10 UNESCO World Heritage Sites to Visit in the Balkans

The Balkans, a region steeped in history, culture, and natural beauty, boasts a wealth of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In this article, we explore...

Nikolina Konjevod 15 July 2024

The first things that come to one’s mind when one thinks of Henri Matisse are France, Fauvism, raw shapes, and colors. But never Morocco! Why not? Actually, not so many people know that Henri Matisse visited Morocco twice.

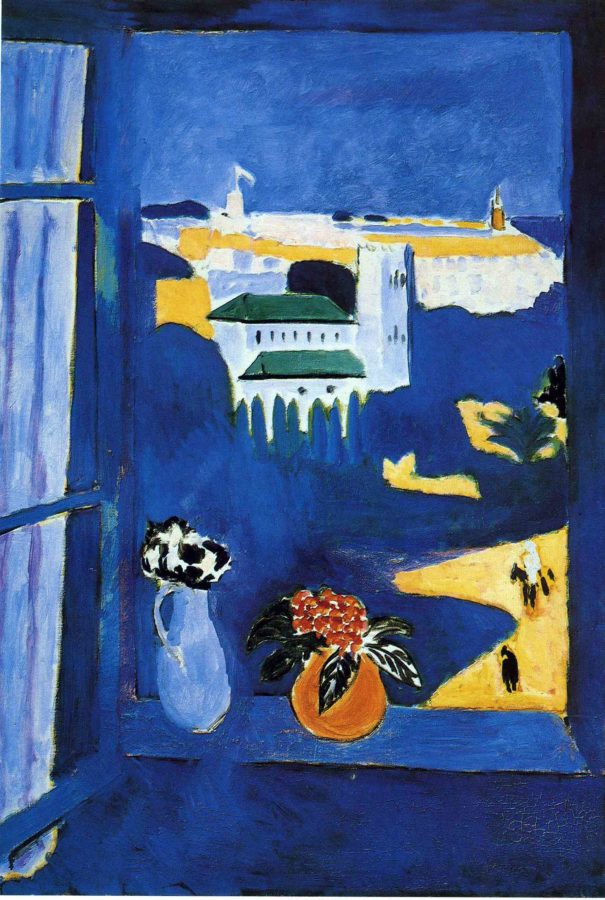

When Henri Matisse (1869–1954) first visited Morocco in the winter of 1912, he was really unlucky. The moment he was installed in the Hotel Villa de France in Tangier, a city in the north of the country, the rain began to fall. He was then obliged to postpone any outdoor activity and ended up looking through the window. The rain was pouring so heavily for days that Matisse occupied his time by painting a vase of irises in his room. He complained about the weather in a letter to the poetess Gertrude Stein. Later in his trip, the French painter would get the chance to wander around in the old city’s narrow streets, and furthermore in his 1913 second visit to Morocco.

Just as it happened to Eugène Delacroix when he went to North Africa, Matisse found Morocco so different and exotic that he ended up making numerous sketches, drawings, and paintings of it, or more precisely, of what he saw in it. For a French citizen who had never been on a trip to a Muslim country, Matisse was quite struck by the people’s physiognomy and colorful garments, the architecture, the daily outdoor scenes, and routines… And it shows in most of his works from this period (1912-1913). We can see men and women with traditional colorful outfits (jellabah, gandouras, slippers), sights from a window, cafe terraces, and much more. It was as if the exuberance and the flamboyancy in the use of colors in all life’s aspects in Morocco naturally suited the pectoral requirements of the Fauvism of Matisse.

Henri Matisse didn’t want to depict Morocco as the French orientalists did of North Africa. He did not have any interest in the fantasist scenes of nude women offering themselves to the sight of Moroccan men, scenes of grandiose salons, or traditional baths… He intended to keep a certain objectivity (even if it’s an audacious attribute to use with a fauvist) in the caption of the spirit of Morocco. And he certainly didn’t intend to paint Morocco as he was seeing it. But for me, as a Moroccan, the second I saw one of Matisse’s paintings of Morocco for the first time, without having a clue about his visit to Tangier, I immediately felt my home country’s ambiance. And after further investigation, I discovered that Henri Matisse actually visited Morocco.

As we all know, Matisse intensifies the use of color palettes in most of his works; the only difference in the paintings he made of Morocco is that the final metamorphosis of the original state of people, places, and daily life scenes and routines didn’t deviate that much from the country’s atmosphere and lifestyle. We could even dare to declare that the final work had a “Moroccan touch” to it. Even in the artist’s later canvases, we can see the influence of his two visits to the country. We can find portraits of French women with traditional Moroccan dresses and turbans. As if Matisse had some kind of nostalgia for Morocco.

