Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

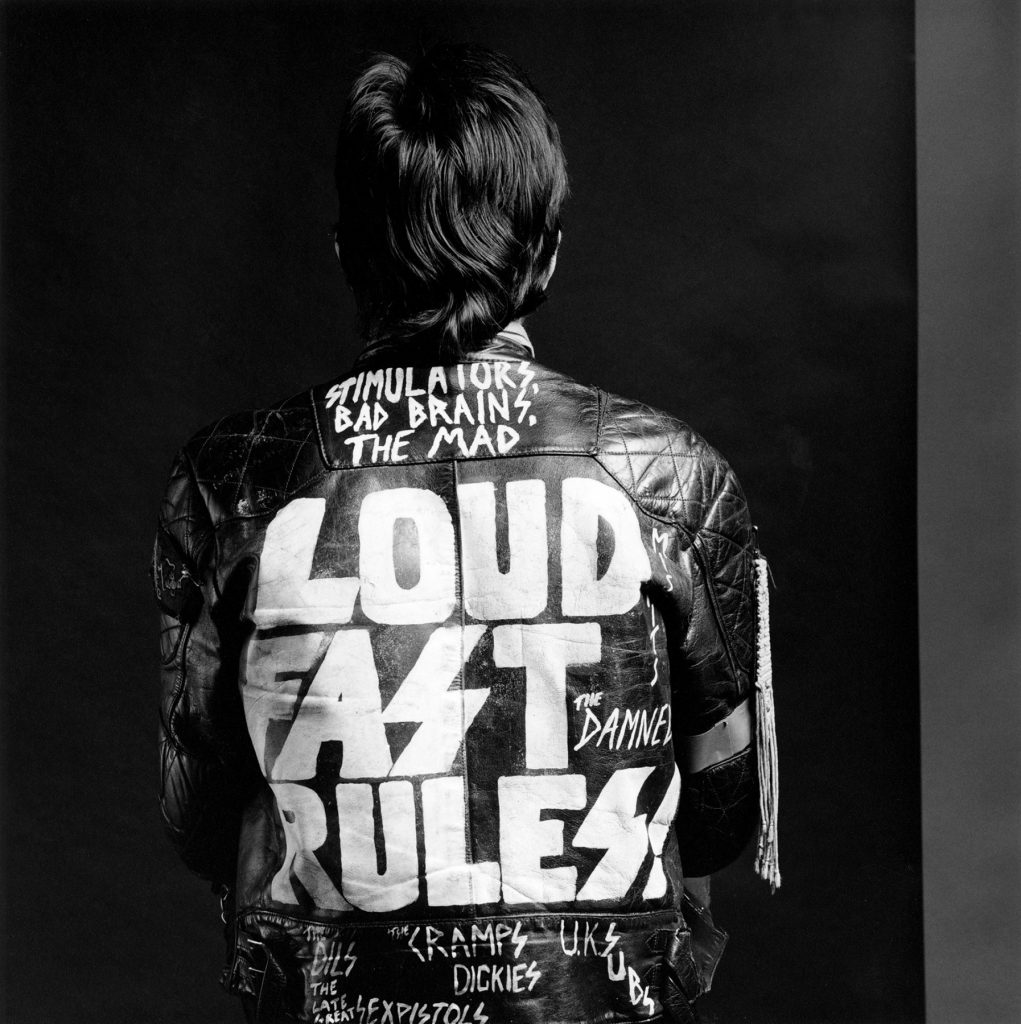

Controversial photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989) shocked the world with his images of bondage, gay-sex, female bodybuilders, and naked black men. Always technically brilliant, sometimes politically problematic, these photographs captured a New York community during times of intense social change.

Mapplethorpe was an artist whose work became completely bound up with the times in which he lived. He captured moments in time that will be forever remembered; while street photography ruled, he retreated back to the studio, producing tightly composed, black and white portraits, still lives, and erotic art.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Nick Marden, 1980, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

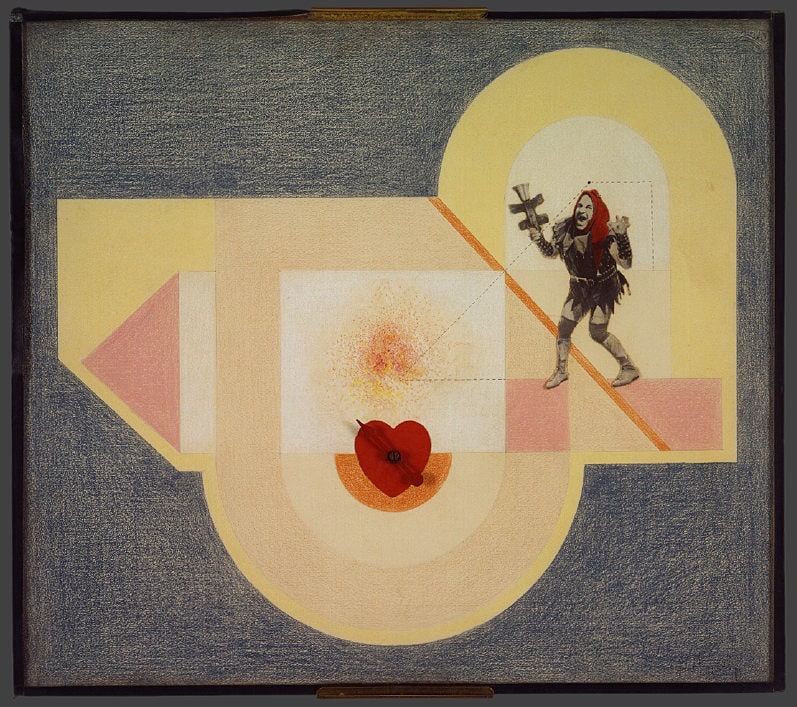

At 16 years of age Mapplethorpe started to experiment with art and in 1963 he enrolled at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, where he studied drawing, painting, and sculpture. He was influenced by artists such as Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, and he experimented with various materials in mixed-media collages, including images cut from books and magazines. He acquired a Polaroid camera in 1970 and began producing his own photographs to incorporate into the collages.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Untitled, 1968, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

