Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

“Why have there been no great women artists?” continues to be a question that pops up all too often. The response can be succinctly summarized like this: female artists have existed for centuries, but we just haven’t been aware of them. There are plenty of reasons for our ignorance. The general anonymity surrounding the women whose craft did not call for signatures and women taking their husband’s last name are two among many oversights that have undoubtedly harmed the position women hold in art history, complicating the process of correcting misattribution.

There is, of course, a more sinister explanation for the inveterate lack of women in the arts. It is one that implicates the men surrounding talented women, whether it be husbands, teachers, or art dealers. They often obscured women’s identities and attributed their paintings to male artists. This systematic misattribution essentially meant the erasure of women from the art historical canon, which eventually resulted in their erasure from history itself. Their names have only managed to resurface recently, with the use of technological expertise by scholars who are no longer willing to look the other way. It is worth recognizing the names and exploring the oeuvre of women who have suffered from such injustices. There are many who have been “discovered” so far and many more still waiting.

Sofonisba Anguissola (1535–1625) was an Italian Renaissance painter specializing in portraits. One of the first women to receive formal artistic training, she quickly reached international levels of fame. Her artistic genius was eminent enough for the Spanish court to invite her to tutor the queen, Elizabeth of Valois, and to serve as a court painter for King Phillip II. However, her official position was “lady-in-waiting”. This made identifying her works difficult later on, combined with the fact that she rarely signed them.

Court portraits make up the majority of her oeuvre. The explanation for their misattribution is rather simple: Anguissola was the “unofficial” court portrait painter. This meant there also had to be an official one, a subpar, but male, painter. Alonso Sánchez Coello assumed that role, serving mostly as an assistant to Anguissola and helping her with her workload.

A fire that broke out in the Spanish court during the 17th century destroyed most of her works. When her remaining paintings were found unsigned, a consultation of the historical record hinted towards the author of the works being Coello, as he was the officially appointed court painter during Philip’s reign. As a result, historians attributed almost all of Sofonisba Anguissola’s court portraits to him, a misattribution that lasted for three centuries.

This portrait depicts the king with austerity, virility, and pride, all essential characteristics for a monarch. No one could fathom that a “feminine hand” had executed this portrait. The revelation of the true master behind Philip’s portrait happened in the 1910s. Until then, historians recognized Coello as its painter, both because of the records and the similarity of his style to Anguissola’s. The two collaborated for many years and influenced each other accordingly. She possessed the Northern Italian mastery of color and light. He, an ardent follower of Titian, exhibited elaborate realism in his works. The distinctive elements of the two artists mingled playfully in their royal portraits.

Due to the nature of her talent, historians mislabeled many of Anguissola’s works as Titian’s or Zurbaran’s, among other big names. Such misattributions were easier to dispel, however, due to chronological or geographical discrepancies. Sofonisba Anguissola paved the way for women to become professional artists at a time and place when this was unfathomable.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653) was an Italian Baroque painter. Her artistic reputation and merit have undoubtedly been flourishing in recent years. This is due to the discovery of her signature in many artful, emotionally charged works previously attributed to the men around her.

The most prominent example of misattribution is Gentileschi’s rendition of the story of Susanna and the Elders. In it, two depraved men spy on the young Susanna as she bathes. This revolting story has been the subject of interest for many Old Masters. Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Rubens, Tintoretto, and Veronese all depicted it with varying degrees of indifference toward the violated woman.

None of these artists managed to approach the topic with as much empathy as Gentileschi did. Her Susanna is startlingly realistic, refusing to bear witness to her own abuse. She is neither unresponsive nor submissive, as the previous imaginings of Susanna make her out to be. Gentileschi’s heroine has no patience for divine intervention. She takes charge of the situation by pushing away the lecherous men to escape their oppressive presence. The misattribution of a painting with this subject matter makes it all the more alarming.

