Toxic Beauty: 3 Poisonous Painters’ Pigments

Did you know that some of the most admired painters’ pigments in art history are also among the most toxic? The pursuit of beauty has sometimes...

Celia Leiva Otto 8 December 2025

Adolf Hitler is one of history’s most notorious dictators. After coming to power as Führer of Nazi Germany, he and his followers were responsible for millions of deaths and the loss and destruction of countless priceless artworks. What is less known is that Hitler initially wanted to become a painter.

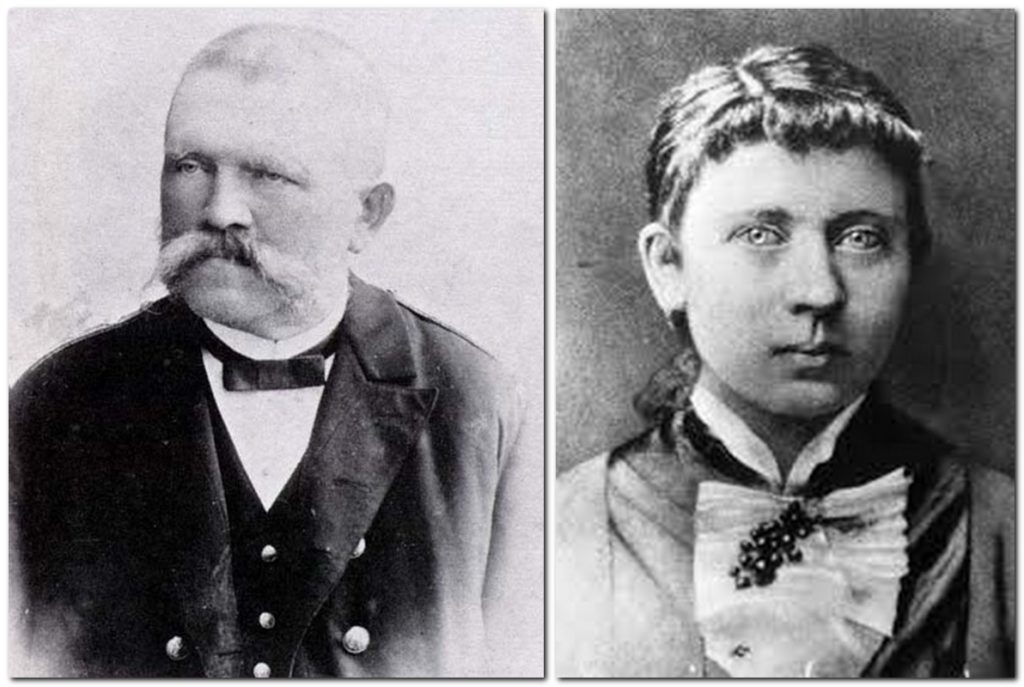

Growing up in Linz, Austria, Hitler knew he wanted to be an artist. He got support from his mother, but his father, Alois Hitler—a strict, authoritarian civil servant—strongly opposed his ambition. Alois reportedly beat his son and refused to acknowledge his artistic potentials. In an attempt to put Adolf on a more stable path, he enrolled him in a technical school.

A few years into the school, Hitler’s father died. While there was probably temptation to leave technical school in his father’s absence, Adolf Hitler completed the program with average results. He graduated in 1905 and remained in Linz to care for his ailing mother until her death in December 1907.

It was after his mother’s death that Hitler moved to Vienna, the beautiful, art-centric capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hitler saw Vienna as the ideal place to pursue his childhood dream. While his longtime friend and roommate, August Kubizek, was immediately accepted into a music conservatory, Adolf struggled to find the artistic success he had hoped for.

Hitler applied to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. He passed the initial exam, but the admissions committee found his drawing skills unsatisfactory. Naturally, Hitler wasn’t a fan of rejection and became upset at this news. In the meantime, he kept busy sketching, rubbing elbows with other artists in the city, studying, and attempting to earn a living as a worker and artist.

During the fall of 1908, Hitler re-applied to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, only to be rejected again. The professors suggested he apply to architectural school instead, as his skills seemed better suited to that field. However, Hitler was not fond of that idea; he was fixated on becoming an artist. In his autobiography, Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote that the rejection came “as a bolt from the blue.” He was so sure he would succeed.

While recent research suggests he may have received a financial loan from his family to cover his living expenses, Hitler spent much of the next year without a permanent place of residence. He moved from one inexpensive room to another and even lived in a homeless shelter for a bit.

