The Seams of Royalty: Justine Picardie’s Fashioning the Crown

Fashioning the Crown: A Story of Power, Conflict, and Couture is Justine Picardie’s latest book. She explores all the ways haute couture and...

Errika Gerakiti 23 February 2026

Here we present to you nine ladies wearing red dresses painted by famous artists. You will find Madonnas, prostitutes, symbolic figures, and even a journalist. Red symbolizes many things in art history. Read about all its meanings! Choose your favorite model from our selection of ladies wearing red dresses in art.

To start with, red has long been linked to authority, prestige, and affluence. Historically, it was worn by rulers such as kings and princes, as well as by Roman Catholic cardinals. In medieval art, artists used red to highlight figures of great importance; Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary were often depicted in garments of this color. Additionally, red came to represent martyrdom and self-sacrifice, largely because of its connection to blood.

Another association of red is love and seduction, sexuality, eroticism, and immorality. It was long seen as having a dark side, particularly in Christian theology. Red was associated with sexual passion, anger, sin, and the devil. In the Old Testament of the Bible, the Book of Isaiah says: “Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow. In the New Testament, specifically in the Book of Revelation, the Antichrist is depicted as a red monster, ridden by a woman dressed in scarlet, known as the Whore of Babylon. This might be why red was also associated with prostitution. There are so many associations that contradict each other!

The Lucca Madonna functioned as an object of private devotion for an unidentified patron. During the 14th century, numerous paintings depicted the Virgin Mary dressed in her customary red garment beneath a blue mantle, holding the Christ Child in a variety of poses. The Lucca Madonna belongs to this well-established visual tradition.

The huge drapery in red covers her whole body. Its symbolic meaning is connected with life, energy, and Jesus Christ’s passion. Again, it is a symbolic color of Christ’s martyrdom and redemption. However natural in appearance, this scene is full of other religious symbolic references. The fruit in the Child’s hand, for example, alludes to the Fall of Man, the consequences of which are overcome through the incarnation of God. The throne with its lion decorations symbolizes not only the judgment seat of the proverbially just king Solomon, an ancestor of Christ, but also the Last Judgement.

This half-length portrait, created by one of my favorite painters, Giorgione, depicts a young woman in a fur-trimmed red cloak. The laurel tree may be intended as a coded reference to the subject’s name, but it could also be an attribute of poetry. Yet another possibility is that this young lady was a prostitute. The winter clothing of wealthy Venetian courtesans was usually a beautiful garment lined with fur. Her nonchalant way of wearing the fur supports this interpretation. With this portrait, Giorgione created a prototype for later depictions of courtesans in Venetian painting.

The informal pose and dress—a housecoat, with illuminated deep red elements and tied casually over the low-cut white undergarment—suggest a familiar relationship between Rembrandt and the model. For this reason, the woman was identified as his later companion Hendrickje Stoffels. The pictorial type reveals his familiarity with Palma Vecchio’s portraits of courtesans. This is confirmed by scientific investigations showing that the position of the right arm originally corresponded with the Venetian model but was then increasingly modified. While the ring on Stoffels’ finger shows her status as a married woman, the courtesan’s pose reflects an extramarital relationship, disapproved of by the Church.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir portrayed Gabrielle Renard in over 200 works. In a number of these images, she appears dressed in the same simple, square-necked dress as the one shown here. By 1908, she had been part of Renoir’s household for 14 years, serving not only as a nanny and housekeeper but also as a model and close companion to the aging painter.

This painting’s gold and brownish-red palette, loose brushwork, and stylized, heavy forms typify Renoir’s late work. He adopted the style in response to the ancient murals of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which he had seen in Naples.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was known for his lively relationships with women. He used his female friends and lovers as models to represent his own image in relation to the heroines of his stories. The model for this painting is Alexa Wilding, who frequently appears in Rossetti’s works from the spring of 1865 onwards.

