critics who thought they had reduced painting to a series of dots. The artists themselves preferred the term Divisionism or Neo-Impressionism to describe their new, more scientific approach to Impressionist subjects.

This centered on the color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, who argued that colors were intensified when juxtaposed with their complements, for instance, blue and orange, and the visual impact of colors depended on their context. The Impressionists had exploited Chevreul’s ideas, but the Neo-Impressionists wanted to do so more rigorously, using small, regular dots and making the viewer’s eye do the work of mixing and contrasting the pure colors.

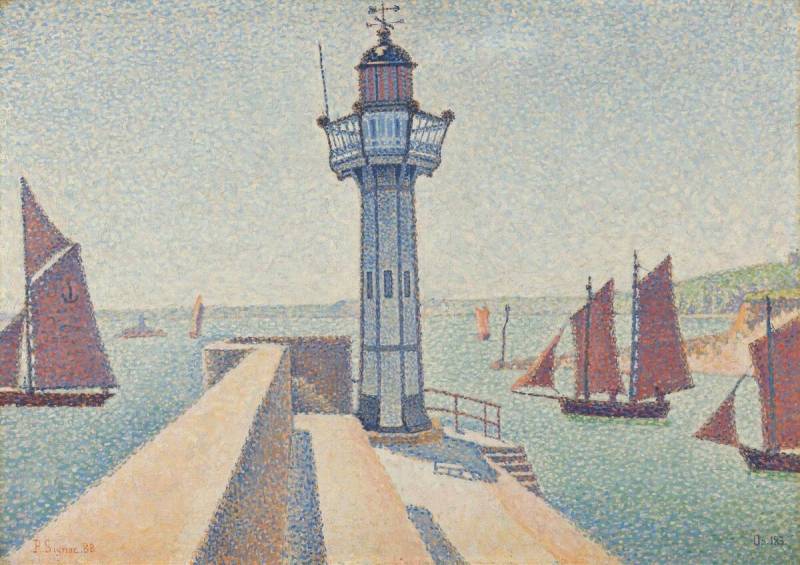

Paul Signac, Portrieux, the Lighthouse, Opus 183, 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The opening room of the Radical Harmony sets this context and gently acclimates visitors to Neo-Impressionism with a series of landscapes and seascapes. There are obvious links back to Impressionist subjects and locations but the paintings themselves deliberately avoid the immediacy and naturalism of the earlier works.

This is partly an inevitable result of the Pointillist technique which creates a structure and rigidity, and close-up gives an element of abstraction to the picture surface. Flags do not flutter in the breeze; waves seem frozen; time stands still. However, the artists also make compositional choices. Seurat deliberately emphasized that these are constructed images with his inclusion of painted borders. Signac numbered his works like musical compositions. Both focused on flattened geometry, strong lines, and angles which accentuate the two-dimensionality of the picture plane.

Vincent van Gogh, The Sower, 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

Radical Harmony establishes Neo-Impressionism as a movement with an opening text which includes Chevreul’s color wheel. Alongside, the exhibition introduces Helene Kröller-Müller, the German-born collector whose works form the basis of Radical Harmony. The Kröller-Müller collection, which is based in Otterlo, the Netherlands in a museum purpose-built by Henry van de Velde (1863–1957), has not only over 250 works by Vincent van Gogh, but arguably the world’s finest Neo-Impressionist collection.

Kröller-Müller, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist, who married a Dutch entrepreneur. They moved to Rotterdam in 1900, becoming one of the richest couples in the Netherlands. From 1907 Kröller-Müller used her huge spending power to become a pioneering female collector. She increasingly bought directly from the artists she admired, and eventually amassed over 12,000 items including furniture and ceramics, as well as paintings.

Jan Toorop, Morning (After the Strike), 1888–1890, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The curators’ central argument in the National Gallery’s exhibition reveals that these painters were political as well as artistic radicals. Using Camille Pissarro as a bridge between Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, and the anarchist politics which led him to represent idealized peasant communities, the show groups together a number of images of urbanization, industry, and workers.