The image above shows how Mapplethorpe started as an artist. There are clear surrealist influences here. The framing of the work is very ‘Mapplethorpe’ even at this stage. In his later photographs images are tightly controlled and ‘framed’, drawing your attention not only to what you see but also to what you don’t see.

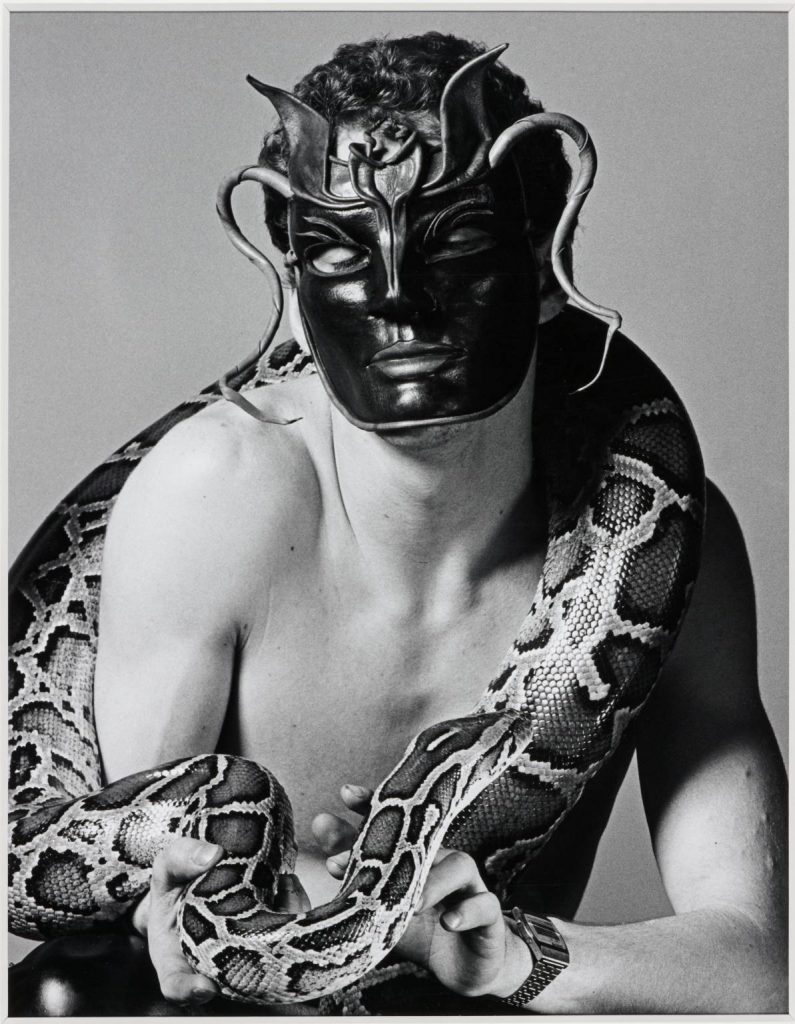

Robert Mapplethorpe, Snake Man, 1981, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Mapplethorpe’s work is especially about the time and the place he inhabited: New York from 1960 to the 1980s. He grew up as a catholic, but he was quite the social radical. It was a time of intense political activism in the USA: the civil rights movement, anti-Vietnam War protests, feminism, and gay rights (including the Stonewall Riots). This was a time of culture wars and censorship. Galleries were considering what they would (and would not) show in public spaces.

The whole point of being an artist is to learn about yourself. The photographs, I think, are less important than the life that one is leading.

Ted Stansfield, Another Man magazine, 27 Oct, 2017.

