4 European Events Harmonizing Art, Nature, and Techno Music

Techno and electronic music have always shared an intimate relationship with art, intertwining rhythms, beats, and melodies with visual expressions...

Celia Leiva Otto 30 May 2024

So far we’ve had balloons and celestial bodies as part of this series. Now we move to kites as our flying objects in art, but where do we start? There are so many examples! Probably best, therefore, to start at the beginning.

Kite flying is in fact thousands of years old and hasn’t always been associated with carefree summer days and colorful kite festivals. The first documented reports of kite flying are from Ancient China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), where they were used in a military capacity, for example, to aid the calculation of distance between one point and another. They were also used to deliver important messages, and sometimes (in a non-military capacity) to deliver romantic ones! The activity of kite flying was slowly disseminated via trade routes to other countries.

By the 7th century, kites had arrived in Japan. Here they were initially used by Buddhist monks to ward off evil spirits or to bring good fortune, but it wasn’t until some considerable time later – during the Edo Period (1603–1868) – that kite flying became accessible to the lower classes (those below Samurai). After that, it quickly became a national pastime.

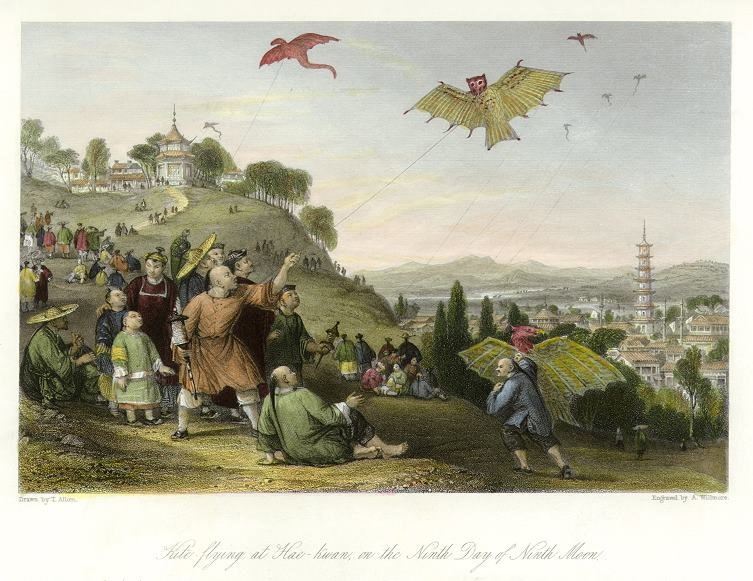

The use of kites for both practical and playful reasons spread out through Asia, eventually arriving in Medieval Europe. The image above depicts a rider using a dragon kite as a means to terrify the enemy. This and other interesting technologies of warfare can be found in Konrad Kyeser’s Bellifortis, which is an illustrated manual of military technology. In China, flying kites continued to be used for measuring distance, sending signals, and even carrying men, but also for fun. They were also used for kite fishing in Malaysia and kite fighting in India!