Many of these are striking in themselves. Jan Toorop‘s (1858–1928) Morning (After the Strike) shows a desolate, chill dawn as a widow and child follow a striker’s corpse being carried away. Alongside Evening (Before the Strike) it forms a melodramatic contrast where the beauty of the colors seems strangely at odds with the subject matter. Toorop’s loose, large pointillist dots generate a smudgy atmosphere which suggests grime and weariness.

Georges Lemmen, Factories on the Thames, 1892, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

These so-called radicals were, however, often surprisingly reluctant to actually show workers. Their cityscapes and port scenes are often almost devoid of figures, and those in the scenes are incidental. Georges Lemmen‘s (1865–1916) Factories on the Thames represents industry as silent and empty, monolithic geometry lit by an elegiac sunset. Toorop’s sun-bleached Bridge in London has none of the sense of hustle and movement found in Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge series.

In fact, many of these artists seem to retreat to the countryside. The sole example of Van Gogh’s work in the exhibition, The Sower, is a timeless, almost Biblical subject with a deeply symbolic sun radiating across the sky. Anna Boch‘s (1848–1936) During the Elevation is a conservative religious scene of an overflowing church and traditionally dressed congregation. You end up wondering just how committed to radical politics these artists really were, despite what the curators are trying to argue.

Anna Boch, During the Elevation, 1892, Stadsmuseum Oostende, Ostend, Belgium.

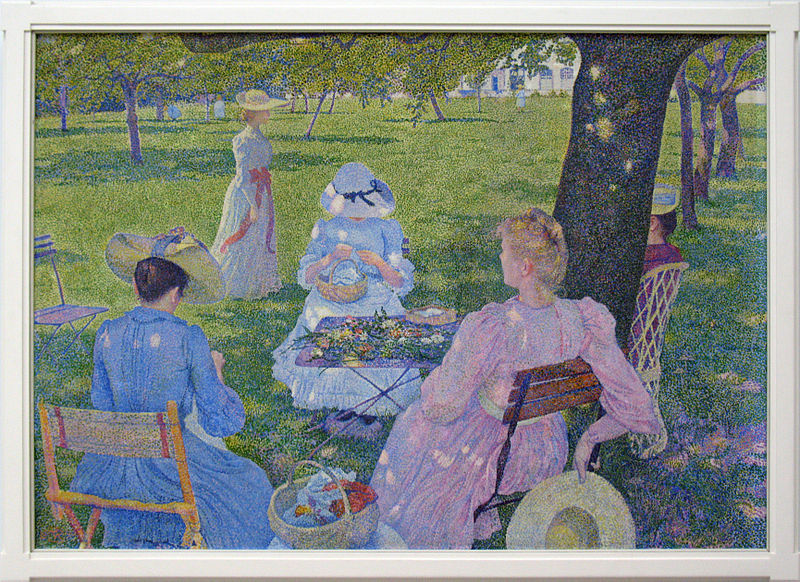

The next sections of the exhibition reinforce this with a series of very middle-class portraits and scenes of domesticity: well-dressed figures in well-furnished rooms. Théo van Rysselberghe‘s (1862–1926) In July, Before Noon is Impressionism in all but name, with its snapshot-like composition of leisured ladies, sunlight dappled like powder puffs on their dresses. In contrast, Signac creates an almost sinister claustrophobia in his Dining Room, Opus 152, with rigid profiles and a muted palette.

Toorop’s Portrait of Marie Jeannette de Lange combines a delicate naturalism in his representation of the sitter with a background so packed with objects and pattern that it becomes a Symbolist representation of her character. His use of a restricted tonal range and heavily impastoed dots creates an almost sequin-like effect as the paint catches the light.

Théo van Rysselberghe, In July, Before Noon, 1890, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The star of the show, not seen in the UK since the 1950s, is Seurat’s monumental depiction of can-can dancers (La Chahut is the name of the dance), high-kicking with fixed smiles and watched by leering figures, as the orchestra plays. The painting takes center stage against a dramatic, deep purple wall, although it hardly needs such theatrics.

The composition is influenced by Edgar Degas’ concert and ballet pictures, as we are positioned in the audience looking through the musicians. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was also producing images of can-can dancers and performers. However, Seurat does not want to put us in the midst of the mayhem. Rather, he presents the scene and the figures within it, as alienated and detached, frozen in an unreality of sleazy sepia. Life is a cabaret, but it doesn’t look much fun.

