The Potato in Fine Art

Do you prefer your potatoes in a landscape or in a still life or in a stew? Come with me on a tour of the humble potato in art.

Candy Bedworth 3 May 2024

Looking at a painting and getting hungry? It might be a bodegón! Here we define the genre of Spanish bodegones in the context of 17th-century European painting and acknowledge its ties to Italian and Dutch artistic schools. From Sánchez Cotán to Diego Velázquez and Francisco de Zurbarán, here is a selection of some of the most prominent painters who contributed to the development of this genre.

In Spanish, the word bodegón designates a pictorial composition in which the subject matter is an arrangement of objects. We currently associate this word with a still life depicting food items often accompanied by kitchen utensils or other household objects. However, in the context of 17th-century Spanish painting, the concept of bodegón was broader than just that of still life.

The bodegón goes beyond inanimate objects being the principal subject to include more comprehensive and complex subjects. Compositions with human figures in which objects played an important role also fell within the category of the bodegón. As we shall see further on, early works by Velázquez suggest the presence of a conceptual intersection between still life and genre scenes which add to the definition of the 17th-century Spanish bodegón.

The development of bodegones in Spain began in the city of Toledo, where naturalistic painting dominated the artistic scene. Painter and theoretician Francisco Pacheco identified Toledan painter Blas de Prado as the pioneer of this genre in Spain. Although we do not know of any conserved still life work signed by him, we can get an idea of his style through the works of his pupil Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560-1627).

In Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber by Toledan painter Juan Sánchez Cotán, a quince and a head of cabbage hang from threads apparently attached to the upper frame of a window, meanwhile a melon and a cucumber lay on the parapet. The composition is austere, with a black background and no more supporting elements than a window frame and two threads. And yet, in its compositional simplicity, this painting is deeply expressive.

All figures are painted with naturalism and great attention to detail in shape, color, and texture (see, for example, the thick leaves of the cabbage and the soft pink flesh of the sliced melon). Through this, and using light and shadows, the painter creates an illusion. From the point of view of the spectator, it looks as if the cucumber and the slice of melon are within reach. This optical effect is called trompe l’oeil (literally meaning “deceive the eye”). It was popular among 17th-century artists, particularly in the Netherlands.

Two salient characteristics of many 17th-century Spanish bodegones are the naturalistic depiction of fruits and vegetables and the use of light to create the illusion of reality. Juan Fernández, known for his nickname of labrador (farmer) due to his fondness for country life, was a painter specializing in the depiction of fruits. He was active in Madrid in the first half of the 17th century and had a particular interest in grapes, a subject which inevitably evokes the story of the painter Zeuxis written by Pliny the Elder. According to the Roman author’s account, Zeuxis painted grapes so life-like that birds flew down and tried to eat them. During the period of the Iberian Union (1580-1640), grapes were a common subject in Spanish painting, often depicted alongside alive or dead birds.

As we see in the two paintings below, Juan Fernández painted grapes with great meticulousness, indicating their state of ripeness and differentiating the varieties to which each bunch belonged. Through the contrast of light and shadows, he modeled the volume of grapes and created the illusion that some of them were juicier than others. His attention to detail bears a resemblance to northern European painting. His command of the chiaroscuro technique (light and dark contrasting) reminds of Caravaggism, which may have been taught to him by Crescenzi, a Roman nobleman who arrived in Spain in 1617 and became an influential figure of artistic taste in the Spanish court. Examples of Juan Fernandez’s work appear in the Spanish, English, and French royal collections.

The subject of pottery was also widely explored. We find many examples of local and international ceramics in Spanish bodegones. In Still Life with Artichokes and a Talavera Vase of Flowers, Antonio Ponce (c. 1608- c. 1667) depicts a bouquet of flowers of multiple colors and textures placed inside a vase of Talavera pottery. Artichokes and leafy branches of apples and pears lay at the sides of the vase. The scene is completed by two butterflies flying around the flowers. The vase is very carefully painted, showing the effect of light slightly falling on its decorated surface.

