Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

Sex, spirituality, love, and loss – for artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz these were the main subjects of the art he created from the 1970s until the early 1990s when he died of AIDS. Always hard-lined, he created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism.

Largely self-taught, Wojnarowicz was mixing everything that shook the New York artistic landscape of those times: graffiti, no-wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and Neo-Expressionist paintings. Radical and extreme in his art and writing, he documented and illuminated a dark period in US history that unfolded around the AIDS crisis and the cultural conflicts of the epoch. Still, even after so many years, his art is like a punch in the face.

Wojnarowicz was always an outsider. His parents divorced and then disappeared when he was two, leaving him to a succession of temporary homes and often abusive relationships. He was a victim of childhood abuse and during his teenage years was a street hustler. As an adult, though, he quickly emerged as one of the most prominent and prolific members of an avant-garde wing that mixed many mediums.

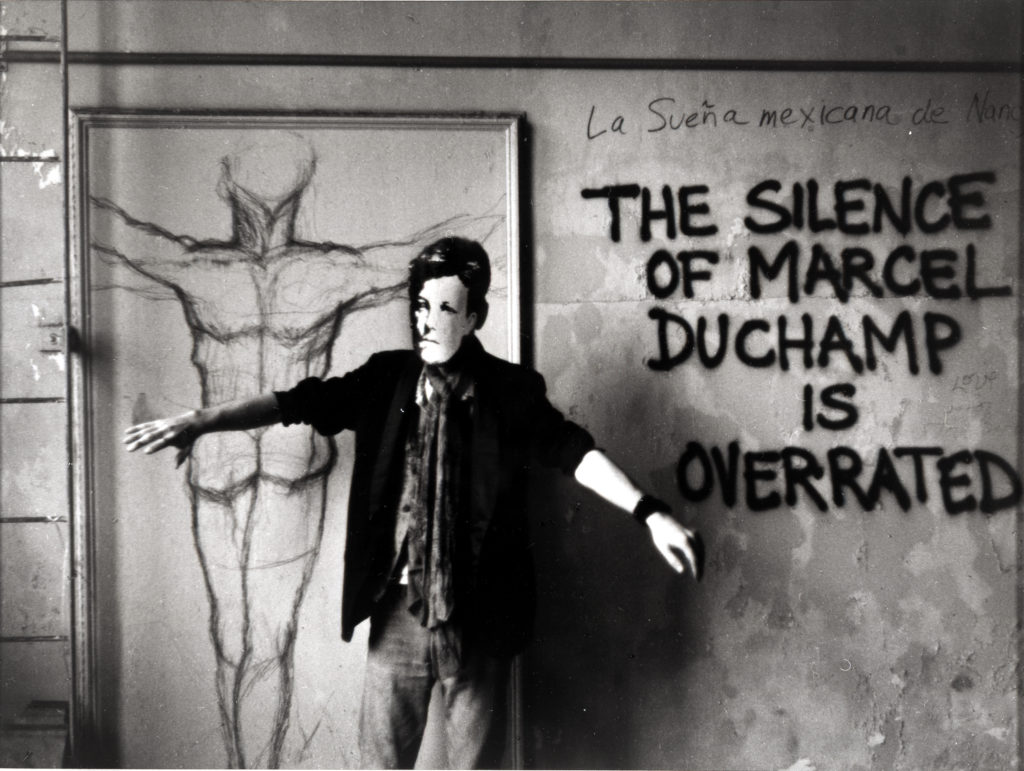

In his beginnings as an artist in the late 1970s, he made a mask of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud out of cardstock and a rubber band, using a famous photograph of the poet at the age of 17. With it, he took a series of photos of his friends wearing it around New York City: Rimbaud in a graffitied subway train; Rimbaud crossing avenue in rush-hour traffic; Rimbaud lying naked on a bed with his penis in one hand. Fifty years later, Wojnarowicz is like a reincarnation of Rimbaud: young, gay, and prematurely dead.

