Clouds in Art—Stratus, Cumulus, Cirrus, and Many More!

Clouds in art are why the term “landscape painting” is a bit deceiving. It suggests that the subject of the artwork is the land, and yet it is...

Sandra Juszczyk 25 July 2024

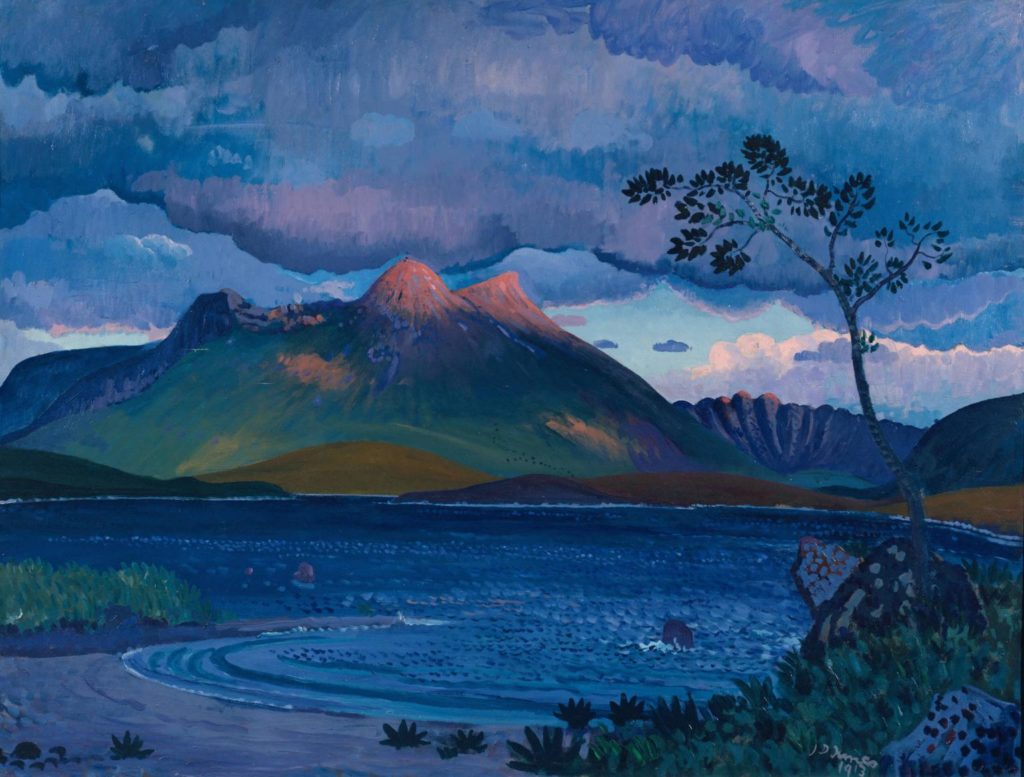

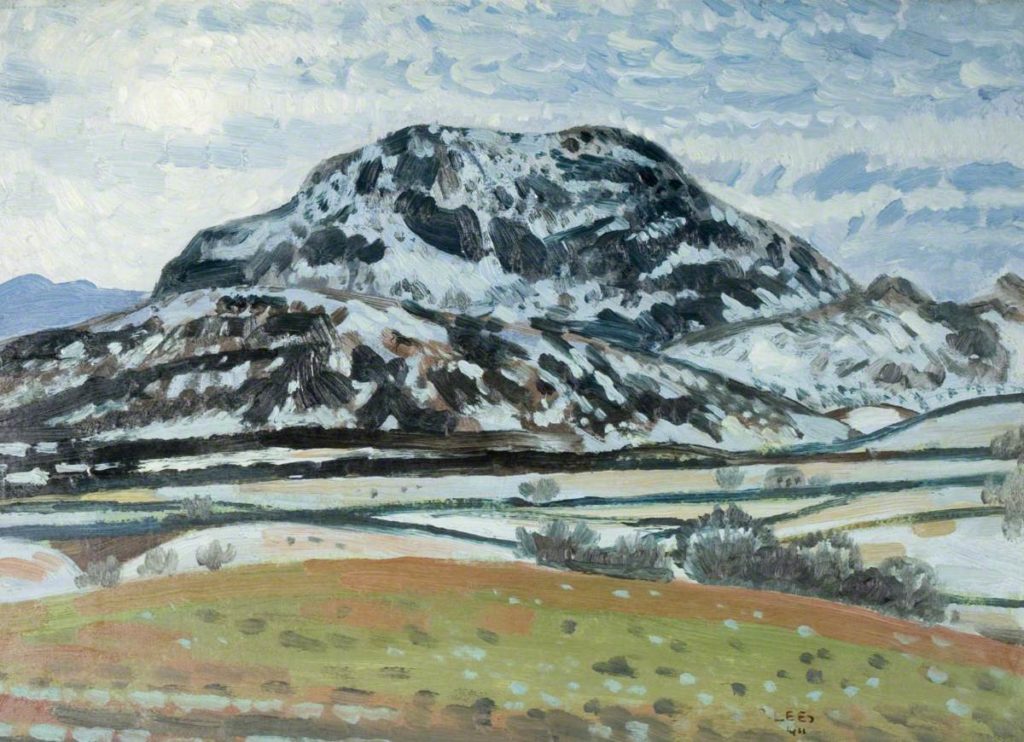

Welcome to a rollicking adventure with the Arenig School of automatic painting starring Augustus John, James Dickson Innes, and Derwent Lees. Arenig Fawr is a majestic mountain in Snowdonia in Wales. Between 1911 and 1913 three unconventional artists lived and breathed the wild landscape here, possessed by the untamed spirit of the place, producing hundreds of paintings.

