5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Following World War II, numerous like-minded European artists claimed complete creative independence. Considering they had a common vision, they banded together and formed a collective called CoBrA. It was the first truly international post-World War II avant-garde art movement (and some say the last one of the 20th century). CoBrA is an acronym for the three cities from which the majority of its members hail: Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. This name was not chosen by chance: it emphasized the liberation of CoBrA artists from the artistic core that was Paris, as well as from all “-ism” movements. CoBrA was a genuine declaration of independence.

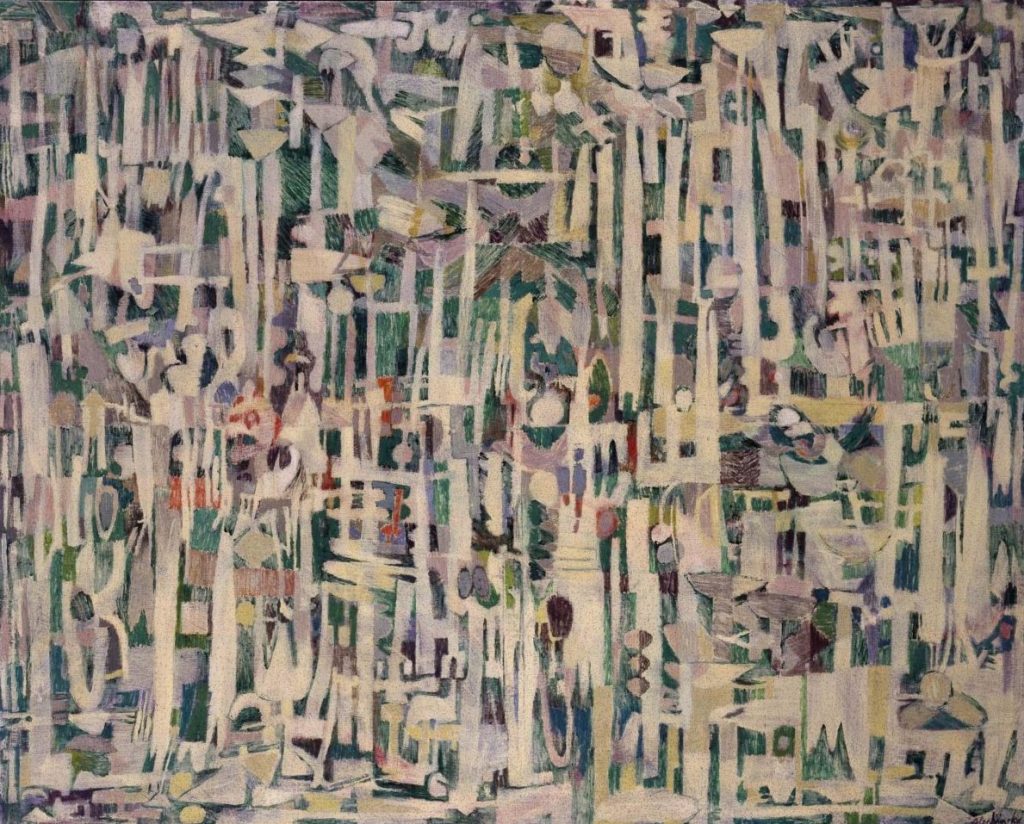

Corneille, Pagan Fable, 1949, CoBrA Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen, Netherlands.

On November 8, 1948 in Paris, some artists were getting bored at a surrealist conference. They were Belgian (Christian Dotremont and Joseph Noiret), Dutch (Karel Appel, Constant, and Corneille), and Danish (Asger Jorn). Tired of sterile intellectual discussions, they left the event and found themselves in a cafe. There, Dotremont wrote a text they adopted as their manifesto. Their ambition: to embody a new creative freedom. These artists were all members of experimental art groups in their home countries and wanted to pursue this approach collaboratively, without borders or specializations (writers can paint and painters can write). This manifesto was also a rallying cry: it was about working together to foster spontaneous art that was free of theories and dogmas. This appeal resonated internationally and united many artists until 1951, when the movement was officially disbanded. However, those three years allowed them to cultivate an attitude that would last beyond the movement itself. It was, in many ways, a starting point.