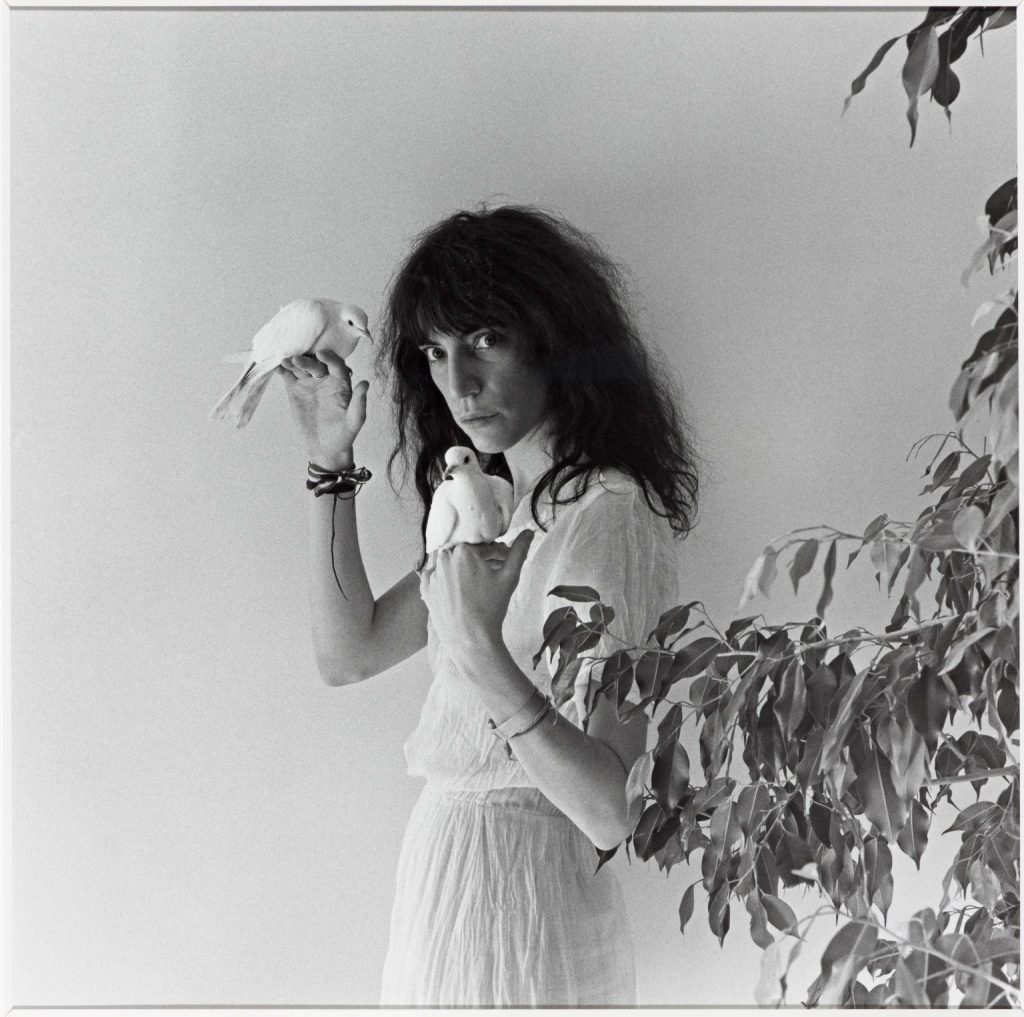

Robert Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith, 1979, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

In 1967, musician and poet Patti Smith moved to New York City from South Jersey, and the rest is rock and roll history. Smith became Mapplethorpe’s lover, soulmate, and collaborator. Even after Smith married, their friendship continued. Together they produced legendary black and white portraits. In 1970, they moved into the glamorous poverty of the iconic Chelsea Hotel in New York. Patti Smith is a poet, an artist, and a rock star, and it was in her friendship with Mapplethorpe that her legend began.

Robert took areas of dark human consent and made them into art. He worked without apology, investing the homosexual with grandeur, masculinity, and enviable nobility. Without affectation, he created a presence that was wholly male without sacrificing feminine grace.

Just Kids, Ecco Press, 2010.

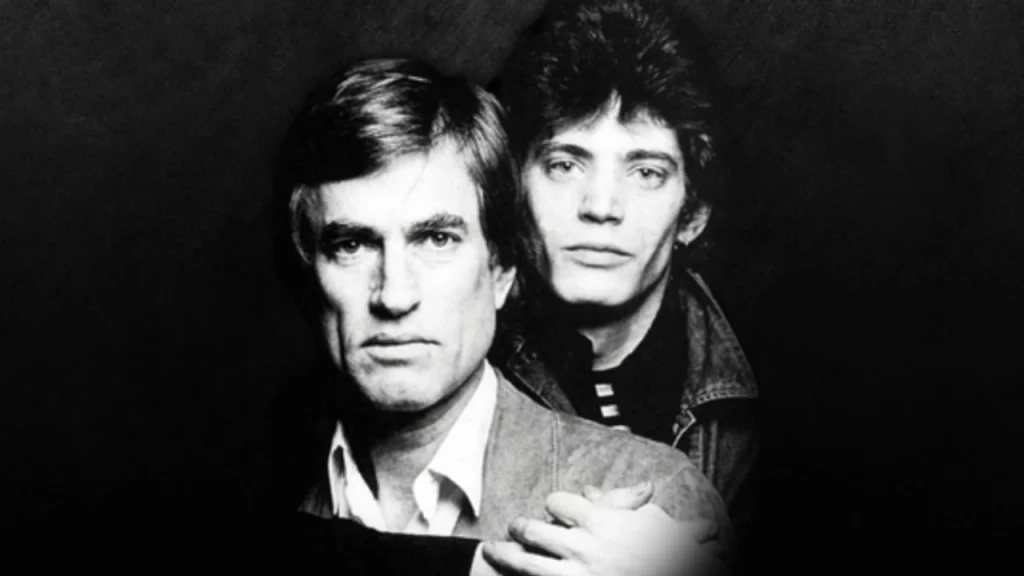

Film still from Black White + Gray A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe (2007) directed by James Crump. Tribeca.

Samuel Jones Wagstaff Jr. was an American art curator and collector, as well as the artistic mentor and benefactor of Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith. A supporter of Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art, he was drawn to Mapplethorpe’s photography and championed it as fine art. Wagstaff became Mapplethorpe’s lover and lifetime companion. Mapplethorpe has become so well known as to overshadow other artists of the time, such as Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz, who both died of AIDS-related causes and explored similar subject matter in their art.

