Masterpiece Story: The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley’s legacy endures, etched into the contours of the Art Nouveau movement. His distinctive style, marked by grotesque imagery and...

Lisa Scalone 22 February 2024

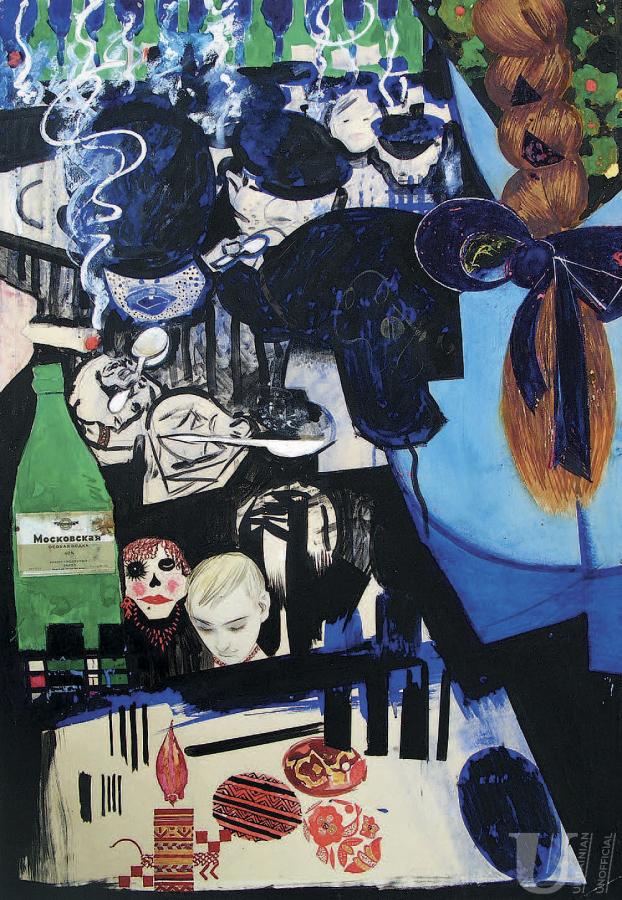

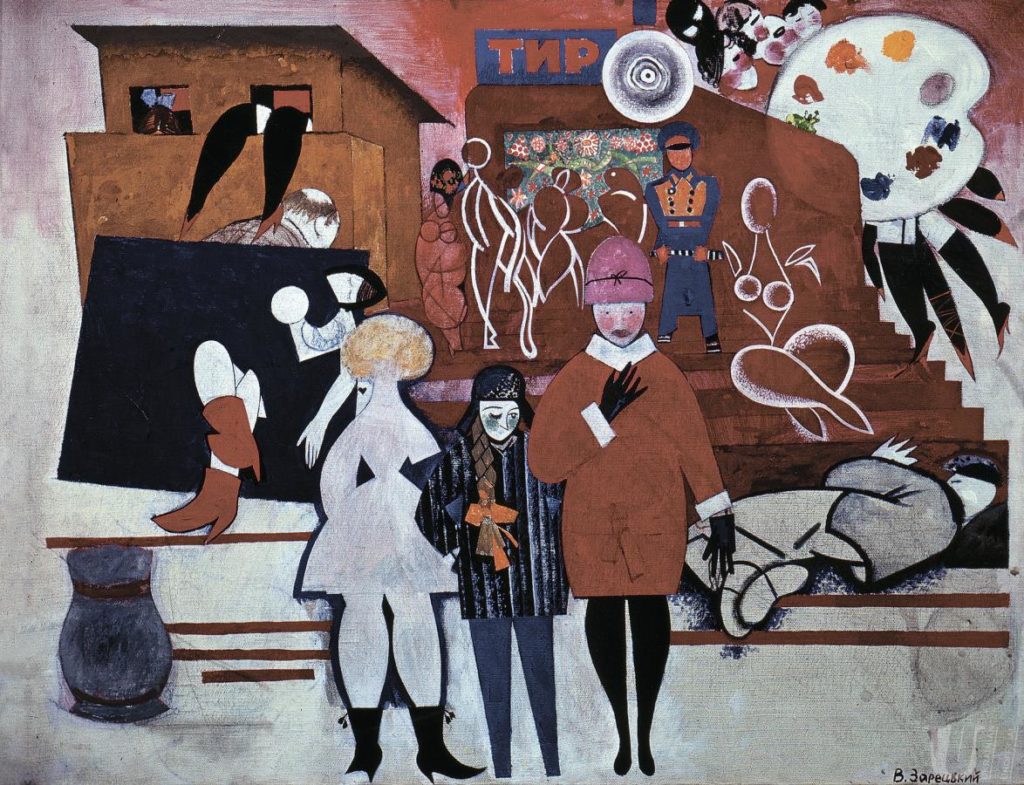

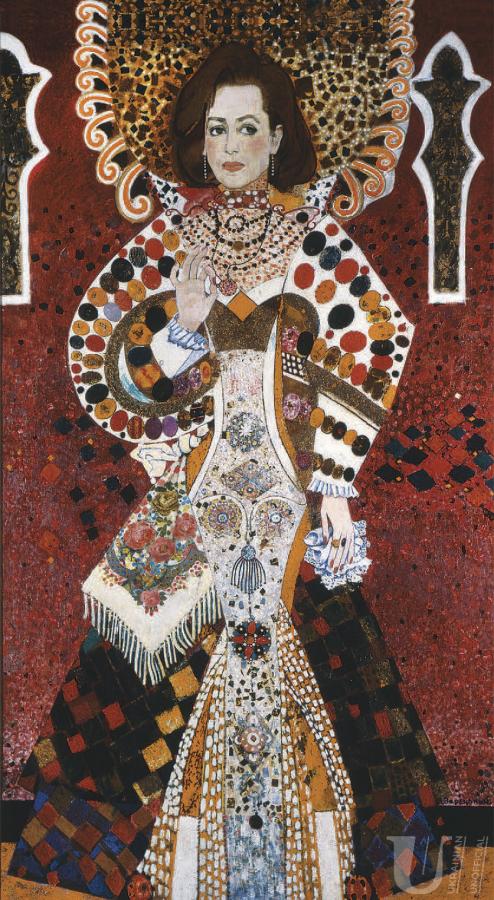

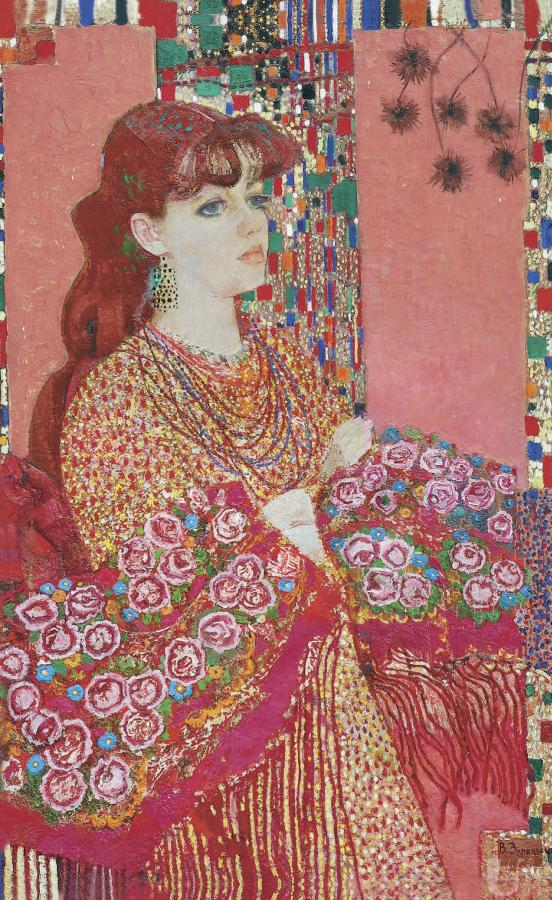

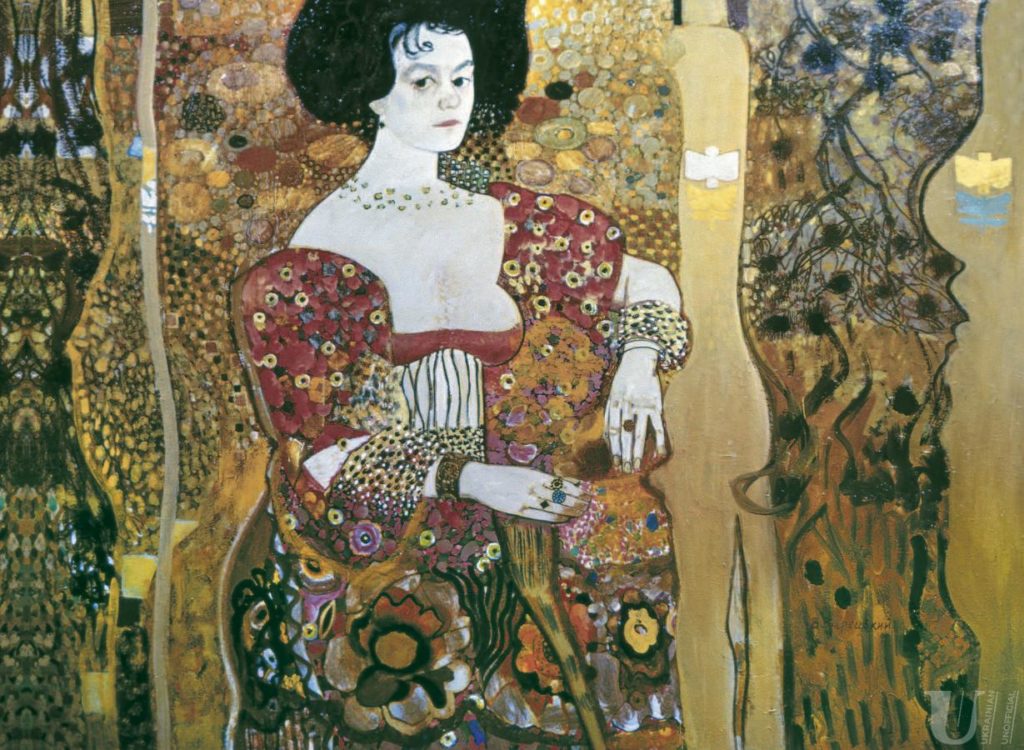

