5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

To the general public, the Italian Renaissance is the pinnacle of art history. More than 500 years on, it’s still the subject of blockbuster exhibitions and record auction prices all over the world. Many people consider this period to represent the gold standard of artistic and cultural achievement. But what exactly was the Italian Renaissance, and why is it so special?

The Renaissance started in Italy, specifically in the intellectual center of Florence. Then, it spread throughout western Europe in various forms. After earlier precursors, the Italian Reniassance properly began in the 15th century and reached its apex in the first half of the 16th century.

More than just an artistic style, the Italian Renaissance encompassed philosophy, literature, religion, science, politics, and more. At the heart of it all was humanism, a philosophy celebrating human intellect and creativity. This way of thinking strongly contrasted with medieval philosophy, which centered on the divine and minimized human agency. Humanism empowered Renaissance thinkers to reach new heights of intellectual and artistic achievement. It fostered widespread learning and scientific inquiry. The legacy of humanism has strongly influenced the Euro-American world ever since.

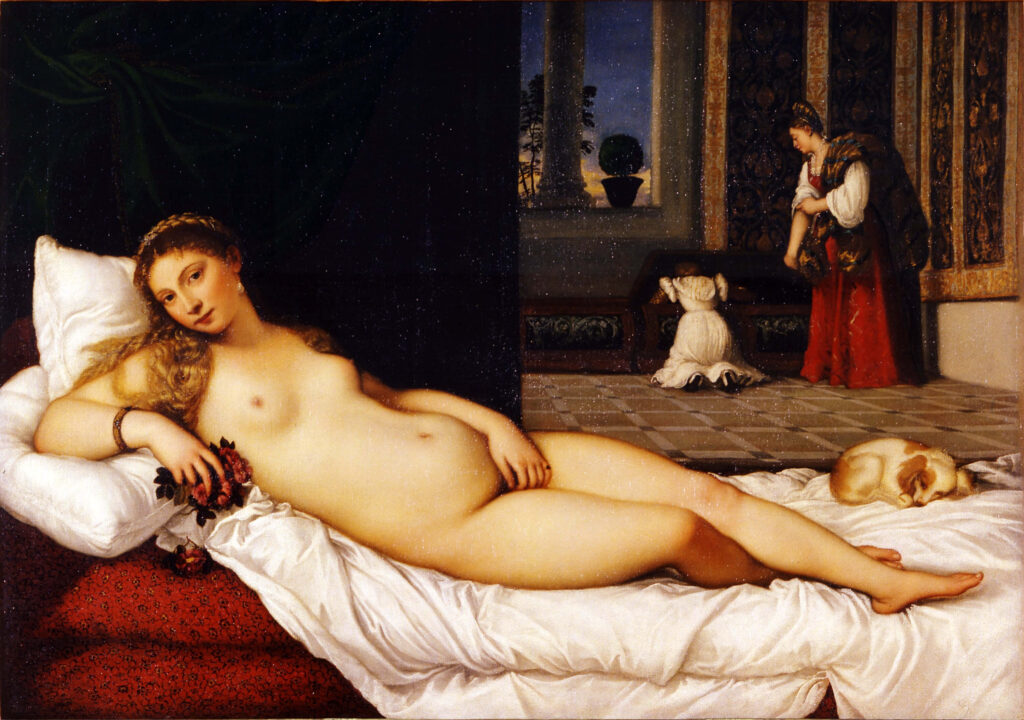

Thanks to humanism, Renaissance-era Italians began to once again appreciate their classical Greek and Roman heritage in all its forms. The word “Renaissance” means rebirth – in this case, the rebirth of the antique tradition. While the Italian Renaissance was still a deeply religious era, people became more comfortable with the idea that the pagan classical past could coexist with Christianity. As their countrymen embraced the classical past, Italian artists closely studied the classical statues being excavated in Rome. Classical myth and history became popular subject matter for Renaissance artists, as can be seen in Raphael’s The School of Athens.

If you like ancient Greek and Roman artwork, Italian Renaissance art may look very familiar to you. That’s because Renaissance artists often incorporated poses and compositions from classical artwork into their own pieces. Renaissance intellectuals believed that the ancients had already created the perfect solutions to all problems, so quoting from the classical masters was a popular strategy.

Such visual and literary quotations could be quite sophisticated, and some were legible only by the educated. This complex symbolism and subject matter helped raise artists’ status from mere craftsman to respected intellectuals.

As Italian Renaissance society became more scientifically inclined, artists sought to depict the world with greater naturalism. Naturalistic art represents its subjects in a way that accurately reflects their real-life appearances. At its best, it can produce the convincing illusion of reality. Naturalism was a prime goal of Italian Renaissance art, just as it had been in classical Greece and Rome. The high degree of naturalism seen in High Renaissance masterpieces is undoubtedly the period’s greatest hallmark.