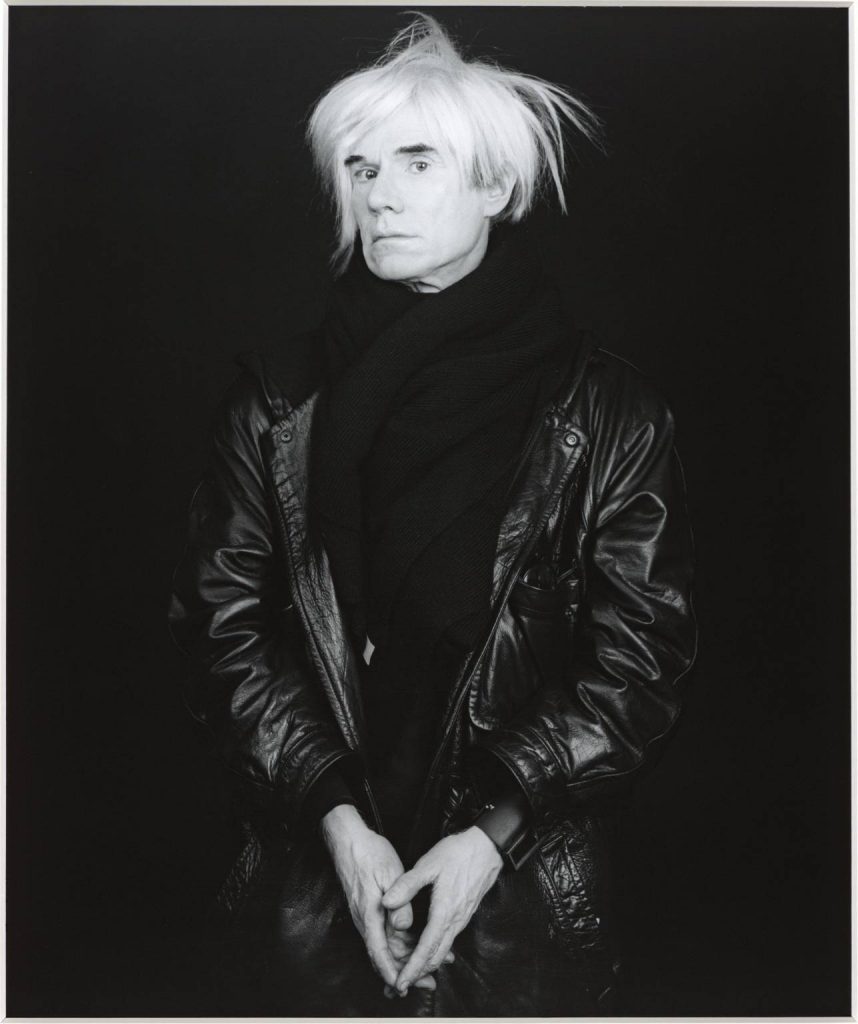

Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, 1986, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Although Mapplethorpe took his first photographs using an instant Polaroid camera, he soon acquired a Hasselblad medium-format camera and began taking photographs of a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, including artists, composers, and socialites. His portraits included Willem de Kooning, Alice Neel, Roy Lichtenstein, Louise Bourgeois, Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry, and David Hockney. These images are true portraits, in the art canon. They are all staged studio shots, with long exposures, and sharp black/white contrasts. It is said that Mapplethorpe worked slowly and was a perfectionist.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait, 1975, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York, USA

Experimentation was always key to Mapplethorpe’s work. In Self Portrait, 1975, shown above, notice how Mapplethorpe is tightly controlling what you see. Three-quarters of the face, tucked in the top right corner; one arm; part of the torso. And of course, there is controlled studio light and shadows. The effect is one of a contained, triangulated image, which is also humorous. A whole series of self-portraits show him using photography to explore his self-image. As with many previous artists (Rembrandt for instance), the artist himself is his most available model.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait, 1980, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Mapplethorpe was very much influenced by 19th-century portraiture by photographers like Julia Cameron and Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (known as Nadar). Julia Margaret Cameron (née Pattle) was a British photographer who became known for her portraits of celebrities of the time, and for photographs with Arthurian and other legendary or heroic themes. Another strong influence on Mapplethorpe was Edward Henry Weston. Over the course of his 40-year career, Weston photographed still lifes, nudes, portraits, and genre scenes.