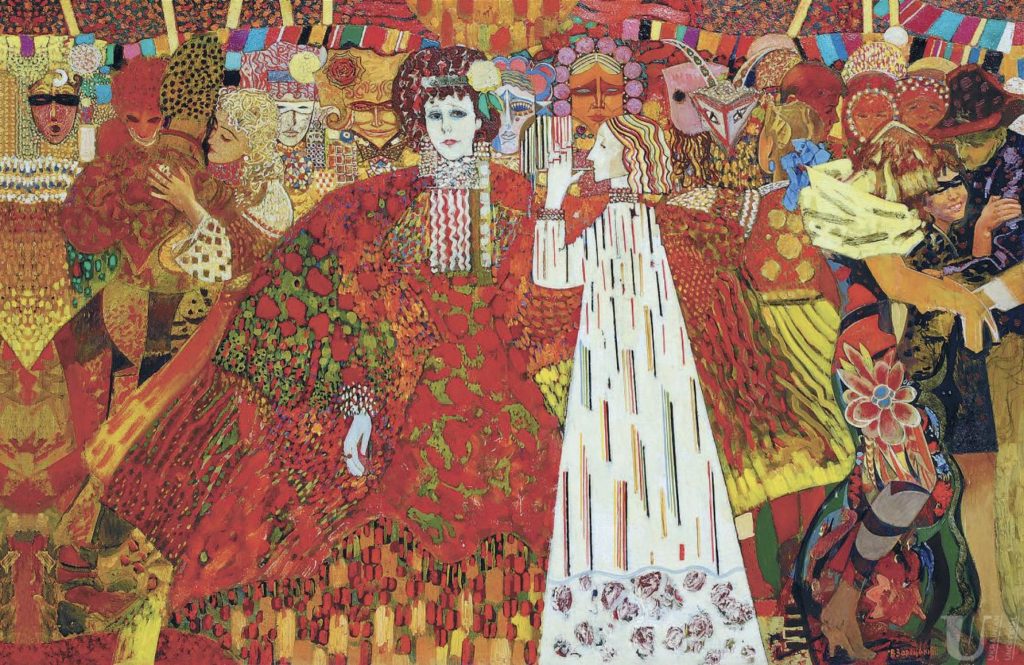

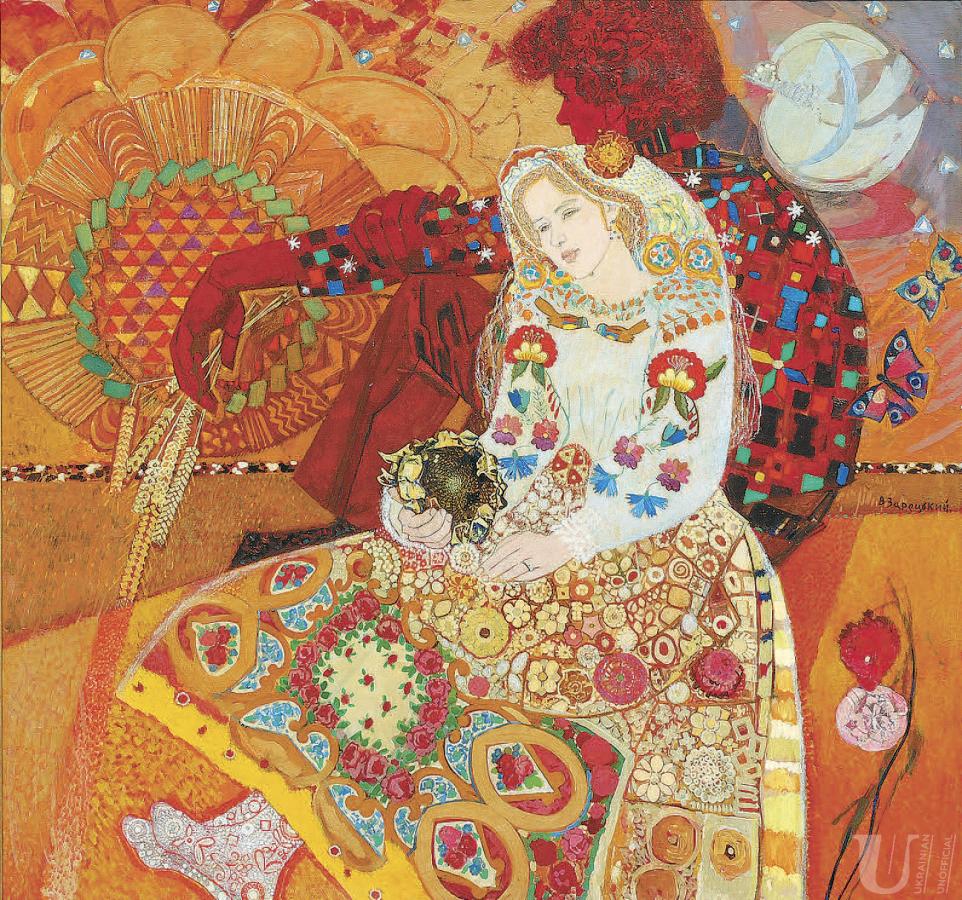

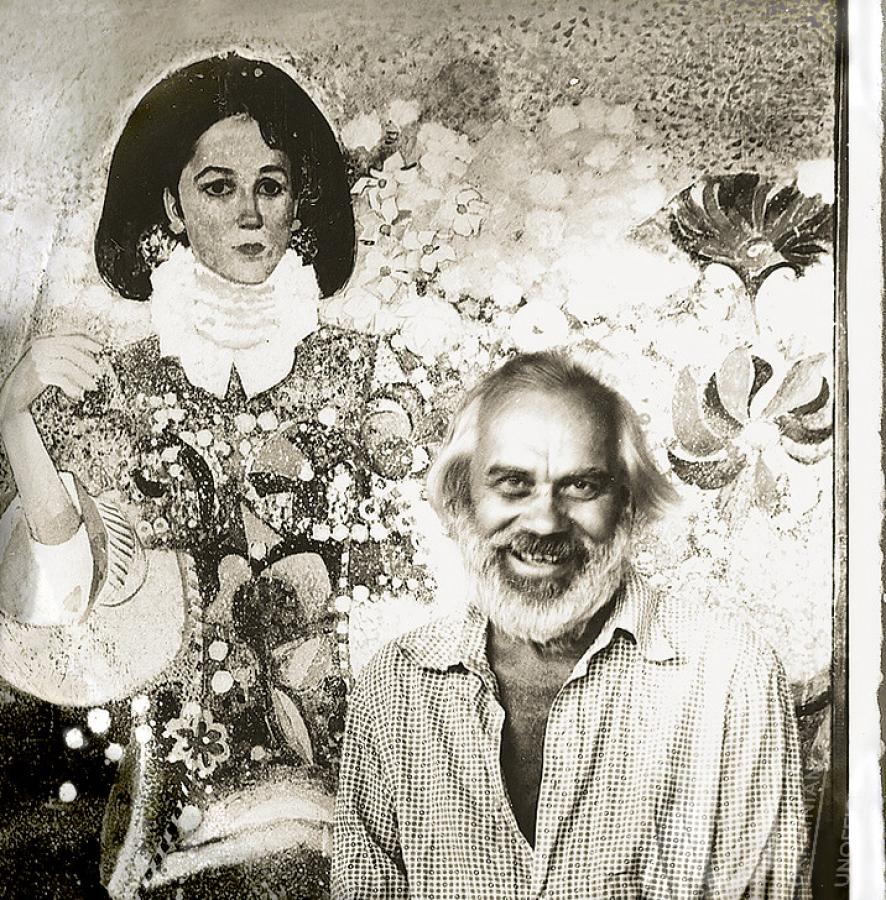

Viktor Zaretsky is often called the Ukrainian Gustav Klimt. In fact, the influence of Klimt in the artworks of this Ukrainian artist is quite obvious. This does not mean that he just copied the works of the Austrian painter; instead, he developed his own artistic language making his paintings unique.