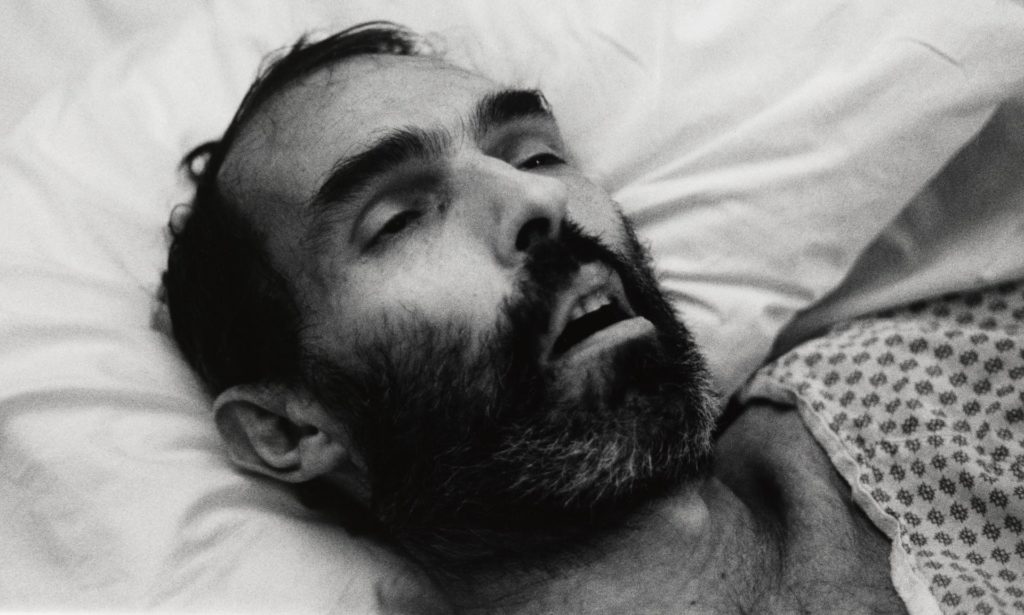

Wojnarowicz became a successful artist, connected to other prolific artists of the time such as Nan Goldin, Peter Hujar, Luis Frangella, and Karen Finley. In 1987 his longtime mentor and lover, the photographer Peter Hujar, died of AIDS. Hujar, 20 years Wojnarowicz’s senior, was the first one to treat Wojnarowicz seriously. When he was dying, they shared the same apartment. Wojnarowicz took a series of harrowing photographs from his deathbed. The artist never recovered from the loss of Hujar, and that year was a turning point in his life. Only months later, he found out he too was HIV-positive.

From that moment Wojnarowicz’s life was filled with defiance and moral outrage. He created works fully charged with political content, notably around the injustices, social and legal, inherent in the response to the AIDS epidemic. When he and the people around him were suffering and dying from the disease and as a consequence of government inaction, he became an impassioned activist. AIDS drugs were expensive; most patients couldn’t get access to them. The misinformation about how HIV was contracted spread widely, and fear of the disease ignited vicious public homophobia. At this time, some Republican lawmakers called for homosexuals to be quarantined and even killed. Wojnarowicz’s art turned to pure fury.