Matisse gave a fresh insight into Morocco, and North Africa in general, away from the othering vision of the Orientalists with their harems and baths, which refers more to dream than to reality. Matisse went to meet the people, so close and personal. We can see that clearly through the close-up portraits of people, and the “simplicity” in the caption of people’s daily life and routines, without extravagant artifices. One feels that also in the choice of painting just one single person, instead of a whole crowd of people. It’s a sort of intimacy and objectivity in the approach of this culture, which he had never lived nor experienced before. Though you can find a couple of paintings with a crowd, they are really rare compared to the “individual” portraits.

Zorah, for instance, is an omnipresent figure in Matisse’s paintings from that period. She was somehow the artist’s favorite model from Morocco. He painted her in different places, positions, and outfits, as if he was trying to capture the essence of that mysterious woman. We are even tempted to wonder while looking at those various canvases: “Who is this Zorah?” Matisse knew a lot of people. But not all of them had the privilege to be captured in his work. So if he chose to paint Zorah, it’s because he saw something in her. Nobody will ever solve this mystery. But our consolation is the pleasure we feel in the presence of such enlightening masterpieces.

In this mise en abyme, Matisse presents us with a view of the old city of Tangier. The painting is invaded by blue, the typical color used on the surfaces of buildings in Tangier, along with white, especially in the old part of the city. So much that we are even tempted to call it Harmony in Blue… It feels as if the buildings are emerging from the sea. It’s true that we don’t see much of the city. But a closer look at the scene provides proof that it is, in fact, an Arabian country. The multiple minarets, the tiled roof, the palm tree, and especially the man riding a donkey… These are all significant clues. The two flowerpots attribute a wide depth of field to the frame. Without these pictorial elements, the painting would have seemed much flatter than it actually is. They give a certain charm to the whole scene. The horizon is perceivable only through the difference between the shades of blue (pale blue for the sky). The lines defining the window frame are so irregular that it seems as if the background scene forms one body with the foreground.

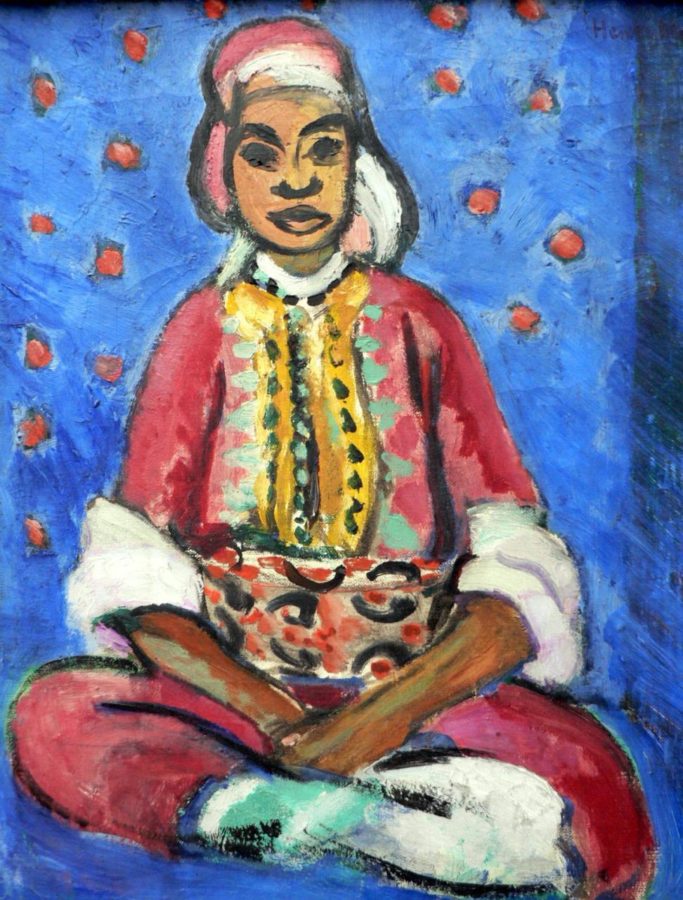

The girl depicted in this painting is placed in the corner of what seems like a room. We can vaguely see the lines that define the intersection between the two walls and the floor in the bottom right. The walls are painted in pale blue. The girl is wearing a red kaftan belted to the waist with a patterned fabric (a traditional outfit that women wear indoors in Morocco), and her hair is covered with a red veil. The garment is covered with yellow and green ornaments. The color of her dress goes along with the red dots on the wall behind her. She is in a sitting position, cross-legged and her hands joined on her lap, a typical way to sit in Morocco and in Arabian countries in general. Her sleeves are rolled up to the elbow area. Moroccan women used to do that for better mobility when doing indoor tasks and to avoid messing them up.

