The Myth of the Minotaur: Monster or Victim?

Greek myth tell us that brave warrior Theseus kills the monstrous Minotaur in a labyrinth. But who is the villain here?

Candy Bedworth 27 June 2024

The Thera wall paintings (Santorini) reveal the bustling civilization that existed on the southernmost island of the Cyclades circa 1600 BCE. Around that time the island suffered a devastating earthquake along with a volcanic eruption which caused part of the island to submerge into the sea. It is believed that the tsunami that followed reached Crete, and wreaked havoc there as well. Akrotiri, a harbor town on Thera, was preserved as if in a time capsule, buried in layers of pumice and volcanic ash. In 1967, Spyridon Marinatos began excavations in the “Pompeii of the Aegean”, unearthing multi-storied buildings that housed magnificent frescoes.

The Thera wall-paintings from Akrotiri are distinguished by the originality of their iconography, the freedom in the design and rendering of the figures, and the richness of their colors. Their perfect state of preservation, thanks to their burial in volcanic ash, has allowed the identification of several different artists working within a Theran tradition under the influence of Minoan Crete.

The stone walls were first covered with a mixture of clay and straw in order to seal the wall against moisture and guarantee the endurance of the frescoes, then came layers of plaster. The painter applied the colors to the wet surface using twine and a pointed tool. Painting on a wet surface also enhanced the endurance of the work. Lastly, some details were added on a dry surface.

The wall painting of spring is the only one that was found in its entirety, covering the three walls of a room. It shows the Theran landscape before the volcanic explosion. Upon the rocky landscape, red lilies with yellow stems bloom and sway in a gentle breeze. In the sky, swallows alone or in pairs play, announcing the coming of spring.

Two young boys are locked in a boxing match. Their tanned bodies inform us of their gender. The boys are naked apart from a loincloth and boxing gloves. Their heads are shaved, apart from a few long locks. The blue space on their heads suggests the shaved parts. The boy on the left wears an impressive amount of jewelry, a necklace, a pair of earrings, and an anklet, probably to show his higher social status.

In the same room as the boxers, the other walls were decorated with images of antelopes. Alone or in pairs, the animals are represented with thick black lines on a white background. Τhe antelopes along with the boxers form a larger symbolic composition of young humans and animals.

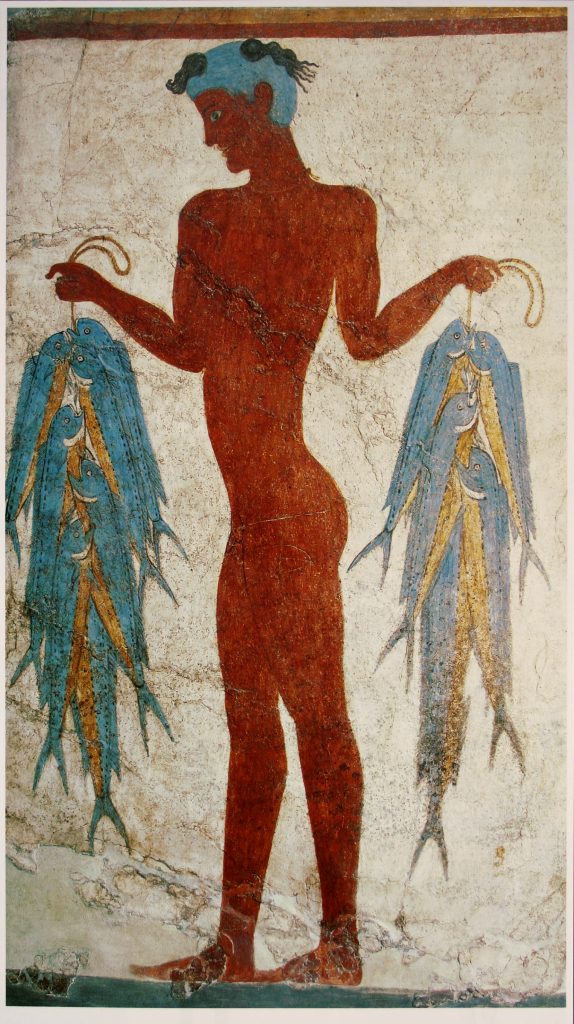

A young man is holding two batches of fish in each hand, tied with yellow string. He is tanned and his head is shaved like in the fresco of the boxing children. The fisherman fresco was found in the northeastern corner of room 5 in the West Ηouse. There have been suggestions that he is performing some kind of ritual because we see him move towards the northwestern corner of the room where excavations unearthed an offering table.

