Masterpiece Story: The Rainbow Portrait

Queen Elizabeth I is known throughout history as one of the most famous British Queens. Even without a husband, she successfully ruled England for 45...

Anna Ingram 8 July 2024

The Pietà – or Virgin of Pity – is the representation of the Blessed Virgin holding her divine son on her knees. This iconic type entered Italy after having spread to France and in Germany from the 14th century. The most famous of these Virgins of Pity comes from the genius of Michelangelo Buonarroti, who was only 23 years old at the time of its creation. Commissioned by Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, French Ambassador to Rome, this work is sculpted from high-quality Carrara marble, chosen by Michelangelo himself. This work is now preserved in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Above all it represents the ultimate union of a mother and her only child.

The sculpture, made in just one year, appears as the highest expression of purity, both through the choice of divine figures – the Virgin and Jesus Christ – and through the artist’s smooth touch, made possible by the most careful polishing. Executed with extreme refinement down to the smallest detail, this Pietà is the very manifesto of Michelangelo’s artistic harmony and technical precision. The pyramidal structure tempered by the serpentine shape of the body of Christ balances the composition. The abandonment and inert relaxation of Jesus are opposed to the calm verticality of the figure of his mother. She personifies meditation with her gesture – an outstretched hand, open palm – and voluntarily offers her child to God.

This masterpiece certainly illustrates pain, but it seems that there’s no sadness in it. The peaceful features of Jesus evoke no suffering and those of the Virgin bear witness to the acceptance of the divine sentence. Both present and absent, the Virgin reveals through her gentle face, the interiority of her being. She materializes the universal character of compassion. Love is at the heart of the work; the power of maternal love is deeply linked to the grace of love devoted to God.

Did you notice the timeless dimension of this artwork? Indeed, the holy woman and her son seem to be the same age. Michelangelo himself explained this detail: he desired that Mary must “appear eternally virgin, while her son, who has taken on our human nature, must be, in the stripping of death, a man like the others”. In this work, Michelangelo puts beauty in the spotlight, so that it outweighs suffering. In other words, aesthetics are at the service of the spiritual in order to better illustrate, through this timeless beauty, the mystery of the Passion.

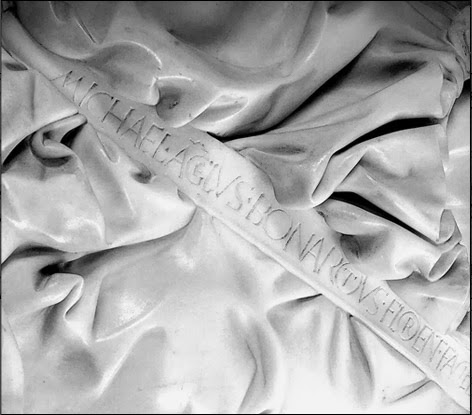

The strength of this work also lies in its history. As soon as it was installed in the Santa Patronilla chapel of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, it underwent the first modification, by the hand of its creator himself. Indeed, following the public exhibition of the Pietà, Michelangelo was offended by the fact that only a few visitors attributed the authorship of the work to him (it initially remained anonymous). The artist thus decided to add his signature to a ribbon adorning the breast of the Virgin: “MICHAEL. ANGELUS. BONAROTUS. FLORENT. FACIEBAT” (“Creation of Florentin Michel-Ange Buonarroti”). So, the Pietà remains to this day the only work of art signed by Michelangelo.

Furthermore, when the statue was moved in the 1700s four fingers of the left hand of the Blessed Virgin were broken and later restored by Giuseppe Lirioni in 1736. This accident turned out to be minimal in the face of the violence suffered by the work on May 21, 1972. On that day – the day of the Pentecost – a geologist hammered the Pietà, inflicting about fifteen blows with a hammer. The left arm and the nose of the female figure were broken, while the eyelid and cheek were also damaged. With the help of marble powder and invisible glue, it took ten months to restore the sculpture. Now protected by bulletproof glass, Michelangelo’s Pietà has regained its majestic place in the heart of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Finally, this Pietà, the fruit of a deeply lived and sometimes painful faith, remains the image of the spiritual force that tears itself away from matter, wrought by Michelangelo’s desire for eternity.

“How could a craftsman so divinely accomplish such an admirable work in such a short space of time? It is a miracle that a shapeless rock has achieved such perfection that nature only so rarely models it in the flesh.”

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!