This painting was attributed to Artemisia’s father, Orazio Gentileschi. Confirmation that it was his daughter’s painting only came in the 1990s, when literature on her began expanding. Scholars consider Susanna and the Elders as Gentileschi’s earliest work. She was just seventeen years old at the time she completed the canvas, which only fueled the theory that it was her father’s work instead of hers. It is hard to imagine a teenage girl with such exquisite talent and technique. However, Artemisia Gentileschi is notorious for surpassing expectations and breaking glass ceilings.

Specialists corrected another misattribution as recently as this past February. A painting of the biblical David and Goliath is officially the work of Artemisia Gentileschi. Conservator Majo Prieto Pedregal, working for the Simon Gillepsie Studio, uncovered the artist’s signature during conservation.

This revelation did not come as a surprise to everyone. In 1996, Gentileschi specialist Gianni Papi wrote in a journal article that he saw in the canvas her characteristic use of light and color. Nevertheless, the assumption was that it had been a painting of one of Orazio Gentileschi’s students, a minor artist by the name of Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri (1589–1655).

Its verification as a work by Artemisia Gentileschi and correction of the misattribution proved, once again, the artist’s talent and range. It also partly explains why she seems to be experiencing such a revival over 300 years after her death.

Judith Leyster (1609–1660) was a Dutch painter of genre scenes and portraits. In the 21st century, she is one of the most recognized female figures of the Dutch Golden Age. Leyster was successful during her own life too. She belonged to an artist’s union, the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, and was one of the first women to do so. Despite her artistic achievements, she had a short-lived career that she had to quit after her marriage. She then fell into obscurity and resurfaced in the late 19th century.

Most of Leyster’s works were posthumously attributed to Frans Hals, a contemporary of hers who also painted jovial genre scenes. In fact, out of her 35 surviving paintings, most were ascribed to either Hals or Leyster’s husband, Jan Miense Molenaer. Those that were not assigned to either of the two men were simply left unattributed. For the better part of 200 hundred years, it was as if Judith Leyster never existed.

There are various theories explaining the similarity between the styles of Judith Leyster and Frans Hals. Some historians posit they were colleagues, while others theorize they had a teacher-student relationship. Either way, their works are similar in content and technique. Both artists shared an informal mien and favored loose brushwork. This is, partly, what let the misattribution go on for as long as it did.

Their artistic approaches were, indeed, compatible. However, their signatures were completely different. Art dealers who obtained Leyster’s works had to manually paint over the artist’s signature and cover it up with that of Hals. What may have initially started as an honest confusion between two similarly trained artists evolved into malicious intent and fraud. Art dealers did not want to ruin the illusion and, instead, played their dutiful part in it, desperately clinging to financial gain.

Aside from her distinctive signature, where Leyster deviates from Hals is through her targeted, imposing the use of light and shade. Her encounter with the Utrecht Caravaggisti certainly influenced her experimentation with chiaroscuro and helped cultivate her distinctive style.

The discovery of Judith Leyster entails a riveting story. A conflict arose in 1893 between two English art dealers surrounding the painting The Happy Couple. In it, a young man and woman are drinking and playing music whilst in a state of euphoria. One dealer purchased the work from the other and then sold it to a customer. The buyer noticed a foreign signature and took the case to court, suspecting art forgery. The result of the investigation brought to light more than anyone could have imagined. Dutch art historian Cornelis Hofstede de Groot testified in court as an expert witness, confirming definitively that the signature found on The Happy Couple did not belong not to Frans Hals; it belonged to a female Dutch painter named Judith Leyster.

As the monetary value of the painting dropped by a steep 25%, the dealers blamed each other for the misattribution. Meanwhile, no one celebrated the discovery of the previously unknown painter. De Groot’s discovery helped track down seven more of Leyster’s works bearing her characteristic signature. Her name began gaining traction, and she is now part of mainstream art history, with major institutions dedicating exhibitions to her.