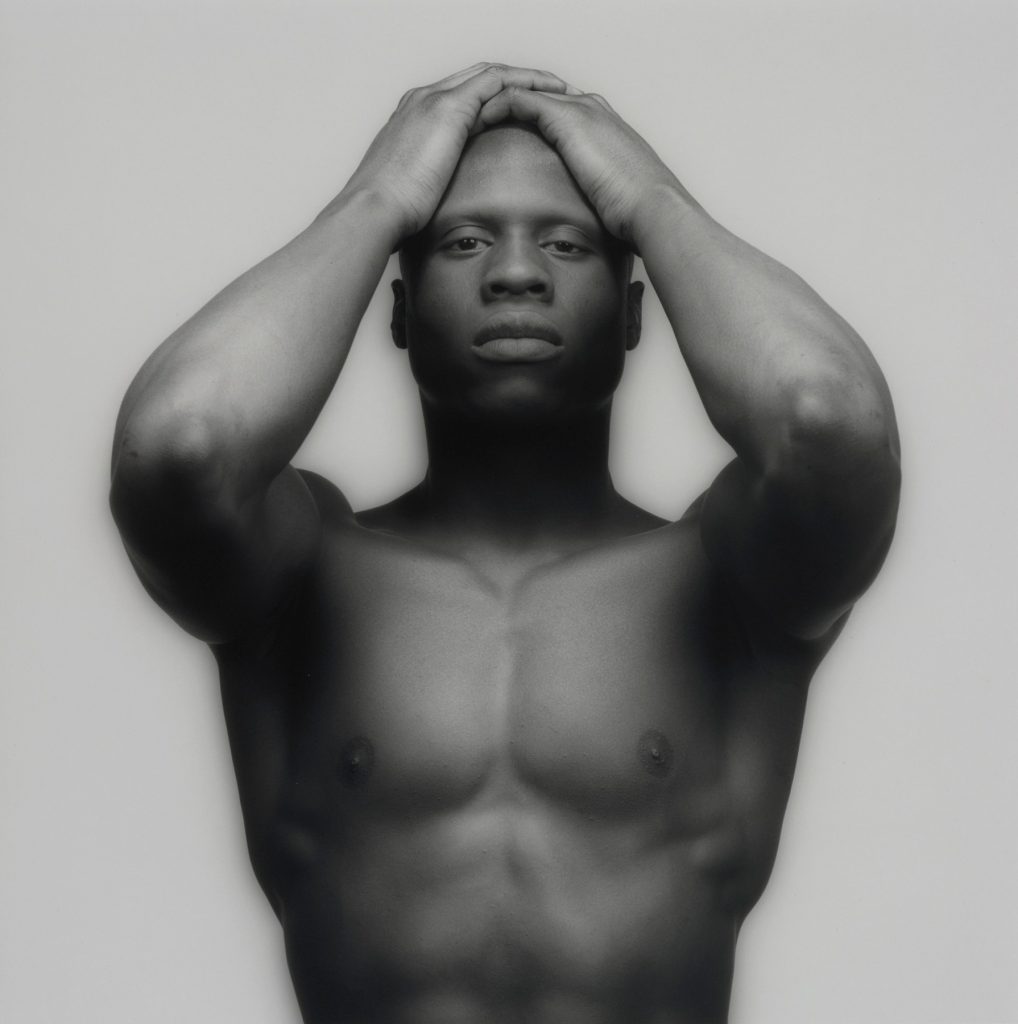

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ken Moody, 1984, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

The 1986 solo exhibition Black Males and the subsequent book The Black Book sparked controversy over Mapplethorpe’s depiction of black men as sexual subjects. The work was largely phallocentric and sculptural, focusing on segments of the subject’s bodies. Mapplethorpe said his intention was the pursuit of the “Platonic Ideal”, but the images (potent and erotic depictions of Black men) were widely criticized for being exploitative, with their subjects extremely fetishized. Ken Moody was perhaps Mapplethorpe’s most photographed male model. A graduate of the Fashion Institute of Technology and a professional fitness instructor, he said he was not “ghetto enough” for Mapplethorpe.

We didn’t necessarily like each other. I don’t think that he liked me, nor did I like him. We had nothing in common. Nothing. And I was always suspicious of people who were driven by sex. Robert fetishized Black men. He objectified them. I knew what his tastes were, and I also knew that I was not that.

Ted Stansfield, Another Man magazine, 27 Oct, 2017.