Georges Seurat, Le Chahut, 1889–1890, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

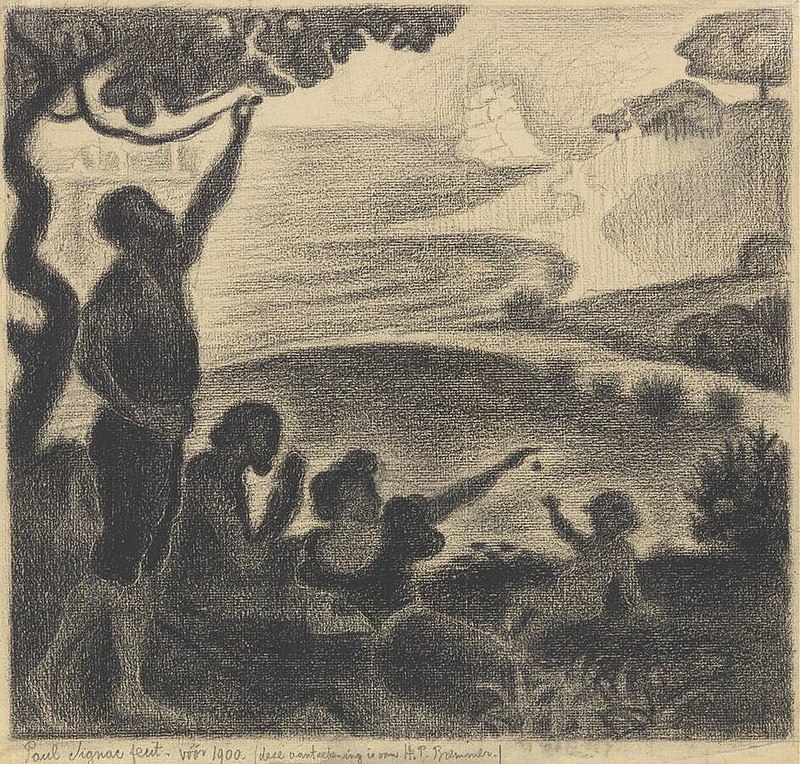

Although Neo-Impressionism was rooted in color theory, some of the most striking works are monochrome drawings. Seurat developed a technique of using coarsely woven paper and soft crayon to create a dot-like stipple effect. Signac’s smudgy outlines in study for In the Time of Harmony have a similar visual impact. In contrast, Georges Lemmen’s detailed portrait of Jan Toorop is constructed entirely of visible dots.

Increasingly complementary color contrasts are rejected in favor of tonal uniformity. Rysselberghe’s Coastal Scene is a study in blue, and van de Velde’s Twilight is dominated by violet hues. The curators choose to end the exhibition with a series of landscapes which emphasize this sense of peaceful harmony, although works like Johan Thorn Prikker’s (1886–1932) Basse Hermalle, Sun at Noon hint at the possibility of something more radical. His sparse pastel dashes, which harken back to van Gogh’s brushwork, create a simplified, flattened abstraction in which the landscape seems almost incidental.

Paul Signac, Study for In the Time of Harmony, 1893–1895, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The National Gallery‘s Radical Harmony exhibition features many beautiful works of art. It introduces lesser-known artists and has at least one show-stopper in La Chahut. Equally, it attempts to prove that Neo-Impressionism, which is often seen as a nerdy backwater, is actually radical and compelling.

The problem here is that they do not join the dots and link these artists forward to Henri Matisse (who gets only a mention), Piet Mondrian or other groups like the Italian Futurists who used pointillism. Granted, the curators are restrained by what is in the Kröller-Müller collection, but they borrowed from elsewhere to include works by Anna Boch.

Ultimately, then, it is less “radical” and more “harmony,” but that is no bad thing. It is a Zen-like exhibition which encourages you to take your time, breathe deeply, and appreciate the deceptive complexity of the works.

Radical Harmony. Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists is on view at the National Gallery in London until February 8, 2026.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!