Summary

- Learn about a powerful figure in the Medici court: Eleanor of Toledo. The Duchess’ portrait by a Mannerist painter, Agnolo Bronzino, carries a strong message of political power, motherhood, fashion and heritage.

Who Was She?

Eleanor of Toledo (1522–1562) was the second daughter of Don Pedro of Toledo, Marquis of Vilafranca and a member of the prominent Alba family. A Spanish noblewoman, she became Duchess of Florence by marrying Cosimo I de Medici in 1539. Born in Spain, she moved to Italy at 11 years old due to her father being the viceroy of Spain in Naples. In the lavish Neapolitan environment, Eleanor was presented with extravagance, rank, and prestige. In this context, she learned essential lessons for her future as a regent.

Agnolo Bronzino, Eleanor of Toledo, 1543, Národní Galerie, Prague, Czech Republic. Web Gallery of Art.

A Marriage of Love & Convenience

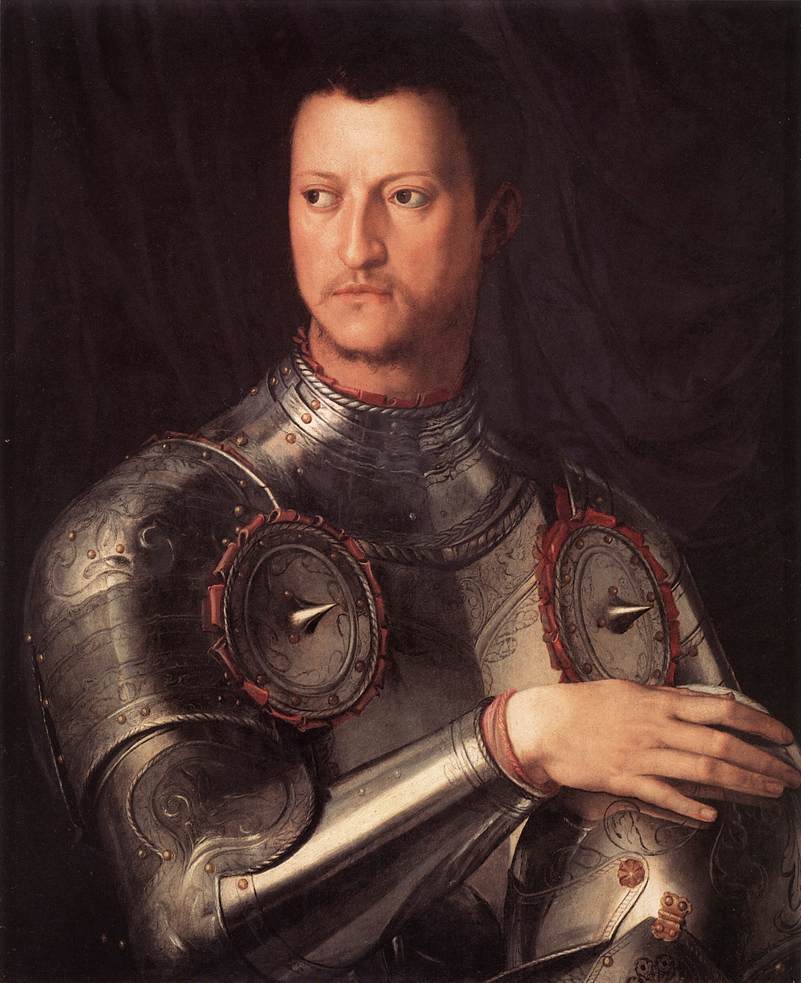

Cosimo I de Medici (1519–1574) could have married the viceroy’s eldest daughter – and it was actually expected of him to do so. But it was Eleanor he wished to marry. Remembering her beauty from when they first met, Cosimo insisted on having her as his wife. It is said that he remained faithful throughout their entire marriage (and this was a time when a husband having mistresses was not at all unusual).

The Medici-Toledo union may have been a love match, but it was also a very strategic choice for the Duke of Florence. Eleanor’s father, Don Pedro, not only had great authority in Italy but also had close relations with Emperor Charles V. Through this marriage, Cosimo I de Medici secured an important connection to both Austrian and Spanish houses.

