The National Museum in Warsaw is one of the most important museums in Poland. It also has an amazing collection of art – which obviously includes a collection of Polish art. As Polish art may not be the most popular worldwide, we have chosen ten highlights, ten Polish paintings from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw that you need to know. If you ever travel to Warsaw, don’t forget to visit the museum!

I have a confession to make. I was born in Warsaw and when I was growing up and studying art history in high school, the National Museum in Warsaw was my number one museum. So, I’m quite emotionally attached to it. The hours I spent there had something to do with starting DailyArt years later. But anyway, you will see for yourself that what hangs on its walls definitely deserves wider recognition – both within and outside Poland 🙂

This article is the part of the DailyArt app’s special month focussing on the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. Don’t miss the masterpieces we feature in the app which you can download for free on your iOS / Android devices. Let’s start!

1. Józef Simmler, Death of Barbara Radziwiłł

This work is a masterpiece of Polish Academic painting. It depicts a love drama featuring a noblewoman, Barbara Radziwiłł, and Sigismund II Augustus, the last king of Poland and a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty. The couple fell in love with each other but unfortunately she wasn’t a princess. As a result, in 1547, Sigismund had to marry her in secret and this sparked a scandal. Popular opinion saw the union as a misalliance and an affront to the state of Poland. Only after a long struggle with his mother and parliament did Sigismund manage to bring about Barbara’s coronation in 1550. Six months after the coronation Barbara suddenly died. Gossips said it was Sigismund’s mother, Queen Bona who poisoned poor Barbara.

Józef Simmler chose to paint the moment of the young queen’s death. The end of her life is symbolised by the censer on the floor and the closed prayer book on the chair. The only suggestion of regal splendour is the bedspread lined in ermine fur.

The painting was exhibited in 1860 to tremendous acclaim, solidifying Simmler as a leading artist of his day. Its success lay not solely in its subject but also in its artistic quality, the understated colours and the perfectly rendered details.

You can read more about this painting here.

2. Józef Chełmoński, Indian Summer

Chełmoński was a painter of the realist school. This is an early work produced shortly after the artist’s return to Warsaw from the art academy in Munich.

Chełmoński’s intention in Indian Summer was to depict the strength of the countryside and the fortitude of its people. In the centre of the composition is a country girl dressed in a typical Ukrainian costume. (Ukraine used to be part of Poland from 1569 to 1772) . She is lying stretched out in the middle of a pasture. In the background we can see a black dog sitting nearby, watching over the herd with his back to the viewer. It is the dog’s diligence that allows the girl to get swept away in her thoughts and wallow in her memories of the fleeting summer. The warm sun drenches the dry grass and the cloudless sky evokes the tranquilty of a September afternoon. The artist had been fascinated with Ukraine from childhood, visiting it on numerous occasions in search of nature untarnished by man.

The critics didn’t like the painting. Why should a peasant girl with dirty feet sprawled out in a field grace the wall of a sitting room or museum? This critical response hastened the artist’s decision to relocate to Paris, where he would live and work for the next twelve years. Chełmoński’s rural scenes of the Polish borderlands, all painted from memory, found appreciation in Paris and brought him great financial success.

3. Jan Matejko, Battle of Grunwald

This painting is the most famous painting in Poland, the number one highlight from the National Museum’s collection. It shows a scene from Polish history – the great victory of the allied Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania over the Teutonic Order in 1410. This huge painting, created in 1878, was intended to raise the spirits of the Polish people during the period when Poland was partitioned and no longer existed as an independent state. This is why it is still so deeply rooted in Polish collective memory.

The painting’s composition is super complex. When you stand in front of it (and it’s really huge – 4.26 × 9.87 m) you may feel that the whole painting is about to collapse on you. You feel as if you are at the center of the battle. Matejko said he felt like a “possessed man” while he made the painting. A French critic, viewing it in Paris in 1879, declared that it was a museum in its own right, requiring eight days of study before one could properly appreciate it.

At the same time, other critics pointed out the unrealistic depiction of the battle, and some anachronisms that were present. Others criticized the painting for being too crowded and chaotic. As I don’t like this painting much I will also show you the caricature created by another famous Polish artist from the same epoch, Stanisław Wyspiański. This sums up my feelings about it too;)

4. Aleksander Gierymski, Jewess with Oranges

During World War II, this painting was stolen by German forces and was only recovered in 2011. Since that time it has become one of the symbols of the National Museum in Warsaw.

The painting shows a Jewish shopkeeper. She has poor clothing – a cap on her head and a scarf on her shoulders. She is carrying two baskets of oranges. The background depicts the roofs of Warsaw houses. The woman’s face is serious, she looks tired and helpless. In contrast, there are oranges whose color is a reference to life, heat, and the southern climate.

Aleksander Gierymski was a representative of realism as well as an important precursor of impressionism in Poland. Like Courbet, he often represented the lives of humble people. Tragically, the last years of his life were spent in a mental hospital.

