Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

The biblical figure of David, the young shepherd who defeated Goliath, was a popular subject for sculptors during the Renaissance. However, no representation of this tale achieved as much fame as the one made by Michelangelo Buonarotti. This one is special for quite a few reasons.

Michelangelo is known to be one of the greatest artists of all time. He was a painter, sculptor, poet, and architect. He was also a major workaholic and was busy until the end of his 89 years of life. Called “the divine” by his contemporaries, he left us masterpieces such as the Sistine Chapel, the Pietà, and (of course) the beautiful David.

Unlike other sculptors, Michelangelo posed his David before the battle. While the Davids of Donatello and Andrea Verrocchio stand victorious over the enemy’s head, this one has not fought yet. This is the hero before action, the one getting ready for the fight ahead.

Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photograph by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The story of David is that of the Biblical hero who defeated Goliath and thus saved the Israelites from the Philistines. With a sling and a stone, the unarmored young shepherd hit Goliath in the head, making the giant fall and then decapitating him.

The tall figure sculpted by Michelangelo stands in contrapposto, an asymmetrical pose that results from a weight shift to one leg. Here, his weight is shifted to the right leg, and a tree stump supports behind it. Completely nude, David’s only weapons are a sling (over his left shoulder) and a rock (hidden in his right hand).

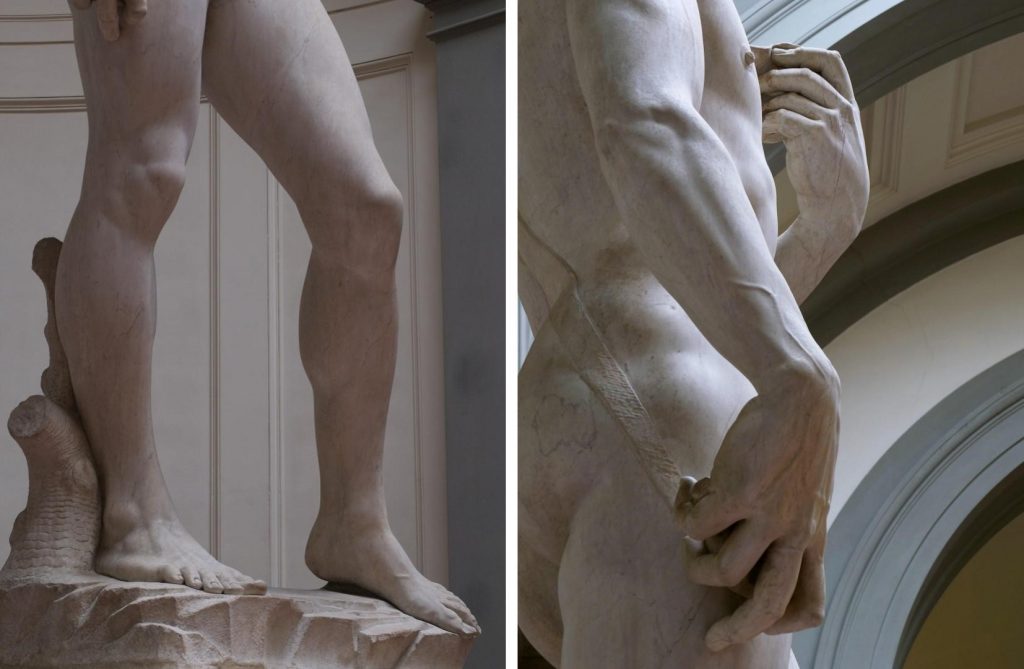

Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504, details of legs and arms, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photograph by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

