From Victim to Temptress: Salome in Art

For centuries, artists interpreted the biblical story of Salome and turned it into a lasting theme in art. But where did this fascination come from?...

Edoardo Cesarino 22 January 2026

Did you shower today, or did you make do with a quick spritz of Axe body spray? Across history, hygiene and cleanliness in art have mirrored shifting values about purity, beauty, and human nature. Our ideas around what counts as cleanliness have changed over time. From the scented Romans and their palatial bathhouses to the stinky pits of French aristocrats, our ideas of hygiene say a lot about our culture. Climate, technology, religion, and attitudes towards privacy and nudity all play a part. Intrigued? Then keep reading!

Guido Reni, The Toilet of Venus, 1620–1625, National Gallery, London, UK.

One of the most famous scenes of bathing in art history—Diana at her bath—is a theme explored repeatedly by artists. Perhaps because it is one of the most famous stories from Greek mythology? Or perhaps because we get to ogle a naked lady? In the ranking of bathing beauties, Diana, goddess of the hunt, nature, and the moon, is closely followed by Venus, goddess of love, sex, and beauty.

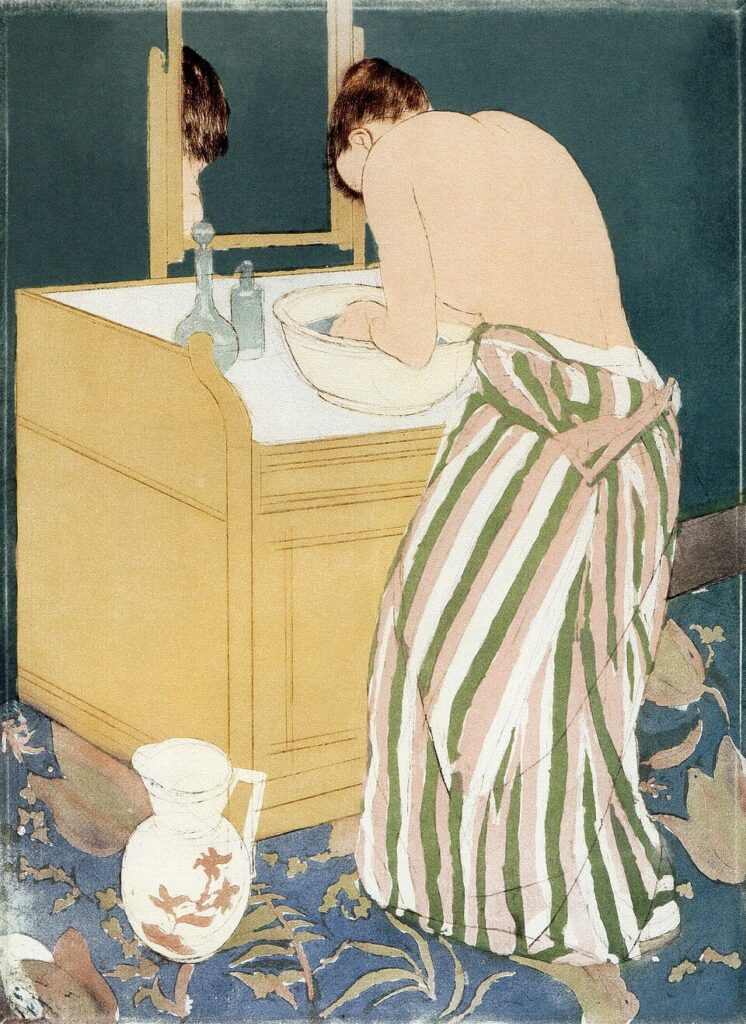

Mary Cassatt, Woman Bathing, 1890–1891, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

A woman getting ready for the day ahead is a recurrent theme in painting. In the Renaissance, we looked at goddesses, but later we started to look at ordinary women. “Ladies at their toilet” (or “La Toilette”) is a type of painting where women are seen at various stages of intimate preparation, washing their bodies, styling their hair, applying makeup, or dressing. The French Impressionists were particularly adept at these works, exploring the private home lives of women.