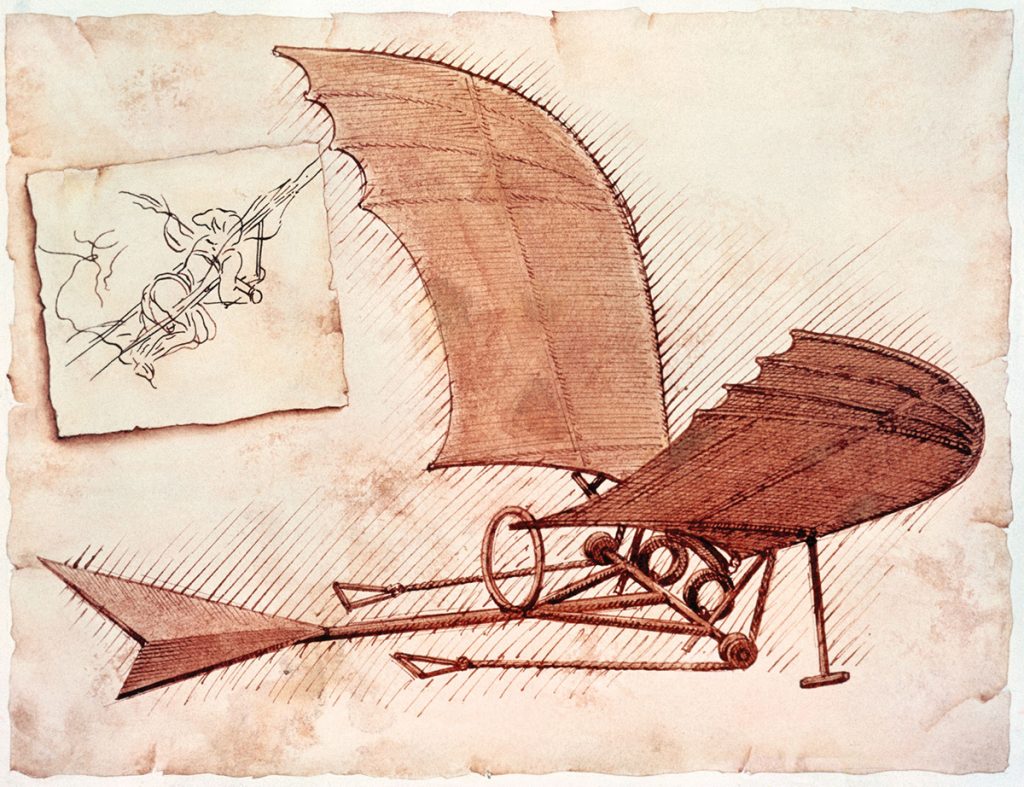

Leonardo da Vinci was famous first and foremost as an artist, but he was also an inventor. Above is an image of what is essentially a hang glider. Like a kite, a hang glider relies on the careful reading of air currents and thermal updraughts in order to remain in the air (especially important if you happen to be in one at the time). Was Da Vinci inspired by the kites of his time?

Flying kites provide endless fascination for children and adults alike. In the painting above by Netherlandish painter Justus de Gelder (1650–c. 1707) a group of boys are having maximum fun with their kites.

Kites, as we have seen, were already being used from very early on in a scientific capacity, but what about capacitors? Of course, we all know that a capacitor stores electrical energy, and kites may have had a hand in helping to discover this. Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was a pioneer in this field, credited with inventing the first ‘electrical battery’ in 1748. His experiments with all things electrical were wide-ranging: above we see a Romantic painting of him flying a kite instead of using a lightning rod, c.1752, in order to prove that lightning is electrical.

Above is an image of another group of people having fun flying kites, this time La Cometa by Francisco Goya (1746–1828). It seems a very light-hearted subject for Goya, but perhaps this is because it is a tapestry cartoon (a painting designed to be woven) and is one of sixty-three such cartoons produced as commissions for two consecutive Kings of Spain (Charles III and Charles IV) between 1775 and 1791.

Next, the unlikely spectacle of a bull fighting with a kite. The kite above should be on the losing side, but it has done such a good job of entangling the bull that the poor animal appears to have sat down, glowering in defeat. The kite wins!

