4 European Events Harmonizing Art, Nature, and Techno Music

Techno and electronic music have always shared an intimate relationship with art, intertwining rhythms, beats, and melodies with visual expressions...

Celia Leiva Otto 30 May 2024

Big ones, small ones, round ones, flat ones, pointy ones, pendulous ones, young ones or old ones, we love them all! Boobs are important and have been celebrated throughout the history of art for thousands of years. We’re going to take a look at a selection of the best boobs in art history, to honor those who have been afflicted by breast cancer; those who carry out research and strive to find ways to save lives; carers, and those who have lost loved ones.

There are so many boobs to choose from, so let’s begin with the best boobs in early art history. The Venus of Willendorf is a Paleolithic figurine that is 25-30,000 years old and is made from limestone that was once stained with red ochre (traces remain). She is named after the town in Austria where she was found, although she is not made from a material that is found in that area.

Standing at a fraction over 11 centimeters she is tiny but her potential meanings are powerful. Some possibilities are that she is a fertility figure, a mother-goddess figure, or a totem perhaps for good fortune (again perhaps in terms of fertility). Her belly and hips are fully rounded and her hands rest gently on her ample breasts. There are no facial features but instead a full covering of coiled hair. Her legs recede away below her but no feet are present. The fertility of the land and the people who live in it are essential for survival: her full figure perhaps hints at the abundance longed for by the people of that time.

This lady is a little bit younger than the Venus above. She was discovered in Çatalhöyük in southern Anatolia, Turkey, and dates from c. 6000 BCE. She bears many similarities to her older counterpart, but she is made of clay and is taller (16.5 cm seated).

Again, we see an extremely womanly figure: full thighs, breasts, and arms plus an exaggerated belly – all features seen as indicators of fertility. She is seated between two big cats (possibly lionesses or leopards) which act as symbols of her power as an earth mother or fertility goddess figure. It is thought by some that she may be in the process of giving birth. She was discovered in a grain bin!

Artemis of Ephesus, also known as Diana of Ephesus or the Lady of Ephesus, was another ancient Phrygian (Anatolian) earth mother or fertility goddess figure. This version of her dates from the 1st century CE and is a Roman copy of her form, but her original conception is much older. It is thought that the original city of Ephesus might have dated as far back as the 10th century BCE.

It is clear that she represents the fertility of nature: her lower body is adorned with animals, flowers, and other symbols, and she has not just two boobs but dozens of them. She certainly has her fair share of the best boobs in art history! Later the Ephesian Cult of Artemis spilled over into both Greek and Roman culture, and so there is considerable crossover between the later Diana/Artemis and this earlier one.

Other early goddesses were associated with the Lady of Ephesus too, for example, Cybele. Cybele was also an earth mother, often depicted wearing a mural crown and riding in a chariot drawn by lions. Perhaps the much earlier Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük is her forerunner? It certainly seems likely. Lions are symbolic of power and strength, and a god or goddess for whom they are an attribute is therefore endowed with their qualities. A strong fertility goddess was equal to a good harvest, healthy animals, and a radiant society.

Dating from the Hellenistic period (323-31 BCE), the Venus de Milo was discovered in a hidden cavity on the Greek island of Melos in 1820. She is believed to be Aphrodite, the goddess of love (the Roman equivalent is Venus). Other scholars however believe her to be Amphitrite, the goddess of the sea and wife to Poseidon. She would have originally worn jewelry: there are holes present to fix a headband, bracelet, and earrings. What form these took we can only speculate. Some also think that she may at one time have held objects in an outstretched hand, for example, an apple or a crown.

She has a typically elongated torso and small breasts which are common in sculptures from this period, and overall, the effect is much more athletic than our previous three Venuses. The drapery appears to be tumbling down around her, held up only by one bent knee, yet her face is one of confidence and purpose. She is performing an action, perhaps of showing or giving, and her mind is on this rather than on her nakedness. Her gaze seems to me to be firmly directed, and given that she is six feet eight inches tall, I would certainly take her seriously if she was directing it at me! She is confident, strong, and purposeful, and definitely has some of the best boobs in art history.