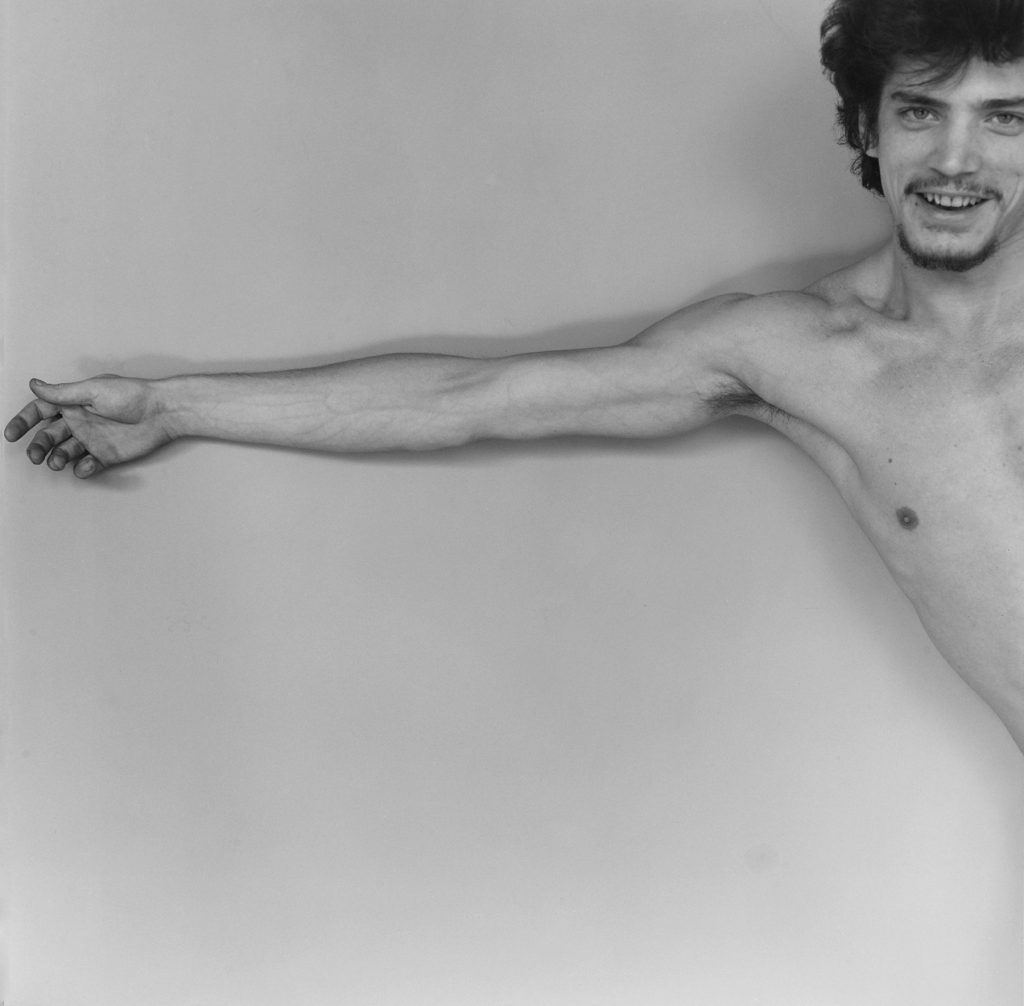

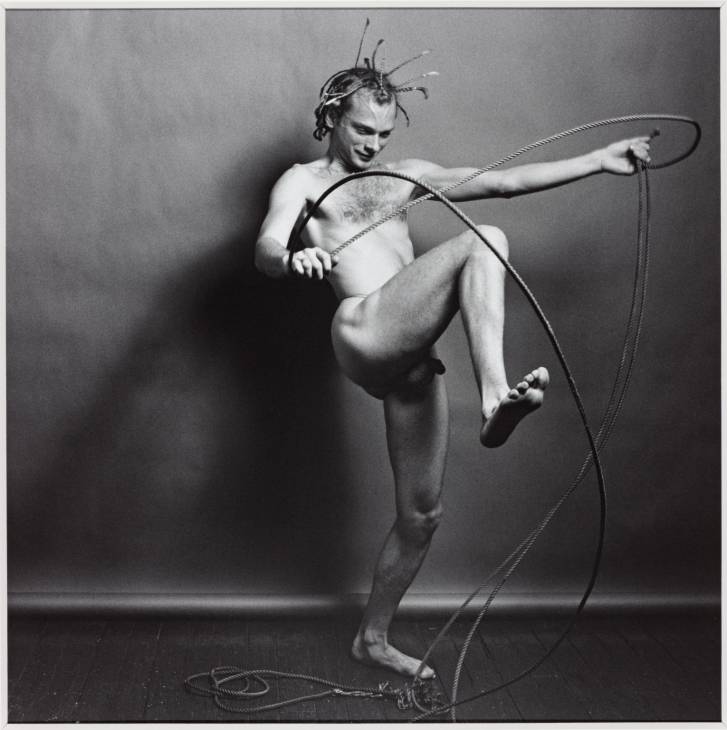

Robert Mapplethorpe, Alan Lynes, 1979, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Alan Lynes was a dancer with the Peter Reed Ballet Company. Tate London and National Galleries Scotland jointly own this image, and describe it as looking like a dancing satyr, wondering if this man may be using rope for bondage or dancing. The references to ancient Greek mythology are obvious here—Mapplethorpe had a keen interest in classical art, which influenced many of his nudes. He also collected ceramics, and this image mirrors the figures, curves, and arabesques of a classical vase.

