4 European Events Harmonizing Art, Nature, and Techno Music

Techno and electronic music have always shared an intimate relationship with art, intertwining rhythms, beats, and melodies with visual expressions...

Celia Leiva Otto 30 May 2024

When we think about flying objects we usually imagine birds, planes, kites, balloons, or even UFOs! It’s easy to forget that at one point the planets, stars, the sun and the moon might have been seen as flying objects too. Certainly in the medieval mind, the astronomical phenomena that are observable from our humble little planet were considered to be moving all around us as we remained static in space. We were, after all, the centre of the universe (or so we thought)!

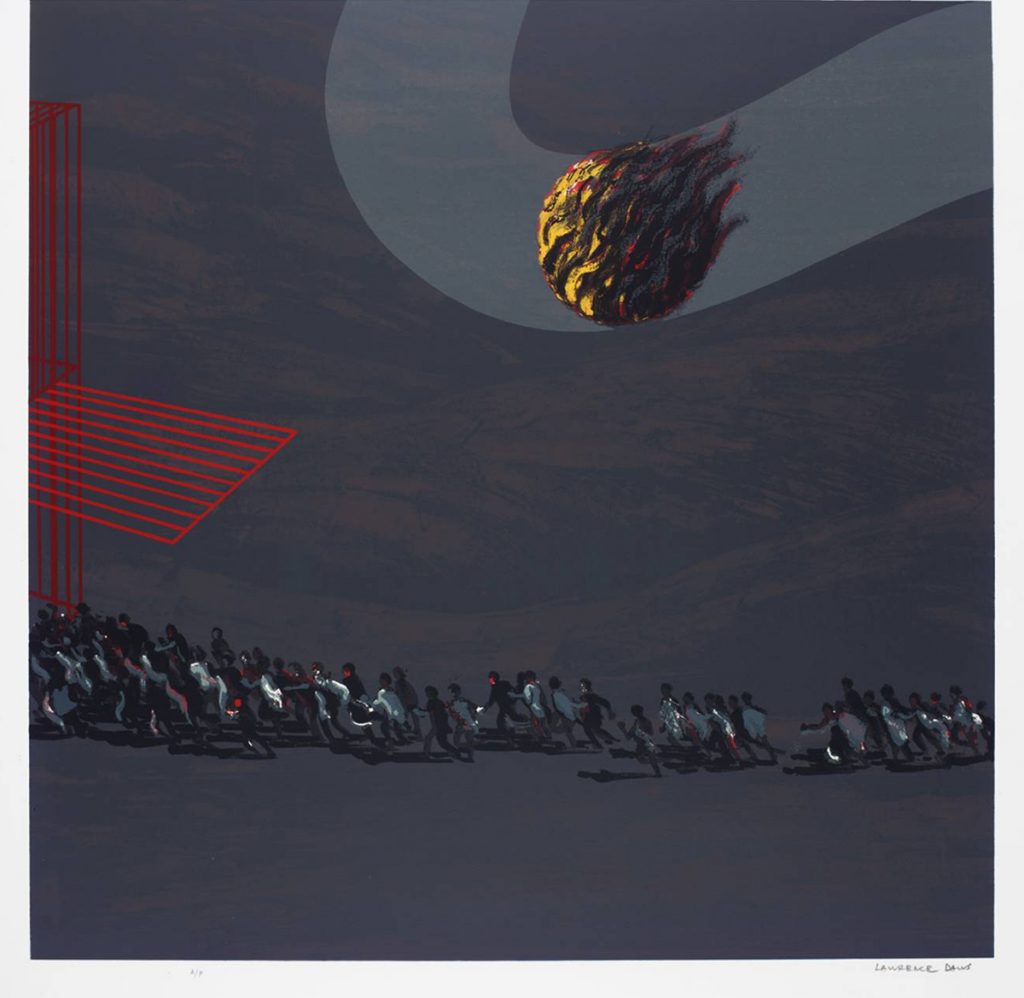

Some objects literally flew through the skies, for example the formidable meteor above, but amidst the myriad of debris hitting Earth, there were pivotal events in our astronomical history. One such event was the appearance of Halley’s Comet. This comet returns to Earth space more or less every 76 years, and can be observed twice in one lifetime by the lucky! The first known sighting of Halley’s Comet was in 239 BCE in China.