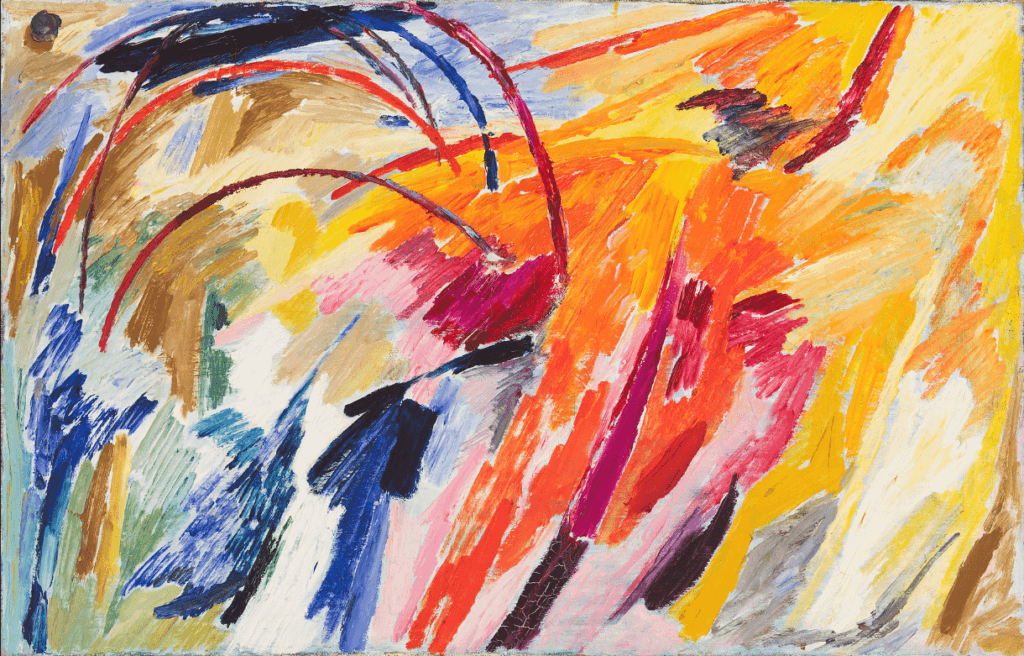

Asger Jorn, L’infinie suffisance, 1965, Beaux-Arts Mons, Mons, Belgium.

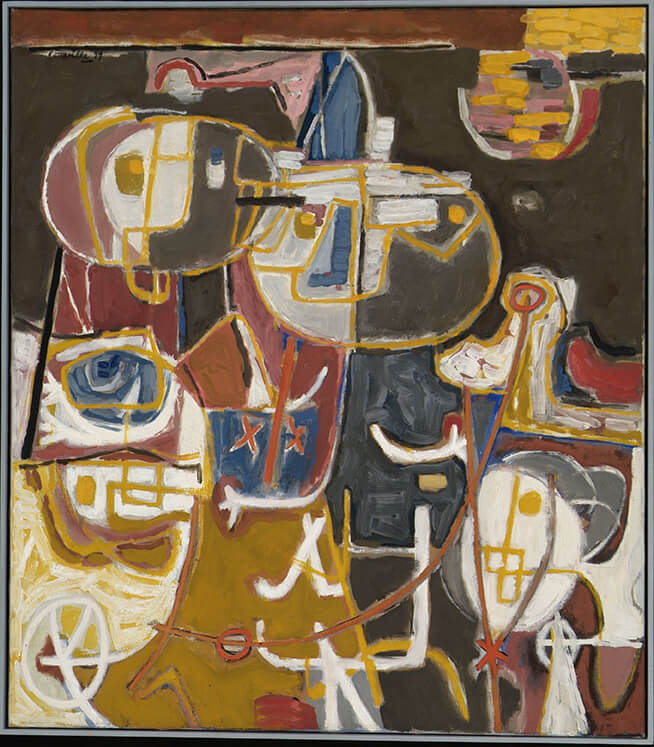

CoBrA’s artists created a free, spontaneous, and intuitive vision of art. They fought against academic tradition, breaking free from old customs and aesthetic theories as well as existing artistic movements. CoBrA’s creative process was based on immediacy and accessibility, and authenticity was highly valued. In direct contrast to Formalism, the artists painted immediately on the canvas without regard for composition. For them, spontaneity liberated the imagination: they believed in matter and the power of imagination that it provided. Matter, with its colors, shapes, and life, was a vital source of inspiration. According to Dotremont, CoBrA urged a return to universal primitivism in opposition to the logic that led to the calamity of world wars.