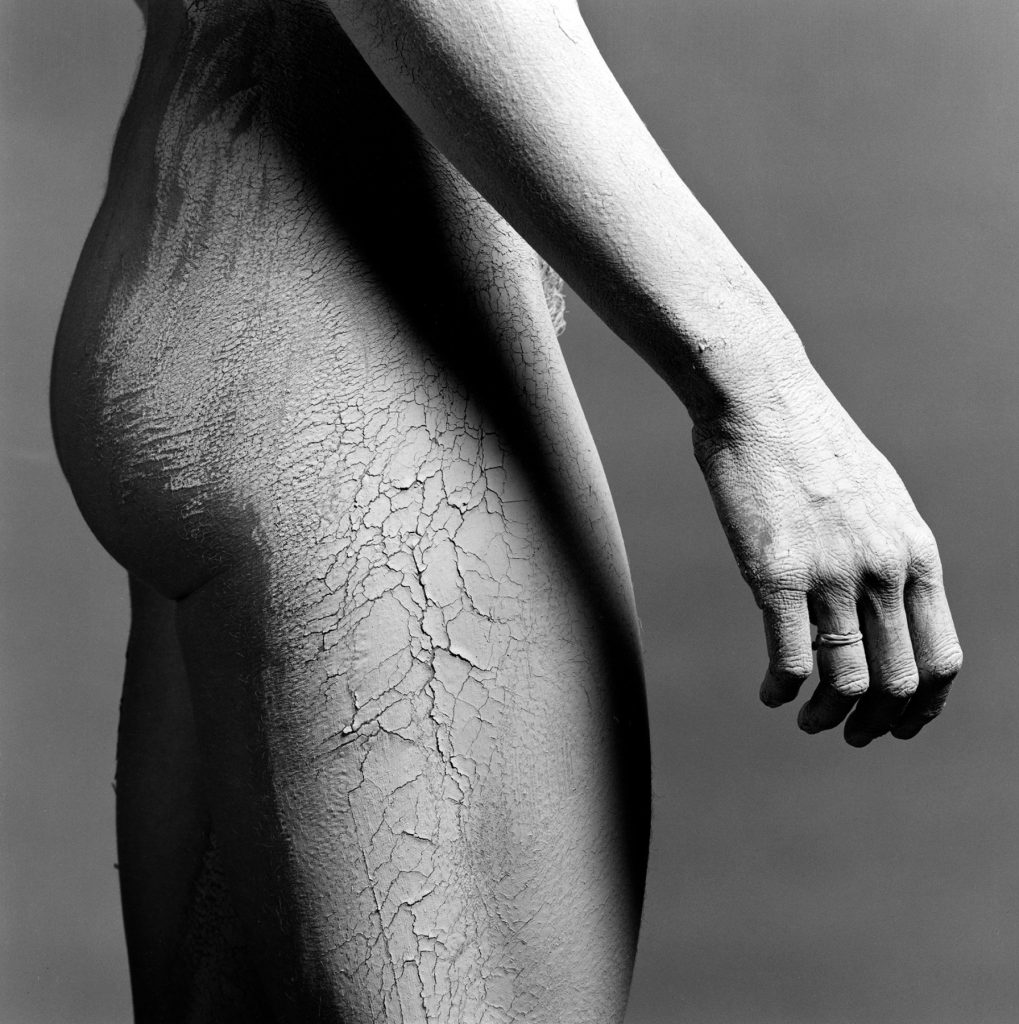

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1982, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Mapplethorpe was obsessed with sculptural images. Sculpture is key to his work and his interest was always in 3-dimensional forms. He greatly admired the work of Michelangelo. Lisa Lyon was the world’s first female bodybuilder. She became something of a muse to Mapplethorpe, who took over 100 photos of her. The body here is less about nudity and more about a Renaissance ideal of perfect beauty, and Lisa Lyon is an ideal of the masculine and feminine combined. Mapplethorpe would sometimes cover her body with graphite to increase its luminosity.

If I had been born one or two hundred years ago, I might have been a sculptor, but photography is a very quick way to see, to make sculpture.

Robert Mapplethorpe: the Perfect Moment exhibition catalogue, Janet Kardon, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Joselit, Kay Larson, University of Pennsylvania. Institute of Contemporary Art, 1989.

