Summary

- Bronzino’s early Pygmalion and Galatea, painted while apprenticed to Pontormo, depicts a statue coming to life and already reveals his distinctive Mannerist flair.

- Most of Bronzino’s career was devoted to painting the Medici family, and his portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armor captures both the Duke’s power and the artist’s signature mix of precise detail and cool detachment.

- In his chapel frescoes, especially The Crossing of the Red Sea, Bronzino turned biblical scenes into dazzling displays of movement and color.

- Saint John the Baptist blends religious symbolism with a sensual, almost secular depiction of the male nude.

- In Venus, Cupid, and Jealousy, Bronzino blends open eroticism with impossible, graceful poses, creating a puzzling Mannerist vision of love and envy.

- In his portrait of Laura Battiferri, the artist pairs Mannerist elegance with intellectual symbolism, portraying the sitter as a figure of intellect and grace.

- In the double-sided portrait of the Medici jester Nano Morgante, Bronzino uses a playful nude to parody classical ideals while demonstrating painting’s power to rival sculpture.

- Bronzino’s Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus turns the young duke into the mythic musician in a witty, ambiguous portrait of sensuality and power.

- His Portrait of a Young Man contrasts the sitter’s scholarly appearance with subtle homoerotic undertones, hinted at by the sensuous background figure of Bacchus.

- In his late masterpiece Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, Bronzino defied changing tastes with a dramatic, Michelangelo-inspired scene that embodies the fading brilliance of Mannerism.

1. Early Work—Pontormo’s Pupil

Christened Agnolo di Cosimo (1503–1572), Bronzino probably acquired his nickname because of his dark complexion or his hair color. He was a Florentine born and bred, apprenticed to Pontormo, another of the city’s great Mannerist artists. They worked closely together and many of Bronzino’s early works are difficult to distinguish from those of his master.

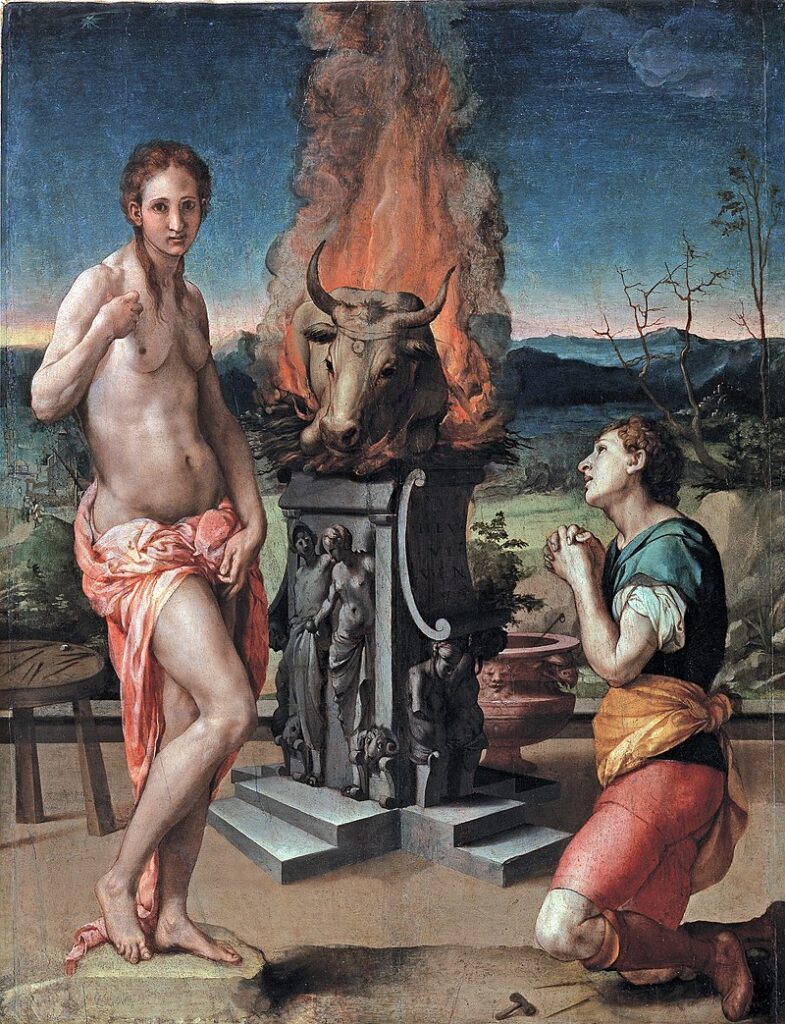

Agnolo Bronzino, Pygmalion and Galatea, 1529–1530, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

This early painting of Pygmalion and Galatea was, according to Vasari, painted as a cover for a portrait by Pontormo. It represents a classical narrative in which the sculptor, Pygmalion, asks the gods to bring his beautiful statue to life. Bronzino shows the moment Pygmalion’s prayer is answered: the stone transforming into flesh, the sculptor bowing in awe, and between them the bull which he has sacrificed to Aphrodite to get his desire.

