Form Follows Vision: 10 Iconic Designs from the Bauhaus Movement

As modern life demanded new ways of living at the beginning of the 20th century, the Bauhaus responded with radical designs. We explore 10 iconic...

Lisa Scalone 20 June 2025

27 January 2025 min Read

Until 1972, the Museen zu Berlin exhibited, among other things, a teapot and its accompanying set. From above, the teapot is around 22 centimetres long, 13,5 centimetres wide, and 13 centimetres tall. Its chrome finish gives an oil-surface ripple to the reflections of objects around it, as it shifts from dark to light to dark in its metallic gradient. This isn’t the kind of teapot we’ve seen on our elderly relatives’ coffee tables, with elephant trunk spouts and floral finishes. No, the chrome surface and stunted, resentment of the spout of this teapot places it firmly in the sphere of Modernism.

Aesthetically, it is indistinct from any other piece of kitchenware from the early modernist period: mass-produced, purposefully unremarkable, and entirely functional. The Bauhaus produced many similar pieces. Except, this teapot isn’t from the Bauhaus. It predates the Bauhaus and the advent of Modernism by over a decade; it predates the Werkbund too. This piece, from 1904, is the work of one man, not the result of a movement: Henry van de Velde.

The clue to the artist’s identity lies in the teapot’s handle. Whereas the later, more anonymous work of the Bauhaus had functional and non-descript handles in keeping with its reductionism, this handle is ornate and a work of art in itself. Rather than the bare straight lines and semi-circles of the Bauhaus, this handle, carved from ivory, tapers to a point in the beautiful shape of a leaf – offsetting the chrome scarcity of the rest of the piece.

It is at once a piece that looks forward to the incoming wave of Modernism and back to the artistic nuances of Art Nouveau. The handle is not just a handle, rather it’s an identifier of the artist for whom the stark realities of Modernism were a warning; a warning of the loss of autonomy and identity. It is a symbol of the fear felt by early 20th-century artists towards the disintegrated and chaotic urbanity of industrialisation. And yet, what is also apparent in the handle is van de Velde’s acceptance of the industrial as a tool for synthesis, in which beauty and artistic individuality need not be sacrificed to the machine nor the machine sacrificed for artistic integrity. In one small, ostensibly inconsequential, piece we can see at once the inexorable development of the modernist aesthetic and the resistance and final gasping breaths of artistic autonomy before it surrendered to industrial simplicity and reduction.

It is no coincidence that Henry van de Velde’s work of the early-1900s bears a striking resemblance to work produced two decades later at the Bauhaus. Van de Velde is intrinsically linked to the development of Modernism and originated the aesthetic the Bauhaus would adopt soon after its founding. In an artistic landscape still at the mercy of the ideals of Morris and Ruskin, van de Velde realised that eschewing the machine was a mistake. It limited art both aesthetically and economically. In mass production, van de Velde saw not an obstacle but a way in which to make art and beauty accessible to all, rich or poor.

