The Miniature Rooms of Narcissa Niblack Thorne

The Thorne miniature rooms are the brainchild of Narcissa Thorne, who crafted them between 1932 and 1940 on a 1:12 scale. Incredibly detailed and...

Maya M. Tola 27 May 2024

The ceramic tile art of the Anatolian Seljuks dazzled with its mystical turquoise hues, fantastical creatures, and figural depictions. So, who were the Anatolian Seljuks and what inspired them to create such wildly imaginative ceramic tiles?

The Seljuks originated from the Central Asian Turkic Oğuz tribe. This tribe invaded southwestern Asia during the 11th century, including the territories of Iran, Mesopotamia, Syria, and Turkey. The Anatolian Seljuks derived from the Great Seljuks of Iran. It was the Great Seljuks who created the first çini (handmade glazed ceramic tiles) masterpieces in Iran. They carried this tradition over from their Central Asian roots and later continued this art form in Anatolia.

From 1060 until 1307, the Anatolian Seljuk Empire ruled in Turkey. Their capital city was Konya, located in Central Anatolia. The Anatolian Seljuks decorated their buildings and places of worship with ceramic tiles, thus making Konya an important center of ceramic tile manufacturing. During the 13th century, ceramic tiles were at their peak and also a major component of Anatolian Seljuk architecture. Masters of stonework, the Anatolian Seljuks adorned their magnificent structures with colorful tiles that created an ethereal ambiance.

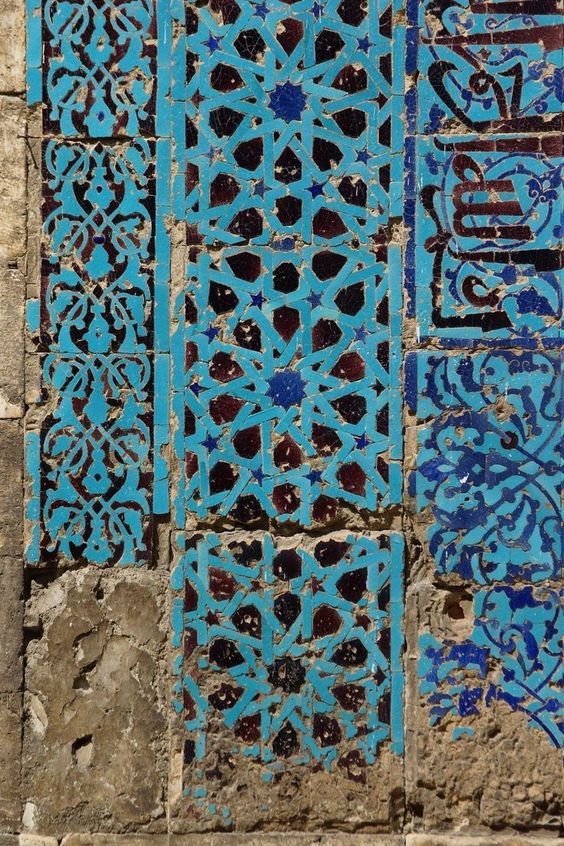

The ceramic tile art of the Anatolian Seljuks is considered the most significant product of their time. Ceramic tiles were used as architectural decoration for interiors and exteriors of both secular and non-secular structures. The most dominant color was turquoise, a vibrant hue that the Anatolian Seljuks associated with the heavens. Other popular colors included deep purple, cobalt blue, and forest green. In rare cases, earth yellows and reddish browns were also applied.

Ceramic tiles adorned many Anatolian Seljuk architectural structures including mosques, tombs, and medrese (koranic schools). Ceramic tile art decorated door archways, minarets, and mihrabs. Mosaic tiles were also used to decorate religious and funerary architecture with geometric compositions or Kufic descriptions. Many examples still exist in dome interiors and mihrab niches. The most common designs and shapes were geometric: stars, diamonds, squares, and crosses.