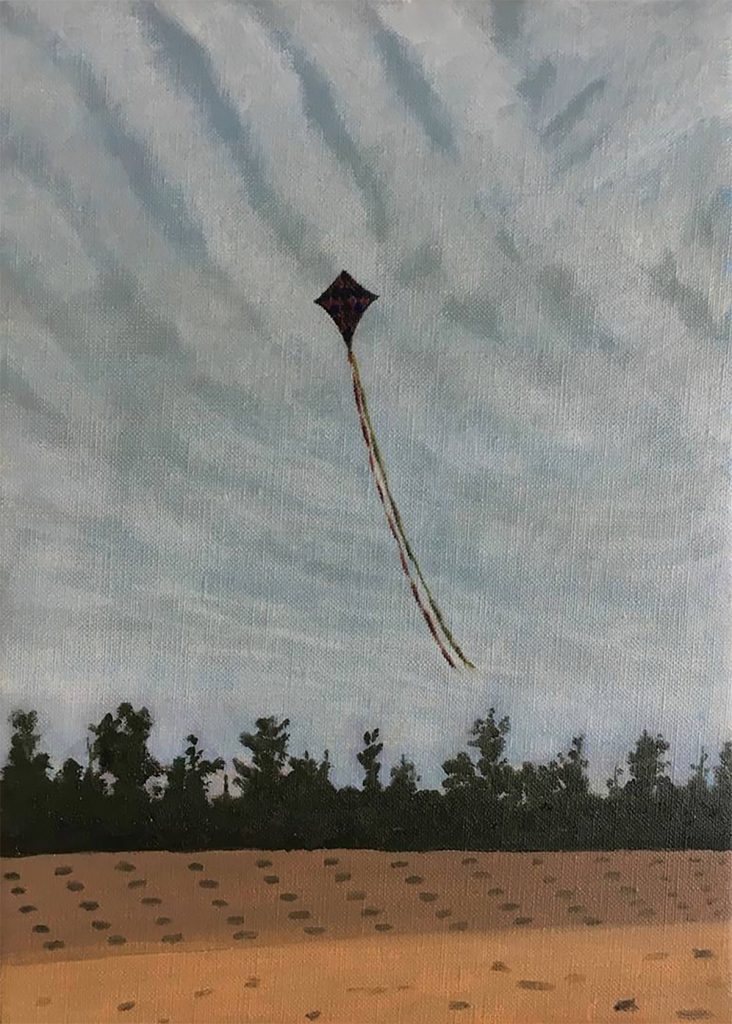

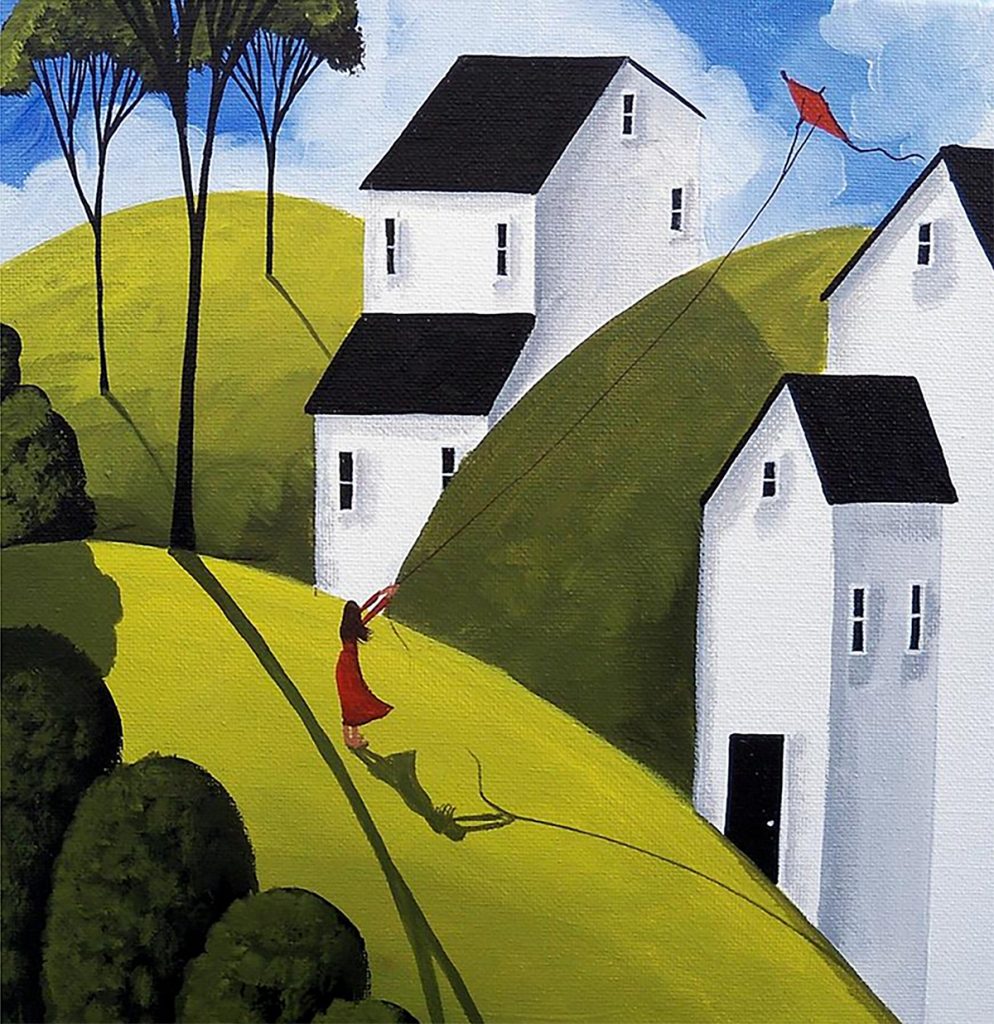

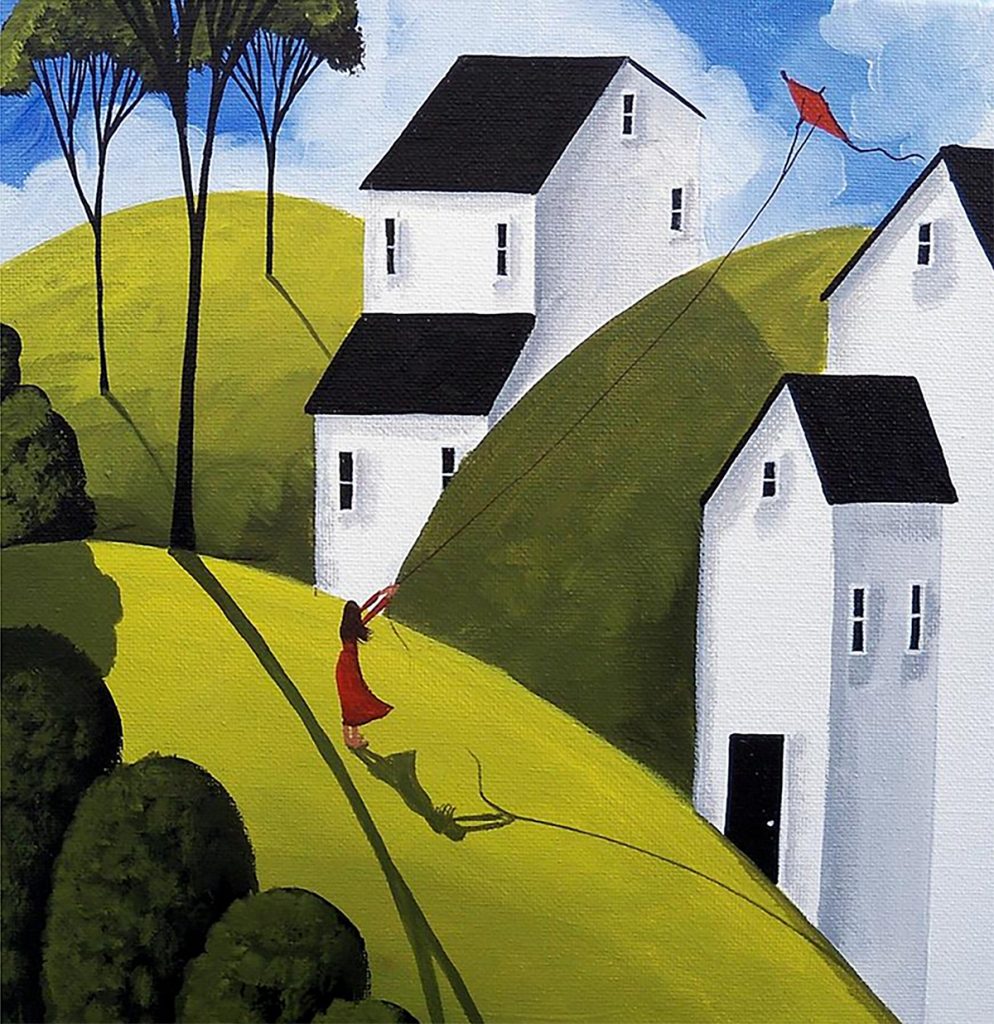

This is a good kite painting to end on. The long shadows make it feel like early evening in the summer: long hot days; the gradual onset of night. The girl flying the kite is barefoot, cooling her feet in the grass as her dress blows gently forward in the breeze. The red of the dress and the red of the kite draw attention to the joy of flying, and in such an idyllic setting. Happiness on a canvas!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!