Blood in (and as) Art

One of the first known expressions of human creativity, the Lascaux cave paintings, were created with blood, a material that has remained significant...

Kaena Daeppen 10 June 2024

A few years ago, two Chinese women drove their Mercedes SUV into the Forbidden City in Beijing. That event created quite a controversy. The least you could say is that it was daring and very disrespectful toward the art site. Sadly, this wasn’t the first time when art has been abused or damaged. Let’s take a look at some other outrageous examples.

“Let’s have some fun and do something crazy” is what these two ladies must have been thinking. On January 13, 2020, the Forbidden City was closed for maintenance and renovation work. A perfect day for their little trip. They photographed themselves with the SUV on the empty main square of the Forbidden City. After having posted the event on social media, many people questioned what they did and how they came that far.

The Forbidden City is a huge complex of significant cultural and historical importance. It was home to the emperors of China between 1420 and 1912 and is a World Heritage Site. That is why it is heavily guarded. So, how could they drive up to the main square? Moreover, cars have been banned from that particular area. Was it their charm, the luxury car, or did they pay off the guards? Following the incident, the Palace Museum issued an official apology explaining the tourists were attending a private event at the museum. The statement was, however, received skeptically by the public.

Luckily, it seems the incident didn’t cause any actual damage to the historical site, which, unfortunately, cannot be said about the following examples. Artists give their heart and soul to the creation of their works. They are often filled with emotion and meaning. Above all, the most precious pieces have outstanding technique. This is why they are admired by so many people. That is, up to the day that some unfortunate person damages the artwork due to carelessness, anger, insanity, or, like in the first case, poor intentions.

In 1917, the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp created his ready-made Fountain, a porcelain urinal. However, from the first day, art critics started to debate whether this was actually art. The world was about to see the first artwork that wasn’t really created by the artist. That is to say, Duchamp simply bought a urinal, placed it upside down, and signed it with the pseudonym R. Mutt. The original was lost over time, however Duchamp agreed to have eight replicas made. These are now displayed in the world’s biggest museums.

Meanwhile, at one of those museums, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the piece was vandalized by Pierre Pinoncelli. He hit it with a small hammer leaving it slightly chipped. That happened in 2006. At that time, Pinoncelli was a 76-year-old performance artist. In a later interview, he claimed that his attack was a work of performance art that might have pleased Dadaist artists. Duchamp’s intention was to make a piece that criticized traditional values in the art world and in particular museum art. More than making a joke, the artist proposed the idea that any object, however ordinary it might be, can become a work of art. Subsequently, that’s something that we’re used to nowadays, and even accept. But in 1917 it was an outrage.

So why did Pinoncelli damage the artwork? Pinoncelli, also being an artist himself, didn’t agree with Duchamp when he allowed the replicas to be made in 1964. According to Pinoncelli, his hero betrayed his own principles. Duchamp’s original anarchic idea was turned into another institutional work. As a reaction, Pinoncelli smashed the urinal to rescue it.

Consequently, he was fined €200,000 in moral damages and an additional €14,352 in repair costs. That made his performance an expensive one, but it didn’t seem to bother him too much. He wanted his statement to be clear and known, something in which he succeeded.

This performance wasn’t the first time he targeted the urinal. Thirteen years earlier, when Fountain was on display in Nîmes, France, Pinoncelli peed into it. He was fined for that action too. Meanwhile, the performer wasn’t unknown to the French police. In 1975, the economy was bad in France and people suffered from inflation. That year, he robbed a bank in Nice with a sawed-off shotgun and escaped with ten francs. His first intention was to get away with one franc, but he took ten francs in order to be ahead of inflation. Quite funny, don’t you think?

As a performance artist, Pinoncelli had several confrontations while reacting to matters he didn’t agree with. However, he was still a great art admirer. He said that he would never attack a Rembrandt or a Van Gogh. That would be vandalism to him. This leads us to Rembrandt’s famous painting, The Night Watch.