Else Alfelt, The blasted bridge, CoBrA Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen, Netherlands.

To break free from bourgeois and academic aesthetic rules, CoBrA members looked to popular art, prehistoric art, calligraphy, ancient mythology, children’s and psychiatric disorders, and so on. These were the ultimate manifestation of freedom according to the CoBrA artists. The pleasure of simply painting matter, shapes, and colors, was the essence of CoBrA, for their artistic strategy was based on fun and enjoyment. In this context, they were somewhat in line with Jean Dubuffet’s opinion: the French artist saw the dominant culture as oppressive and suggested the concept of art brut (“raw art”) as an alternative, claiming that artists untrained in the academic art world were the only genuine innovators.

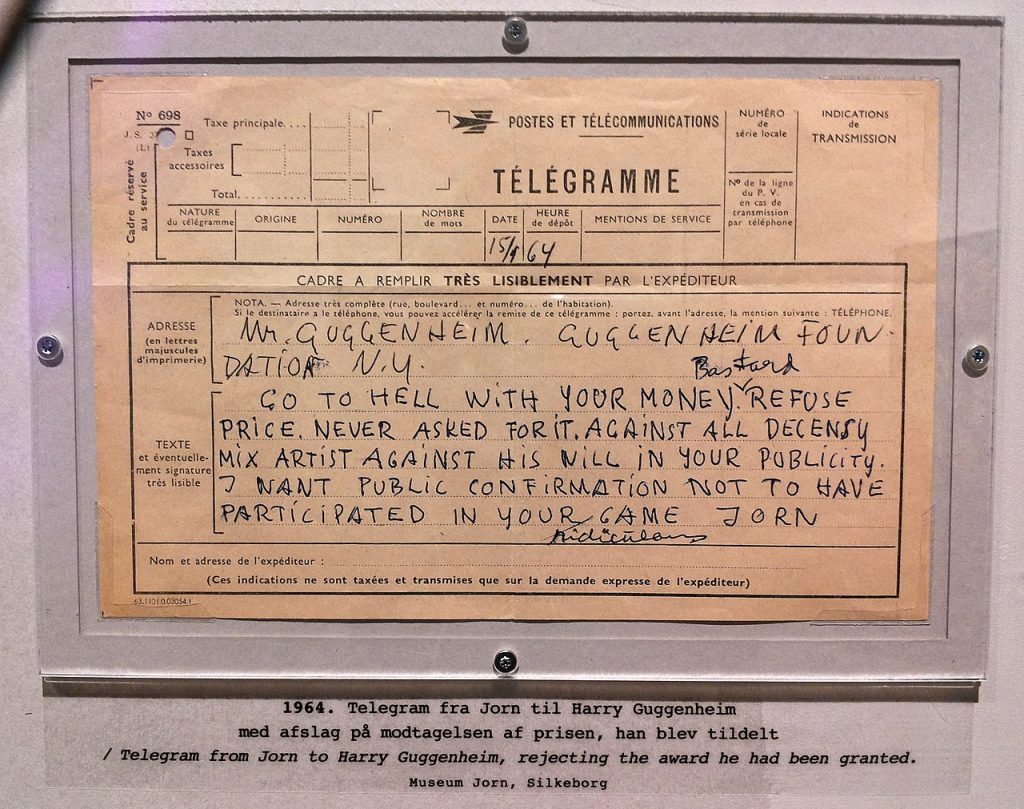

For example, in 1964, faithful to these principles, Asger Jorn refused the Guggenheim Prize. As you can see in the telegram below, he was unambiguous in his rejection.

Asger Jorn’s telegram to Harry Guggenheim, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, Denamark. Photograph by Kasperhj (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Collaboration amongst artists is another important component of CoBrA; their approach emphasized the value of collective creativity. For example, they decorated the interior of a house where they were welcomed during one of their exhibitions, ornamenting the ceilings and walls without a predefined plan. According to them, these were “anti-decorative decorations.” They also organized collective exhibitions and wrote collective essays, as we will see below. There was a desire to create a collaborative environment where artists could inspire and learn from one another.

A painting is not a color and line construction, but rather an animal, a night, a cry, a man, all at the same time.

CoBrA, une explosition artistique et poétique au coeur du XXème siècle, under the direction of Victor Vanoosten, Arteos 2017.

