Józef Chełmoński in 10 Paintings: Capturing the Spirit of Rural Life

Józef Chełmoński masterfully portrayed life in the Polish countryside. His paintings reveal a subtle connection between human and nature,...

Kinga Dobosz 21 August 2025

25 August 2025 min Read

From the clatter of Parisian cafés to the hushed drama of the Salon, Édouard Manet was at the epicenter of 19th-century art’s most daring upheavals. Often misunderstood in his own time, but revered by future revolutionaries, Manet famously blurred the line between old and new, academic and avant-garde. Embark on an exciting journey through Édouard Manet’s life and legacy, brought alive with 10 of his most significant and spellbinding paintings.

Édouard Manet (1832–1883) was born into a prestigious Parisian family—his father a judge and his mother from Swedish nobility. Destined, in his parents’ eyes, for a solid legal career or a naval officer’s life, Manet proved more headstrong and imaginative than they bargained for. After failing the naval entrance exam twice, he resolved to become an artist, studying under the rigorous tutelage of Thomas Couture. But Manet’s real education came from the halls of the Louvre, where he copied masterpieces and honed a keen eye for light, color, and composition.

A born observer and, by many accounts, a charismatic bon vivant, Manet mingled with writers, poets, radicals, and the rising stars of the Impressionist movement. His friendships with Charles Baudelaire, Émile Zola, and later with Claude Monet and Berthe Morisot, enriched his art and kindled his rebellious spirit. Throughout his career, Manet remained both an insider (courted by café society and the literary elite) and an outsider (snubbed by the academic establishment), forging a path that was equal parts controversy and triumph.

Édouard Manet, The Spanish Singer, 1860, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA, Museum’s website.

When this eye-catching painting premiered at the 1861 Paris Salon, critics hardly knew what to make of it. Manet—buoyed by his passion for Spanish music, culture, and the work of painters like Velázquez—presented a Paris street musician in vibrant color and energetic, visible brushwork. The bold technique shocked many, with some critics praising its unconventional power, while others found it unfinished. The painting announced Manet as a daring new talent ready to challenge tradition.

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries Gardens, 1862, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, Ireland.

While most artists painted serene landscapes or heroic figures, Manet dived into the everyday buzz of contemporary Paris. Set in one of the city’s grandest parks, this painting bursts with recognizable faces, including poet Charles Baudelaire and Manet himself. It brims with the music, laughter, and flirtations of Second Empire high society, capturing the fleeting, modern energy that defined Manet’s Paris. Viewers were left to wonder: Is this chaos or poetry? Manet insisted it was both.

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe), 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Few paintings in history have triggered such a turbulent reaction. A scandalous picnic featuring a nude woman calmly socializing with clothed men was, for 1860s Paris, positively explosive. Drawing inspiration from Renaissance group scenes yet thrusting them into the present day, Manet dared viewers to question their own assumptions about propriety and art. Rejected by the official Salon, the painting’s exhibition at the Salon des Refusés made Manet an overnight sensation, and a lightning rod for both praise and ridicule, famously defended by Zola and other intellectuals.