It is possible to distinguish the hands of different painters in the Theran wall paintings. The austerity and simplicity of the fisherman, balanced with grace and vitality in the design of the figure, resembles that of the boxing children. Perhaps both frescoes were made by the same hand.

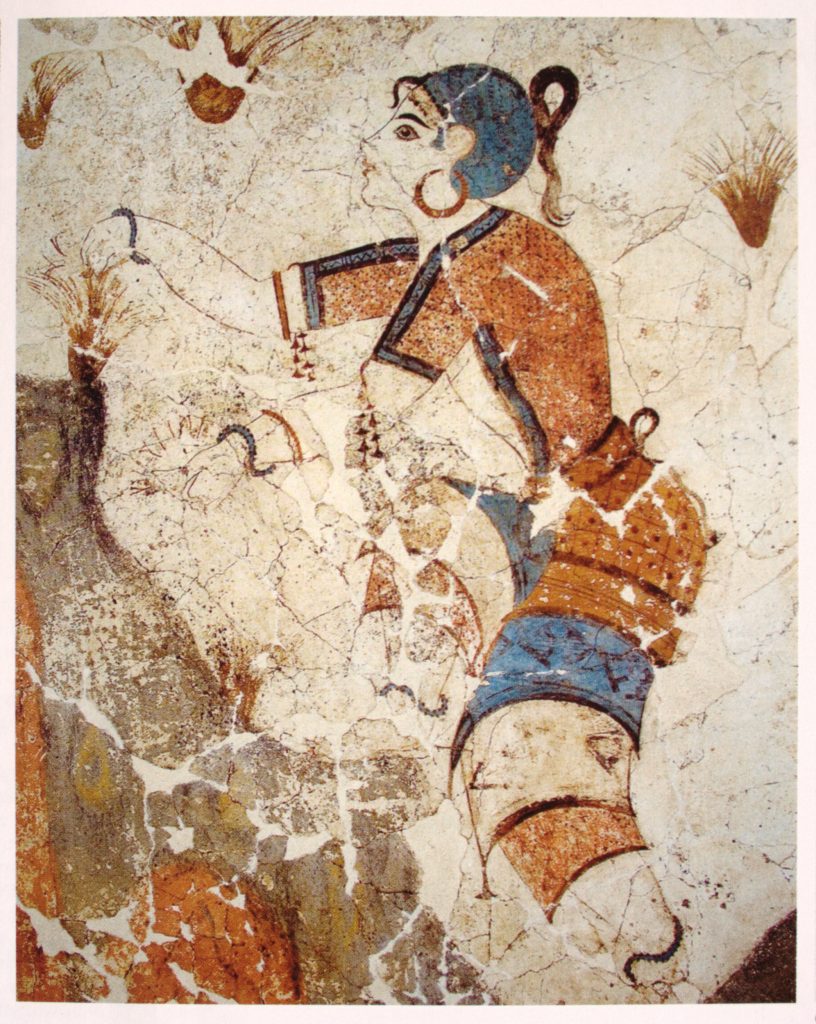

Saffron is one of the most delicate and interesting ingredients to cook with and has been since the times of prehistoric Thera. In this fresco, two women gather the plant from the rocky landscape. There seems to be a difference in age and status between them. On the left, there is an older woman, possibly the teacher. She gathers the saffron using only one hand while holding a basket. On the left we see a younger woman, the apprentice, using both hands. Because of the stern expression on the teacher’s face, she is probably reprimanding her apprentice for her sloppy technique.

Both women are painted with white alabaster skin, a symbol of their sex, to show that, in contrast to the men, they do not spend much time under the blazing Greek sun. Their clothes and jewelry are ornate and beautifully designed. The landscape and the figures are handled freely and more painterly, reminding us of the ‘Spring’ fresco and suggesting that both came from the hand of the same painter.

In a playful scene, a troop of monkeys is quickly climbing the volcanic rocks of the island to get away from two dogs. The fresco is fragmented but the cheerful and colorful animals still fascinate the viewer. Monkeys were not indigenous to the island. However, monkeys must have lived on the island before the explosion, possibly imported from the Middle East or North Africa, because during the excavations, a monkey’s skull was found.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!