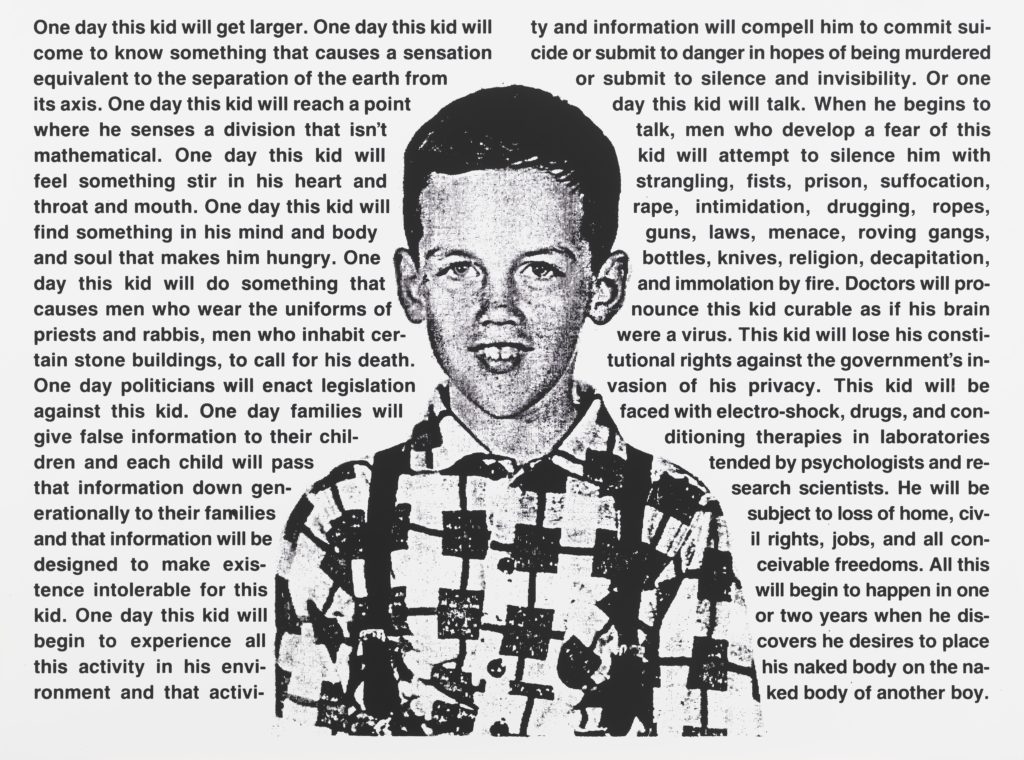

The perfect example of such rage is this photo-text collage entitled Untitled (One Day This Kid). The kid is David Wojnarowicz himself as child, an average boy from the 1950s. But around the photo we can read texts forecasting the artist’s future as a homosexual who is persecuted by his family, church, school, government, and the legal and medical communities. Among other abuses, he will “be faced with electro-shock, drugs, and conditioning therapies” as well as “be subject to loss of home, civil rights, jobs, and all conceivable freedoms” — all because, the text concludes, “he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.”