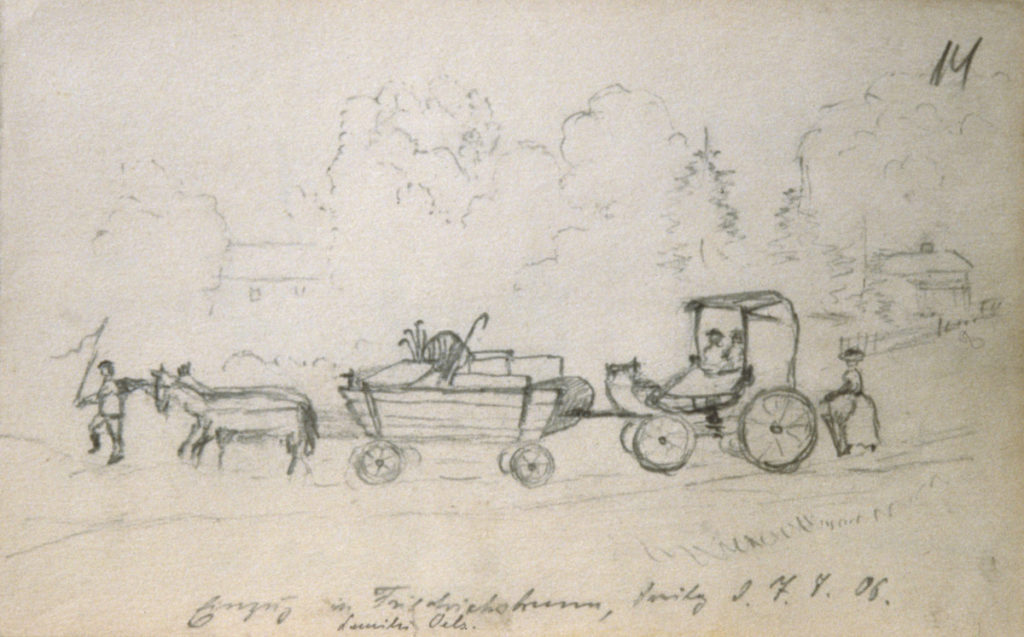

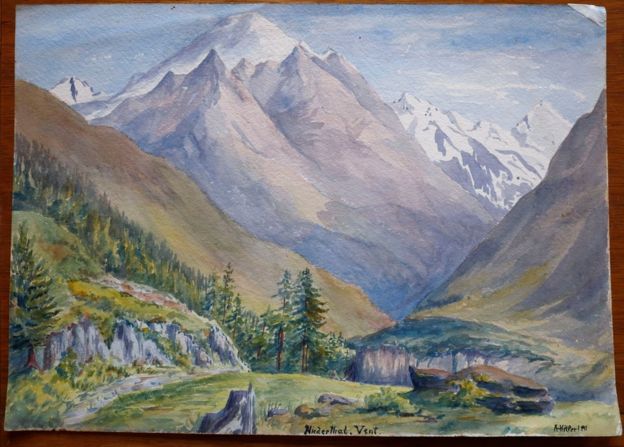

In 1909, Hitler managed to get on his feet. He had reasonable success selling his small watercolor and oil paintings depicting landmarks and cityscapes of Vienna to tourists and frame-sellers. Ironically, these were copies of postcards rather than entirely original creations. Nevertheless, the money he earned from these sales allowed him to leave the homeless shelter and move into a room in a men’s home.

While he continued to draw and paint, Hitler became increasingly frustrated with art and began to take an interest in politics. In Mein Kampf, he states that this period gave rise to his antisemitism. While his time in Vienna greatly shaped young Hitler’s world views, historians doubt this simple explanation, perhaps placing more weight on his tumultuous family life. One of the greatest contradictions of this period is his admiration for Vienna’s then-mayor and known antisemite, Karl Lueger, and the fact that Hitler’s primary patron in Vienna was Samuel Morgenstern, a Jewish store owner. Economic necessity may have influenced such relationships, as Hitler needed both income and a sense of personal success.

In May 1913, Hitler moved to Munich, where he again found some success selling his cityscapes. He even attracted a few wealthy patrons who supported him by commissioning his work. That brief stability ended in 1914, when Munich police discovered he had failed to register for military service in Linz.

But young Hitler also failed his military fitness exam. The examiners declared he was “unsuitable for combat and support duty, too weak, incapable of firing weapons.” However, in August 1914, Adolf Hitler voluntarily enlisted after World War I broke out, bringing an end to his career as a struggling young artist.

Without a doubt, the time Hitler spent in Vienna and his derailed art career contributed to the theatrical myth-making that he and his followers used to fuel his rise to power. His desire to purify the German state did not stop at exterminating Jews, Romani people, Poles, people with disabilities, people of color, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other groups. He also sought to purify the culture by rallying against modern art, calling it a “degenerate” product of the Bolsheviks and Jews. Perhaps this is only conjecture, but one could assume his own artistic tastes and shortcomings could have played a part in his views of modern art.