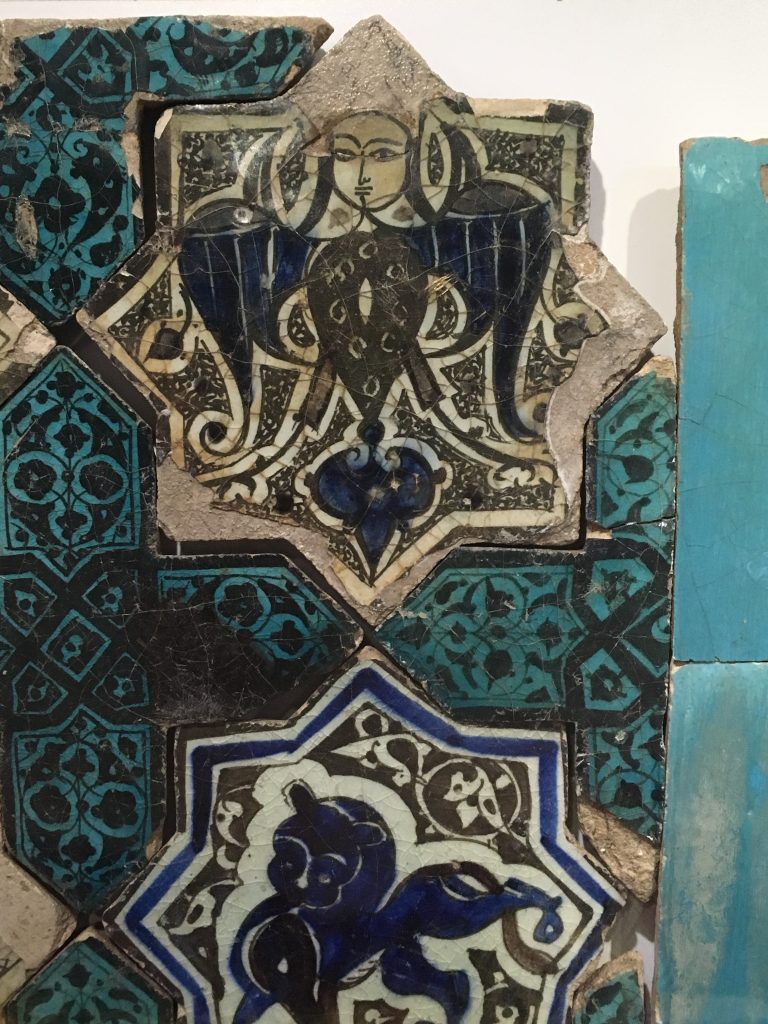

The Anatolian Seljuks ceramic tile art was inspired by both Shamanism and Islamic Sufism. Shamanism was a widespread religion, adopted by the Asian Turks. It infused human and animal forms blessed with natural forces. Many of the tiles feature plant motifs or human and animal figures. Anatolian Seljuks were also influenced by Islamic Sufism, creating their own interpretation of the divine and powerful in their art and architecture.