In addition to its unique beauty, the ceramic produced in the city of Talavera de la Reina has a deep historical and cultural value for the Hispanic world. King Philip II ordered its use in the decoration of the Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. The artisanal techniques of its production were transmitted to Mexico during the process of expansion of the Spanish Empire. In 2019, UNESCO recognized the process of making Talavera pottery as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Mexico and Spain.

Valencian painter Tomás Hiepes (or Yepes) (1610-1674) was a specialist in still lifes. Two of his works, Delft Fruit Bowl and Two Vases of Flowers and Still Life with Ceramic, have some elements in common; for example, both of them depict a large bowl of Delft ceramic filled with apples, pears, and plums. The first one stands out for the symmetry of the composition. The bowl is flanked by two sumptuously decorated vases of equal size and motifs, both of them filled with aromatic orange blossoms which are typical of spring. In the second one, the bowl appears against a landscape background, which makes the composition of this bodegón very peculiar. The inclusion of landscapes in the bodegones is a sign of influence from Neapolitan painting. More examples of this in Hiepes’ oeuvre are found in the private collection of the BBVA bank.

In the 17th century, the Dutch city of Delft was known among travelers for the artisanal production of a type of ceramic that imitated blue-and-white Chinese porcelain. Delft ceramic also appears in Dutch Golden Age painting. Some examples are the tiles in Vermeer’s The Milkmaid and Lady Standing at a Virginal. Delft ceramic, also known as Delft Blue, continues to be produced in the city according to traditional methods.

This selection would be incomplete without some works made by two geniuses of Spanish painting who did not specialize in bodegones, but contributed significantly to the development of this genre: Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) and Francisco de Zurbarán (1598- 1664).

Diego Velázquez was a Sevillian artist famous for his role as court painter of King Philip IV. In his youth, he painted religious subjects and scenes of daily life in Seville. His early works, such as An Old Woman Cooking Eggs, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, and The Waterseller of Seville, evidence an admirable technique. He popularized the bodegón in the broad sense of the term, and his skill for this genre of painting was recognized by his master Francisco Pacheco, as well as by many subsequent scholars.

Pacheco held Velázquez in high esteem and later became his biographer and father-in-law. In his book Arte de la Pintura (1649), he argued against the low status given to the bodegón in the 17th-century hierarchy of genres with the following words:

Well, then, should still-lifes not be held in high regard? Of course they should, if they are painted as my son-in-law paints them, surpassing in that genre every other painter without exception.