5. Henryk Siemiradzki, Christian Dirce (my favorite highlight from the National Museum in Warsaw)

This is my favorite highlight from the National Museum in Warsaw. Henryk Siemiradzki was a Polish painter based in Rome who is best remembered for his monumental academic art. He was particularly known for depictions of scenes from the ancient Greco-Roman world and the New Testament. His work is now owned by many national galleries of Europe.

Christian Dirce is Siemiradzki’s final large-scale history painting. It depicts a re-enactment of a Greek myth in which Dirce, Queen of Thebes, is put to death on the order of Emperor Nero by being tied to the horns of a bull and smashed against rocks. According to the writings of the Roman historian Suetonius, Nero decreed that during the games in the amphitheatre, a beautiful young Christian girl was to suffer the same fate.

Here, Siemiradzki shows the conclusion of that ruthless spectacle. The painting’s composition reflects the theatrical and spectacular arrangement that was typical of academic painting. Siemiradzki’s technical virtuosity and erudition are evident in the almost archaeological attention to detail. It is highly probable that the symbolism of the sacrificed beauty had a complicated medley of lofty meanings. Some that are universal, referencing the notion of Christianity enduring while others have a national meaning – a hope of Poland regaining independence, and artistic – connected with the artist’s concern about the future of art. (Yes, unfortunately a lot of Polish art – even though not visible at first sight – shows some patriotic, hidden symbolic meaning).

Siemiradzki’s works were sometimes a source of inspiration for his friend, the author Henryk Sienkiewicz, a Nobel Prize laureate and writer of the seminal and much-adapted novel Quo Vadis. This story features a similar scene played out by Ligia – a Christian girl tied to the back of an ox.

6. Olga Boznańska, In The Orangery (In the Greenhouse)

Olga Boznańska’s painting, In the Orangery (In the Greenhouse), depicts a girl standing in a greenhouse next to a wall, surrounded by lush plants and potted flowers. She seems to be looking anxiously and curiously at someone who has just entered. The direction of her gaze is towards the viewer who is looking at the painting.

This is one of the most important works from Boznańska’s Munich period. Whilst studying there, as well as later when she became independent as an artist, she often portrayed her friends. She was only 25 years old when this painting was created! Adolescence was the main subject of her art and was closely linked with the rise of the Symbolism movement in poetry. Boznańska’s painting refers to one of the most talked about collections of poems from that time, Maurice Materlinck’s Les serres chaudes.

Later in her life Boznańska lived in Paris where her art was greatly influenced by the paintings of James McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet and Wilhelm Leibl, artists who combined realism with impressionism.

7. Józef Mehoffer, Strange Garden

Strange Garden is one of the most exquisite and mysterious works in the history of Polish painting. It is an extraordinary mix of reality and colourful fiction.

Mehoffer painted this masterpiece during a family holiday, which he spent in the countryside with his wife and son. In an orchard filled with old apple trees bursting with gold-tinted fruit, a naked boy stands on blossoming foliage whilst holding long stalks of blooming hollyhocks. Next to him we see Mrs Mehoffer, reaching for an apple in an elegant sapphire-blue dress (designed by Mehoffer himself). In the background, a nanny in traditional costume extends her hand towards garlands of flowers hanging from the trees.

But, the most remarkable element of this painting is the giant dragonfly. Its wings resemble pieces of coloured glass in black lead frames. The dragonfly was often interpreted as a symbol of vanitas or as an allusion to the three stages in the development cycle of an insect. However, such hypotheses find no confirmation in the writings of the artist himself. To Mehoffer the dragonfly stood for the sun. This brings us back to the notion of an idyll in which the tall flowers held by the child and the light flooding his figure suggest fatherly pride and aspirations

You can read more about this painting here.

8. Witold Wojtkiewicz: Abduction of the King’s Daughter

Wojtkiewicz was a Polish painter, illustrator and printmaker. Although generally considered an Expressionist, some of his works are precursors of Surrealism.

When we look at this painting we may think that we are looking at an illustration of a fairy tale. But this scene is not an illustration of any known fairy tale. We see a little boy who is escaping with a princess on a wooden horse. In the background we see an old woman and an old man with crutches, who probably want to rescue the princess. The whole scene is quite disturbing and we seem to be witnessing a dreamlike drama. How does the story end? Were the boy and the girl happy together?

Wojtkiewicz was suffering from an incurable, congenital heart defect and this painting was created just before his premature death at the age of twenty-nine.

9. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy), Fantasy – A Fairy Tale

Witkiewicz, commonly known as Witkacy, was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer. He was active before World War I and during the interwar period.

After 1925 the artist ironically re-branded his portrait painting, the source of his economic sustenance, as The S.I. Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Company. The company’s motto was – “The customer must always be satisfied”. He offered several so-called ‘grades’ of portraits, from merely representational to more expressionistic. These latter were created under the influence of narcotics and were much more expensive. In fact, most of his paintings were annotated with mnemonics listing the drugs taken while painting a particular painting, even if the drug was only a cup of coffee.