In many ways, this is atypical of Bronzino’s work, and it has been suggested that the landscape was painted by someone else: Bronzino rarely bothers with detailed background later in his career. The composition is balanced between the three elements, but the dramatic flames and elongated figure of Galatea give the painting a Mannerist oddness. The story is supposed to be about love, beauty, and creation, but Bronzino centers it on a burning animal.

2. Medici Patrons

Most of Bronzino’s career was spent in the service of the rulers of Florence, the Medici family. Cosimo I de’ Medici became Duke of Florence when he was only 19 and commissioned Bronzino to paint many portraits of himself, his wife, Eleanor of Toledo, and their children.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici, 1543–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

This image of Cosimo in full armor was clearly very popular with the Duke: there are at least 25 slightly different versions painted by Bronzino and his workshop. Cosimo was at the height of his power here, and the portrait was likely commissioned as a celebration of his successful removal of Spanish troops from Florence. Ironically, although shown in armor, he achieved this by diplomacy and a financial settlement.

Cosimo is dressed as a soldier, but it is difficult to imagine him fighting. The highly decorative armor is more of a fashion statement. His long, delicate fingers are almost effeminate. He twists away from us, staring into the distance. The portrait exemplifies Bronzino’s style. Focusing on surface details like the engraving and the sheen on the metal, he brings his figures right up to the front of the picture space but at the same time gives them a distant aloofness.

3. Decorative Commissions

As well as portraits, Bronzino produced large-scale decorative work for his Medici patrons, most famously on frescos for Eleanor of Toledo’s private chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio. He covers every surface of what is a very small space with densely packed, writhing, and contorted figures. An illusionistic vault on the ceiling appears open to the sky, in which sit four saints; behind the altar is a Lamentation.

Agnolo Bronzino, The Crossing of the Red Sea, 1540–1545, Cappella di Eleonora, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy.

The Crossing of the Red Sea covers the wall on the right of the altar. The viewer is presented with a mass of partially clothed, anatomically exaggerated figures. Repeated reds and blues further confuse the composition. The main narrative is actually played out in the background, where the Egyptians are drowning and a blue-robed Moses stands with the Israelites on the right in the Promised Land. A second scene, front right, shows Moses, this time wearing red and distinguished with horn-like light-rays on his head, pointing to Joshua as his successor. None of this is very obvious, however: the figures that catch your eye are incidental to the story.

Like all his generation, Bronzino was heavily influenced by Michelangelo, particularly in his idealized, twisting figures. However, compared with the clear narratives of the Sistine Chapel, The Crossing of the Red Sea is confusing and disorienting. The religious message takes second place to Bronzino’s desire to wow us with spectacle and virtuosity.

4. Mannerist Religion

The cast of thousands extravaganza was one aspect of Bronzino’s religious art, but he also painted single-panel works: images of the Virgin and Child, and saints like this Saint John the Baptist. The figure is crammed into the frame in an oddly unnatural pose, which seems designed to show off the artist’s skill at foreshortening—especially the sole of the left foot – and the artificiality that this is a painting, not a window into reality.

Agnolo Bronzino, Saint John the Baptist, c. 1560, Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy.

Saint John is recognizable by the animal skin on his shoulder and in his right hand he holds a bowl of water ready for baptism. The background suggests wilderness, a cross made of reeds and a scroll reading “behold the lamb of God” are all traditional associations with the saint.

However, on another level, this is a very secular representation of a male nude: strong shadows emphasize the musculature of his shoulder, he has full lips and red cheeks. It has been suggested that it is, in fact, also a portrait of Giovanni de’ Medici, Cosimo’s son. That unsettling mix of the religious and the secular, artifice and realism makes this a Mannerist painting.

5. Mannerist Allegory

Arguably, Bronzino’s most famous and mysterious painting is An Allegory with Venus and Cupid in London’s National Gallery, but he repeated the theme with Venus, Cupid, and Jealousy. A frieze of intertwining foreground figures shows Venus and Cupid absorbed in each other’s gaze as they exchange arrows. The playful twins Eros and Anteros represent requited and unrequited love. Background space is almost non-existent, but fleeing in the shadows, Jealousy is just visible.

Agnolo Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, and Jealousy, c. 1550, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary.

The extreme eroticism of all the in-your-face nudity and the very 16th-century styling of Venus is counteracted by the lack of realism in the figures, whose flesh looks more like polished marble. The poses, especially Venus’s half-standing, half-reclining position seem almost impossible. The masks, lying on the ground, emphasize that nothing is straightforward and Bronzino’s allegories were supposed to be puzzling. A visual equivalent of the intellectual poetry which was popular at the time, this is a feast for the mind a well as the eyes.

6. Bronzino the Intellectual

Like many artists during the Italian Renaissance, Bronzino considered himself more than just a painter. He wrote poetry and associated with the intellectuals of the day. Laura Battiferri, a close friend, was herself a poet and intellectual, a member of the Medici court, married to the sculptor Bartolomeo Ammannati.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Laura Battiferri, 1550–1555, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy.