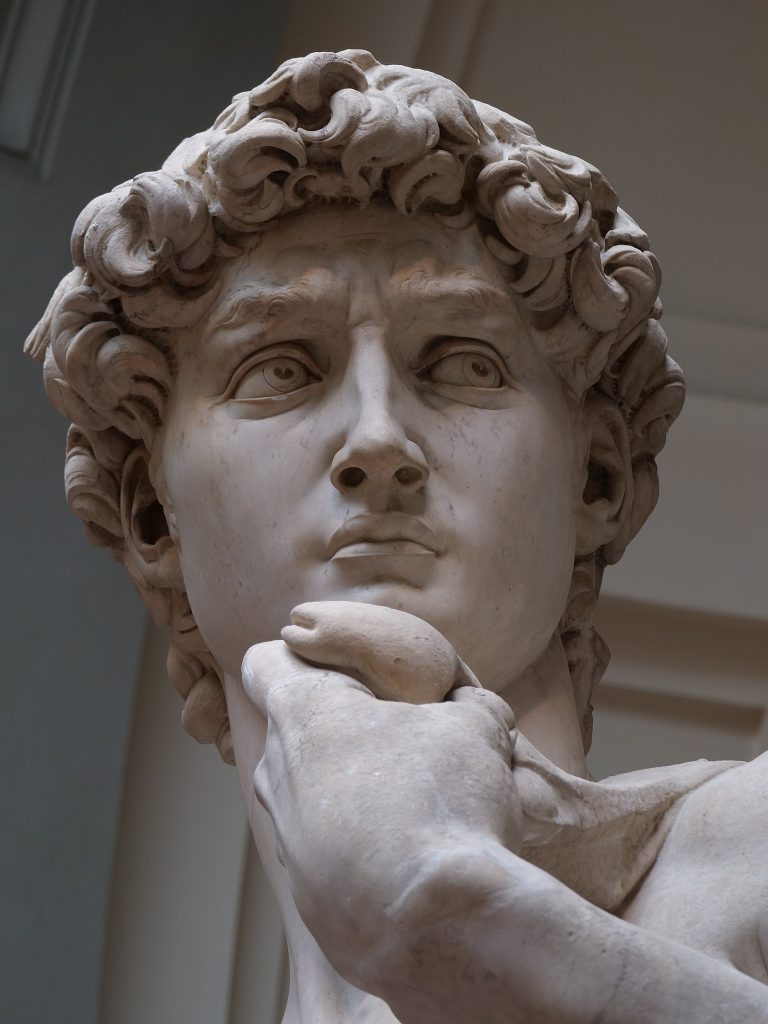

This pose is a seemingly relaxed one, but the anticipation of battle is represented in the details. His body and facial expression signal what is about to happen. His head is turned at three-quarters, brows furrowed, and nostrils flared. There’s tension in his body – as can be seen in the tense neck, taut musculature, and defined pulsing veins. David has a calculated gaze, and the carved-out pupils add intensity to it.

Michelangelo, David, details of face and hand, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photographs by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

He is prepared, and his body suggests the imminence of movement. It’s a surprisingly dynamic image (considering this is a rigid sculpture made of inert stone). The diagonals from the shoulders, waist, and hips create an S figure that adds to this perception.

Michelangelo, David, view from below, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photograph by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The sling and the rock are kind of camouflaged in the marble body, barely noticeable – they are not the focus here. The statue personifies not only the aesthetic of the High Renaissance (based on the rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman culture) but also one of its ideals.

This David is focused on the challenge ahead, thinking hard, and analyzing the situation. It’s an image of rationality and thus the embodiment of the Renaissance ideal of a man. His victory is not based on brute strength: this is a hero with skill and reason. So even if this is the image of a highly idealized muscular and strong male body, the emphasis is not on physical force but intellectual strength.

Michelangelo, David, face detail, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photograph by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The block of marble used to give life to Michelangelo’s David was a challenge in itself. At least three sculptors had already tried carving it, each of them leaving the block in even worse conditions than before. Marble is best carved when fresh out of the quarries before age and exposure makes it harder to control. The block got more weathered, resistant, and thin after each new attempt to shape it.

Called “the giant,” the enormous piece of stone had been abandoned for over 40 years when Michelangelo started working on it. It was considered flawed and too narrow to be used. Much of Michelangelo’s composition actually results from what was possible of the marble piece he used. How slender the man is and the position of his members, for example, were deliberate decisions to ensure the sculpture would fit the narrow and previously chiseled marble.

Michelangelo, David, side view, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photograph by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The artist started working on “the giant” in September 1501 and completed his David almost three years later. To access all parts of the enormous block, Michelangelo had to build a scaffold of at least three levels. Just like David defeated Goliath, Michelangelo managed to conquer the challenging block of marble that others before him had been unable to use. From a piece of abandoned and flawed stone, he brought one of the masterpieces of Italian art to life. As usual in Michelangelo’s works, the anatomy is especially astonishing.

Michelangelo, David, details of the musculature, 1501–1504, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy. Photographs by Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Without any doubt, this figure has put in the shade every other statue, ancient or modern, Greek or Roman.

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Michelangelo was 26 years old when commissioned for this work. It was a huge honor for such a young artist – at this point, he had not yet achieved the everlasting fame we know of, but it was precisely this work that changed that. With his David, the sculptor achieved lasting fame and, as valued by his father, gained “honor at home.”

The sculpture was commissioned to be placed over 12 meters above ground, decorating the outside of the Cathedral of Florence. That it was sculpted to be seen from a distance explains both its size (over five meters tall) and its disproportionally large head and hands. When a replica was placed that high above the ground, the proportions made much more sense to those viewing it from down under. The original sculpture never occupied its place in the cathedral, though.

Replica of Michelangelo’s David outside of the Cathedral of Florence, Florence, Italy. The History Blog.

There’s no certainty on why a new location was proposed. Perhaps it was considered too fabulous to be placed so high up and far from the public. In 1504, Michelangelo’s David was placed on a platform in front of the Palazzo della Signoria (the seat of government in Florence), more known as Palazzo Vecchio. It stayed there until 1873 when it was transferred to its current location in the Galleria dell’Accademia of Florence in order to avoid further deterioration. A replica occupies the original space in front of the Palazzo Vecchio since 1910.

This sculpture is not only artistically impressive (an achievement from a young artist), but it is also significant in its social and political context. It’s interesting to notice that the sculpture was removed from the original religious context into a secular one. Instead of taking its place in a cathedral, the David was placed where it could symbolically guard the city. The statue became a potent political symbol.

Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy. Photography by Arnaud 25 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

At this moment in Florence’s history, the city was trying to re-establish itself as a Republic. It had run the Medici off in 1494, and Girolamo Savonarola was executed in 1498. With all this happening, the biblical figure of David held special significance for the people of Florence. They identified with him—a hero of exemplary strength and courage who managed to defeat the enemy.

More than a beautiful artwork representative of an art period, Michelangelo’s David was also a symbol of the Florentine Republic. It was such a strong image that, at some point, stones were thrown at it by supporters of the Medici. It survived, though, and over 500 years later, it continues to be a compelling image representative of its time.

Christof Thoenes, Frank Zöllner, and Thomas Pöpper, Michelangelo: Complete Works, Taschen, 2009.

William Wallace, Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man, and His Times, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Steven Zucker, and Beth Harris, Michelangelo, David, in Smarthistory, December 6, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!