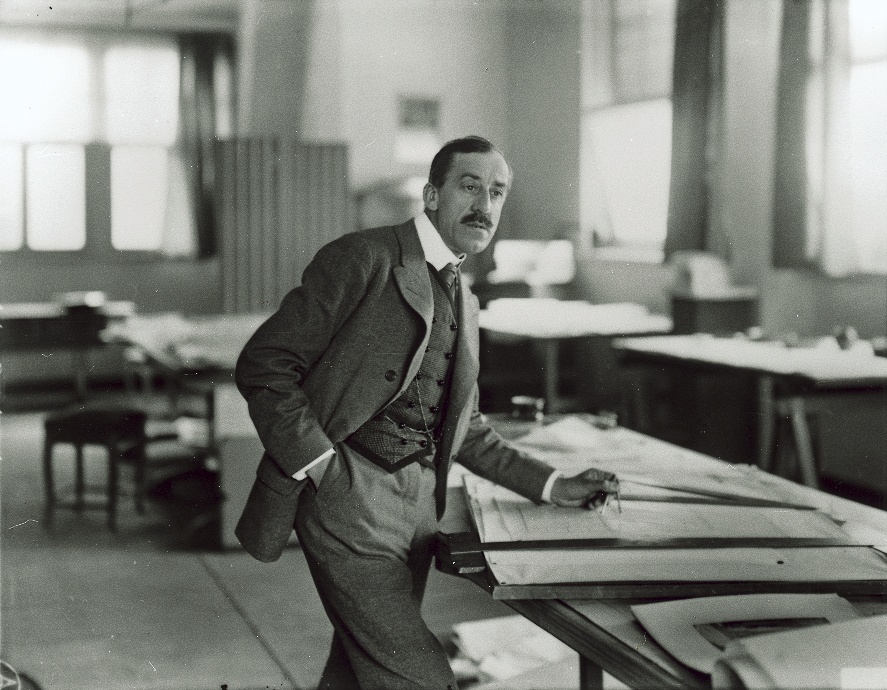

It was a romantic notion and in an era in which many of the old ways were falling out of favour, especially in Germany, there was little room for romance. Now, when we speak of the beginnings of Modernism, Henry van de Velde is rarely a name that appears in anything but the periphery, despite being a founder of Art Nouveau, a founding member of the Deutscher Werkbund, director of the Grand Ducal School of Arts & Crafts in Weimar, and an eminent architect in Europe through much of the first half of the twentieth century. Here is the progenitor of the modernist style, yet we do not remember his name or afford him any of the credit we give the canonical fathers of Modernism: Gropius, Le Corbusier, van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Inspired by natural forms and structures, particularly the curved lives of plants and flowers, and a reaction to academic art of the 19th century, Art Nouveau has its roots in the Arts & Crafts movement of William Morris and John Ruskin. Henry van de Velde found some refuge for his ideals in Arts & Crafts, but in accepting the value of mass production he was at odds with the fundamental beliefs of its founder.

In many ways, Art Nouveau was an ineffectual movement; neither capable of making great changes in the artistic landscape nor capable of moving those that appreciated it. As Theodor Adorno points out in Aesthetic Theory: “Its lie was the beautification of life without its transformation; beauty itself thereby became vacuous and, like all abstract negation, allowed itself to be integrated into what it negated.”1 Beauty for beauty’s sake could not move van de Velde for long, and this informed his decision to pursue the applied arts; motivated by the aspiration to apply art to life – both socially and moralistically.

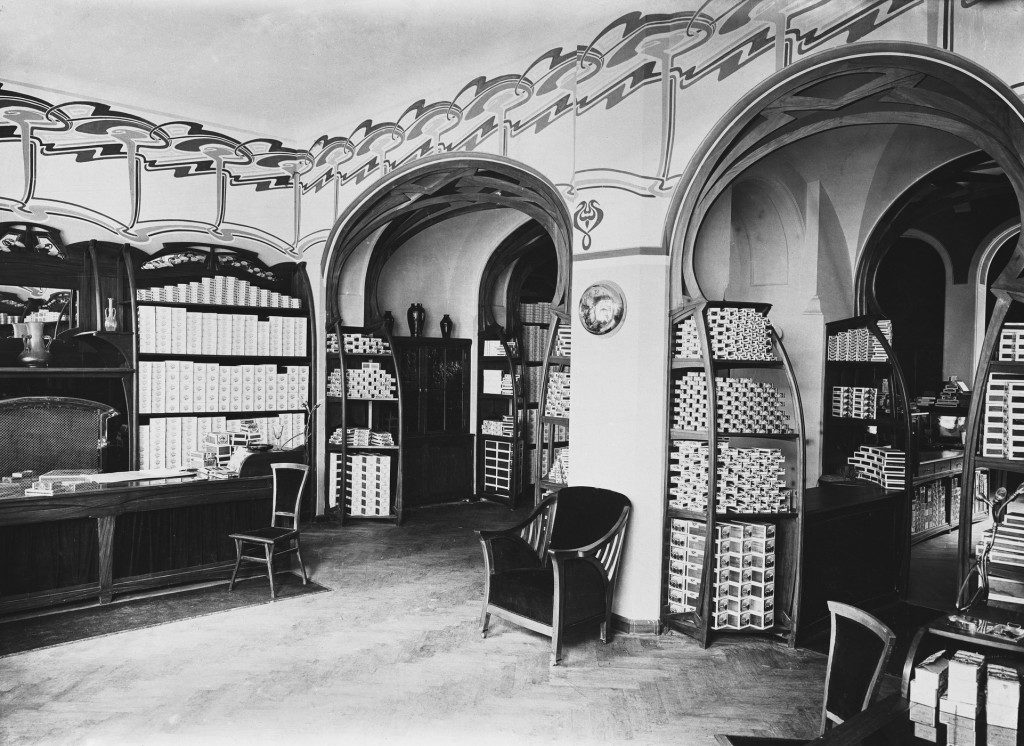

In 1907, the Deutscher Werkbund was founded by a group of artists including Adolf Loos, Hermann Muthesius, and Peter Behrens. Its aim was to bring art and industry together and, in doing so, move Germany forward and away from the traditional trappings that many felt were holding it back. While all members of the Werkbund accepted industry, for some time they were uncertain how exactly to utilise it in the synthesis of art and the machine. But as time went on, support grew for the concept of setting an artistic standard.