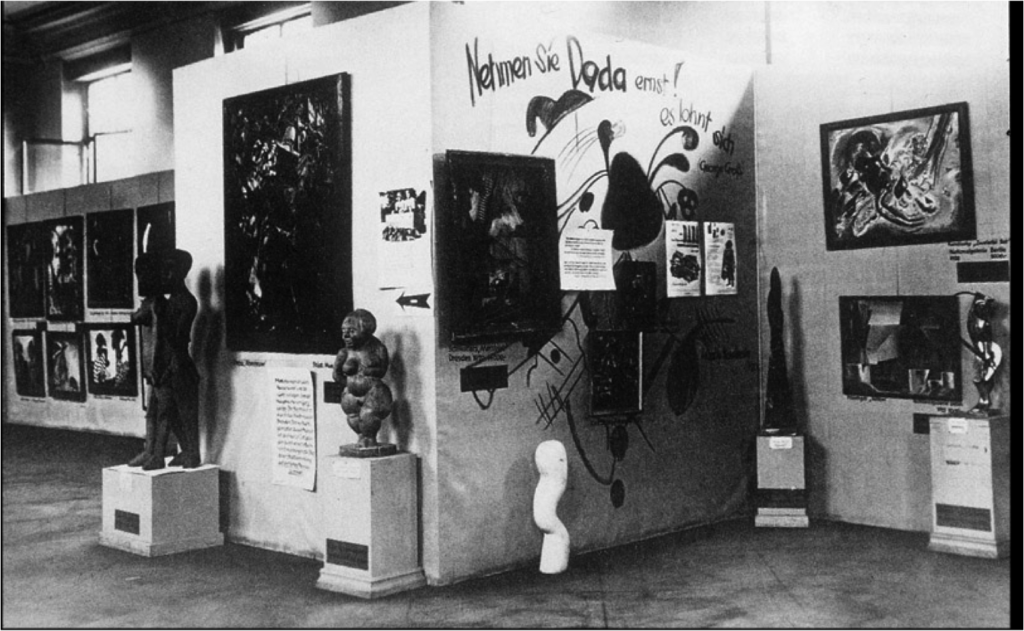

In 1937, Hitler had about 16,000 “degenerate” works of art gathered up from German museums by his henchmen. Among them were abstract, non-representational, and modern works by some of art’s most famous names, such as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, as well as works by Jewish artists. The exhibition booklet dictated that the show aimed to reveal the “philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement and the driving forces of corruption which follow them.” The show appeared thrown together with little care; the walls were plastered with graffiti, the artworks were arranged in a crowded manner, and the paintings hung crookedly. All to reinforce the belief that this art was disreputable. The museum even hired actors to mingle in the crowd and criticize the art.

Ironically, the exhibit attracted nearly 2 million visitors, even though its primary intention was to create disdain. The show then went on tour in Germany, where at least another million people had a chance to see it. While some attendees sided with the Nazis’ disapproval of the works and some who went simply for the scandal of it all, there were just as many, if not more, who attended the show because they felt it could be their last chance to see this type of work in Germany.

At the same time, Hitler organized a contrasting, supposedly “superior” show: The Great German Art Exhibition. This showcase of Hitler-approved art featured picturesque blonde nudes, idealized landscapes, and heroic soldiers—reflecting his own traditional, unoriginal tastes. However, drew far fewer visitors than expected, a stark contrast to Hitler’s vision for these grand displays. One could safely assume that the poor turnout bruised his ego.

After coming to power in Germany, Hitler supposedly had most of his paintings collected and destroyed. Yet several hundred still survive in collections around the world. Four of his watercolors are now owned by the United States Army, having been confiscated during World War II. Meanwhile, the International Museum of World War II in the U.S. holds one of the largest collections of Hitler’s art.

In Germany, it is legal to sell works bearing the infamous dictator’s signature, as long as they do not feature Nazi symbols. When they appear on the market, they almost always spark controversy. In a 2015 auction in Nuremberg, 14 works by Hitler sold for $450,000. While many criticized the sale of items connected to such a dark and troubling figure, the auction house defended the decision, citing the historical significance of the works.

However, historical and moral controversy isn’t all these paintings gather when they do come up for sale. Questions regarding their authenticity frequently arise as well. In 2019, two sales of Hitler’s work failed due to forgery concerns. In January, police raided Berlin’s Kloss Auction House and seized three watercolors believed to be forgeries. About a month later, more suspicions arose during a sale of Nazi memorabilia, including five paintings attributed to Hitler. Rumors of fraud combined with high starting prices ($21,000–$50,000) scared off potential buyers, leaving the works on the auction block. Nuremberg’s mayor condemned the sale, calling it “in bad taste.”

Heinz-Joachim Maeder, a spokesperson for the Kloss Auction House, noted that the high prices and media interest surrounding Hitler’s work are driven largely by the name on the signature, suggesting they have little, if any, artistic or art-historical value.