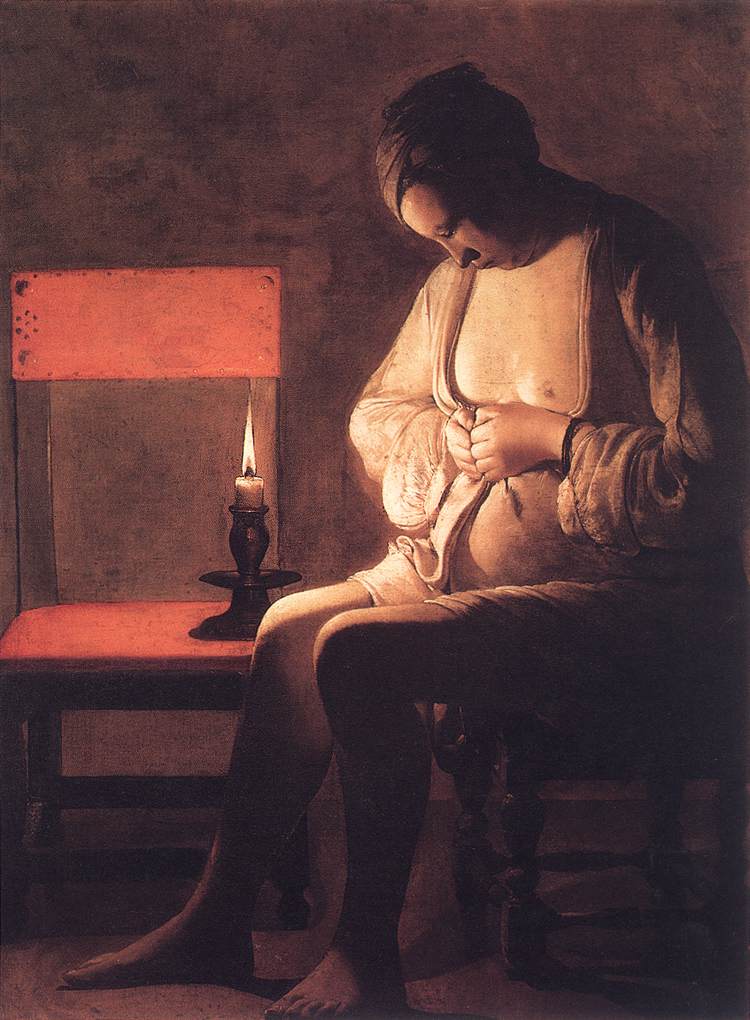

Georges de la Tour, Woman Catching Fleas, c. 1632–1935, Musée Lorrain, Nancy, France.

Bathing is not something we’ve all enjoyed throughout history. Without access to hot water, soap, and clean clothes, how could we manage cleanliness? The image above, painted in the 1630s, shows a young woman catching a flea from within her dress. A mundane and commonplace activity at this point in history—very few people had sanitation and they lived and worked in close quarters. Privileged or poor, you probably had your fair share of fleas, lice, and nits.

Pieter de Hooch, Interior with Women Beside a Linen Cupboard, 1663, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

For centuries, many people believed that dirt was actually protective and strengthening. For example, when the Plague was at its height, it was thought that blocked pores sealed the body against dangerous contagion. The rich could change their clothes, though. And an idea emerged that linen could clean the body: literally, that a clean shirt extracted dirt, and it became a point of pride to wear and regularly change high-quality smock-like shirts and chemises. Every well-to-do housewife longed for a well-stocked linen chest or linen press and, today, we still buy candles called “clean linen.”

From the perspective of many cultures, Westerners were considered a dirty bunch! While public baths in Morocco, Turkey, and Japan were visited regularly by people of all classes, the British were loath to wash anything other than their hands. The prudish West struggled to separate ideas of public bathing from sexual intimacy. And they still hadn’t mastered germ theory! But across the globe, public baths were not just about cleanliness; there was pleasure, leisure, and community in abundance.

Bathing in thermal mineral waters was practiced by our most ancient ancestors. The Minoans, Greeks, and Romans had sophisticated rituals around bathing and drinking mineral waters. The Greeks venerated water and water gods, and turned to bathing for healing and community. For the Romans, you might even say that visiting public baths became a secular religion. Pompeii—the ancient Roman city buried under a volcanic eruption in 79 CE, has some of the finest bathing-related murals in art history.

Jörg Breu the Elder, Augsburg Labors of the Months: Summer (April, May, June), 1531–1550, German Historical Museum, Berlin, Germany. Detail.