Agnolo Bronzino, Cosimo I de’ Medici in Armour, 1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Web Gallery of Art.

The Duchess of Florence

Eleanor of Toledo was the Duke’s constant companion. She not only fulfilled the roles expected of her as a wife and a mother but was also an active part of her husband’s duties. The Duchess acted as his regent when he was taken ill and, during his absences, she would be included in the direction of military affairs. Eleanor and Cosimo were seen as joint rulers.

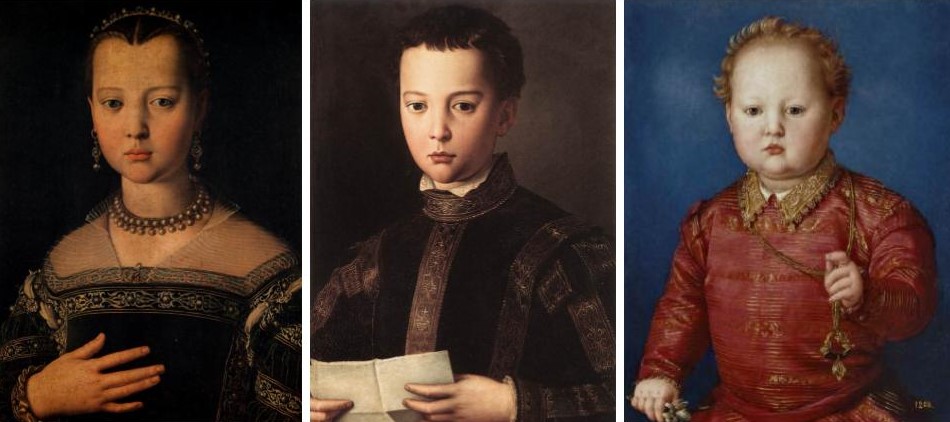

An intelligent young woman, she had a considerable pedigree and her own personal wealth. On top of being an active regent, she was a mother to 11 children – and her importance at the time relied heavily on the many children she had. The Duchess’ fertility was seen as the security of the Medici dynasty and, as a consequence, the future of Florence.

Left: Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Maria de’ Medici, 1551, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Web Gallery of Art. Center: Portrait of Francesco I de’ Medici, 1551, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Web Gallery of Art. Right: Don Garcia de’ Medici, c. 1550, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Web Gallery of Art.

Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with Her Son Giovanni

This state portrait was painted by Agnolo Bronzino, a Mannerist painter who was one of the leading portraitists of his time and also a court painter of the Medici family. The artist’s challenge here was to devise and represent Eleanor of Toledo’s image as regent. The composition presents Eleanor of Toledo at age 23 and her second son, Giovanni, at two years old. Mother and son are side-by-side in front of a landscape and a dark blue sky.

The Duchess is portrayed in a three-quarter-length pose and occupies most of the frame. She is slightly turned to her right, the same side on which her infant son stands. The mother is richly dressed and bejeweled, and the boy’s clothes are also expensive – even if less extravagant. Giovanni’s clothing is close in color to the background, making him nearly blend in with it. The viewer’s attention is maintained on Eleanor – or better, on her dress.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture.

Cold, Aloof, or Bored?

The portrait presents a highly-idealized Eleanor. Her face is a perfect blemishless oval, her skin is so smooth and pale that it almost doesn’t look like skin. Both her and the boy’s faces have a marble-like quality to them. Posing with a stiff posture, the regent’s expression is removed and serene.

Some say she is looking down on us (in an arrogant way), while others think she looks plain bored. This coldness and aloofness perceived in her expression are typical of court portraiture. Bronzino’s portraits have even been described as “icy” due to the distance perceived between the subjects and the viewer.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail.

Mannerists were fascinated by the idea of masks because they liked the concept of presenting something meant to be seen while hiding something else underneath. Masks were included in many different ways in Mannerist paintings (some more obvious than others). Eleanor and Giovanni’s expressions are like masks, like a shell of something more real. They don’t reveal much of what’s underneath – their thoughts or feelings. You can see the difference between Giovanni’s expression here and his smile in another portrait by Bronzino. Beside his mother, he is not portrayed as a chubby smiling baby, but as an heir.