Stephan Klingen of Munich’s Central Institute for Art History explains that Adolf Hitler’s work is difficult to verify because his style is that of a “moderately ambitious amateur.” As a result, his creations hardly stand out among hundreds of thousands of similar works from this period. After all, Hitler mostly copied art he saw on postcards, emulated painters of the German school, and practiced whatever technique he could teach himself. This makes it difficult to identify elements unique to his style and, at the same time, makes it easier for skilled forgers to replicate his work.

In 1936, American art critic John Gunther commented on Hitler’s paintings:

They are prosaic, utterly devoid of rhythm, color, feeling, or spiritual imagination. They are architect’s sketches, painful and precise draftsmanship; nothing more. No wonder the Vienna professors told him to go to an architectural school and give up pure art as hopeless.

Others have gone even further. In 2019, Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz shared his opinion on the works in an interview with NPR:

Physically and spatially dead, generic academic realism, the equivalent of mediocre exercises in aping good penmanship. He was an adequate draftsman, utterly unimaginative, and made the equivalent [of] greeting cards.

In 2002, Frederic Spotts, author of Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics, showed several of Adolf Hitler’s paintings to an art critic, without revealing who had created them. According to Spotts, the critic’s first remarks were that the works were “quite good.” He then commented on the manner in which the humans in the paintings were portrayed, suggesting the creator’s “disinterest in the human race.” After decades of studying Hitler and his psyche, scholars believe his paintings nod towards his sociopathic tendencies. Writing in The Washington Post, Marc Fisher noted:

Is it possible to look at these antiseptic street scenes and see the roots of Hitler’s obsession with cleanliness and his belief that his mission in life was to cleanse Germany and the world of Judaism?

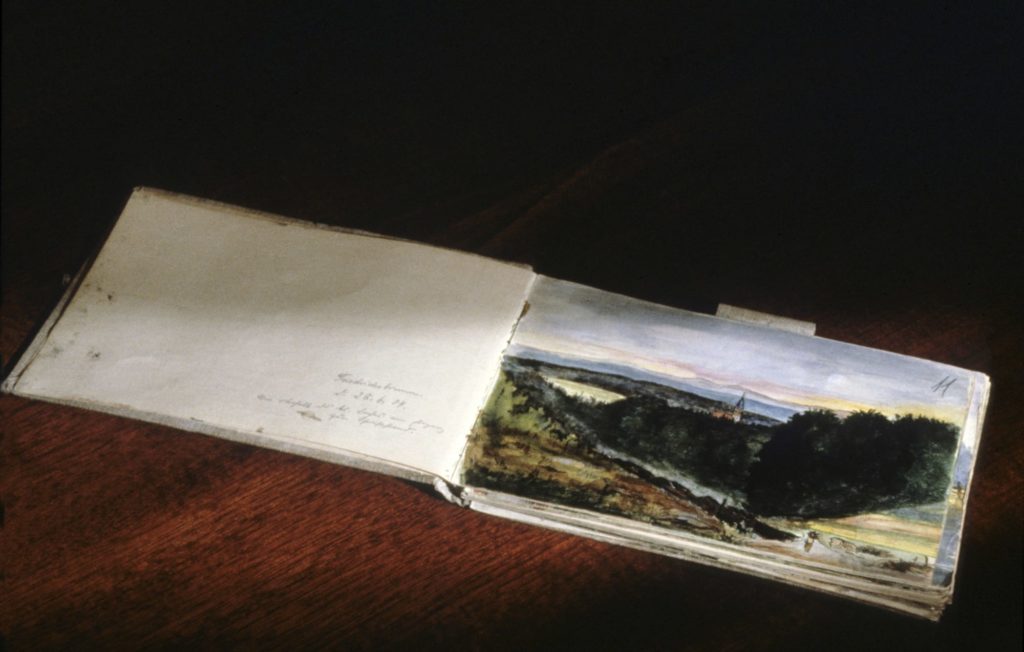

As Führer, Hitler continued to paint but kept his work private. In his book, Spotts notes that Hitler had limited artistic ability, lacked the technique of a trained student, and often failed to convey passion in his work. Nevertheless, painting remained a hobby he genuinely enjoyed, and he considered himself knowledgeable about art. He may have been delusional about art, as he was about many other things, but he was neither hypocritical nor certifiably insane in his approach to it. Spotts presents a substantial documentary record of letters, journals, and illustrations that make Hitler’s seriousness and dedication to art clear.

Adolf Hitler’s paintings can be interpreted as depictions of the “purified” state he envisioned. At the same time, his soft, idealized landscapes of old stone churches, country houses, castles, bouquets, famous landmarks, and snowy countrysides remind us of a difficult truth: even one of history’s most notorious figures had, in some ways, human interests.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!