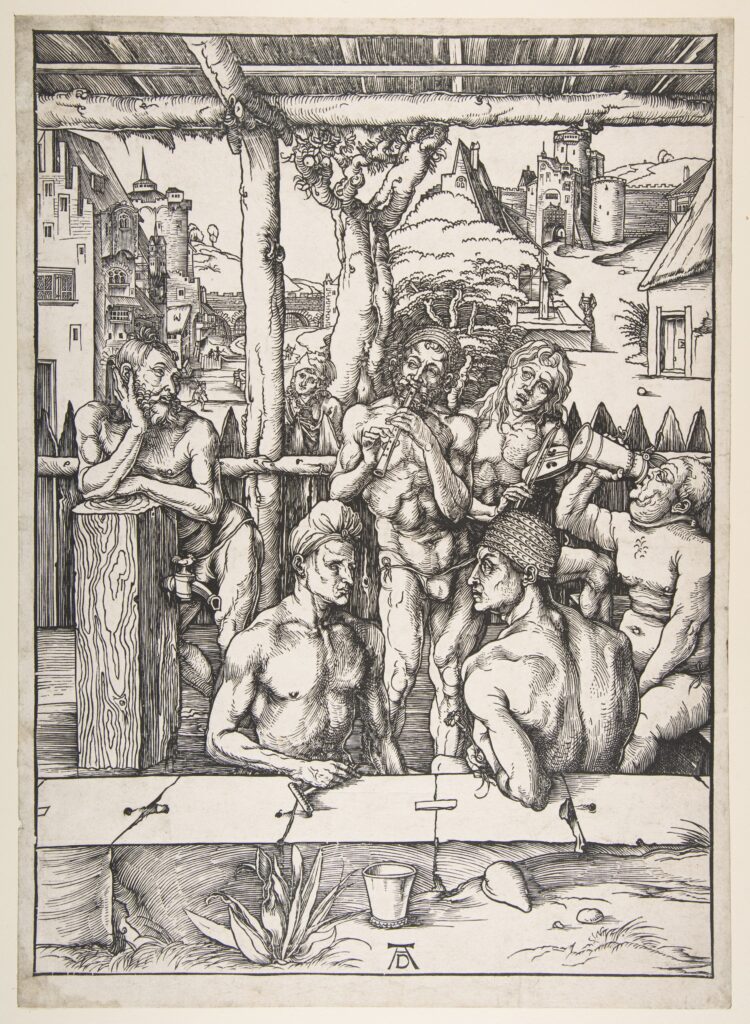

But there were times in history when Europeans dipped their toes in the water—and they certainly plunged into the pleasure side of things. Mixed, nude bathing in medieval towns and cities inevitably led to amorous and sexual encounters taking place within bath complexes, alongside gambling, eating food, and doing business. Certain establishments became known as “stew houses” as the waters were so dirty, and, more worryingly, could potentially contain typhoid and syphilis.

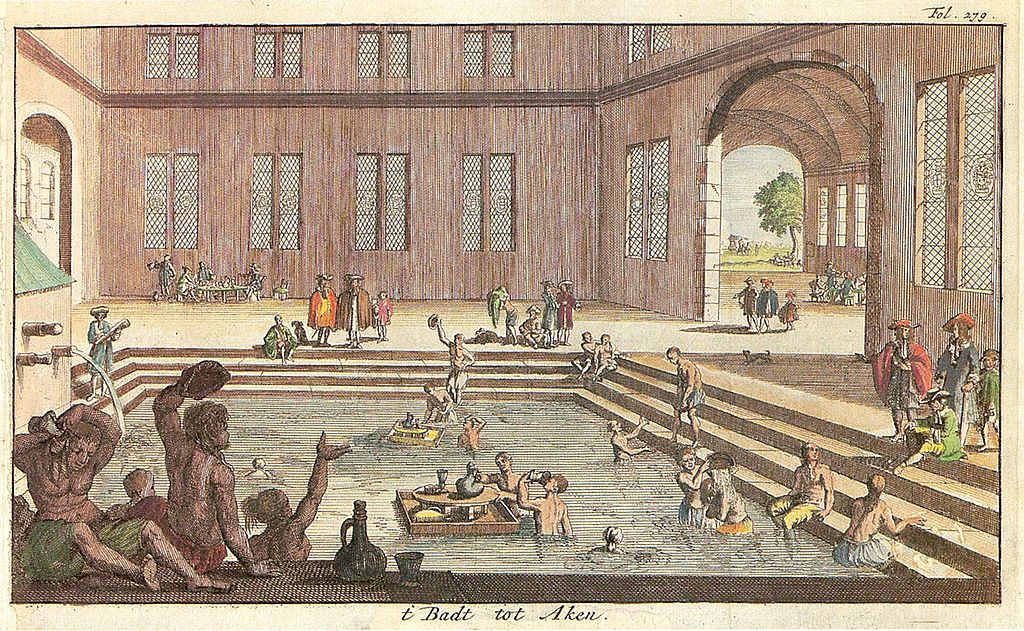

Jan Luyken, Hot Springs at Aachen, 1682. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Where money meets health and hedonism, we find beautiful and ornate architecture constructed around natural hot springs. And from the mid-18th century, there was an explosion of interest across Europe. Spas became the meeting places of the rich, the royal, and the political elite, with intrigue, love, and sexy shenanigans available alongside the curative water treatments.