Zaretsky was a 20th-century Ukrainian artist. As well as his wife, Alla Horska, he was one of the “Sixtiers.” This is a name given in Ukraine to the 1960s group of artists who rejected the principles of Socialist Realism with their creativity and refused to let their artworks (paintings, poems, plays, etc.) serve the interests of the Soviet authorities.

The Sixtiers were part of the dissident movement. They advocated the development of the Ukrainian language and culture as a whole. Therefore, this group of artists laid the foundations for the realization of the rights of the Ukrainian people to their own statehood. That is why the Sixtiers were often followed, summoned for questioning, arrested, and often sent to the penal colonies.

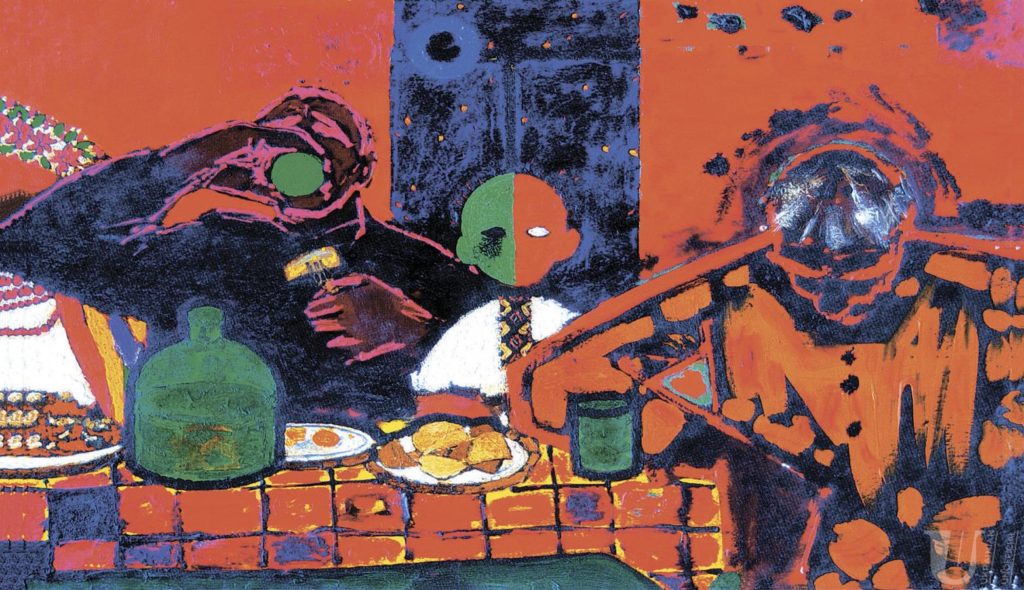

At the beginning of his career, Zaretsky addressed the themes that resonated with Socialist Realism. However, he did not paint portraits of leaders. His paintings and mosaics reflect themes that found echoes and empathy within himself. For example, the themes of peasant and miner labor.

Socialist Realism is an art movement that declared a world-view concept of a socialist society. The art conceived in this specific style was strongly influenced by the political requirements – the artists were forced to use codified forms and artistic language required by the authorities. There was very little space left for any artistic diversity, free aesthetics, or high uniqueness of the paintings or poems. Art became formulaic because it had only one function – to serve the interests of the authority.

Along with his wife, he was a member of the Creative Youth Club Contemporary in Kyiv. Zaretsky and Horska traveled to a number of Ukrainian cities and created amazing mosaics there – Prometheus, Earth, Fire, and many more.