The Night Watch, a masterpiece by Rembrandt van Rijn, has a long history of vandalism. The first recorded incident took place in 1911. An unemployed navy cook unsuccessfully attempted to cut it with a knife. In 1975, a schoolteacher slashed zigzag lines into it. The painting needed restoration, but traces of the damage are still visible. The man was later determined to have a mental disorder. Still, the museum was shocked and decided to put the painting under permanent guard in 1979.

In 1990, another unemployed man pushed his way through the crowd before the painting and sprayed it with acid chemicals. The guards acted quickly and saved The Night Watch from destruction. The man was very confused, so his reasoning also remains unknown.

In 2019, the Rijksmuseum launched a complete restoration of the masterpiece. Experts operate in a glass chamber, in front of the public. They use very high-tech methods (scanning, high-resolution photography, and computer analysis) to restore not only the painted surface but each layer, from varnish to canvas.

Imagine you are a performance artist and visit a museum. You happen to pass by a bed that is already messy. What

would you do? Would you jump on it and have some minutes of fun before the guards remove you from the bed? That is what happened to Tracey Emin’s My Bed. The work consists of an unmade bed with objects such as a pair of slippers, empty bottles of alcohol, underwear, and even condoms and other trash.

She was inspired to create this work by a phase of depression in her life. At one point, she remained in bed for four days without eating or drinking anything but alcohol. When she looked at the mess that had accumulated in her room, she suddenly realized what she had created.

Then, when the work was on display at the Tate Modern in London, two performance artists, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi, started jumping onto the bed. It seemed like a lot of fun; they even held a pillow fight! The crowd applauded and after around 15 minutes, they were removed from the bed by two security guards. As a result, they called their performance Two Naked Men Jump into Tracey’s Bed.

The two men liked Emin’s idea but wanted to improve the work, which they thought had not gone far enough. Being displayed in a museum, they found the piece too institutionalized. By jumping on it, they sought to restore it to its original state. Sounds like what Pinoncelli did with Duchamp’s Fountain, but less dramatic.

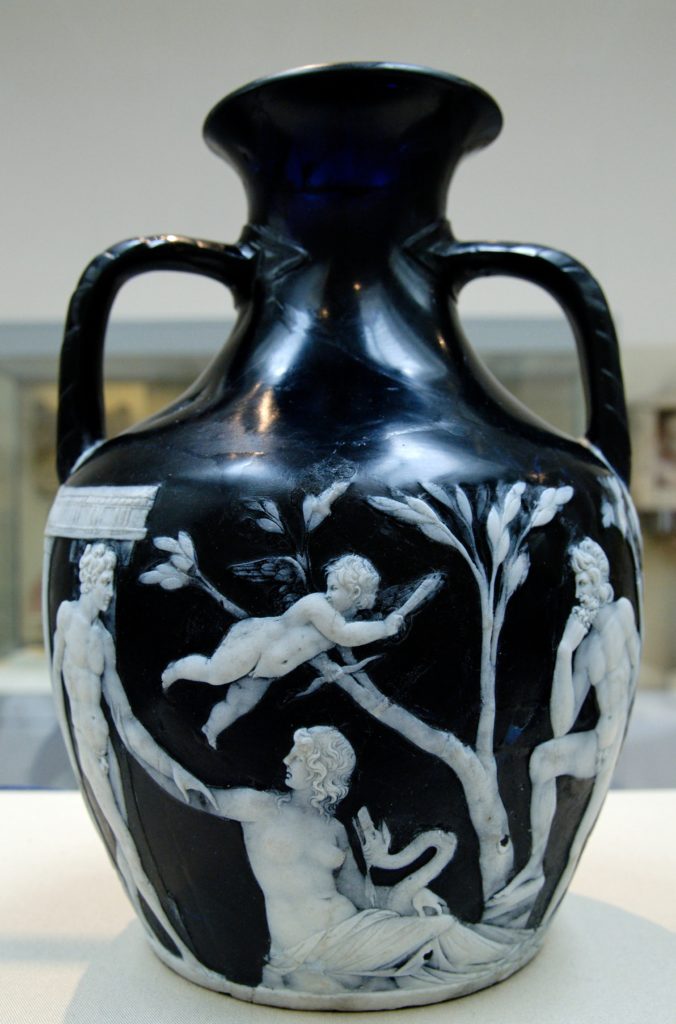

The fragile Portland Vase has survived almost 2000 years without being broken—quite an achievement. The exquisite vase, made of violet-blue glass, featuring depictions of humans and gods, was discovered near Rome in the 16th century and has been in the British Museum since 1810.