Bronzino represents her in sharp profile against a plain background, in the style of a 15th-century portrait. Dressed in sombre colors, with a demure high neck and half-veil, she is clearly a woman who wants to be taken seriously. An open book in her hand reveals Petrarch‘s sonnets, associating her with the great 14th-century Italian poet. More specifically, the verses that are visible were written by Petrarch to his unrequited love and muse, Laura.

The Mannerist elongation is still obvious in her neck, fingers, and angular facial features. The aloofness and lack of engagement can here be read as Battiferri’s intellectualism. However, the painting also shows Bronzino’s own subtlety and cleverness. He is paying tribute to his friend, whilst at the same time touting his own credentials as part of a long intellectual and artistic tradition.

7. Bronzino’s Humor

Bronzino also wrote bawdy, humorous verse and his double portrait of Nano Morgante might be seen as a pictorial joke. Morgante, real name Braccio di Bartolo, was a dwarf jester at the Medici court, employed at a time when that was considered amusing. His nickname referenced a giant in a popular poem.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of the Dwarf Nano Morgante (view of both sides), 1553, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Bronzino painted a double-sided portrait of him, incongruously nude whilst hunting for birds. From the front, we see him holding an owl, two butterflies strategically and comically placed. The pygmy owl references Morgante’s stature; butterflies symbolize the Fool on tarot cards. On the back of the painting, he is seen from behind, having caught a bird.

The painting had a serious purpose. There was an ongoing contemporary debate, known as the paragone, about which of the arts was superior. Bronzino was aiming to prove that painting could show someone in the round just as effectively as sculpture. However, he chooses to do it with a painting which undermines the ideal of the classical nude. Today, it seems an exploitative image, but at the time, Bronzino was making fun of artistic tradition as much as of Morgante himself.

8. Mannerist Mystery

Many of the themes of Bronzino’s art come together in this painting of Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus. It is an allegory and a portrait, both intellectual and humorous. Above all, it is a mystery. Recognisably a portrait of Cosimo, it nonetheless seems surprising that he would want to be represented nude, as Orpheus, the Greek hero who entered the Underworld to find his wife Eurydice.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus, c. 1537–1539, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Bronzino produced a similar subject, showing the famous mercenary Andrea Doria as Neptune, but it is more obvious that an admiral would want to be represented as the sea god. Cosimo’s painting is dated from around the time of his marriage: it could be a celebration of love, but it is an odd one, considering that it ends in tragedy (Orpheus disobeys the gods, looks back, and loses Eurydice forever).

The minimal background shows the three-headed dog, Cerberus, which Orpheus pacified by playing music. The painting could therefore symbolize how Cosimo would be a calming influence on the politics of Florence. However, Cosimo/Orpheus holds a stringed instrument in one hand and the bow, oddly angled between his legs, in the other. The innuendo is clear and a bow was a recognized contemporary phallic euphemism. The painting was therefore perhaps commissioned to undermine the young Duke rather than celebrate him.

9. Bronzino’s Sexuality

Another ongoing mystery centers on Bronzino’s sexuality. Like many Renaissance artists, he seems to have had romantic, if not sexual, feelings for young men, and he is known to have lived with his adopted son and pupil Alessandro Allori for the last 20 years of his life. Homosexuality was, however, severely punished at the time.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of a Young Man, c. 1550–1555, National Gallery, London, UK.

Bronzino’s poetry contains veiled homoerotic references, and he did paint a number of portraits of, now anonymous, young men. However, it is the way he painted them—elegant, sensual—which has attracted comment: as early as the 19th century, J. A. Symonds wrote of the “personal corruption” of his style.

Portrait of a Young Man presents us with someone who appears to be a serious scholar: dressed soberly, he has a book in front of him and a slight frown as he looks out towards us. All this is undermined by background in which a sensuously painted pink curtain is drawn back to reveal Bacchus, god of wine and frivolity. Bacchus had famously been sculpted by Michelangelo, in a way which Vasari described as having “both the slenderness of a young man and the fleshiness and roundness of a woman.” Is this the man’s hidden self?

10. Mannerist to the End

By the end of Bronzino’s career, the world was changing. Particularly, the church was looking for art that represented serious piety in a straightforward way. Mannerism was becoming old-fashioned. One of Bronzino’s last works, however, was arguably his greatest contribution to the style.

Agnolo Bronzino, Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, 1569, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy.

Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence is an explosion of largely nude figures in a grandiose architectural setting. It looks more like a party than a gruesome death and Lawrence himself reclines elegantly as he is roasted alive in a pose which deliberately mirrors Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. On the left, standing under a statue, Bronzino has included a rare self-portrait, alongside Pontormo and Allori.

It is a crazy, impressive, technically brilliant painting. Bronzino is showcasing his talents but also trumpeting the magnificent absurdity of Mannerism. It was a movement that did not play by the rules, which could be clever and funny, and which never forgot that art was about creating, not imitating reality. And Bronzino was one of the greatest Mannerists of them all.