Kettle’s Yard: A Tour Through Cambridge’s Modern Art Gallery

Kettle’s Yard, a somewhat modest home in the middle of Cambridge, UK, harbors an impressive art collection of predominantly modern and abstract...

Ruxi Rusu 24 June 2024

The Hitler’s Museum – originally in German called Das Führermuseum, was luckily an unrealized art museum within a cultural complex planned by Adolf Hitler for his hometown, the Austrian city of Linz.

It was supposed to be the greatest (both in terms of size and collection) museum in the world. This is why the greatest art plunder of the 20th century began in 1939. Pieces of art were in most of the cases confiscated or stolen by the Nazis from Jewish owners throughout Europe during World War II. The cultural district was to be part of an overall plan to recreate Linz, turning it into a cultural capital of the Third Reich. Therefore, it was to be one of the greatest art centers of Europe. The plan was to overshadow Vienna, for which Hitler had a personal distaste. The distaste was mostly because of his own failure to gain admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts.

The expected completion date for the project was 1950, but of course because of the fall of the Third Reich it was never finished. The only part of the elaborate plan which was constructed was the Nibelungen Bridge, which is still extant.

Hitler was an unfulfilled painter and loved art. As early as 1925, he had conceived the idea of a “German National Gallery” to be built in Berlin with himself as the director. But it was after the Anschluss with Austria that Hitler started to think of having his dream museum built not in Germany, but in his “hometown” of Linz in Austria. And he became obsessed with this idea.

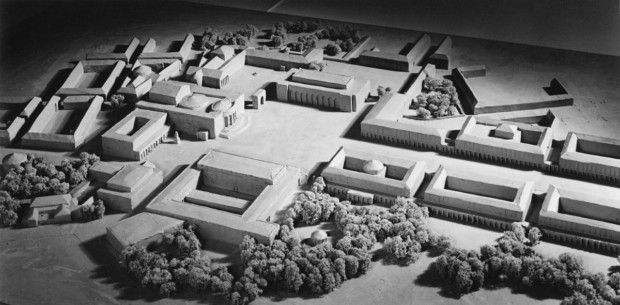

The museum complex, designed by Hitler’s architect Albert Speer, was to include an opera house, a hotel, a parade ground, and a theater. There would be a library, which could house as many as a quarter of a million volumes. Of course, the museum, with its 500 ft (ca. 150 m) facade with colonnades, would be in the monumental fascist Neoclassical style. The plan included about 36 kilometers of galleries (London’s Victoria & Albert Museum has about 8 kilometers of galleries). These galleries were to showcase 27,000 art objects. The model of the museum was set up in January 1945 in an air raid shelter (Führerbunker), located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. It was ready for viewing on February 9, 1945, when it was examined by Hitler.

Hitler visited the model frequently during his time living under the Reich Chancellery, spending many hours sitting silently in front of it. The closer Germany came to military defeat, the more the viewing of the model became Hitler’s only relief. An invitation to view it with him was an indication of the Führer’s sympathy.

According to one of Hitler’s secretaries, he was never tired of talking about his planned museum. It was often the subject at his regular afternoon teas. He would expound on how the paintings were to be hung: with plenty of space between them, in rooms decorated with furniture and furnishings appropriate to the period, and how they were to be lit. No detail of the presentation of the artworks was too small for his consideration.

The art collection for the planned museum in Linz was accumulated through several methods, not only by theft. Hitler himself sent his soldiers on trips to Italy and France to buy artworks, which he paid for with his own money. The money was acquired from the sales of Mein Kampf, along with real estate speculation on land in the area of the Berghof – Hitler’s mountain retreat in the Bavarian Alps. Additional royalties came from Hitler’s image used on postage stamps.

On June 21, 1939, Hitler set up the Sonderauftrag Linz (Special Commission: Linz) in Dresden and appointed Dr. Hans Posse, director of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, as a special envoy. The Sonderauftrag not only collected art for the Führermuseum, but also for other museums in the German Reich, especially in the Eastern territories. The artworks would have been distributed to these museums after the war. The Sonderauftrag in Dresden consisted of approximately 20 specialists: curators of paintings, prints, coins, and armor, a librarian, an architect, an administrator, photographers, and restorers.

From the autumn of 1940 onward, Hitler regularly received (often as a Christmas present) annotated photo albums full of confiscated art that could be featured in the Führermuseum. A total of 31 albums were prepared, of which 19 survive to this day.

The Allies found a number of hiding places for looted art, including the famous salt mine in Altaussee, in the Austrian Alps. It contained some 12,000 stolen artworks, including the famous The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck. This piece was the number one target that Hitler wanted as the centerpiece for his museum. Because of both its fame and importance, and also because it had been forcibly repatriated to Belgium from Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, seizing it back would right this perceived wrong against the German people.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!