Francisco Pacheco, Arte de la Pintura, 1649

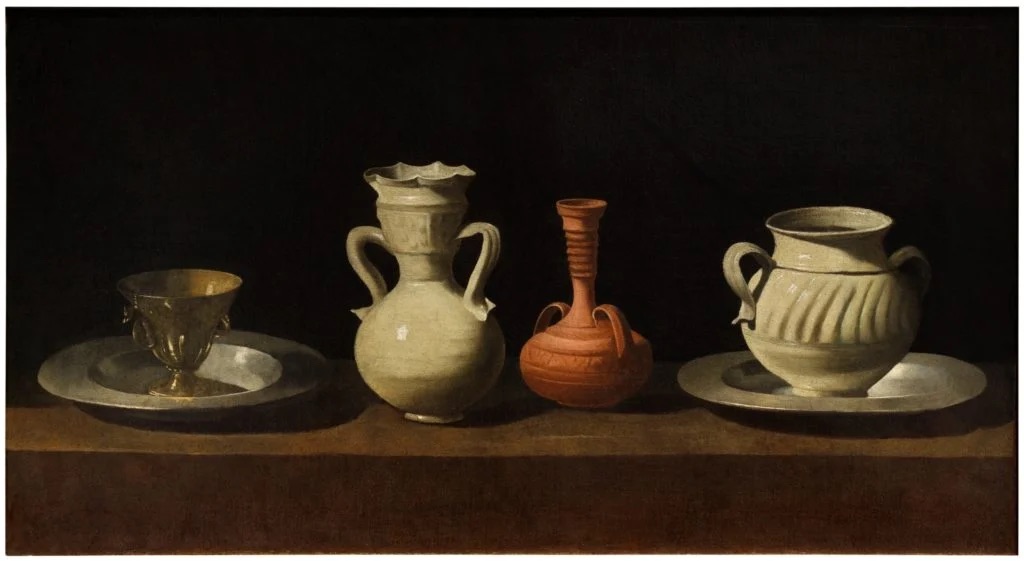

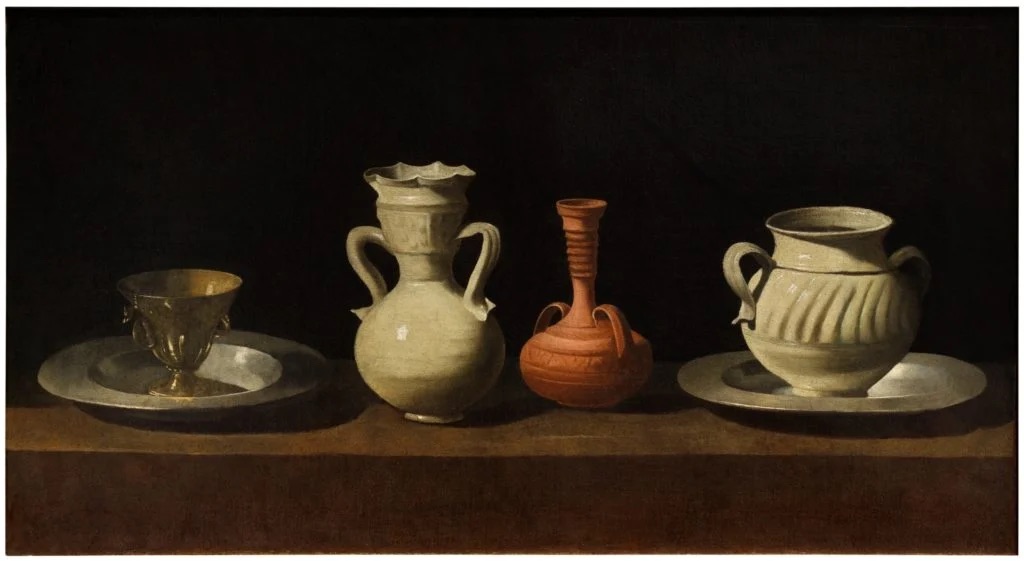

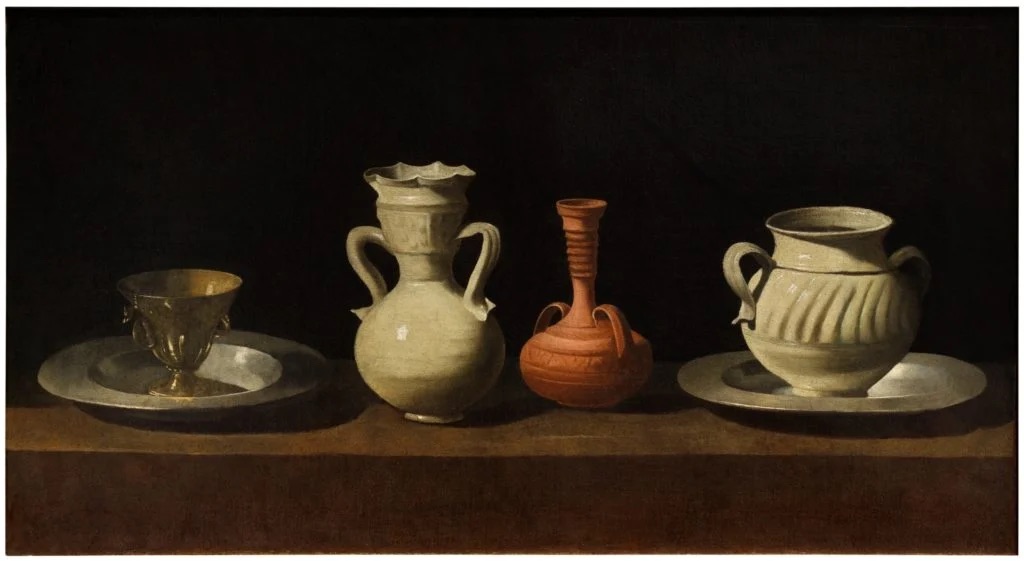

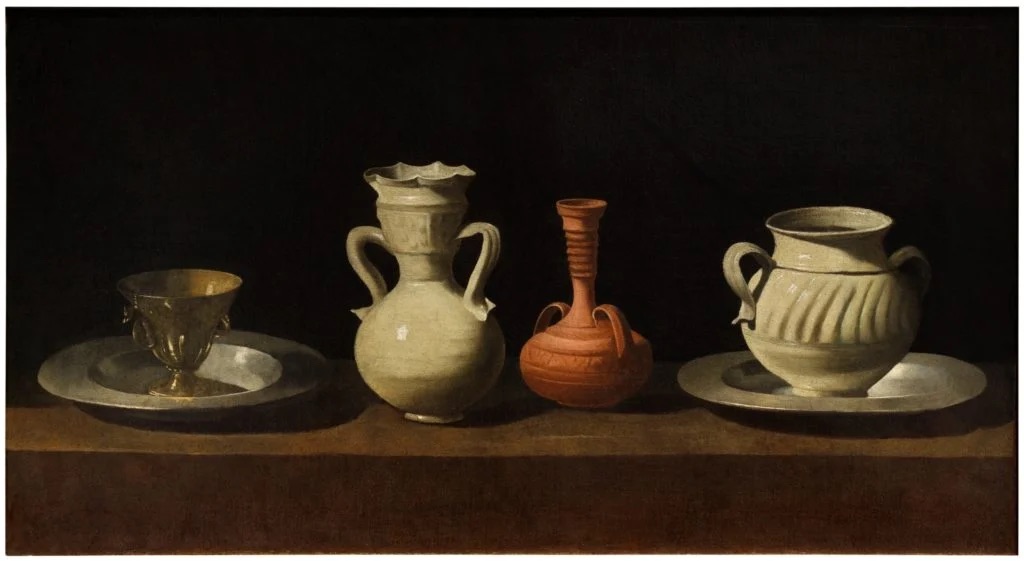

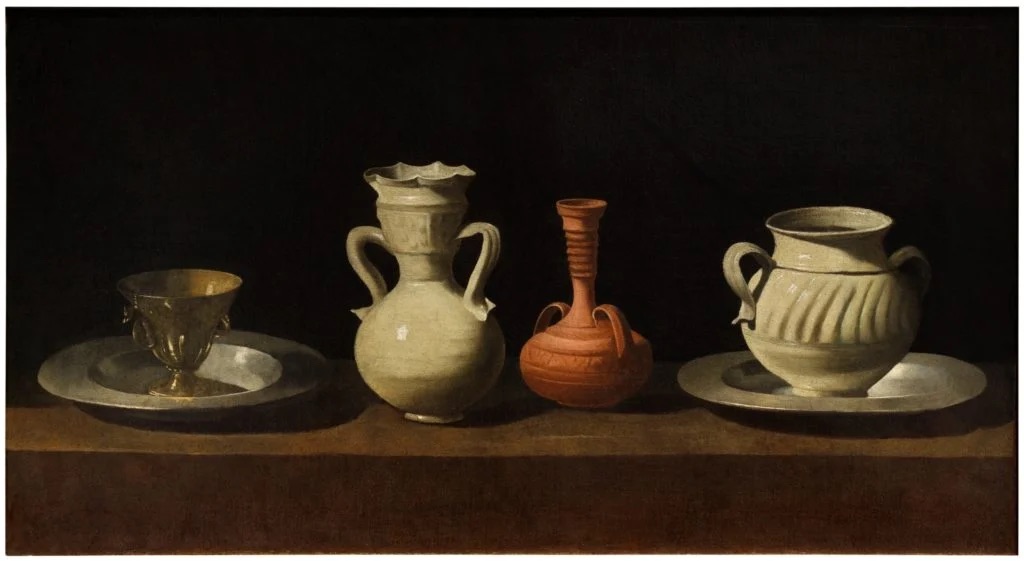

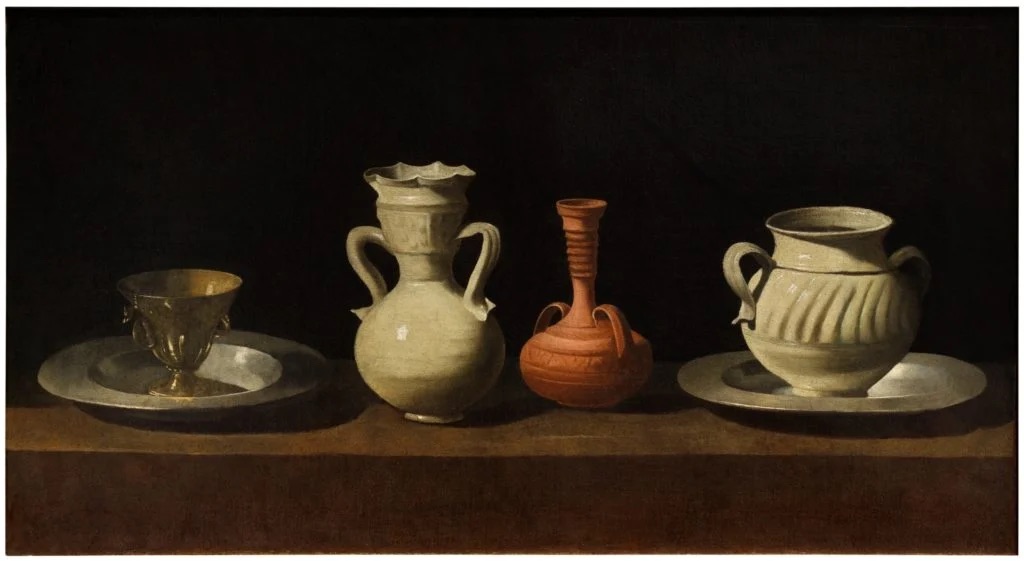

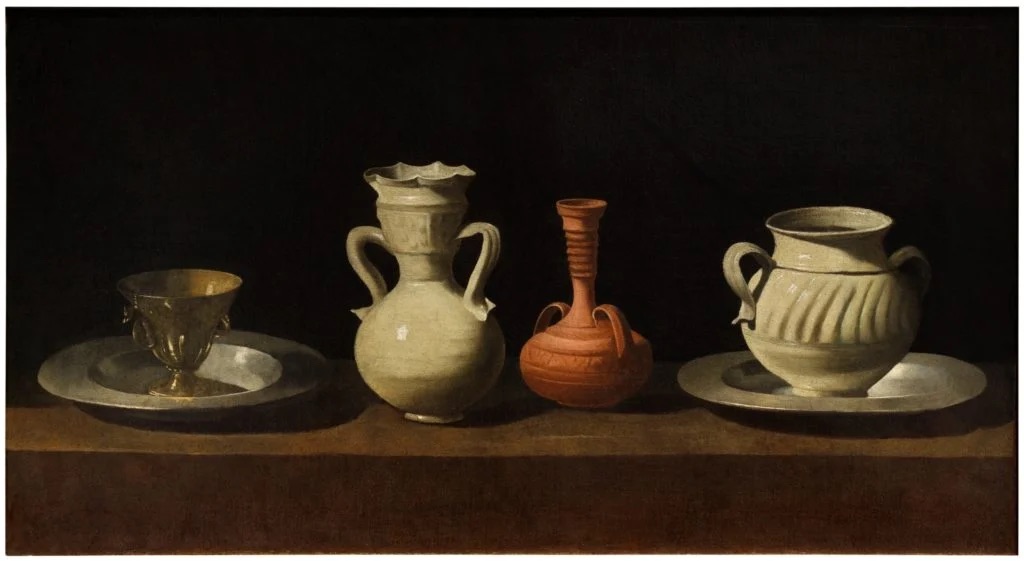

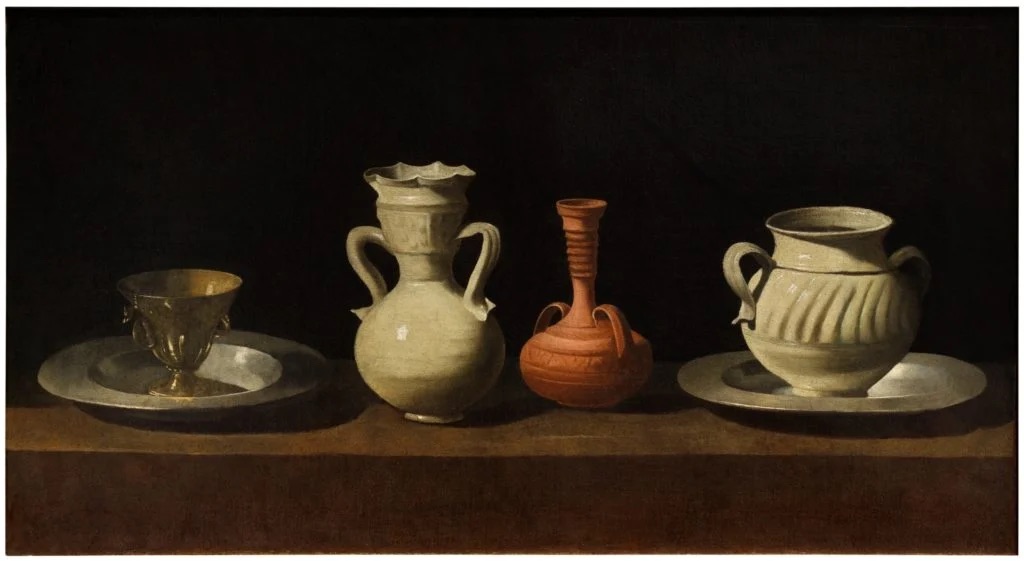

We end this article with perhaps the most famous depiction of pottery in a Spanish bodegón: Still Life with Vessels by Francisco de Zurbarán, another painter best known for his religious subjects. This painting shows four pots of diverse characteristics and uses.

From left to right, we see an elaborate bernegal (wide cup) resting on a salvilla (tray on which glasses or cups are placed) made of pewter; an alcarraza trianera (a recipient made of Triana pottery and used to keep water cool through