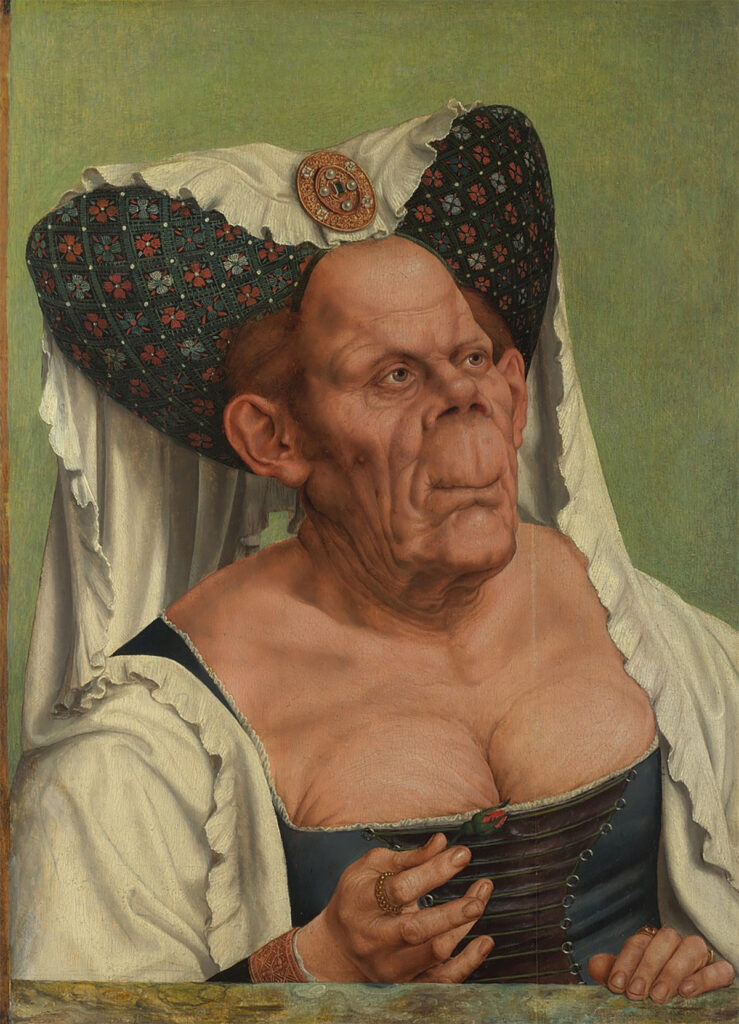

In around 1513 Quentin Massys, a Flemish artist set out his painting tools and committed to paneling one of the most beautiful, ugly paintings of the Renaissance period. An Old Woman breaks the rules when it comes to conventional depictions of the feminine: she is warty, sagging, and inappropriately dressed for her age. In short, she is grotesque: there is nothing fertile or abundant about her except perhaps her struggle with reality. There is a duality in this painting though: while her features appear to mock, even dissolve conventional forms and transform them into monstrous ones, she is painted with such a high degree of realism that it is impossible not to admire her whilst simultaneously being repelled. I think we should be grateful to Massys that she is not naked like our other Venuses because she possibly has the worst boobs in art history.

An Old Woman is a secular allegory rather than a portrait, undermining conventional ideas of feminine beauty by employing satirical and grotesque elements in order to sermonize. Her complete ugliness immediately associates her with an immoral life. The offering of a rosebud symbolizes a gesture of love, which is sadly laughable and parodies the engagement portraits of the era. The rose implies further meaning through its associations with the Virgin Mary and the goddess Venus where it denotes sinlessness and love respectively.

Painted c. 1615 by Peter Paul Rubens the Discovery of the Child Erichthonius takes us back to the theme of fertility. The painting refers to the story of Vulcan (Hephaestus) who pursued Minerva (Athena) in order to “ravish” her. Disgusted she fought him off and his semen fell on the ground. Erichthonius sprung from this union between Vulcan and the Earth. Minerva first entrusted the three daughters of Cecrops (the King of Attica) to take care of the baby with strict instructions not to open the basket in which he lay, but this failed and so Erichthonius was raised by Minerva herself.