However, in 1845, a drunk college student named William Mulcahy, threw another sculpture onto the Portland Vase, smashing both. The vase was splintered into lots of pieces. After the accident, 37 small fragments were still lost so the vase could not be properly restored. It was only a century later, in 1948, that the missing pieces were accidentally found in a box. The vase was restored but was still too fragile to travel to other exhibitions. So, the British Museum put the piece through a final restoration from 1988 to 1989. Nowadays, little damage is visible. Let’s hope that the vase should not require any other conservation work for at least another century.

Sometimes people can be very careless. For instance, in 2010, a woman attending an art class at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York lost her balance and tripped into the painting The Actor by Pablo Picasso. She damaged the artwork and left a six inch (15 cm) tear in the lower right-hand corner of the canvas. Luckily, the rip evidently didn’t ruin the artwork. The Met repaired the tear immediately, and soon after the event, the painting was available for a large Picasso exhibition.

The painting is an important piece in Picasso’s oeuvre. It marked his move from his Blue Period to his Rose Period. The Actor shows a costumed acrobat and can be seen as the prologue to the series of works that culminate in the enormous canvas Family of Saltimbanques.

When you see the number of incidents that have happened with The Little Mermaid by Edvard Eriksen, you might think that it has become a kind of local sport. Although the statue is very well known and is placed in a visible waterside setting, it has been defaced multiple times. In fact, it is difficult to call today’s statue original because it has essentially been rebuilt.

Since 1964, its head has been sawed off, stolen, replaced, and stolen again. Its arm has been sawed off and stolen, it has been blasted off its rock base by dynamite, and it has been covered with just about every color of paint imaginable. Poor mermaid!

As Denmark is the birthplace of Lego, wouldn’t it be a fun idea to rebuild the statue in Lego? So, whenever a piece of the mermaid is broken or stolen, authorities could simply put in a replacement brick…

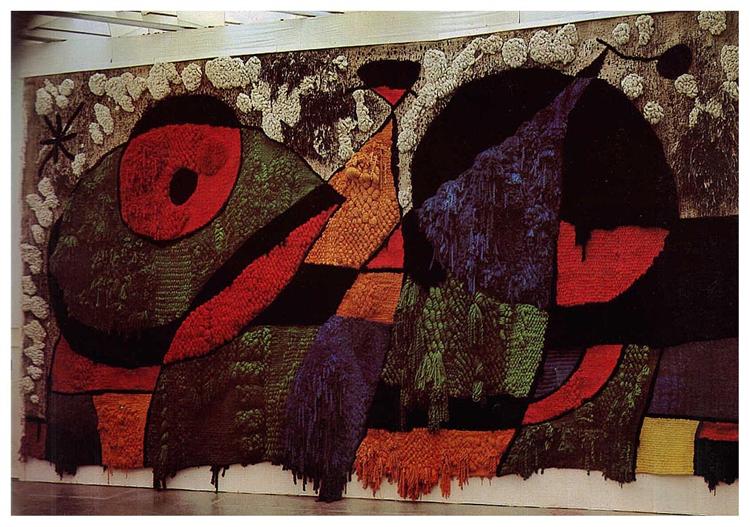

It is not always one single person that can damage an artwork. With the collapse of the World Trade Center in New York City on September 11th, 2001, many artworks were lost. The buildings housed many public works and the private collections of companies. For example, The World Trade Center Tapestry by Joan Miró and Josep Royo was destroyed after the plane crashed into the South Tower (the work was exhibited in the lobby).