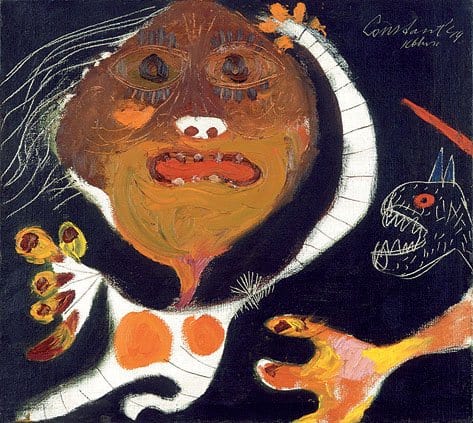

Constant, Untitled (Copenhagen), 1949, Tate Modern, London, UK.

Several styles and strategies were used to demonstrate these principles. In painting, it was frequently distinguished by a forceful brush, an obvious action, and vivid and intense colors. This gave their works a distinct look. Asger Jorn’s works, for example, were occasionally at the crossroads of abstraction and art brut.

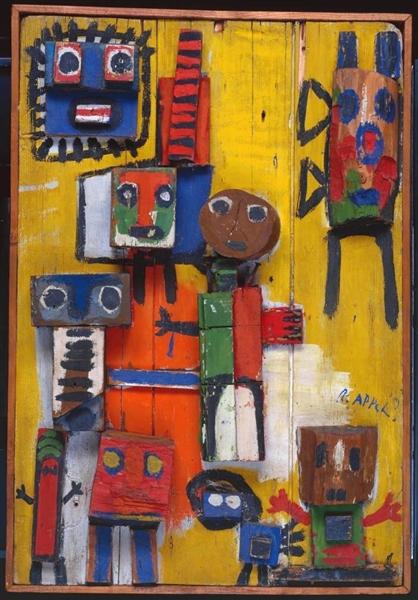

CoBrA’s works were distinguished by a childlike spontaneity and a free sense of expression. For example, Karel Appel made paintings-sculptures that were kind of bricolages. CoBrA artists included symbols, animal figures, and abstract forms in their paintings, sculptures, and engravings. They attempted to penetrate the universal language of art by employing simple images that echo with collective imagination.

Karel Appel, Questionning chilren, 1949, Tate Modern, London, UK.