Comets were also known as “long-haired” stars and were considered to be significant in terms of divine judgement and evil omens. Halley’s Comet appears for example on the Bayeux Tapestry. Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England on the 6th January 1066, and reigned until his death at the Battle of Hastings in October of the same year. The comet historically appeared in our skies four months after his coronation, but in the tapestry it has been inserted just after Harold has taken the throne, signifying his coming downfall.

Comets were seen as symbolic of either the acquisition or loss of power (depending on your perspective). They were also seen as symbols of wealth and status, as we can see by the following portrait of Richard Goodricke.

No celestial body is more powerful, prominent or important than the sun. The sun brings light and warmth, therefore making life possible, so to be associated with this flying object is to be lauded in the same way. Elizabeth I of England is seen below with myriad suns adorning her gown. She sits in royal splendor before scenes depicting England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada, her hand laid graciously upon the Earth as both its protector and its ruler.

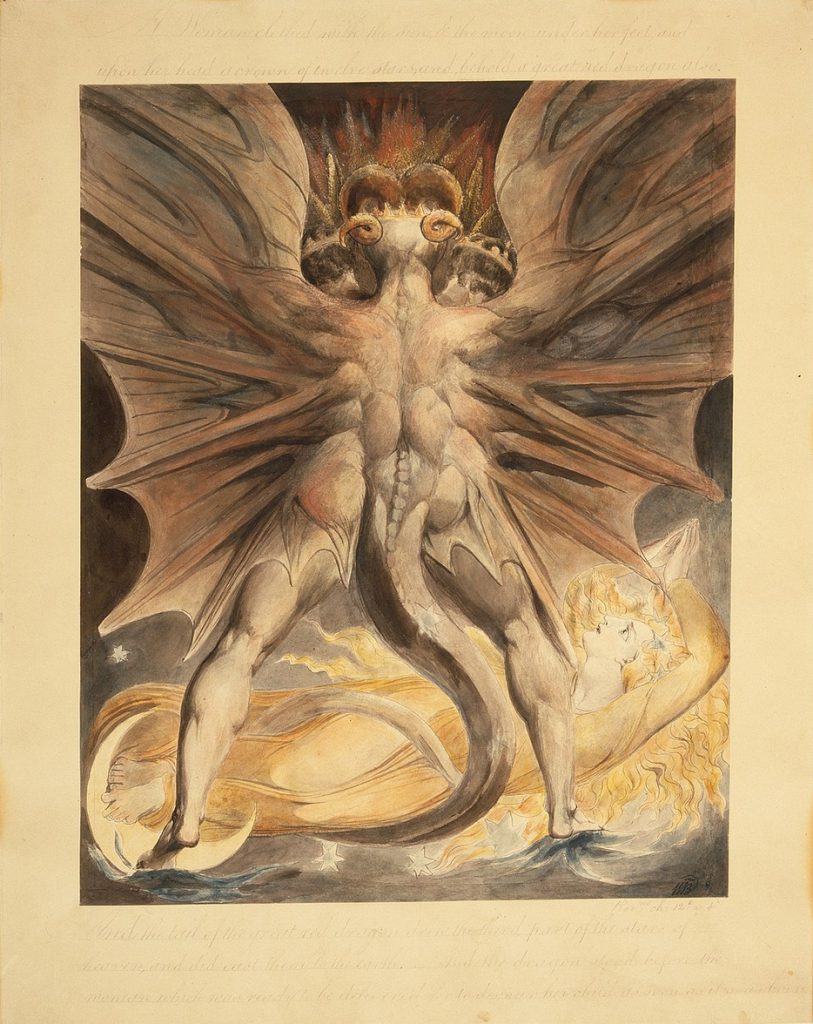

The sun can also be representative of salvation. William Blake’s famous The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun depicts Satan on the point of devouring the woman’s child (Christ) as he is born. A grim notion! Nevertheless, there she lies helpless and in labour, awaiting a terrible fate. Satan’s shadow however is not all-pervasive: the sun, or the light of God, surrounds and protects the woman, her eyes uplifted towards heaven and salvation. Despite his formidable presence it is clear that Satan is not the one with power.