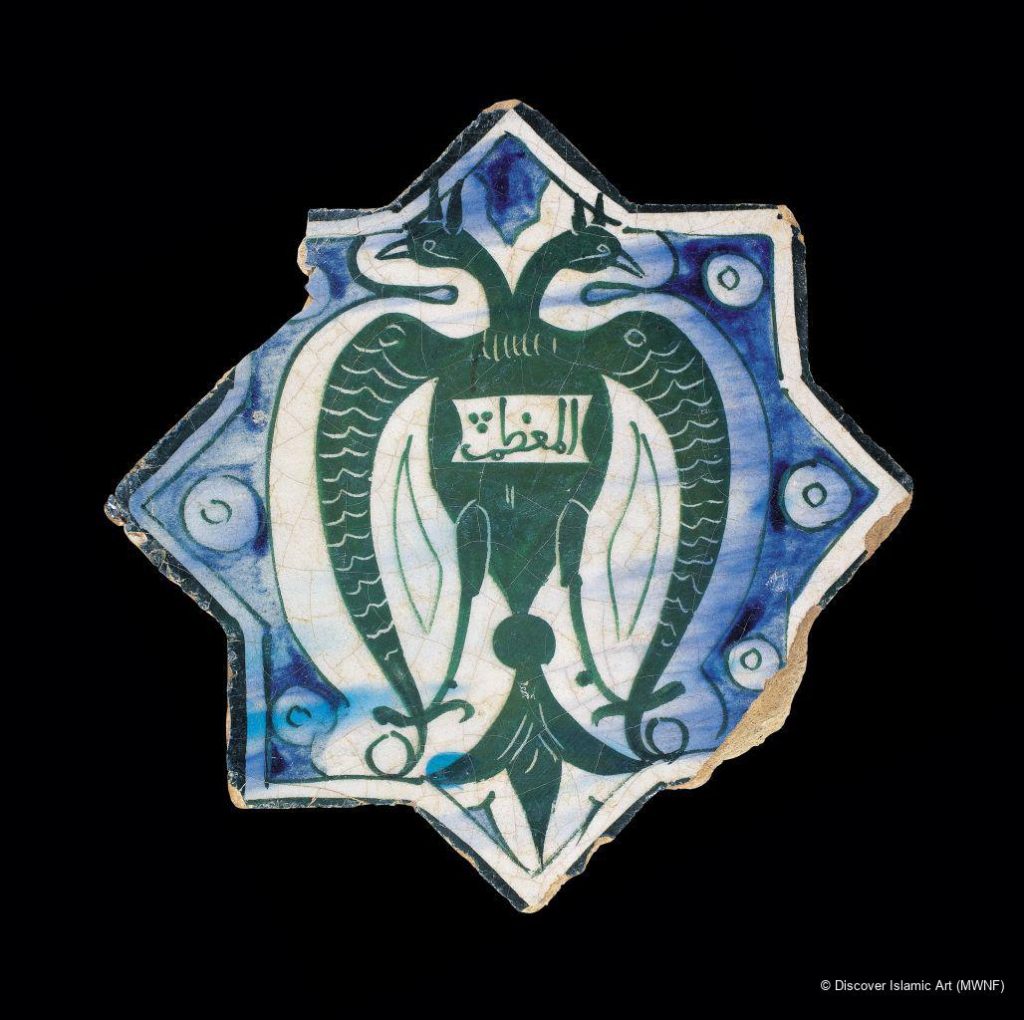

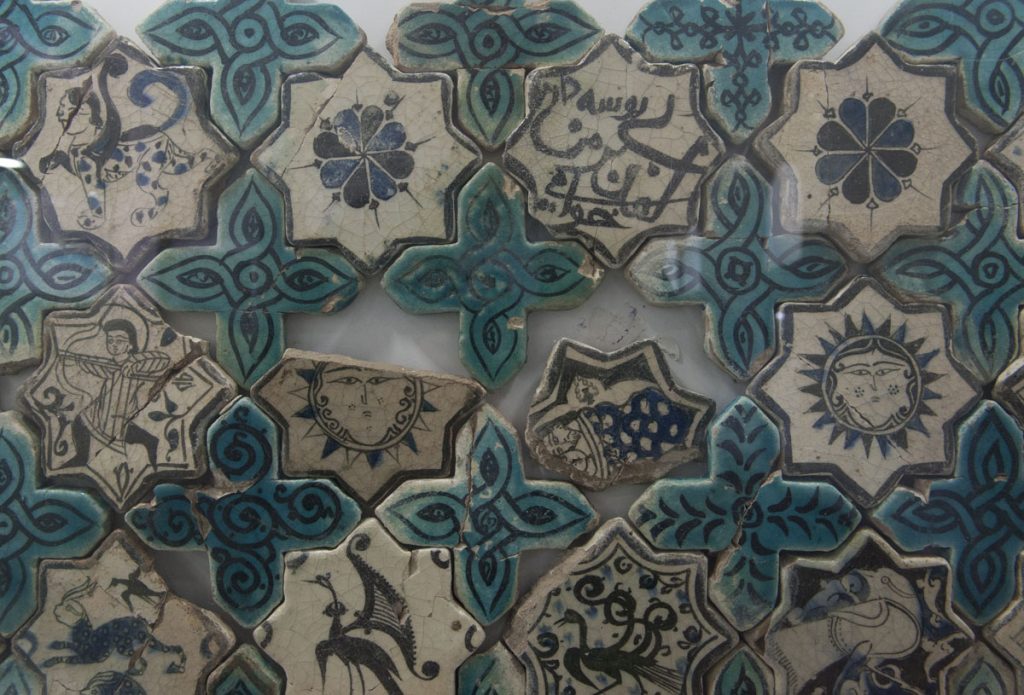

Many of the symbols depicted in ceramic tile art derived from Central Asian Shamanic beliefs. One example is the Tree of Life motif which symbolized a road or a staircase to another world and represented eternal life. This design was often paired with birds and believed to symbolize good luck. Imaginary creatures were also used to express the metaphoric world of the Anatolian Seljuks. For example, an important image symbolic of the Anatolian Seljuks was the double-headed eagle with ears. This animal represented strength, imperial power, and protection – admirable and intimidating qualities of any ruling clan. This symbol often decorated the walls of Anatolian Seljuk structures.

Also popular were symbols of double-headed dragons with knotted bodies, curved mouths, and forked tongues. Other mythical creatures depicted were the sphinx, harpy (half-bird, half-human), siren (half-bird, half-maiden), and dragon-wolf. The double bird motif, typically found in palaces, was believed to possess magical and healing powers. These mythical creatures had wings and tails with spiraled ends. They were thought to protect the sultan and his palace.

Popular animal symbols included lions (protection and strength) and peacocks (paradise or palace life). Meanwhile human figures depicted were of royal status: the sultan, women of the harem, royal entourage, and reputable servants. Typical characteristics include large, almond-shaped eyes, rounded cheeks, long, slender noses, and tiny mouths with moles on their faces. They also had long hair and wore crowns.

The Anatolian Seljuks were rather fond of hunting and displayed hunting scenes in their ceramic tile art. Hunted animals and animals used to hunt shown include bears, foxes, antelopes, wolves, lions, and mountain goats, plus falcons and horses. Their depictions might either be stylized or realistic, but always appear in motion.

