5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Still lifes are one of the most recurrent and well-known themes in art history. These subjects are usually representations of inanimate objects such as fruits, sumptuous bouquets of flowers, succulent feasts of food, or man-made objects such as instruments, books, or jewelry. Beyond wanting to show the opulence of the exposed elements, or as a symbol of wealth and power, still lifes could also have a more philosophical side, becoming allegories of the passage of time.

We can find the first examples of still lifes in classical Rome. Today, we have examples of Pompeii walls with representations of food as advertisements for bakeries or food stores. Some of the Domus (typical Roman houses) or villas were also decorated with frescoes or mosaics with food. In some cases, these images of baskets of fruit or other foodstuffs could act as votive offerings to the gods.

Although we find some reproductions of still life in the Middle Ages, the expansion of this genre occurred in the 17th century, especially in the Netherlands and Spain. In fact, it was in Holland that the term stilleven was coined, that is, “dormant life”. This is because these scenes represented a moment of stopped or paused time.

Initially considered a minor genre, still lifes soon became the favorite genre of the bourgeoisie. In some Protestant countries, such as Holland, the upper classes used these paintings to decorate their dining and living rooms. Coinciding with the economic expansion of the European bourgeoisie and the rise of international trade, still lifes became faithful testimonies of the purchasing power and opulence of the upper classes. These paintings also reflect the entry of exotic fruits and animals into Europe. The evolution of the still life genre also coincides with a humanistic and scientific volunteering to study nature. One of the main exponents of this genre is the Dutch painter Clara Peeters, who worked in Antwerp in the first half of the 17th century, noted for her great ability to capture reality with great detail.

This genre was also greatly developed in Spain in the 17th century. One of the greatest representatives of this genre in Spain was Francisco de Zurbarán. His compositions stood out for their simplicity of composition, hyperrealistic execution of everyday objects, and the play of light and shadow, so typical of the Baroque.

But it is not all lush nature and lavish feasts in still lifes. This genre soon evolved into vanitas. This allegorical theme refers to the inexorable passage of time that inevitably brings us closer to death – yup, very happy! The flowers, soon to wither, remind us of the transience and brevity of time. The objects that appear in the works, such as money, instruments, or jewelry, act as symbols of the useless pleasures that we leave behind.

An example of this is an artwork by the Spanish painter Antonio de Pereda, The Knight’s Dream. The jewels and coins indicate the earthly possessions that we cannot take with us, while the clock shows the passage of time. The theater mask refers to the Baroque concept of the “theater of the world”, understanding the world as a play that ends when the curtain comes down. The flowers, the most recurring element in these compositions, indicate the transience of time. The skull again recalls the presence of death that equals both rich and poor. In the painting there is also an extinguished candle, showing the fragility of life. The compositions of this sort had a moralizing role and were very often accompanied by the Latin commonplace memento mori – i.e., remember that you are going to die.

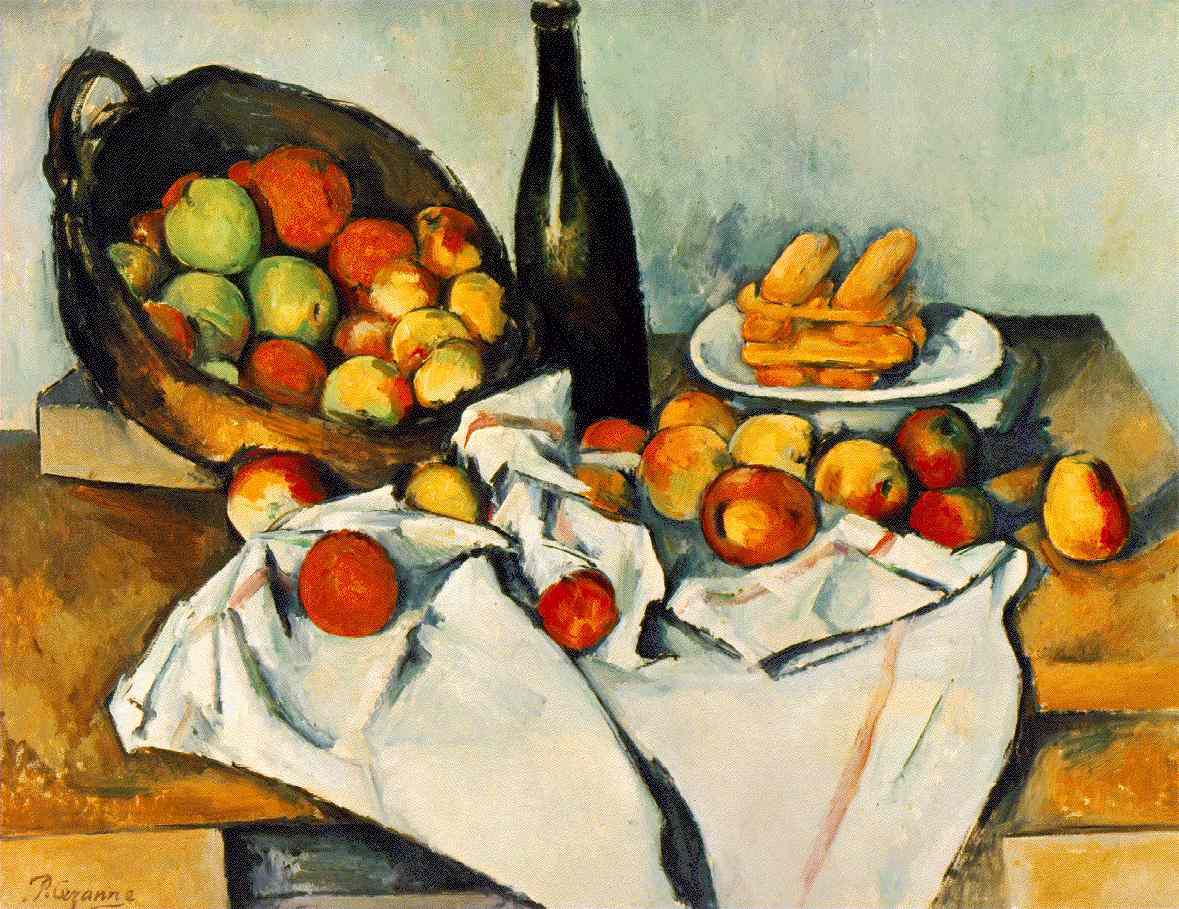

This statement of intent belongs to the French artist Paul Cézanne. And he indeed succeeded to astonish Paris with an apple! Cézanne achieved in opening a new path for avant-garde painting at the end of the 19th century. The still life shown, beyond the subject, serves Cézanne as a pretext for pictorial research. Thus, this still life is an investigation on visual perception and the decomposition of planes, highlighting the two-dimensionality of painting. This opened the way for the 20th century Cubists such as Georges Braques and Pablo Picasso. These Avant-garde painters also painted still lifes, although they were very different from those of the Baroque masters.

Still lifes are also a theme present in contemporary art! Conceptual art has also wanted to reflect on this topic. In this piece we can see a decomposition of the elements that generally make up a still life or a landscape. What could be more hyper-realistic and at the same time so ephemeral than this still life by the Catalan artist Fina Miralles?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!