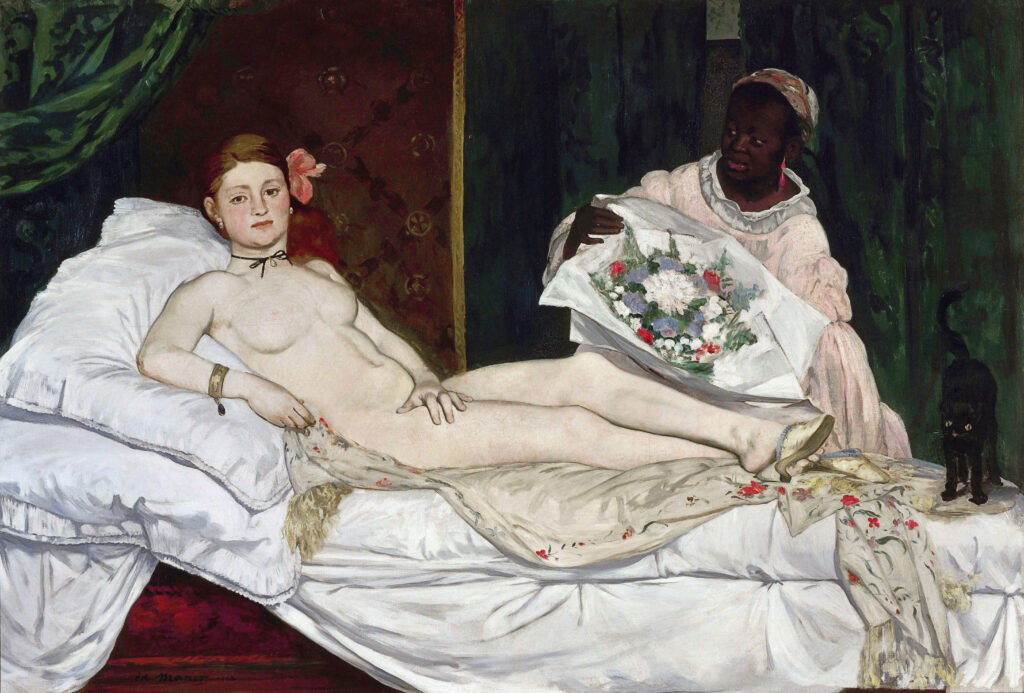

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Upon seeing Olympia, crowds gasped at the brazen simplicity of Manet’s reclining nude, her unflinching gaze, assertive composure, and clear implication that she was a Parisian courtesan, not a mythic goddess. Critics decried the painting’s sharp lines, shocking subject, and sparse shading, but modern artists immediately recognized Manet’s disruption of tradition as groundbreaking. Manet responded to the uproar with a wry grin, unwittingly helping to open the floodgates for the Impressionists who would soon follow.

Édouard Manet, The Fifer, 1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Inspired by Spanish master Velázquez, Manet painted this vibrant portrait of an anonymous military fife player with dramatic simplicity. The flat, bold patches of color stand out against the nearly featureless background, a stark contrast with academic convention. French critics, baffled by the painting’s lack of “finish,” widely rejected it; yet Manet’s fellow avant-garde artists saw the work as a revolution in capturing life directly and honestly, without the frills or flourishes of the past.

Édouard Manet, The Balcony, 1868–1869, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

On a luminous Parisian balcony, three figures sit amid splashes of crisp white and rich green, a clever nod to Goya’s Majas at the Balcony. Among the subjects is Berthe Morisot, a frequent Manet model and later one of Impressionism’s great pioneers herself. The work’s strange, somewhat melancholic mood and the emotional distance between the sitters suggest the complexities of modern life and relationships. Here, art becomes both a mirror and a mysterious curtain.

Édouard Manet, The Railway, 1873, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Modernity hisses and hums in this landmark work. A fashionable woman—Victorine Meurent, Manet’s favorite muse—and a curious child stand by the train station’s iron rails, enveloped in rising clouds of white steam. The train itself, symbolizing progress and the relentless march of industry, is hidden, leaving viewers to sense its presence only through smoke and suggestion. Manet masterfully captures a city (and an age) in flux, both exhilarating and ambiguous.

Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

By the mid-1870s, Manet was enchanted by the leisure pursuits of the emerging bourgeoisie and by the fresh visual language of Japanese prints. In Boating, he sets a stylish couple adrift on the Seine, their blue and white clothing echoing Japonisme’s crisp lines and vibrant patterns. The painting’s unusual crop and innovative perspective reveal Manet’s quest to keep his art fresh, open, and experimental—a true harbinger of Impressionist breakthroughs.

Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK.

Manet’s final painting, completed while he was gravely ill, remains one of art history’s most enigmatic masterpieces. A barmaid stands at a bustling Paris nightclub, her cool expression and mirrored reflection subtly inviting scrutiny. Look closely: the improbable angles and jumbled geometry prompt endless debate about what is “real” and what is artifice. A pyramid of oranges alludes, some say, to the temptations and costs of modern city life. The painting’s ambiguity and psychological depth keep art lovers guessing to this day.

Édouard Manet, A Sprig of Asparagus, 1880, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

This small still life has a delightful backstory. After selling a painting of asparagus to his patron Charles Ephrussi, who paid more than the agreed price, Manet sent this extra canvas of a single spear with a tongue-in-cheek note: “There was one missing from your bunch.” The painting encapsulates Manet’s lighter side—his joy in paint, his fondness for friends, and his refusal to take himself too seriously.

Manet died at just 51, but in less than two decades had upended the Parisian art world. With one eye on the past and one firmly on a rapidly changing present, he documented urban reality with wit, boldness, and compassion. Manet’s rejection by the Academy only fueled his impact; through friendships, feuds, and a steady string of sensational paintings, Manet helped unleash a wave that would crest as Impressionism and modern art. Today, his legacy is not just in museums but in every brushstroke that dares to defy convention.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!