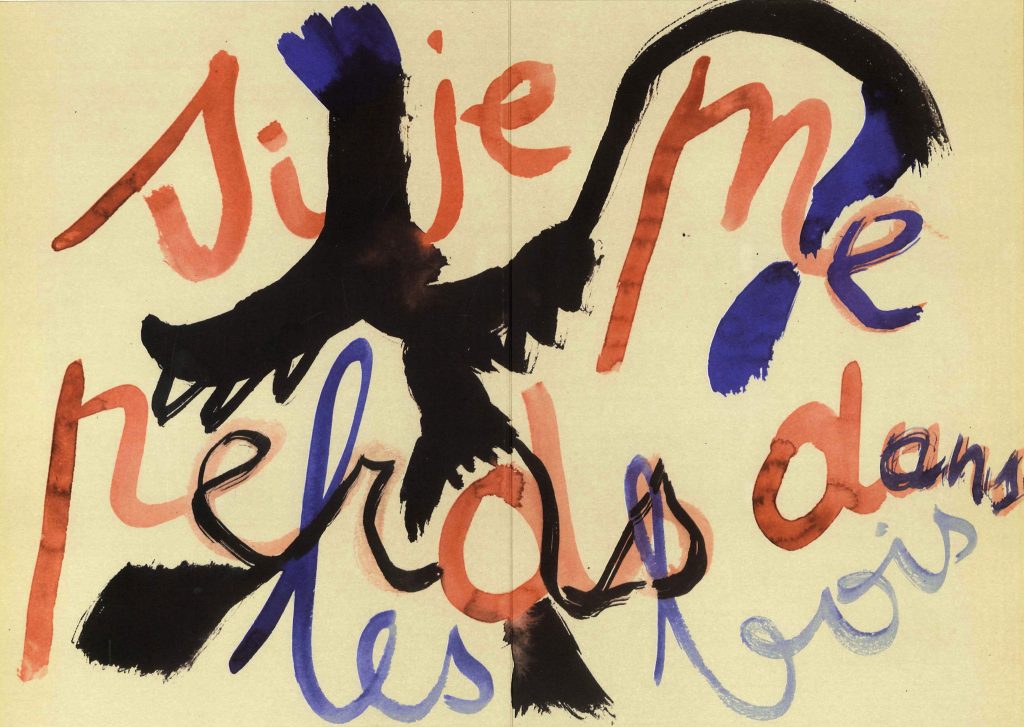

Poetry, and therefore words, were also important components of CoBrA. Many writers have been members of CoBrA, including Simon Vinkenor, Hugo Claus, and, of course, Christian Dotremont. Some painters, such as Corneille, also wrote and published books. Poetry can also be found in their words-paintings, which is what they named work that was sentences embedded in paintings. Dotremont in particular developed them throughout his career, collaborating with numerous artists (Atlan, Pierre Alechinsky, etc.) to produce this work. A few years later, this reflection on writing and its visual element led him to his main creation: the logograms.

Christian Dotremont & Atlan, If I’m Lost in the Woods (part of Les Transformes), 1972, Wikiart.

CoBrA was very active during its three years of existence. The movement was mainly promoted through self-organized exhibitions, and each one provided an opportunity for members to display their work. These events also attracted new members; it was during one such event that Belgian painter and sculptor Pierre Alechinsky decided to join the movement, having been swayed by this singular artistic approach.

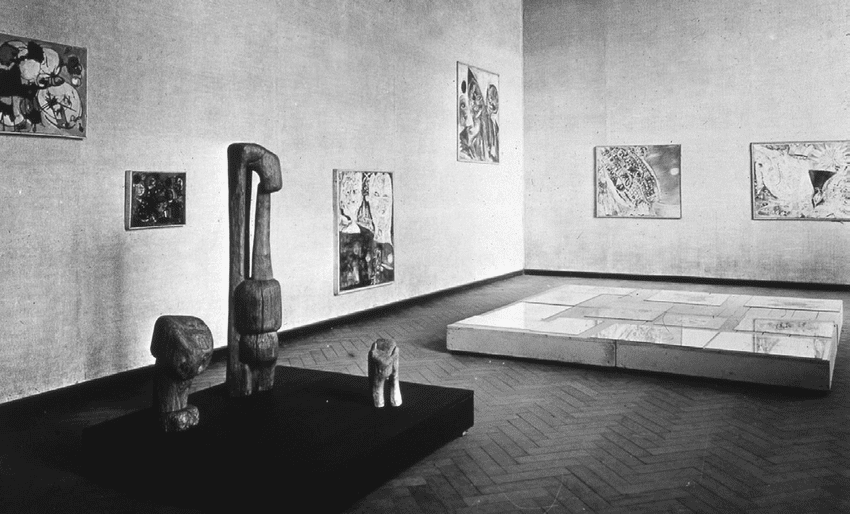

Out of these shows, two deserve to be highlighted. The first was known as the 1st International Exhibition of Experimental Art. It was held at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, supported by its director William Sandberg. You can imagine the legitimacy this brought to the movement given the prestige of this institution. What drew attention, aside from the works on display, was the exhibition design, created by Dutch architect Aldo Van Eyck. He utilized the entire surface of the walls and floors by placing the canvases across the entire height of the walls, unlike the standard method of hanging paintings at eye level. He also created sculpture podiums in black and white. His intention was to stimulate the audience and convey vitality in the space itself. At the time, such design was absolutely innovative. According to Dotremont, it was the “first spontaneous meeting of popular art and free experimental art.”

View of CoBrA exhibition at Stedelijk Museum, 1949, Researchgate.

In 1951, the 2nd International Exhibition of Experimental Art took place in Liège’s Palace of Fine Arts. Dotremont and Jorn were both in the sanatorium at the time (they had tuberculosis), so they entrusted the organizing to Pierre Alechinsky, with Aldo Van Eyck again working on the exhibition design. The exhibition featured a tribute to CoBrA’s predecessors, including the works of Joan Mirò, Alberto Giacometti, and Wilfredo Lam. The event also included a small experimental and abstract cinema festival.

It was CoBrA’s last major official exhibition.