evaporation); a búcaro de Indias (a pot from the Spanish territories in the Americas, probably from the Viceroyalty of New Spain); and another alcarraza trianera resting on a pewter dish. Through the use of light, the painter highlighted the different volumes of these objects. As the catalog entry for this work in the Museo del Prado expresses, Still Life with Vessels is a unique painting which transmits the ideas of timelessness and silence.

Spanish bodegones as a genre with the characteristics that we describe in this article occupy a prominent place in European 17th-century painting. As mentioned above, they received influence from Italian and Dutch artistic schools. But at the same time, they were undoubtedly original thanks to the peculiarities of Hispanic culture and history. An interesting topic for research is, for instance, the depiction of objects from the American colonies in Spanish still lifes. After the Baroque, the tradition of painting still lifes or including elements of still life in a wide variety of compositions acquired novel forms. Artworks by Cubist painter Pablo Picasso and surrealists Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró are telling examples of the timelessness of the bodegón.

Ángel Aterido, La nature morte espagnole, Exhibition catalogue, BOZAR, Brussels (Feb 2018–May 2018).

Francisco Calvo Serraller, Obras maestras de la colección BBVA. Pintura española de los siglos XV al XX, Exhibition catalogue, Museo Pedro de Osma (Jul 2004–Sep 2004).

Delft Fruit Bowl and two Vases of Flowers, Museo del Prado Online Collection. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Four Bunches of Hanging Grapes, Museo del Prado Online Collection. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Enriqueta Harris, Estudios completes sobre Velázquez, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, 2006.

Juan Sánchez Cotán, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Irina Moreno, The Spanish Bodegón of the Golden Age. Social significance of food and objects in 17th century Spanish still lifes. Dissertation for the Master’s Degree in Fine and Decorative Art. Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, 2013.

Francisco Pacheco and Antonio Palomino, Lives of Velázquez, Pallas Athene, London, 2018.

Still Life with Ceramic, Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia Online Collection. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Still Life with Four Bunches of Grapes, Museo del Prado Online Collection. Accessed May 26, 2020.

Still Life with Vessels Museo del Prado Online Collection. Accessed May 26, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!