Sebastiano Ricci, Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1724, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary.

Jesus Christ washed the feet of his apostles at the Last Supper. A woman believed to be Mary Magdalene washed Jesus’ feet with her tears and her hair. However, one of the most popular biblical bathers in art history is Bathsheba. Just as with Eve, religious painters could easily argue that the figure must be painted without clothes, so Bathsheba is an important figure in the development of the nude in medieval art. Bathsheba was taken from her husband Uriah by King David of Israel, who had spied on her at her mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath.

Albrecht Dürer, The Men’s Bath House, c. 1496–1497, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, USA.

There were early Christian monks and Saints who believed that dirty skin was a sign of moral purity. Apparently, the resulting smell was “the odor of sanctity.” But much more common was the connection made between physical cleanliness and spiritual purity. In 1791, John Wesley, an English cleric and evangelist, proclaimed that “cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness.”

John Everett Millais, Bubbles, 1886, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Wirral, UK.

We think that soap was invented by the ancient Egyptians. But it was the marriage of soap and the advertising industry in the 19th century that truly put those cleansing bars on the map. Soap ads for Pears, Wright’s Coal Tar, Palmolive, Lux, and Sunlight soaps became instantly recognizable and highly collectible. Bubbles, by John Everett Millais, was used to advertise Pears soap, and the painting is held in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, at the Lever family’s factory site.

Theodoor Rombouts, At the Tooth Puller’s, 17th century, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

As with soap, the Egyptians were also the inventors of tooth cleaning (by chewing frayed twigs, in case you’re interested). The Greeks and Romans used wooden toothpicks and gargled with salt water. Or sometimes they used the less appetizing option of crushed bones mixed into urine! In the Islamic tradition, Muhammad taught his disciples to chew miswak, twigs from a tree known for its antibacterial qualities.

Dentistry goes all the way back to 7,000 BCE, but removing rotten teeth still seems to use the same horrifying implements that are pictured in the image above. Or maybe that’s just my dentaphobia talking!

Jacob Toorenvliet, Surgeon Binding up a Woman’s Arm After Bloodletting, 1666, Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

Now let’s move on to a more bizarre cleanliness routine. Bloodletting is a 3,000-year-old practice involving the making of a small incision in the body to allow blood to flow out. It was believed to “clean” the patient’s body, the blood carrying toxins and sickness out. This ancient medicine was thought to restore health by balancing the four bodily fluids (or humors): blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Purging (vomiting) was another way of “cleansing” the humors.

Jerry Barrett, The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale Receiving the Wounded at Scutari, 1857, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

Thankfully, medicine has moved on since the days of bloodletting—although I hear leeches and maggots are back in fashion! We can look to the ladies for some of our cleverest advances in this field. Before we discovered antibiotics, women like Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale had realized that hygiene in the battlefield hospital meant significantly fewer deaths. Mocked by the male medical establishment, these pioneers introduced hand-washing, clean buildings, clean bedding, light, and ventilation to patient care.

Alyssa Monks, Up, 2010. Artist’s website.

Today, soap products, shampoos, and antiperspirants fill acres of supermarket shelves. Even our babies and dogs can be perfumed! The proverb “you have to eat a peck of dirt before you die” has never been more relevant, now that we know our bodies need exposure to some germs and bacteria to stay healthy. Yet, advertising agencies play on our fears and insecurities, telling us that to smell like a human body is the height of antisocial behavior. They tell us that we must be constantly vigilant about our stink. The idea of cleanliness in art shows that hygiene is not just physical, but also a matter of cultural symbolism. Would our ancestors be horrified or in awe of our modern bathing routines?

We are all glowing, and sparkling, and snapping, and tingling with health, by way of the toothbrush, and the razor, and the shaving cream, and the face lotion, and the deodorant, and a dozen other brightly packaged gifts of the gods.

The Nadir of Nothingness, 1928.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!