In the Werkbund van de Velde found both allies and adversaries to his ideals. In the power of mass production, van de Velde saw a potential to uphold the virtues of Arts & Crafts – namely that of artistic quality – while rejecting the exclusivity of the movement itself and providing an affordable, and repeatable, product to the masses. His objections to the proposed standardisation were artistic, not fundamental. A reiterating model was not the problem, it was that the model would have no soul; that one set of defined rules would render the individuality of the artist obsolete.

Wagner proposed a unification of art in 1849 in Das Kuntswerk der Zukunft (The Artwork of the Future) as a revolutionary opposition to the capitalist division of labour. Van de Velde, however, proposed his Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) almost as a compromise to the hard lines of standardised Modernism. It was a resistance, of sorts, but also seen as an opportunity to provide therapy to anxiety-driven consumerism of industrialisation with the redemptive powers of art and beauty.

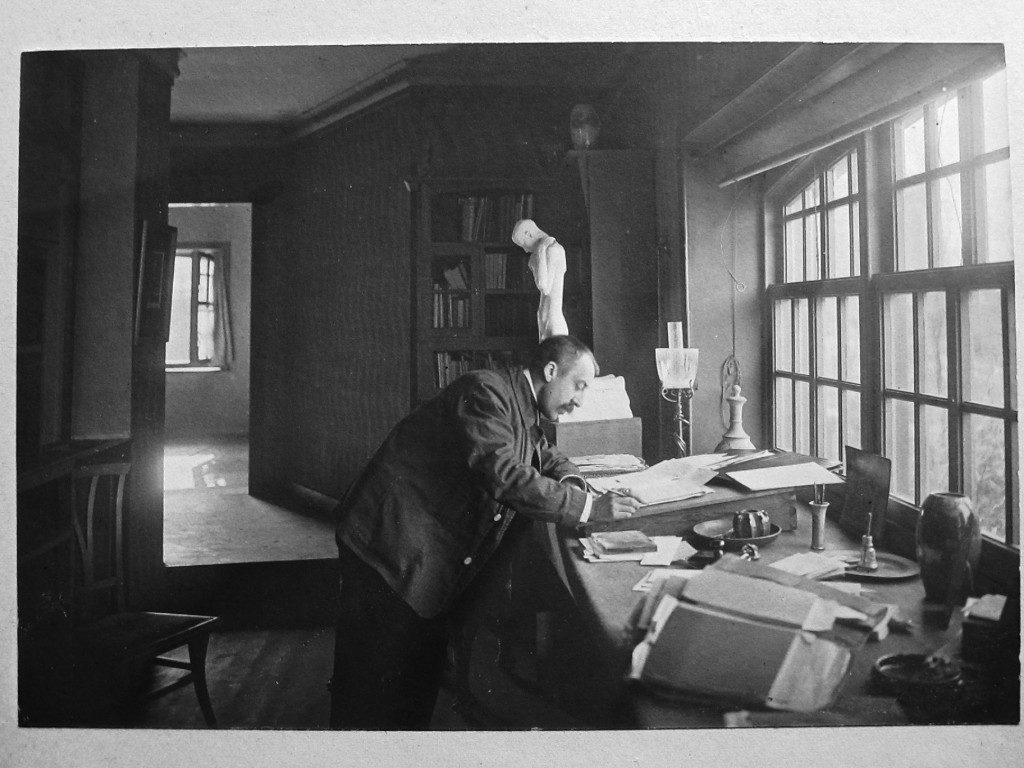

For the growing voice of standardisation, nothing less than a complete rejection of the Arts & Crafts and adoption of a set paradigm would do. Henry van de Velde’s individualism had him at odds with this establishment and led to one of his – and the Werkbund’s – greatest conflicts. It was at the 1914 meeting of the Werkbund that the debates and contradictions that plagued its early days came to a head. On one side were Henry van de Velde and the supporters of artistic autonomy, on the other Herman Muthesius and those who felt that, in order to satisfy the Werkbund’s founding ethos of artistic and industrial synthesis, standardisation was the only answer.