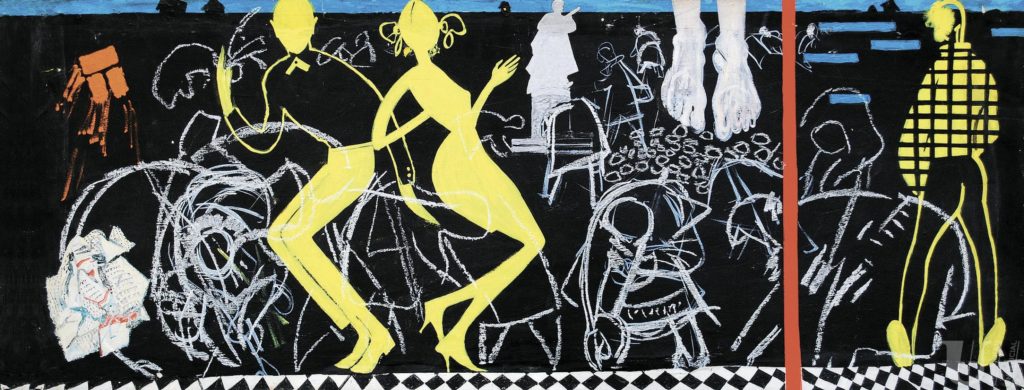

During the same period, the artist had been working on paintings in an avant-garde style. The reality was peeling off, and the so-called peasant cycle alternated with the urban one.

1970 was a tragic year for the artist. He lost both his father and wife on the same day. A full investigation was never conducted and the case was labeled as domestic violence. Allegedly, Zaretsky’s father first killed his daughter-in-law and then died by suicide by throwing himself under a train. However, there were many inconsistencies in the case that indicate that it might have been fabricated. Horska’s family and her entourage were certain that the murders were perpetrated by the KGB.

After these tragic events, depression dragged on. There were fewer social contacts and much more work in the artist’s life. It would seem that in such tough periods of life when all the senses are mixed up in a whirlpool of emotion, the canvases should have gloomier subjects and colors. Perhaps, but not in the case of Zaretsky. His Secession-style paintings, for which he was nicknamed the Ukrainian Klimt, were created in the 1970s-1980s and made him famous.

“When visiting art exhibitions in the mid-1980s, I repeatedly came across dazzlingly beautiful and reliant on unexpected artistic language landscapes, genre compositions, portraits by Viktor Zaretsky. They impressed me, awoke the imagination, and made me scared. His female portraits were especially attractive. The artist depicted his models as princesses from childhood dreams or as Egyptian queens in the paintings of the New Kingdom era, or like women in the portraits by Diego Velazquez, as well as in the mystical paintings of Pre-Raphaelites or pictures by Gustav Klimt. Their clothes and accessories were brightly decorative. They were pictured against the background of mosaic-like scattered gems or whimsical patterns of flowers and ornamental motifs. All this was absolutely atypical for the then-dominant art of socialist realism.”

–Olesya Avramenko, Ukrainian art critic.

Of course, the use of vivid colors does not mean that there was no more anger, pain, grief, anxiety, or indignation. In particular, he repeatedly portrayed his wife – in an allegorical way or not.

For the artist, reality and the hopes that didn’t come true flaked away. For some time, his life continued in his own art, where hope was still alive and anything was possible.

This is a fantasy world, alive, and bright, with unusual compositional solutions. The style is actually very similar to Klimt’s. However, Zaretsky added a lot of his own creativity. In particular, elements of Ukrainian folk and decorative-applied art are often presented.

“The refinement of composition choices, eroticism, and philosophical approach, which were the basis of the concept of the Secession style in general and the work of Klimt in particular captivated Zaretsky for some time. The close affinity of his own views and worldview with the work of Klimt was very impressive. The artist had the feeling that he had found a long lost thing, it was as if he had met a twin brother, who he was separated from in time and space. Everything seemed to be not accidental to him. Zaretsky saw Klimt not as a guru, but as a fellow fighter and colleague who came to similar conclusions and achievements in his work, only with other accents emphasized and other nuances revealed, as determined by his age and social system. Zaretsky saw in Klimt his own alter ego, found in him something that he had no chance to experience, namely freedom of creativity without ideological limitations.”

–Olesya Avramenko.

During his life, Zaretsky had only one solo exhibition. It took place in the exhibition hall of the Kyiv House of Scientists in 1989, a year before the death of the creator of the Ukrainian Neo-Secession.

Zaretsky’s works are appreciated both in the Ukrainian cultural space and outside of it. For example, in 1990, 20 paintings by the artist were sold at Christie’s auction.

In addition to museums, his paintings are stored in private collections in Ukraine, Great Britain, Switzerland, and France. The value of his artworks is also indicated by the fact that his artworks are often forged.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!