Many art historians believe that we haven’t seen the last of Leyster and that she didn’t stop painting after her marriage. We just haven’t discovered the entirety of her oeuvre yet, some of which might still be erroneously attributed to her husband.

Marie-Denise Villers (1774–1821) was a French Neoclassical painter, a specialist in portraiture, and a pupil of Jacques-Louis David. Art historians attributed to her Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes/Young Woman Drawing, a highly discussed painting only recently.

The work is a mystery in more ways than one. Its subject matter, despite what the title might insinuate, remains vague. While the young woman painting is at the center of it, she has a desolate expression. She is holding what appears to be a canvas, and she is looking directly at the viewer as if to ask for help. Behind her, we see a window with a broken glass panel. Through it, an enamored young couple can be spotted in the distance. This composition, along with the intense contrast of light and shade, creates an unsettling atmosphere for what, at first glance, appears to be a mundane portrait.

The painting’s authorship has been equally vague and debatable for centuries. Jacques-Louis David, Villers’s major influence, was the first name thrown in the authorship pool, and it is not hard to see why. The misattribution probably happened at some point after the acquisition of the portrait by the Du Val d’Ognes family. It is unknown whether or not this was deliberate. Perhaps the family wanted to boast about owning a work of the famed artist. Or perhaps it was the educated guess of someone who had studied David enough to spot the similarities but not enough to spot the differences.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired the painting in 1917. In 1951, MET curator Charles Stirling verified that the painting was first exhibited during the Paris Salon of 1801, the year when Jacques-Louis David boycotted the exhibition. This excluded him from the list of potential authors once and for all. Stirling then went on to propose that a woman had painted this canvas. Four decades later, in 1995, Margaret Oppenheimer proved him right through fastidious research of the records of Jacques-Louis David’s students. The idea that Marie-Denise Villers is the portrait’s true creator gained a following, and, as a result, one part of this painting’s enigma is no longer a mystery.

There is still ongoing interest and scholarship on it to this day. In 2011, art historian Anne Higonet argued the painting is a self-portrait of the artist, and the Du Val d’Ognes family renamed it Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes only after purchase. What supports this is that the sitter’s features resemble the way that Villers’s sister, Marie-Victoire Lemoine, also a painter, depicted her.

Regardless, this work constitutes a masterful portrayal of a young woman artist. In the last two decades, it has traveled to exhibitions throughout both the United States and Europe. The painting has managed to enchant museum-goers, even those unaware of the complicated story behind it, with its powerful energy and enigmatic composition.