Augustus John was a controversial Welsh painter, the brother of Gwen John. A wealthy celebrity, he had wives, partners, and many mistresses plus several children. James Dickson Innes was a lesser-known painter, also Welsh, and in poor health with tuberculosis, made worse by drinking, fighting, and womanizing. The third in this trio was Australian painter Derwent Lees whose wife Lyndra was a former model of Augustus John. All stays in the family.

The British public was used to rather idealized and romanticized paintings of the wilderness. The Victorian academic world set tight constraints on what was acceptable. But then along came the Post-Impressionists and the Fauvists. Artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne were storming the art world with their new styles, reacting against the naturalistic depictions of light and color favored by the Impressionists.

But at this exact same time, in North Wales, Innes was touring the landscape, sleeping in the open, and looking for something to paint. And he found it – the mountain known as Arenig Fawr. It is said that Edward Spenser based his epic 16th-century poem The Faerie Queene here. For Innes, it was love at first sight.

Augustus John and James Dickson Innes moved into a small hotel at the foot of Arenig Fawr. Later they moved into a cottage where Derwent Lees joined them and they spent two years painting by day and drinking heavily by night.

John and Innes had met at the Slade School of Art in London. They were fascinated by each other, John admired the childlike qualities of Innes, and they even became “blood brothers”. Innes felt that Arenig Fawr was sacred, his spiritual home. John called the area “some miraculous promised land”. The paintings they produced were shocking for this point in art history. The use of paint was vigorous and fresh; the use of color was fantastical. Wales had never been painted like this before and it was a sensation. The “Arenig School” was born.

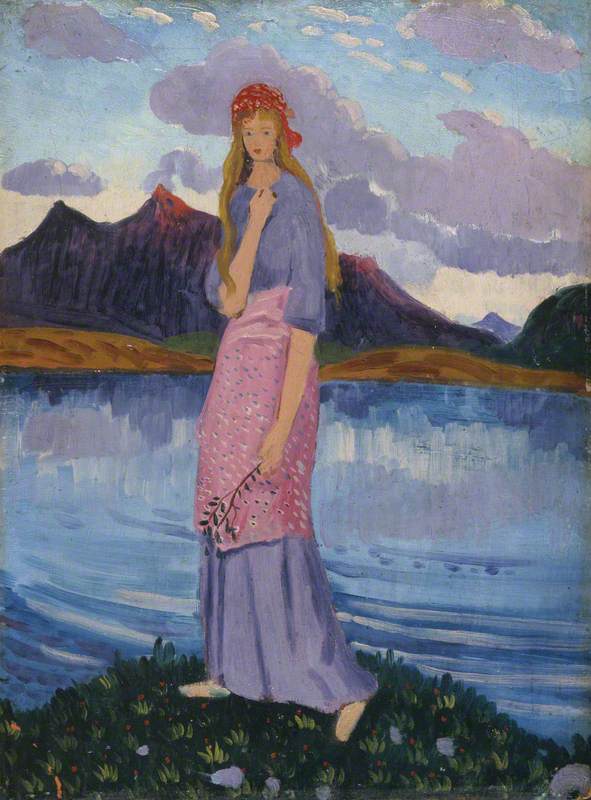

The Arenig School pioneered a style of automatic painting. The three men would roam the hills from dawn to dusk in all weathers. When inspiration struck, when the clouds cleared, or when the sunlight hit the mountain in a particular way, they would stop and paint, quickly getting oil onto the board before the scene changed. These three artists produced some of the most dramatic Impressionist landscape paintings of the 20th century. Even now, a hundred years later, people make pilgrimages to this part of remote rural Wales to pay homage.

The painters of Arenig School became involved with the Kale (Welsh Romanies). It isn’t clear how much interest they took in the true history and culture of the Kale, it seems this was more likely an escapist fantasy, where the artists dressed up and camped out in caravans. Their partying, dancing, drinking, and fighting were legendary.

Their relationships with women were complicated. John’s partner Dorelia McNeill and children visited often, but another regular was Euphemia Lamb who was involved with John and then Innes. Innes fell hopelessly and passionately in love with Euphemia. When she left, a heartbroken Innes buried her love letters in a silver casket on the top of the mountain.

Over the two years at Arenig Fawr, the artists produced hundreds of paintings. In 1913 the Exhibition of Modern Art in the USA exhibited all the European greats. Alongside them hung Augustus John, James Dickson Innes, and Derwent Lees. The show was a triumph.

Sadly a year later in 1914, Innes was dead, aged just 27. His tuberculosis and ruinous lifestyle had taken their toll. Lees was committed to an asylum in 1918 where he was detained until he died in 1931. John survived them both for many years, he died in 1961. He quickly abandoned the untamed landscapes and settled comfortably into the role of a celebrity portrait painter. The wild man became an establishment figure. Critics say that his time at Arenig Fawr was his creative high point, with Innes as his key inspiration. Those two years on the mountain, in the heart of a wild landscape, produced a magical combination of talent that can never be forgotten. Arenig Fawr was the mountain that had to be painted.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!