We now move away from the fiery empowerment of the sun to the cooler, more thoughtful presence of the moon. In this painting by Caspar David Friedrich a man stands alone, his head lowered, before a stone monument. He is dressed for colder weather but leaves remain on the trees so perhaps this is, significantly, an autumnal scene. As life dies back in these months so too do our thoughts turn to the gradual passing of time, its rhythms and its lessons. The ancient stone and the man seem bonded beneath a young, waxing crescent moon. Old and new mingle together while the night sky gently shifts hour by hour and the world keeps turning.

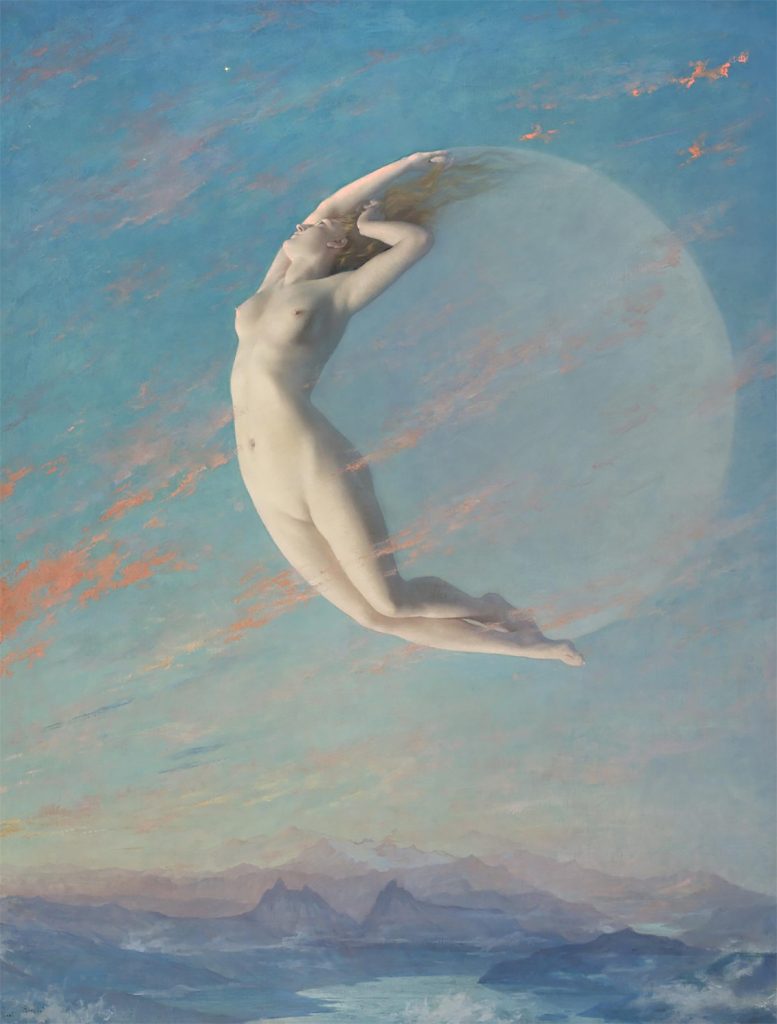

Traditionally the sun and the moon have masculine and feminine traits respectively. This was certainly true in Greek mythology. Selene was a Titan goddess, daughter of Hyperion and Theia, and sister to Helios (the sun god) and Eos (the goddess of the dawn). Selene (her Roman equivalent is Luna) drove a silver moon chariot across the sky each night. The moon is mysterious and understated, yet ominous and highly charged. Apply these qualities to a woman and the more uneasy among us will reply with words such as “unreliable” or “mercurial”, yet the moon has a firm path of growth and decline that never fails. In these phases can be perceived the many complex characteristics that allude to the feminine.