Left: Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Detail. Right: Portrait of Giovanni de’ Medici as a Child, 1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Web Gallery of Art.

Mother and Son

The presence of the Duchess’ son in this painting is essential to her image. Her authority as a regent does not downplay her role as a mother, which was seen as of the highest importance. As a woman, her wifely duties and values – such as modesty, chastity, and fertility – must be highlighted. Here a young, powerful, and rich mother in her prime is presented.

The only interaction between the two figures is indicated by Eleanor’s right hand laying on the boy’s shoulder and his left hand softly touching his mother’s gown. Although much less warm and intimate than what had been seen in the High Renaissance, mother and son in a triangular composition evoke the idea of Madonna and Child.

By doing so, the portrait attests to the sanctity of the regent and her role. The painting flaunts and assures her fertility and the future of the Medici dynasty. The shade of the background is even lighter around the Duchess, especially her head, giving the impression of a “halo.”

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail (edited).

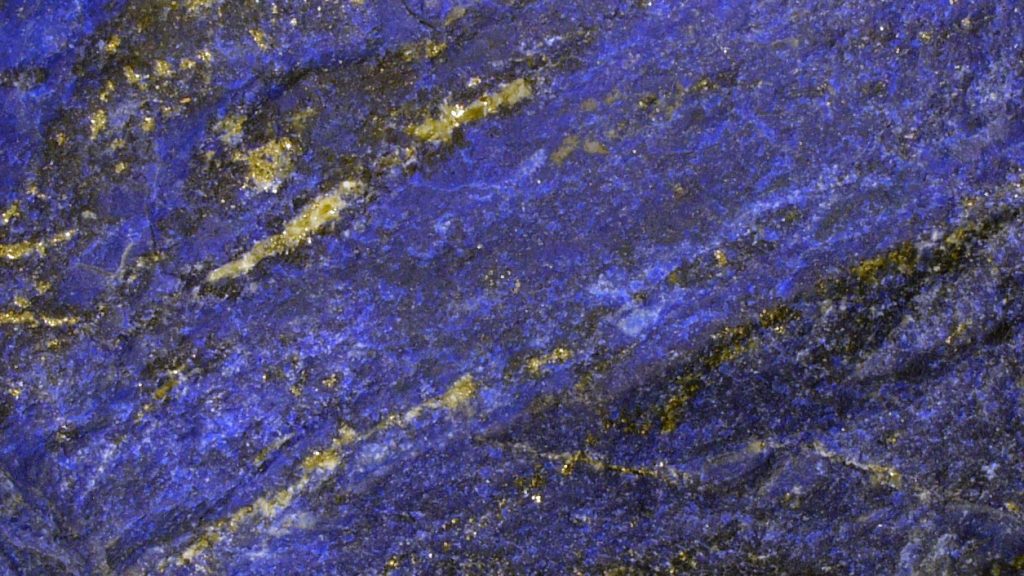

Signaling Wealth

The background is predominantly blue, like the deep dark sky. The dark blue comes from the precious (and very expensive) lapis lazuli. This pigment was associated with exclusiveness and divinity. Since it was highly pricey, its use indicated the wealth of being able to afford it. The more saturated and pigmented it was, the more it cost. The background of this portrait required great quantities of lapis lazuli: Bronzino said he could not do with less of it.

The materials used, such as gold and rare pigments, said much about the value of a painting. But at some point during the Renaissance, the appreciation of the intrinsic value of a painting’s materials had been shifted to the appraisal of the artist’s skill. It wasn’t really one or another, but a combination of both.

A slab of lapis lazuli in its raw form. Photo by Hannes Grobe via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.5). Detail.

So what makes this painting valuable is not only the lapis lazuli used for the background or the gold used for the dress but also Bronzino’s work and the time he spent on it. The dress’ brocade, in particular, was very time-consuming to reproduce. That increased the cost of the painting’s execution and, by that, the ostentation of its production. To Bronzino, each and every spot of a painting had to be accounted for – he even mocked painters who worked too quickly.