This debate was a turning point for the progress of Modernism, in that it paved the way for ground rules to be established that would govern Modernism for decades to come. To hear van de Velde tell it, it was a monumental struggle that saw “thunder and lightning sounding outside” as he “demanded the rights to free, independent, creative work…”2 Whether van de Velde’s rather dramatic account, written in his nineties, can be relied upon is uncertain. However, there is no doubt that the debate and its results sent shockwaves through the burgeoning modernist movement. With standardisation’s victory, Modernism shifted from a confused and developing ideal to the more familiar reductionist movement we know today.

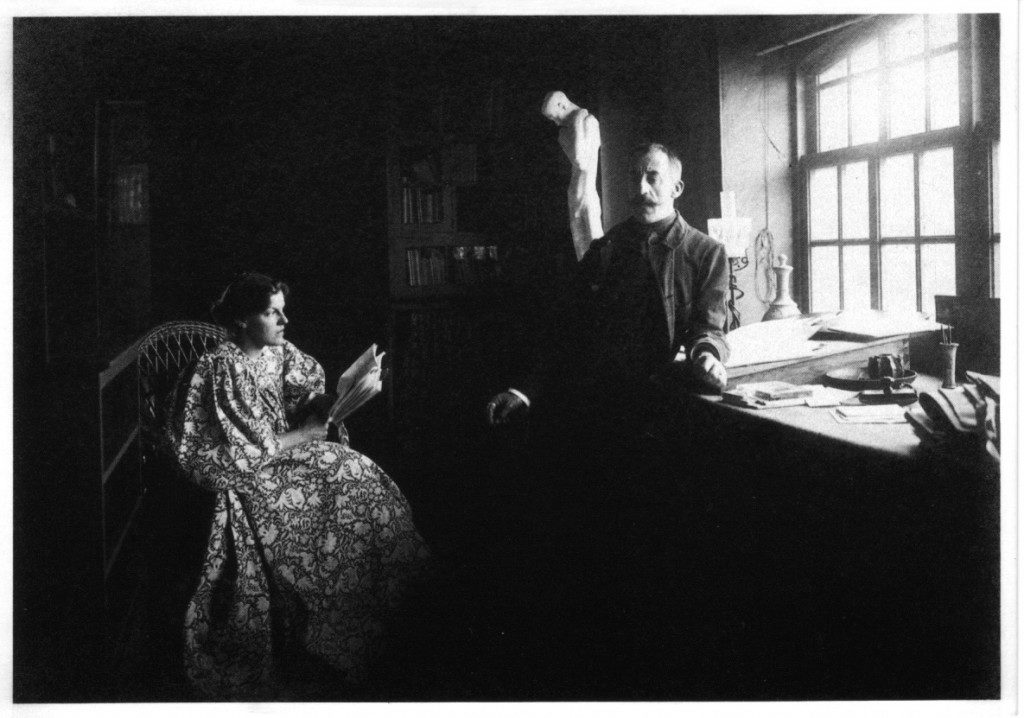

For van de Velde in particular the loss of autonomy was a cruel blow, offensive even. The idea of soulless art hurt him. As far as he was concerned, art, whatever form it took, was to be a living breathing thing, not a dead space. In writing about van de Velde’s contemporary, Adolf Loos, Aldo Rossi said, “It does not make much sense to talk about the interior and exterior of a building, because the entire construction is determined by a single, synthetic conception, through floors and spaces … the conception of the house becomes a concept of life.”3 For van de Velde, this was what synthesis meant, not the “machine for living in”4 ethos that emerged from the Bauhaus.

The defeat in 1914 was one that he never recovered from. After leaving Germany in 1917, he moved to Switzerland and then back to his native Belgium to teach at Ghent University.

Despite the effect of his loss, Henry van de Velde resurfaced in the thirties as Belgium’s eminent architect and designer. While his work internationally spoke of a movement to come – the Werkbund theatre, tragically closed at the outbreak of the war and did not reopen, and in particular the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands – it is with the Boekentoren in Ghent and the Charlemagne Building in Brussels that Henry van de Velde demonstrated his true prowess. Rather than grey modernist tombstones, here van de Velde created buildings as at home on a skyline dotted with church steeples as they are beside even the most modern skyscraper.

How then can a man whose work pre-empted the aesthetic of Modernism and who played a part in laying the foundations for its emergence, and who successfully brought together industry and artistic beauty while retaining his autonomy, be so nameless in the list of founders of Modernism?