She holds a type of cup from which traditionally close friends and especially lovers would drink. Here, the cup is suitably embellished with heart-shaped designs. The frame of this work is inscribed with “Douce nuit et joyeux jour/ A chevalier de bel amour.” (Sweet night and pleasant day/to the beautifully loved knight.) This inscription shows that the image probably represents a toast to the woman’s knight, who is leaving or has already left for war. While the source of this quote is uncertain, it is thought that Rossetti, steeped in Arthurian legend, wrote the poem himself.

József Rippl-Rónai, a leading figure of Hungarian Post-Impressionism, was associated with the Nabis group during his years in Paris in the final decade of the 19th century. He later designed the furnishings for the dining room of Count Tivadar Andrássy’s palace in Buda. Among the textile works created for this commission, this tapestry is the sole piece to have survived the II World War.

In the center of the tapestry, the woman in the red dress turns slightly away from the viewer. She holds a tiny flower in one hand while the other hand stretches behind her in a gesture typical of Japanese prints. Dark brown outlines surround the figure and vegetation. The tapestry was embroidered by Rippl-Rónai’s French wife, Lazarine Boudrion.

Egon Schiele seems to have had a thing for red and orange (and for drawings showing naked female bodies, but that is another story). The girl in this drawing is neither Edith, Schiele’s wife, nor Wally, his long-time lover who served as a model for some of his most striking paintings. The name of this girl remains unknown to this day.

Within Edvard Munch’s Frieze of Life series, the theme of the Dance of Life plays a fundamental role. The composition centers on a young couple engaged in a dance. They seem to have melted together as the woman’s red dress wraps itself around the man’s leg. The red color continues like a contour line around the man, running into his clothes. They dance face to face, silent and unsmiling, and the woman’s hair blows toward the man.

Two women stand on either side of the couple. From the left, a young woman dressed in white comes towards us, bright and happy. On the right stands a woman dressed in black, rigid and serious.

When Munch painted Dance of Life in 1899, he was influenced by Symbolism and used color to communicate emotions. Red suggests love, passion, and pain, white stands for youth, innocence, and joy, while black conveys feelings of loneliness, sadness, and death.

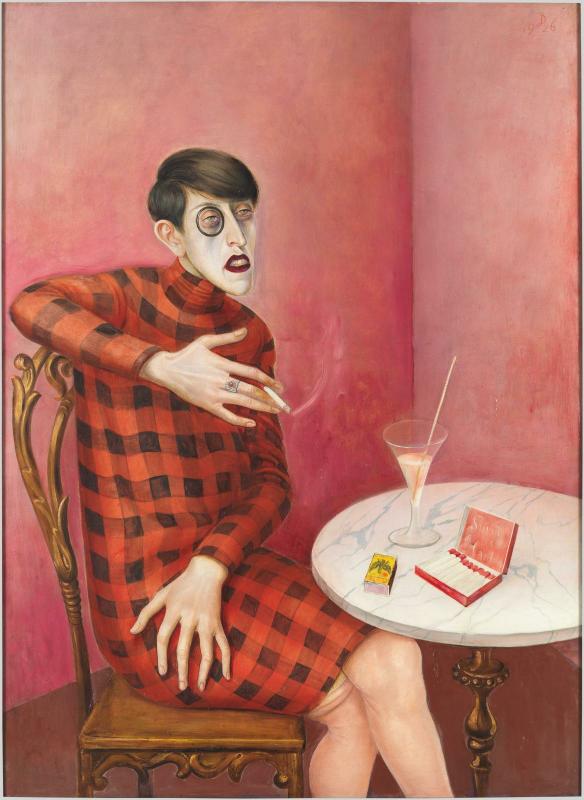

In this work, Otto Dix presents the figure of the “new woman,” whose identity was shaped by the social transformations taking place in Germany during the 1920s. Known in German as the Neue Frau, she rejected traditional expectations and conventions. This modern woman smoked and drank, focused on her career, and showed little concern for marriage or family life. The red-and-black gingham pattern functions as a contemporary symbol of confidence and power.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!