Dress to Impress

Eleanor of Toledo was highly aware of the importance her clothes held. She saw it as a duty to express her rank through her clothing. Her aristocratic upbringing in Naples resulted in a love for luxury – which, thanks to her wealth, she was able to indulge. In this portrait, her dress is actually the focus of the composition (it almost overshadows the portrayed figures).

She loved this dress, it is said; she wore it often. The dress was so memorable that for years it was believed that the Duchess was buried in it. It was only a rumor, though, and her actual funeral dress (or the remains of it) can be seen today in the Museum of Costume and Fashion, in Florence.

Eleanor of Toledo’s funeral gown, Museum of Costume and Fashion, Florence, Italy. The Closet Historian.

The Duchess’ hair is center-parted and pulled back in a way that no strands layout in place. She wears a gold and pearl hairnet that echoes the design of the garment covering her neck and shoulders (called a partlet). Eleanor’s dress is undeniably sumptuous with its intricate brocade and raised patterns in black and gold. The bodice of the gown is rigid and square-necked. Pearls appear not only on her hairnet and partlet, but she also wears two large pearl necklaces and pearl drop earrings.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail.

In addition to its beauty, the dress holds layers of meaning. A large part of her dowry was constituted by Spanish textiles, so the gown serves as a symbol of her fortune and of the treasures she brought to Florence. Adding to that, sumptuousness was a crucial element for state portraiture. The size of her many jewels and the complex brocade in her dress signal her wealth. Such an intricate motif and its gold-bound threads were not cheap and not accessible to many. The raised pattern is created by a type of brocading called space weaving. The effect is obtained by additional threads being brought into the fabric on small shuttles. These threads were often of valuable materials like gold and silver.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail.

Bronzino depicted in detail the rich brocade, and the artist’s mastery to render the texture and the details of the clothing are impressive. Giorgio Vasari, artist and biographer of the Italian Renaissance, suggested that representing these sumptuous textures in such a meticulous way was intended to awe the public. After all, embroidered and brocade motifs denoted rank and brought attention to the exclusiveness of the court.

The sumptuous dress not only affirms Eleanor’s rank but also marks her as exempt from the sumptuary laws of Florence. These laws restrained excessive luxury such as cloths of gold and targeted especially women’s clothing.

The Pomegranate Motif

Authority, virtue, political influence, and much more could be signaled by subliminal meanings in brocades, designs, and motifs. The golden brocade located in the center of the Duchess’ torso is called a pomegranate motif: a stylized design of a central floral image surrounded by wavy stems. It is key to Bronzino’s composition for a couple of reasons. First of all, it draws the viewer’s eyes due to its quite central position. The motif serves as a commanding focus on Eleanor’s dress.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail.

Besides that, the pomegranate was considered a symbol of marriage and fertility. The fruit had been especially associated with Eleanor due to her role as the mother of a new generation of the Medicis. But this motif might also carry the subliminal message of access to imperial power. The brocade is probably of Spanish design, and the pomegranate had its own meaning throughout the Habsburg Empire. The fruit’s many seeds signified unity under one authority. It is possible, then, that the pomegranate motif on the dress’ bodice claimed imperial patronage and favor.

An Image of Power and Authority

The power and dominion that exude from the painting do not come from obvious objects such as a crown or armor. There is no specific reference to the regent’s authority – that is shown through her wealth and decorum. The underlying power is found in her stiff posture, idealized features, detached yet serene expression, and luxurious garment.

In a subtle way, even the landscape in the background adds to this idea. The expense of land is most likely an allusion to Florentine dominion. Unlike other portraits, she is not confined by any walls, but visually expresses her regency on the broad landscape (an uninterrupted view).

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, 1544–1545, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. Google Arts & Culture. Detail.

Contemporary opinions on Eleanor as a person are much varied and contradictory. According to different sources, she is said to be both a “barbaric Spanish woman” and a “perfect adoptive Florentine”. While some said she was haughty and arrogant, others called her benevolent and a caring mother.

This painting cannot be seen as a reliable representation of the “real” Duchess either. It is a highly-curated portrait that intentionally built her official image as a regent and a mother. Replete with indications of wealth and underlying power, it was copied multiple times and disseminated to claim her regency. A reserved yet elegant portrait, it eulogized Eleanor of Toledo as the mother of a new Medici dynasty and a capable ruler.