As touched upon, Henry van de Velde found himself on the losing side. Progressive as he may have been for the arts, he was also keen to uphold many traditions that just didn’t fit in the artistic landscape of pre-war Germany. The impression this gave was of trying to preserve the ornamental and extraneous; seeking to retain those outdated tenets that many felt were holding Germany back. The old clichéd adage rings true: history is written by the victor. Muthesius’ standardisation won out and van de Velde’s unwillingness to drop the mantle of artistic individuality proved a major part of his undoing.

And yet, he also suffered for not being German in an increasingly nationalistic Germany. Throughout his career, he was referred to as “The Belgian van de Velde.”5 And, though he didn’t know it, the Grand Duke of Weimar, with whom he had founded the Grand Ducal School, as opposed to a non-German running his college. Even before the outbreak of the First World War, he was looking to replace van de Velde with a German. In the face of this growing sense of nationalism, the contributions of a Belgian were downplayed – not least by Walter Gropius, van de Velde’s replacement, and founder of the Bauhaus.

Gropius made a concerted effort to deemphasise Henry van de Velde’s contributions and assert his own position at the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923. But in speaking of the “total work of art” and “an orchestral unity” being “inherently related to architecture”6 he was, in fact, echoing van de Velde’s Gesamtkunstwerk and his own treatment of the modernist problem. Gropius’ tenure as head of the Bauhaus was not without contradiction, of which this was only the first – one needs only look at the attitude towards women in the Bauhaus to see that – and in many ways, Gropius, despite his attempts at autonomy from his predecessor, was more indebted to van de Velde than he liked to admit.

Then there was van de Velde’s record in the Second World War and the perception – spread by resentful colleagues – that when, like many of his compatriots, he was obliged to help the occupying Germans, he was, in fact, collaborating. Unfounded as it was, the allegation stayed with him until he retired to Switzerland after the war to write his memoirs. And it was in Switzerland – an expatriate yet again – that Henry van de Velde died in 1957.

Perhaps our purpose is not to exalt Henry van de Velde above any other as father or inventor. There are many contradictions in Henry van de Velde: the artist and industrialist and socialist, Arts & Crafts and the Werkbund, Nouveau and Modernism, the individualist and the mass-producer, the Belgian painter and the German architect. Ostensibly these appear as paradoxical, but this is a view afforded to us by hindsight. In looking at the contexts of all these things, we can see the intrinsic link between them: a progression from one to the other that van de Velde was a major part of.

More than that, in looking at the progression from traditionalism and the Arts & Crafts to Modernism, van de Velde’s name looms large, despite attempts to limit his involvement in retrospect. Rather, perhaps our purpose is to highlight those that was never sanctified by the International Style in the way Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright were. Henry van de Velde and, arguably, Adolf Loos and Peter Behrens with him, represent a vital portion of the timeline of Modernism. These names are not wholly lost to history but are rarely given their proper due. These are the masters of masters, whose tutelage and groundwork paved the way for the canonical four to gain their celebrity. Their work was no less revolutionary or innovative, but it came in a period of confusion; where the rules of the game had not yet been established.

The Bauhaus itself was built upon the foundations of van de Velde’s own design, both physically and idealistically. But there is an illegibility to Henry van de Velde’s credo that hindered him and much as he was never German, he was never entirely modernist either. Whether it be nationalism, his individualistic streak, or the perception that he collaborated with the occupying Germans, a great deal has worked to wipe van de Velde from the history of Modernism.

Even his own work conspired against him. Whereas other designers are remembered for their stylistic signatures, van de Velde’s aesthetic is so replicated, so influential, that he is now indistinguishable from the rest of the modern landscape. It is a testament to his lasting influence that his designs of the modernist period are so familiar today. However, though he has disappeared into the fabric of our daily lives, for those who know where to look there remain identifiers, among the anonymous sea that swallowed him, of van de Velde’s particular artistic voice: a handle, a leg, the curve of a gable – subtle shades of Art Nouveau that serve as clues to his great contribution, that have endured long after his name has been forgotten.

Theodor W. Adorno, (2013): Aesthetic Theory, translated and edited by Robert Hullot-Kentor, London: Bloomsbury.

Ernesto N. Rogers (1958): “Il mestiere dell’architetto” in Esperienza dell’architettura¸ second ed. 1966, now Milan: Skira 1997.

Henry van de Velde (1962): Geschichte meines Lebens, München: R. Piper & Co Verlag. Translations and editing by Geoffrey Bunting, 2017.

Le Corbusier, (1923): Vers une architecture, translated by John Goodman, Los Angeles: Getty.

Ibid, 3.

Gropius at the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923, cited from Matthew Wilson Smith (2007): The Total Work of Art: From Bayreuth to Cyberspace, New York.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!