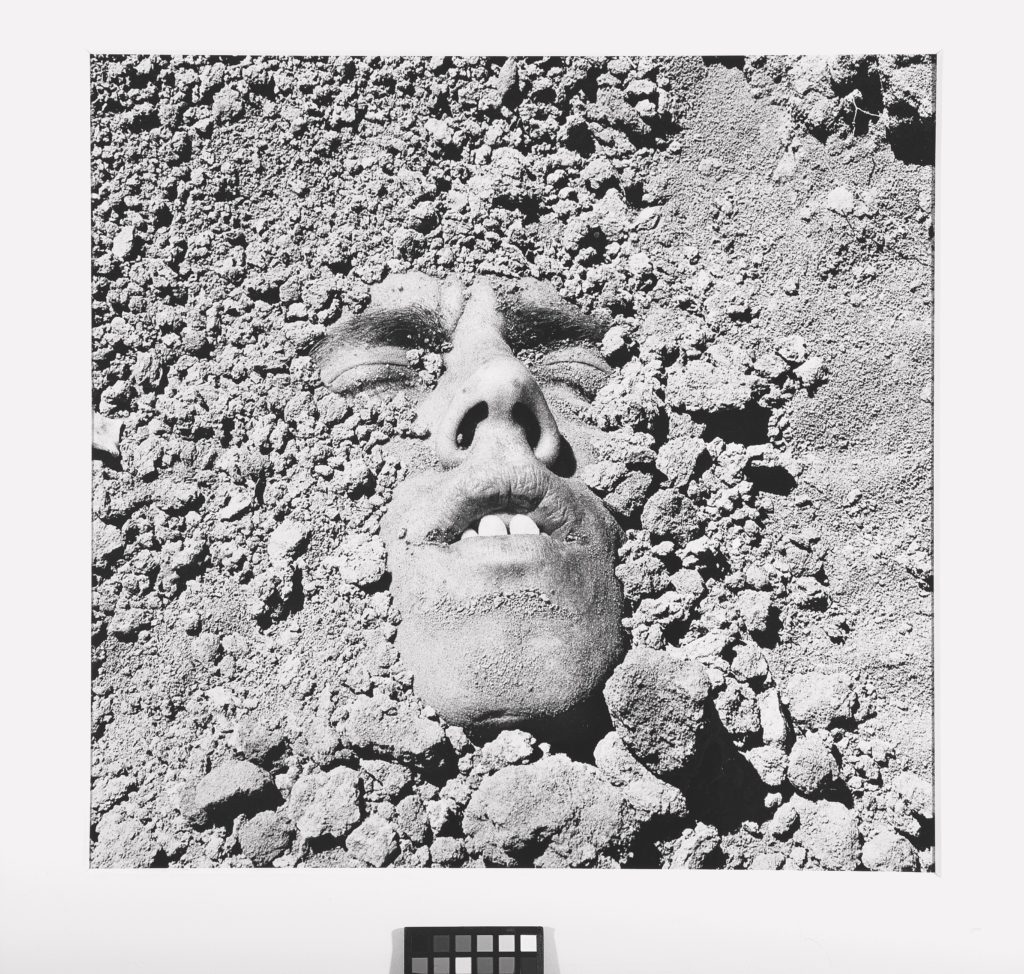

Untitled (Face in Dirt), a photograph taken less than a year before he died, is one of his most famous works. Wojnarowicz lies in a shallow grave, his face just barely emerging from the dry earth. It’s difficult to imagine a more striking and straightforward message from a dying human being.

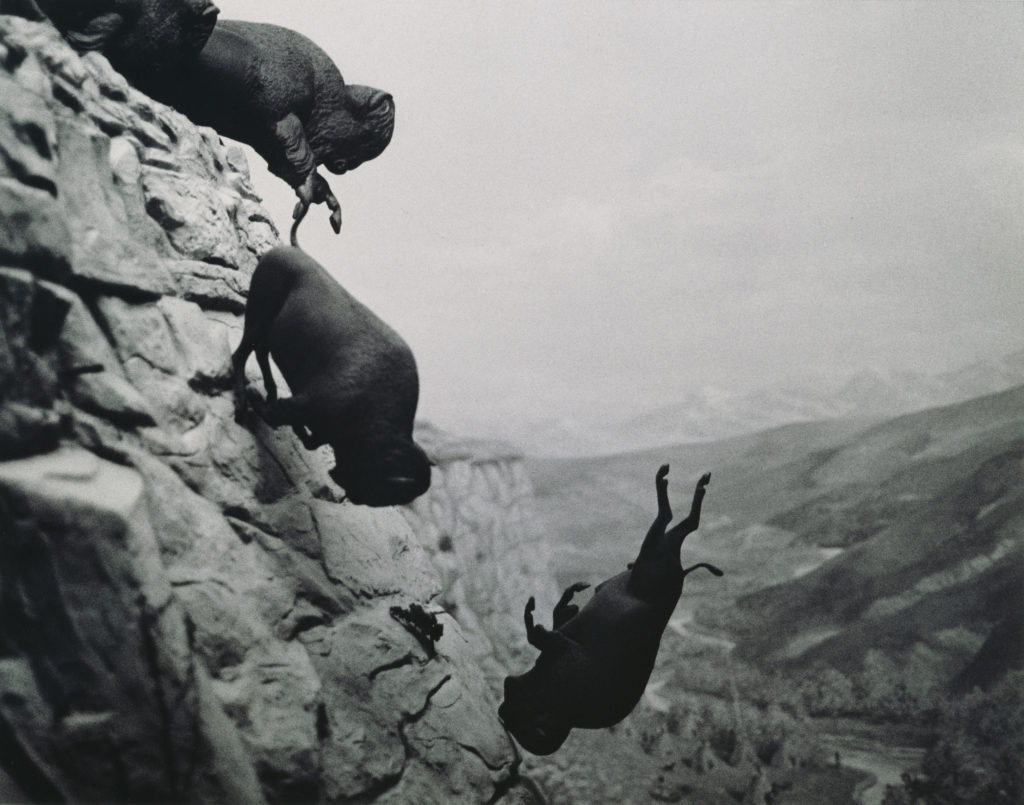

If you think you haven’t seen any of Wojnarowicz’s work before, you may be wrong. In 1989, the band U2 adopted the iconic tumbling buffalo photograph, Untitled (Buffalo), for their single release One. This single, and the album that it came from, achieved multi-platinum status and the band donated much of its earnings to AIDS charities.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!