The paint layers are so thin that if we get closer we can distinguish the strings of the canvas. It’s as if Matisse intended to show this girl in a raw way, without entirely hiding the cloth. This feeling is emphasized in the depiction of the girl’s features and the irregular lines that define her body as if to make of all the elements of the canvas one unique body. The irregular red dots on the wall that evoke the red robe’s color act like stars, especially with that tone of blue. The meaning of the French title is lost in translation. “Mûlatresse” means a girl who is of mixed heritage.

Here is Zorah, the woman Matisse made many paintings of. She is seen (again) dressed in a pale blue kaftan, with yellow patterns. She is sitting on her legs, a position Muslims go through while praying, with her indistinct hands on her thighs. The laws of perspective are shattered in this painting. It is mostly perceivable through the disposition of the slippers vis-à-vis the whole scene. It’s as if they were added to the canvas without any consideration to the depth of field or any other fundamental law of perspective. The disposition of these slippers is as much fantasist as the presence of the bowl with the three goldfishes (a signature element in many of Matisse’s canvases). Especially on a terrace! But that’s exactly what’s fascinating about this work.

As much as it is fantasist as much as it is dreamy and beautiful. One is tempted to say: But what is the goldfish bowl doing there? It seems as if she is in a contemplative mood, isolated from reality and the outside world. In fact, no external element of the surroundings is distracting us from contemplating the “essence” of this painting: Zorah, the slippers, and the goldfish bowl. It’s like an element of the still life genre is added to this “vivid” painting. One hides the slippers and the goldfish bowl, and all the charm and beauty of the painting varnishes. This intrusion resembles the depiction by Tolstoy of the “insignificant” detail of Anna Karenina’s red handbag just a moment before her suicide (It’s not a spoiler. Everybody knows Anna Karenina’s fate!) A triangle of sun rays is seen on the top left, with a thin strip of the sky. And again, as in many of the paintings made of Morocco, shades of blue are dominant in this work.

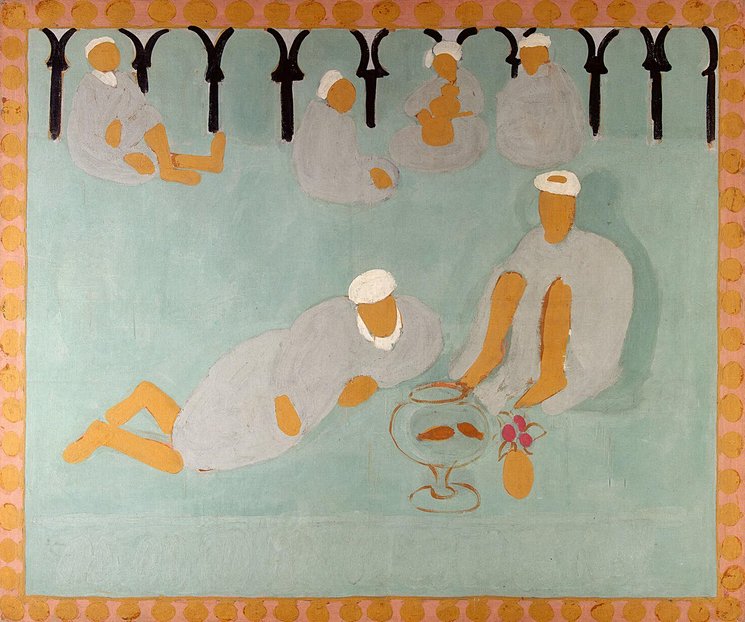

Now, this is a different painting, with different colors and tones, and with a crowd… This scene is taking place in a coffeehouse, as indicated in the title. Six men (no women, if you haven’t noticed yet!) are seen seated in different positions but dressed in the exact outfit: Grey jellabah and white turban. Aligned black arcades are seen in the back of the scene, while the painting is surrounded by a decorated strip. It makes it look like an illuminated manuscript. It’s as if Matisse wanted to add an artistic Persian touch to his work, art for which he was known to have deep admiration. This painting captures the typical idleness felt in Moroccans daily routines, which contrasts a lot with the constant haste of the European Occident. The anonymous faces and the uniformity of the outfits are meant to capture the nonchalance of Moroccan coffeehouse accustomed visitors.

Matisse’s paintings of Morocco represent a kind of eyesight on an undiscovered world which, for a Moroccan, is something they pass by daily. The daily routines imprison our perception and the unfortunate result is that we no longer give our own value to people and things we meet and experience in everyday life. Matisse’s foreign eyesight is somehow a new lens through which a Moroccan, and especially an art admirer, rediscovers the beauty and the treasures of their own country. And that’s exactly the effect of great art. It renews one’s perception, and we see people, places, and things as if we are seeing them for the first time. I somehow revisited my own country… So, for that, I would love to sincerely thank you, very dear Henri Matisse.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!