At first, when Miró was asked to make a large tapestry for the World Trade Center, he declined, arguing that he had no experience making tapestries. However, after his daughter recovered from an accident in Spain, the artist agreed to make a tapestry for the hospital that had treated her, as a token of his gratitude. Josep Royo, with whom he created several other tapestries, guided him in the technique of tapestry weaving.

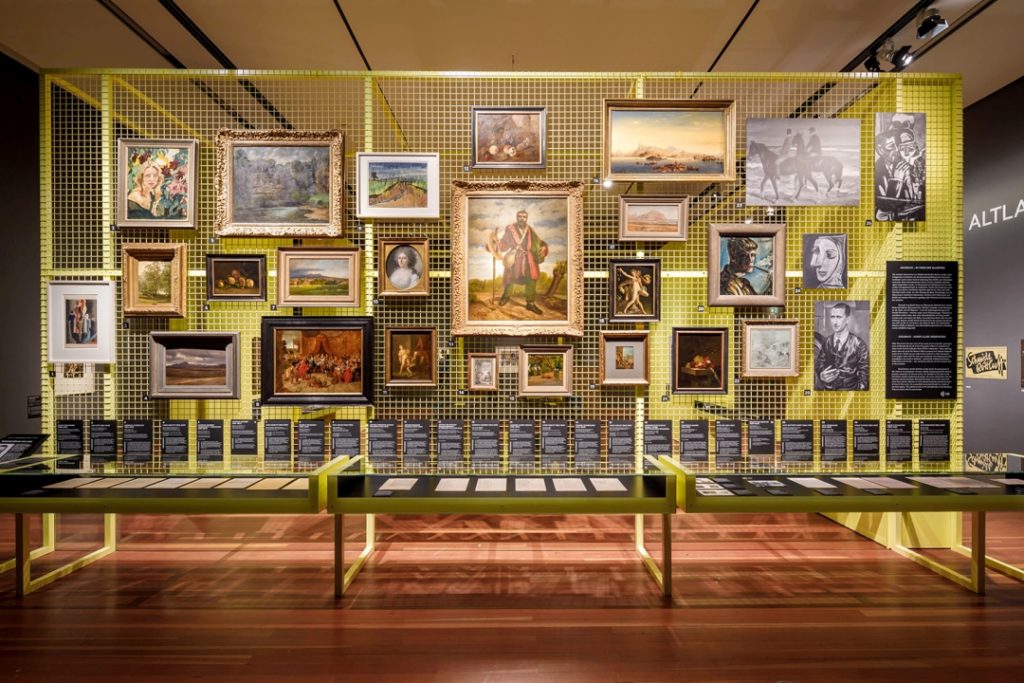

To finish this list of damaged art, let’s dive into a story about the Nazis during World War II. It is known that the Nazis seized many valuable artworks from wealthy Jewish people.

In 2011, German officials made an amazing discovery. Due to suspicious behavior, they were monitoring a man named Cornelius Gurlitt. Their attention was caught when they found out that this man was not registered with tax authorities or social services and had neither a pension nor health insurance. Officially, he didn’t exist.

When they searched Gurlitt’s apartment in a Munich suburb, they couldn’t believe their eyes. Hidden behind mountains of rotting food, they discovered over 1500 paintings. Among these works, they found paintings by Picasso, Matisse, and Renoir. After some examination, it turned out that these were the works that were thought to have been destroyed during World War II.

How did this man lay his hands on such a treasure? The collection apparently came from his father, Hildebrandt Gurlitt, who was an art historian when the Nazis seized power in the 1930s. He acquired hundreds of paintings sold for virtually nothing by Jews attempting to escape Nazi rule. In the chaos, Gurlitt probably also stole art works. Anyway, it turned out that he did a good deed. Without Gurlitt, these pieces would have been destroyed. Gurlitt, the son, lived an unnoticed life and made a living by selling low-profile pieces from this extensive collection. After a complete audit of the works officials began their search for the original owners.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!