What about stars? The most talked-about star at this time of year is of course the Star of Bethlehem. While the jury doesn’t seem to be out on this subject (rather there doesn’t seem to be an obvious science-based explanation) it is more or less agreed that it wasn’t a constellation, a comet, a nova, or a supernova. Star of Bethlehem hunters are still looking at possible and unusual planetary conjunctions to explain it. That said, within the Christian narrative, perhaps the explanation is far more entrenched in divine metaphysics than anything else. Edward Burne-Jones, an associate of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, painted the Star of Bethlehem held in the hands of an angel.

Sometimes it’s permissible to simply bathe in the wonderment of observable space! We look up at the sky, day or night, and see an array of beautiful objects ranging from clouds and the sun to planets and stars. What’s not to love? Van Gogh was inspired to create The Starry Night whilst recuperating in an asylum having amputated his own ear. It is a reminder that even out of the most abject pain beauty can still emerge.

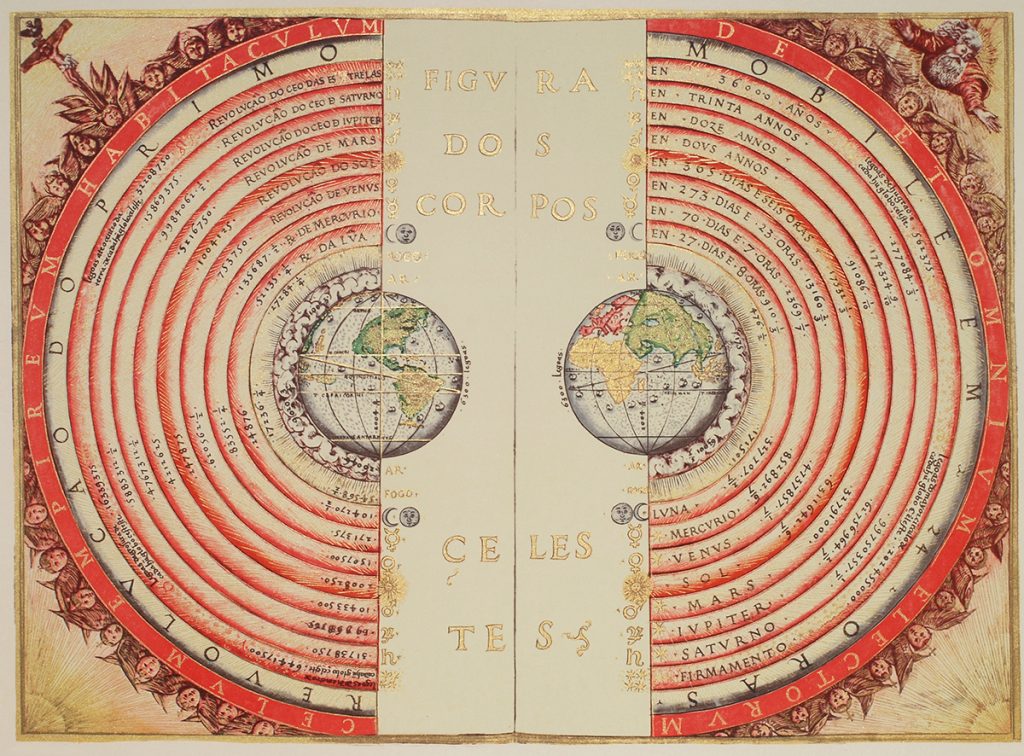

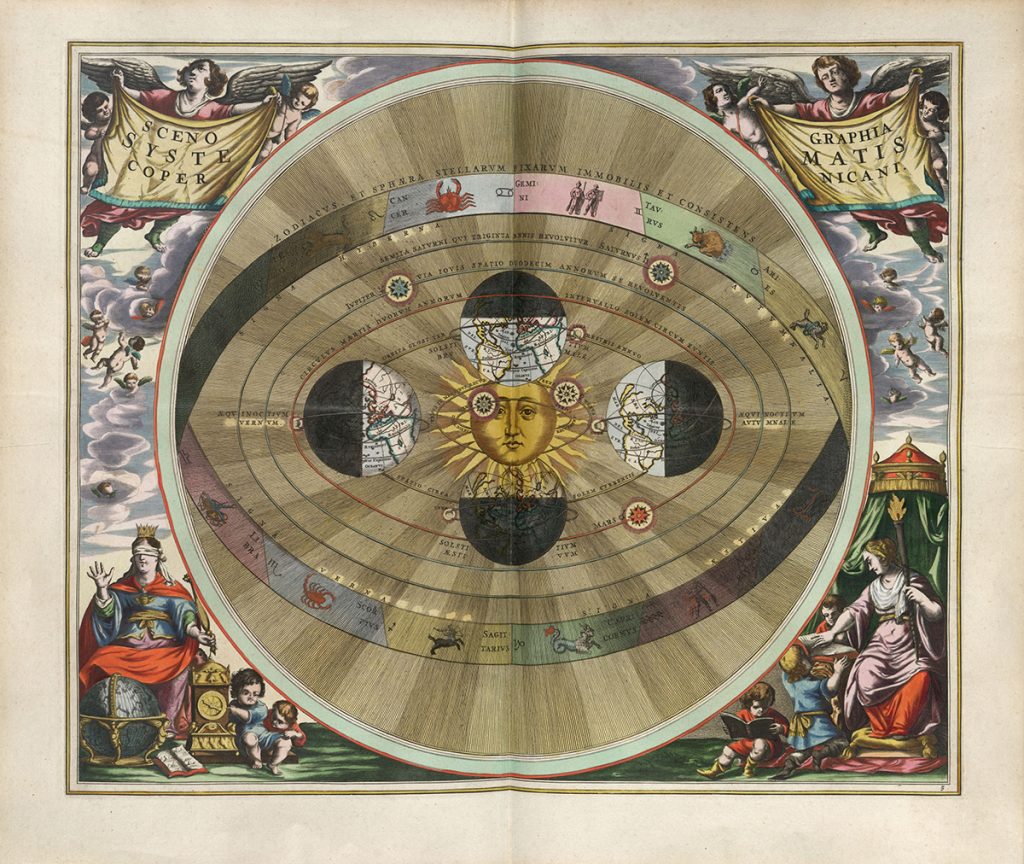

The first records of our skies are found in cave paintings dating back 30,000 years. Since then the night sky has been observed, interpreted, tracked and recorded, and by the time of the Renaissance era interest in this subject had not waned. Whether or not the Earth was at the centre of an identifiable system was highly contentious: the Church believed that it had to be, because God placed Man at the centre of all creation.

Others believed that in fact the sun was at the centre. This idea was not new: as early as the 5th century BCE Greek philosophers were postulating a heliocentric model for our small part of the universe. It was the astronomer and mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus (Mikołaj Kopernik), who put forward a more definitive version of this theory. In his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium he put forward a working hypothesis that described what we now recognize as our Solar System. It was by no means perfect, but despite this (and despite it subsequently being banned by the Church) it became one of the pivotal scholarly events that helped to usher in the Scientific Revolution.

The planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were all identified as early as 1000 BCE. Uranus followed in 1781, and then Neptune was discovered in 1846. All except Earth have been named after Greek and Roman deities.

Just for fun, let’s revisit a film that was released a few years ago to get some perspective on just how enthralling and incredible these objects really are!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!