Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

A short haircut, a monocle, sharp facial features with pale skin and dark red lipstick, a plain, figure-disguising dress, and a cigarette casually held in the sitter’s right hand. This androgynous figure set against a pink background is an iconic image of the Weimar Republic and the famous work by German painter Otto Dix. To some, his works might seem awkward or even revolting. They portray a fast-changing German society on the verge of destruction.

The dictionary definition of degenerate states it as “having lost the physical, mental, or moral qualities considered normal and desirable; showing evidence of decline.” In the 1930s, Hitler and the National Socialist Party used the term to denounce modern art as Entartete Kunst to bring the artists’ ideas and concepts under state control. According to the party, what was needed was the idea that all art should represent the German values of Kinder, Küche, Kirche: family, home, and church.

Otto Dix was one such artist deemed by the Nazis to be degenerate and who suffered as a consequence of being branded in this way. Dix, who by the 1930s was well-established as an artist and as a professor at the Kunstakademie in Dresden, was a natural target. He had fought in the Great War, and his paintings, drawings, and etchings reflected the brutality of the war that, on several occasions, had almost taken his life. However, not only did Dix wish to show the public the true face of what had occurred, but he was also keen to show that the futility of the conflict was still going on.

While the new Weimar Republic appeared to be a much better system for the people of Germany, with equality in law and vote for all Germans, it was clearly not. Its laws were weak, with continued shortages, price increases, and hyperinflation. In the 1920s, Dix concentrated on revealing the hypocrisy of a society that was turning its back on what was really happening.

The irony is that the rise of the National Socialist Party was a direct consequence of what the Weimar Republic intended. Yet many of Dix’s paintings were deemed “degenerate,” shown in the infamous 1937 exhibition in Munich and later destroyed. The following are works that Dix produced during the chaotic 1920s, and we can ask ourselves if this is “degenerate” art or if Dix is holding up the mirror to a damaged society.

In Salon I, Otto Dix depicts four aging prostitutes in a brothel. The painting was inspired by a visit to Hamburg in 1921. The weary looks on the three seated together at the table contrast with their naked colleague who caresses herself in front of an unseen client. All are past their prime, dressed in finery and makeup—their attempts to reverse the aging process. Dix seems to be asking what happens to these women as time passes.

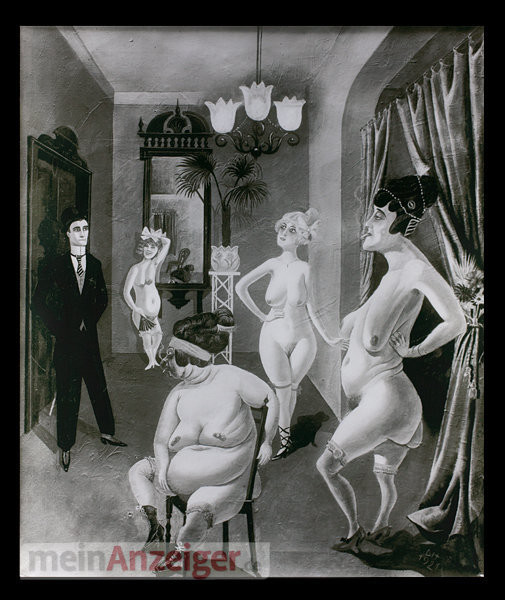

A second painting of this theme, Salon II, later destroyed by the Nazis, was the subject of an obscenity charge. The painting showed girls being examined by the client. In court, Dix said, “The idea of the painting is to depict the whole ghastly, dehumanizing effect of prostitution … The way the women are portrayed is intended to be revolting: to arouse exactly the opposite feeling to lust.”

Anita Berber (1899–1929) was a dancer, writer, and actress from Dresden whose exotic looks won her many admirers in the cabarets of Berlin. Her near-naked performances became legendary, but it was her public appearances that made her name. Her biographer, Leo Lania, said of her, “Whether dancing, in front of the camera or intoxicated, the instrument of her art was her body. She had nothing else. It was her fate to obey it: urgently, passionately.” Berber’s drug addiction and alcoholism were to be her downfall as she died in 1929 from tuberculosis.

After Otto Dix and his wife had seen Berber perform, a friendship developed between the couple and the dancer. In his portrait of her, Dix focuses on the sinuous sexuality that exudes from this woman, from her shiny red bob down through every curve and outline of her body. The red dress quivers and slides, creating the effect of movement.

Despite hardships following the end of World War I, the 1920s were a time when anything could and did happen. In Berlin, art, music, film, and literature reflected this desire to experience everything life could offer. Nowhere was this decadence more apparent than in Berlin’s nightclubs.

While living in Berlin, Otto Dix frequented the cafes and bars. According to Sylvia von Harden’s memoir, Dix met her on the street and stated:

I must paint you! I simply must!… You are representative of an entire epoch!

Otto Dix, Sylvia von Harden, Memories of Otto Dix, 1959

Von Harden was a journalist and poet. She adopted that name to give her writing a more aristocratic slant. The sitter is depicted in the Romanisches Café, a famous center of Weimar Berlin, scornfully nicknamed by many respectable citizens as the “headquarters of the world revolution.” This painting was one of the works deemed “degenerate art” and was exhibited in the infamous 1937 exhibition.

The androgynous portrait typified the way women dressed and behaved at the time. Sylvia’s manly haircut, use of the monocle, and lack of curves created an iconic image replicated in the film Cabaret in 1972 (dir. Bob Fosse).

Our final painting is the triptych Metropolis, finished in 1928. This was not the first time Otto Dix used the compositional style of the triptych to put across his viewpoint. The center panel epitomizes the glamour and decadence of Berlin in the 1920s. Dancing, particularly American jazz and ragtime, was the pastime of choice, symbolizing the freedom felt by the people at the time. The whole scene vibrates with energy—the transvestite dancer in the center shimmers with her “wings” and feathers—the jewel colors of the dresses glow and catch our eye as the band plays syncopated jazz. Life is good!

However, the wings of the triptych tell a different story about Germany at this time: the war-wounded struggling to live, the prostitutes lining the alleyway, and, in the corner, peering around at them is the artist himself. The outcasts turn away from him. The right-hand panel shows the hedonists leaving their cosseted world, passing by the war cripple, ignoring his upturned hat. Dix once said:

All art is exorcism. I paint dreams and visions too; the dreams and visions of my time. Painting is the effort to produce order; order in yourself. There is much chaos in me, much chaos in our time.”

Otto Dix, Artnet

And Otto Dix was right. This degenerate world was heading towards a never-before-seen chaos, not even in Dix’s imagination.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!