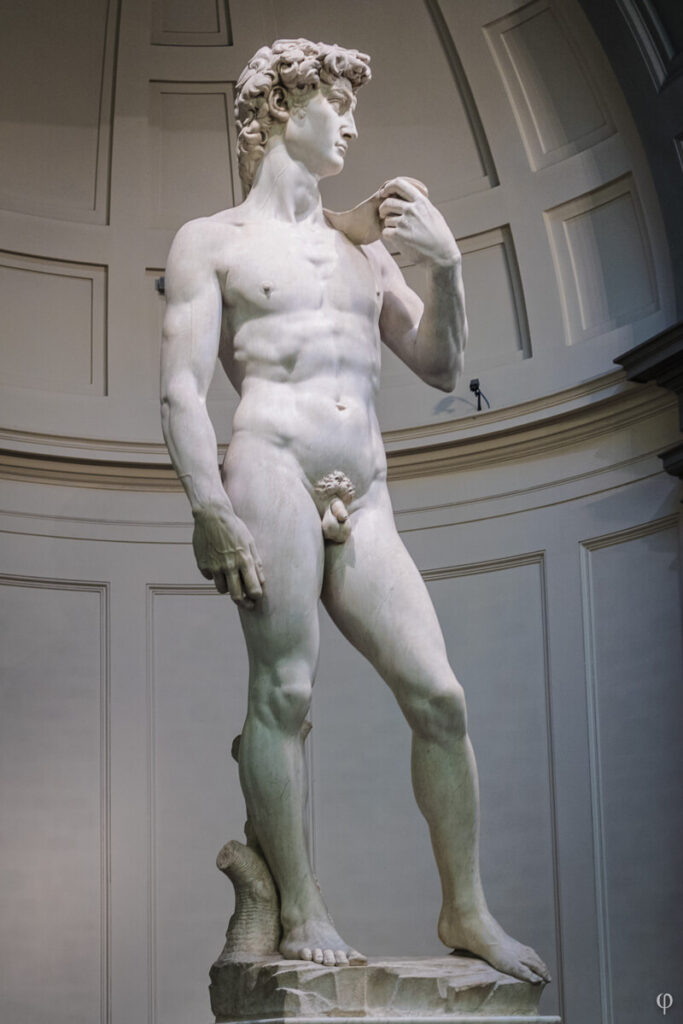

Renaissance artwork features anatomically-accurate human figures for the first time since antiquity. Artists studied anatomy by sketching from nude models. Some went as far as to secretly dissect cadavers to further their anatomical understanding. With this knowledge, Renaissance artists could portray figures in complex, dynamic, and technically-demanding poses, such as contrapposto. Like the ancients, they loved to render the nude male figure in all the details of its musculature. Painters created believably three-dimensional forms, human and otherwise, by modeling them in lights and darks. This technique, sometimes called chiaroscuro, mimics the way that light plays on masses in the real world. Sculptures like Michelangelo’s David also became less frontal in their poses and more three-dimensional in their modelling.

It wasn’t just forms that become more lifelike, however. Artists pursued emotional as well as aesthetic truth, with eloquently expressive results that likely account for Italian Renaissance art’s continued popularity across the centuries.

Filippo Brunellesci’s concept of linear or one-point perspective allowed artists to convey a naturalistic sense of three-dimensional space throughout their entire compositions. Linear perspective involves creating a series of diagonal lines (orthogonals) that all meet at a single vanishing point at the horizon. This idea reproduces the real-life way that parallel lines seem to meet up as they recede into the distance. The result of these converging orthogonals is a two-dimensional image that gives the illusion of three-dimensional space. It’s unclear whether classical artists used a similar strategy, or if linear perspective truly was a Renaissance innovation.

During the Proto Renaissance, artists such as Duccio, Cimabue, and Giotto started to move away from medieval-style flat or “decorative” figures on gold backgrounds, slowly adding volume, depth, and emotion to their paintings. This pre-Renaissance phase took place in the 13th and 14th centuries, when the rest of Europe was still firmly in the Middle Ages. Proto Renaissance paintings may still look naive to modern viewers.

The Renaissance properly began in the 15th century. This period saw the development of techniques linear perspective. Artists of the Early Renaissance included Donatello, Masaccio, and Fra Filippo Lippi. Early Renaissance art convey an attractive, believable sense of naturalism but perhaps lacks some of the dynamism of later Renaissance masterpieces.

The world-famous trio of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael worked during the High Renaissance. The first half of the 16th century saw the creation of artworks embodying Renaissance ideals on the highest possible level. High Renaissance paintings and sculptures feature beautifully modeled human bodies in complex poses, dramatic and emotional compositions, deeply naturalistic depictions of space, and intellectually sophisticated subject matter.

In the middle decades of the 16th century, Mannerism overlapped in time with the High Renaissance; however, it took things in a different direction. Instead of aiming for strict naturalism, Mannerists showed off their skills by intentionally exaggerating and distorting their images. Parmigianino’s dramatically elongated Madonna of the Long Neck in a textbook example of Mannerism.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!