The most common technique used by the Anatolian Seljuks was under-glaze transfers. They painted designs directly onto the tile surface. A transparent glaze was then applied over the design, before the tile was fired. This technique is found in all ceramic tile art of the Anatolian Seljuk palaces.

To luster tiles they used the over-glaze technique. A mixture of metallic oxides, such as silver or copper, is applied onto a previously glazed and fired surface. Then the tiles are fired a second time at a low temperature. This produces a range of lustrous brown and yellow tones. Luster tiles were only used to decorate civil and palace architecture. Their examples have been found at the ruins of the Kubad-Abad Palace, located on the shores of Lake Beyşehir (west of Konya), and at Alaeddin Palace in Konya.

The monochrome mosaic tile technique was a decorative staple of Anatolian Seljuk architecture. Tiles were cut into pieces that were then composed into geometric, key-shaped, or star patterns. This technique was typically used to decorate mosques. A prime example is in the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya.

The mina’i, or enamel glazing technique, was carried over from Iranian ceramics of the 12th and 13th centuries. This technique, often used in palace architecture, allowed for more variety of colors and sometimes included gold leaf. Today, the only living example of this technique in Anatolia can be seen at the Alaeddin Köşkü (Villa) in Konya.

The best place to see examples of ceramic tile art from the Anatolian Seljuks is in Konya, Turkey. Other locations across Turkey include Alanya, Malatya, Kayseri, Erzurum, Sivas, and Tokat. The Karatay Medresesi Museum in Konya is a true, cultural treasure that provides an excellent overview of ceramic tile art and techniques as well as stunning examples of stonework from the Anatolian Seljuk period. Opened in 1955 as the Tile Works Museum, this museum also displays ceramic tile art that was discovered during the excavations at Kubad-Abad Palace. Centuries later, the luminous turquoise ceramic tiles continue to impress and their designs leave much to the imagination.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!