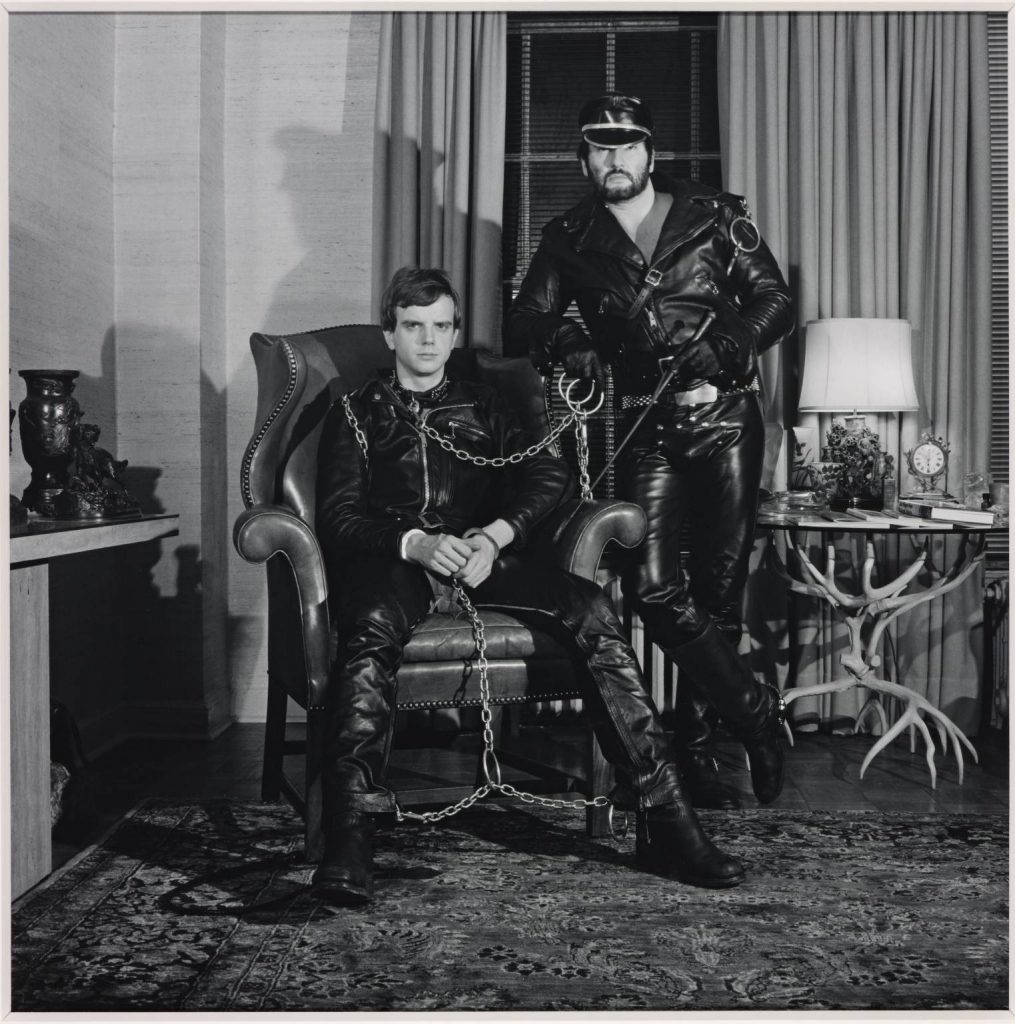

Robert Mapplethorpe, Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter, 1979, Tate and National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Mapplethorpe was an active member of the New York gay scene and in particular, the S&M scene. In the summer of 1989, the traveling exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment brought national attention and notoriety. The issue of public funding for the arts, as well as questions of censorship and obscenity, were hot topics. The Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, USA became worried about an exhibition that contained homoerotic and sadomasochistic images. Conservative and religious organizations, such as the American Family Association, seized on this exhibition to vocally oppose government support for what they called “obscene material”.

I went into photography because it seemed like the perfect vehicle for commenting on the madness of today’s existence.

Mapplethorpe exhibition, Germano Celant, Hayward Gallery, 1996.

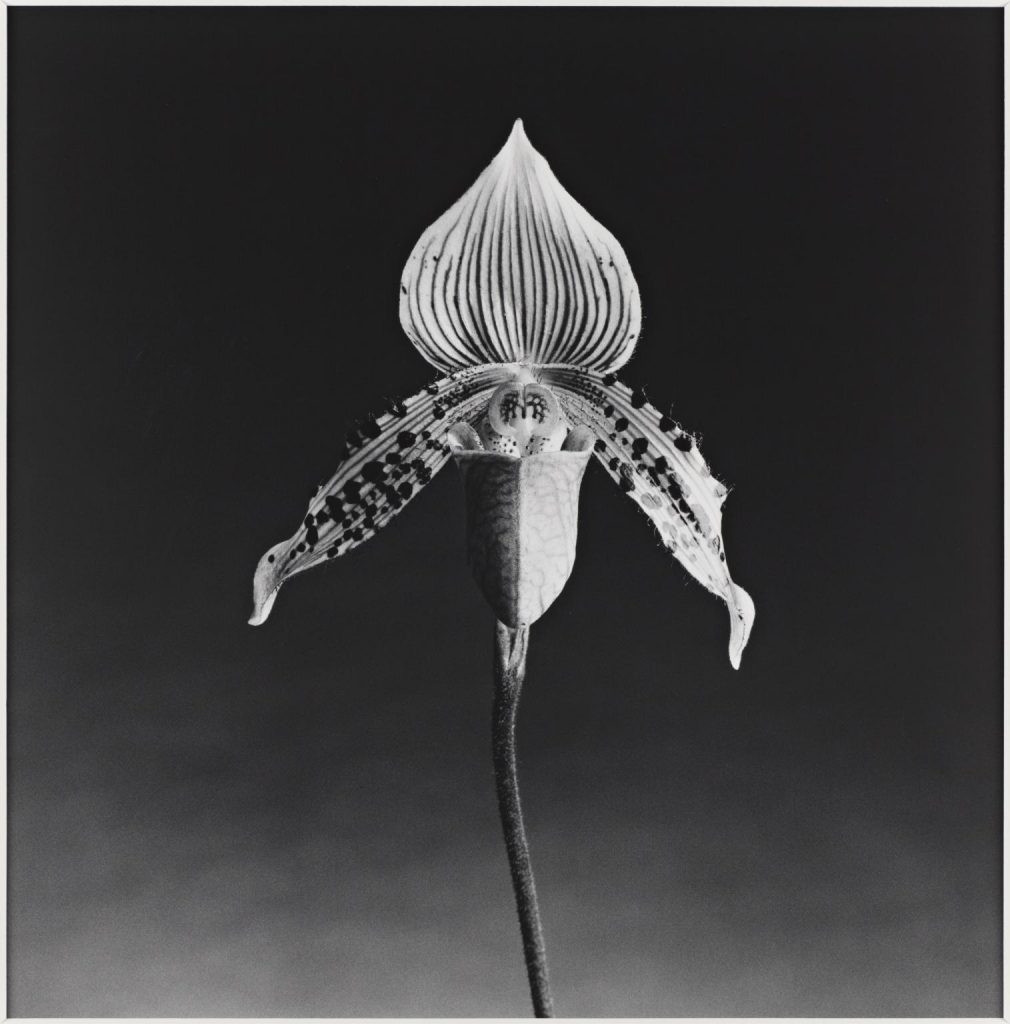

Robert Mapplethorpe, Orchid, 1987, Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

The 1980s saw the often fatal HIV virus tear through communities across the world. Mapplethorpe himself said, “This AIDS stuff is scary, I hope I don’t get it.” Could it be said that Mapplethorpe was part of a long line of artists who morph into their work so much so that it kills them, such as Caravaggio and Van Gogh? Mapplethorpe died in 1989 of an HIV/AIDS-related illness. He was just 42. He left behind the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation which continues to raise funds to promote photography and fund HIV/AIDS research to this day.

Guest Author’s bio:

Ian Munday – since his retirement to Wales, Ian has been studying art history and creative writing. He gives guided garden tours at Powis Castle in Welshpool and also assists at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in Machynlleth.

Here you can read Ian’s article about the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!