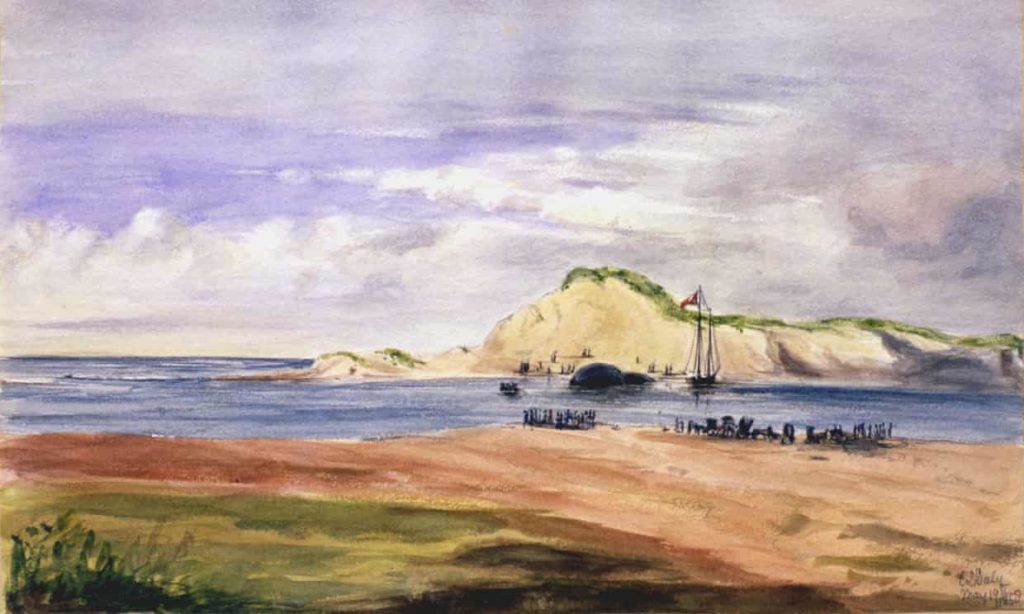

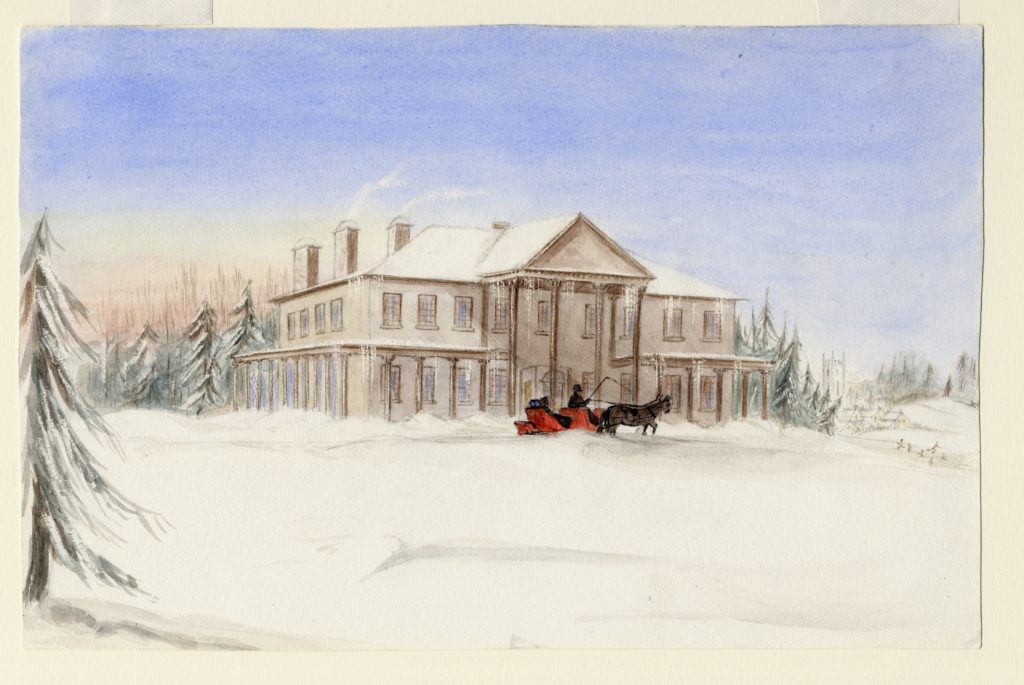

Caroline Louisa Daly (1832–1893) was a 19th-century Canadian landscape painter. Discovered in 2017, she had been hiding in plain sight for over 50 years. The gallery housing her watercolors attributed them for decades to John Corry Wilson Daly and Charles Daly.

The slow reveal of the artist’s identity began with the visit of Caroline Louisa Daly’s great-grandson, Richard Jenkins, to the Confederation Center Art Gallery in Prince Edward Island, Canada. The paintings he saw there reminded him of his great-grandmother’s canvases. He contacted the gallery with his postulation: the paintings attributed to John Corry Wilson Daly and Charles Daly belonged to a different Daly entirely. The museum staff proceeded to launch a two-year investigation into historical records to uncover the truth of his claims, and the findings astounded them.