Pierre Alechinsky, The High Grass, 1951, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

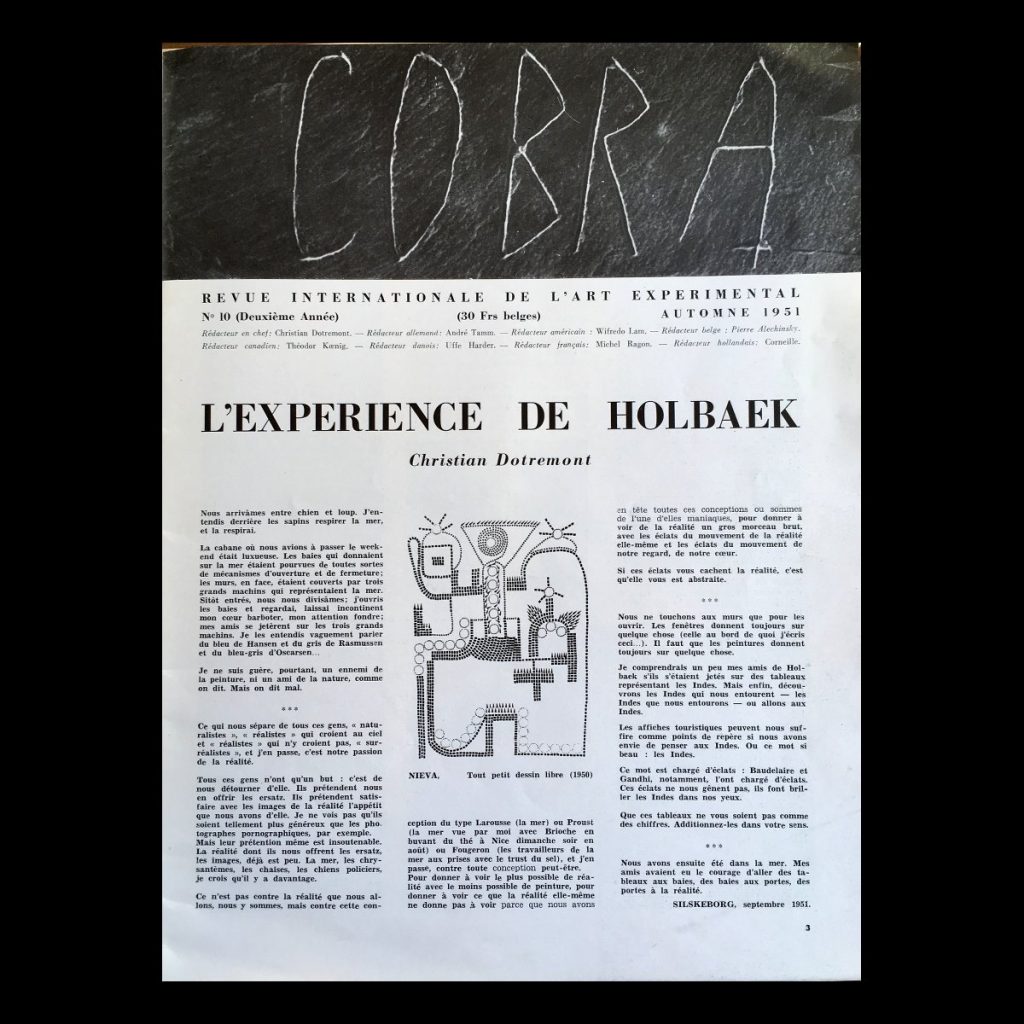

Reviews were frequently created in conjunction with these shows. They were promotional tools distributed globally as a source of current and future information on the group. Manifestos, exhibition catalogs, critical or literary pieces, poetry, and reproductions of CoBrA artists’ works were included in each issue.

The last CoBrA’s review, Librairie Thalie.

Despite its brief existence, the movement had a significant impact on the art world, maintaining its popularity in the years following its demise. As a consequence, CoBrA’s works continue to be exhibited. One of such shows took place in 1959 at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (co-organized by Willam Sandberg of the Stedelijk Museum) where CoBrA pieces were displayed alongside abstract expressionism (represented by, among others, Jackson Pollock and De Koening) as well as Jean Dubuffet. The majority of former CoBrA members remained involved in the artistic and intellectual scene- particularly Asger Jorn and Constant, who were active in the Situationist International, the well-known revolutionary movement of the 1960s. You can find more works by CoBrA artists on the Cobra Museum of Modern Art website.

CoBRA’s legacy continues to inspire artists decades later. Its guiding principles of freedom, spontaneity, and sincerity are constantly in sync with the aspirations of a contemporary artist. Jean-Michel Basquiat is undoubtedly the most renowned example.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump, 1981, private collection, on display at Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!