In the painting we see the three voluptuous daughters giving in to their curiosity. Set back on the left there is a statue of Pan, the Greek god of woods and fields. On the right there is none other than Artemis of Ephesus depicted as a fountain, making the number of boobs in this painting exactly 13 – a perilous number even as far back as the Ancient Greeks. If you read the story here, you’ll see why six of these art history boobs might not be so lucky!

The Madonna Litta was painted by Leonardo da Vinci (although this is contentious) c. 1490. In the vast canon of iconography centering on the Madonna figure this particular rendering is a devotional form known as Madonna Lactans (nursing Madonna). The scene is one of harmonious, idealized motherhood.

There is an atmosphere of pure contentment: blue skies in the background, soft light, and the gentle gaze of a mother feeding her baby. There is no breastfeeding shame to be found here. Anyone who has tried to breastfeed only to have the manager of the establishment banish them to a tiny toilet cubicle will know exactly what I’m talking about! A Madonna Lactans in this context is probably the ultimate representation of what boobs are really for. Once again it speaks deeply of nourishment, fertility, growth, and health. This is not something to be embarrassed about: it is something to celebrate.

Looking more closely, and past the best boobs in art history angle, the Christ child does not return his gaze to his mother, although he does cradle her breast with his right hand. Instead, he gazes almost out to the viewer but seems absent-minded and unfocused. This is an indication of what is to come. Already he is pulling away toward the destiny with which we are all familiar. This is confirmed by the presence of a chaffinch which he holds in his left hand, representative of the soul as it departs the body in death.

It surprised me to learn that breast cancer is depicted in art as far back as the 16th century. I was surprised not because I thought that breast cancer didn’t exist then, but more because I would not have expected an artist to include it in his ideal representation of the female form. Of course, many artists certainly did paint figures “warts and all”, especially those artists of the Northern Renaissance. This painting however is Italian, which is also maybe why it seems so anomalous that this kind of physical aberration has been included.

Another reason for my surprise is that “looking” when it comes to the female body tended to be for the attention of men: women were to be consumed, even if innocently. Something about the inclusion of a wonky, afflicted boob – malignant breast cancer in fact – on this beautiful female figure feels both brutally realistic and respectfully appreciative at the same time.

In a kind of “back to the future” move, let’s look at a comparatively modern piece. This sculpture, Cybele: Goddess of Fertility, was created by Russian artist Mihail Chemiakin and installed in New York in 1993. She is made from bronze, and by far the largest of our Venuses today standing at 15 feet tall (4,57 m).

There are four faces: the front most is human, and the one to the rear looks like a lioness, which would make sense after reading about the Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük and early versions of the goddess Cybele. The animal heads to each side are horned – perhaps cows/bulls or sheep/rams. Again there are multiple breasts – eight pairs in fact. She has wide hips and impressive thighs which support no less than four pairs of buttocks.

No matter what the shape or size, the best boobs are healthy boobs. Breast Cancer Awareness month is devoted to bringing awareness of this disease to everyone. Putting this information into the public arena and making it readily accessible is important both as a means of education and as a way of fundraising. Both of these points are salient: the first allows us to up our game in terms of detection and therefore earlier treatment; the second allows us to level up research into the disease, meaning that treatments improve all the time. Early detection and state-of-the-art treatments mean higher survival rates. Simple really.

As someone who has experienced breast cancer, I cannot stress enough the importance of self-checking, and although we tend to think of breast cancer as a female disease, it can afflict men too. No matter you’re a man or a woman, cis or trans, paying attention to your boobs will always be important. Most lumps and bumps nine times out of ten turn out to be nothing at all, but not visiting your doctor when you think something is out of the ordinary is a mistake that no one should make. I went early, which is why I’m alive now and able to write articles for DailyArt Magazine!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!