They found that the attributions to John Corry Wilson Daly and Charles Daly were completely insubstantial. There was no evidence, other than their last names, pointing to either man being the author of any of the art hanging on the Gallery’s walls. In fact, the former was not even a painter, and the latter had never visited the real locations depicted in the paintings. After Caroline Louisa Daly’s family provided the museum with some of her works they had in their possession, the fact that the same artist was behind those canvases and the ones the Gallery owned became immediately clear.

The truth was in the details. The way that Daly portrayed windows and trees was very characteristic, according to Paige Matthie, Gallery registrar and lead researcher on Jenkins’ inquiry. In her opinion, this misattribution is “representative of a wider trend to ignore the accomplishments of women and downplay them”. She doesn’t believe the misattribution was intentional, just an accidental error with unpredictably unfortunate consequences.

Caroline Louisa Daly was self-taught and never exhibited during her lifetime. Only friends and family were aware of her keen eye for detail and her knack for architectural design. As for the artistic value of these watercolors, Matthie states that we fail to consider their sublime level of detail.

The same museum responsible for the misattribution made amends. It launched a monographic exhibition dedicated to the “unmasked” artist, “Introducing Caroline Louisa Daly”, curated by Matthie herself. It included six of Daly’s works that the Gallery already owned as well as six more donated by her family.

Caroline Louisa Daly’s works are a historical record of what Prince Edward Island looked like 150 years ago. This is something we cannot take for granted, as evidenced by the poor record-keeping that led to this misattribution. The discovery has been described by pundits as a “little feminist victory”, and a victory it is.

The reasons for the misattribution and subsequent erasure of these artists, among many others, are manifold. Yet the most prominent and obvious one is monetary gain. It is a disappointing, historical fact, still true today, that established cultural institutions significantly undervalue women’s art. The numbers remain a cause for concern. Meanwhile, collectors, galleries, and museums continually choose to exhibit the works of male artists, while women continue to be over-represented in art schools yet underrepresented in exhibition spaces. It is not for a lack of talent.

The touted inclusivity of the art world leaves much to be desired. It leaves women (particularly those not affluent enough to attend prestigious art schools or develop art world connections), their art, and their narrative completely outside of the equation. Thus, women’s stories are left perpetually untold.

The process of correcting misattributions is lengthy and exhaustive, full of bureaucratic obstacles and brick walls of records. However, as evidenced by the stories of Sofonisba Anguissola, Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Leyster, Maria-Denise Villers, and Caroline Louisa May, who are only the most prominent examples in a large sea of women artists who have been wronged by history, it is, nonetheless, a process well worth the trouble. Corrective reattribution of artworks is not only something with cultural consequences. It also has considerable socioeconomic ramifications, and it sets a positive example of rectifying historical wrongs against minorities.

C. J. Holmes, “Sofonisba Anguissola and Philip II”, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 26, no. 143, 1915, p. 181. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Brigit Katz, “Once Attributed to a Male Artist, David and Goliath Painting Identified as the Work of Artemisia Gentileschi”, Smithsonian Magazine, 2 March, 2020. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Christopher Knight, “Portrait of the Artist as a Woman: A new book crowns Sofonisba Anguissola as the first great female painter of the Renaissance”, Los Angeles Times, 17 May, 1992. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Kathleen Kuiper, “Sophonisba Anuissola: Biography”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 8 April, 2009. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Ben Luke, “Gender reassignment: how dealers tried to attribute female Old Master paintings as work by men”, The Art Newspaper, 23 January, 2019. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Roderick Conway Morris, “Acknowledging, finally, the work of women artists”, The New York Times, 18 January, 2008. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Diane Peters, “Caroline Louisa Daly Is Finally Getting Her Due”, JSTOR Daily, 28 June, 2017. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Peter Schjeldahl, “A Woman’s Work”, The New Yorker, 22 June, 2009. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

Dominic Smith, “Daughters of the Guild”, The Paris Review, 4 April, 2016. Accessed 8 Mar 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!