Witkacy created the theory of Pure Form, the ideals of which he implemented in this painting, where form is more important than the content of the work.

After hearing the news of the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939, Witkacy committed suicide the next day by taking a drug overdose and trying to slit his wrists.

10. Tamara Łempicka, Lassitude

Yes, Tamara de Lempicka (to give her her full name), one of the most important artists of Art Deco, was Polish. In this article we just had to mention her! Łempicka’s style, was a blend of late, refined cubism and neoclassicism. She was an active participant in the artistic and social life of Paris between the wars and became famous as a result of her portraits and nudes.

She developed a very recognizable style, using luminous and brilliant colors which reflected the elegance of her models. Lempicka placed a high value on working to produce her own fortune. She famously said: “There are no miracles; there is only what you make.” She used her personal success to create a hedonistic lifestyle, one that included several intense love affairs.

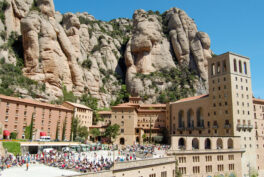

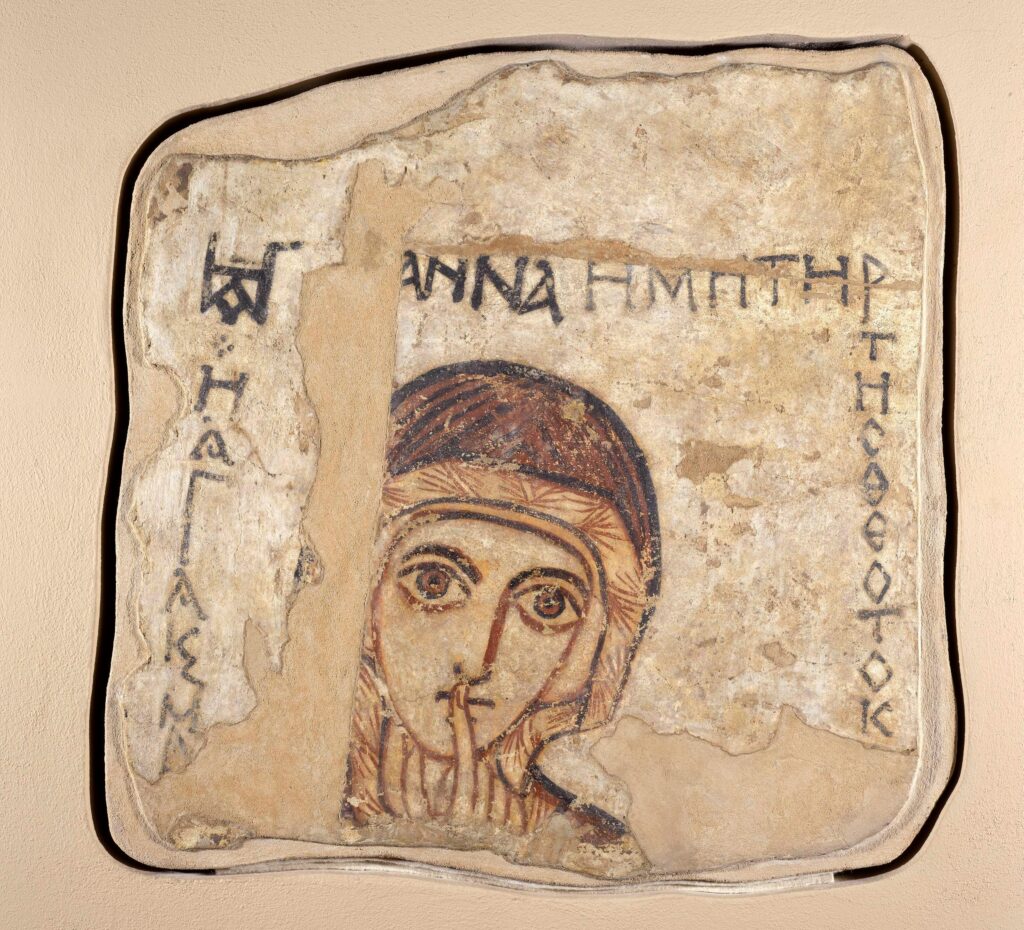

* The last, absolute highlight of the National Museum in Warsaw – Faras frescoes

Time for the last highlight of the National Museum in Warsaw. I know this is not Polish art but it is something you need to see if you ever visit the National Museum in Warsaw. This fresco is one of many Makurian wall paintings estimated to have been created between the 8th and 9th centuries. It was painted al secco with tempera on plaster and was found at the Faras Cathedral within old Nubia in present-day Sudan. The frescoes show scenes from the Old and New Testament as well as portraits of local dignitaries.

A Polish archaeological team discovered the frescoes in Faras during a 1960s campaign under the patronage of UNESCO (the Nubian Campaign). They are absolutely unique and extremely well preserved.

Preparing your travel notes? Check out other museum highlights: