Józef Chełmoński in 10 Paintings: Capturing the Spirit of Rural Life

Józef Chełmoński masterfully portrayed life in the Polish countryside. His paintings reveal a subtle connection between human and nature,...

Kinga Dobosz 21 August 2025

Grant Wood’s 1930 painting American Gothic helped establish the Regionalist movement and shatter the big-city monopoly on fine art. His work championed the understated elegance of rural living at a time when the United States was working through the tumult of the Great Depression.

Simultaneously, Grant Wood’s quiet queerness conflicted with the rugged farmboy-turned-artist success story commonly assigned to him in the press. Grant Wood was both wholesome Americana and a threat to traditional values. These 10 works will take you through his impactful career.

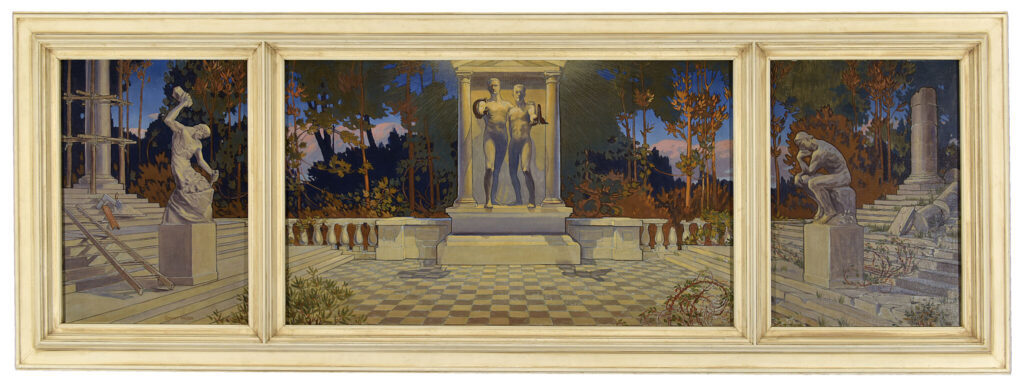

Grant Wood, The First Three Degrees of Freemasonry, 1921, Iowa Masonic Library and Museum, Cedar Rapids, IA, USA. Whitney Museum.

Grant Wood painted this triptych for the Anamosa, Iowa, chapter of the Freemasons, a fraternal organization to which he briefly belonged. In it, he represents several levels of Freemasonry: apprentice, fellowcraft, and master mason. According to a Freemason pamphlet printed in the 1940s, the right-hand side represents the apprentice concerned about the temple’s restoration. The left side shows the completed building and represents fellowcraft, while the center depicts brotherhood.

The painting is based on important works of classical sculpture. The leftmost section references Albin Polasek’s Man Carving his Own Destiny. The statue on the right is Rodin’s The Thinker. The central figures resemble Michelangelo’s David in their hip tilts. By steeping his painting in artistic tradition, Wood gives grandiose importance to the brotherhood of the Freemasons.

Grant Wood, Calendulas, 1928–1929, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Cedar Rapids, IA, USA.

Born into an Iowa Quaker family in 1891, Wood grew up amidst cornfields and farm animals. He considered his dad “more god than father,” an archetype of the hard-working, stoic patriarch. Wood told the Los Angeles Times, “Painting was about on a level with tatting [lace making] in the opinion of my fellow Iowans.”

Wood, however, longed to be an artist and spent his high school years illustrating school publications and creating theater set designs with his friend Marvin Cone. Through odd jobs, Wood saved enough money to study art in Paris, where Impressionism was in vogue. His early works reflect his European training.

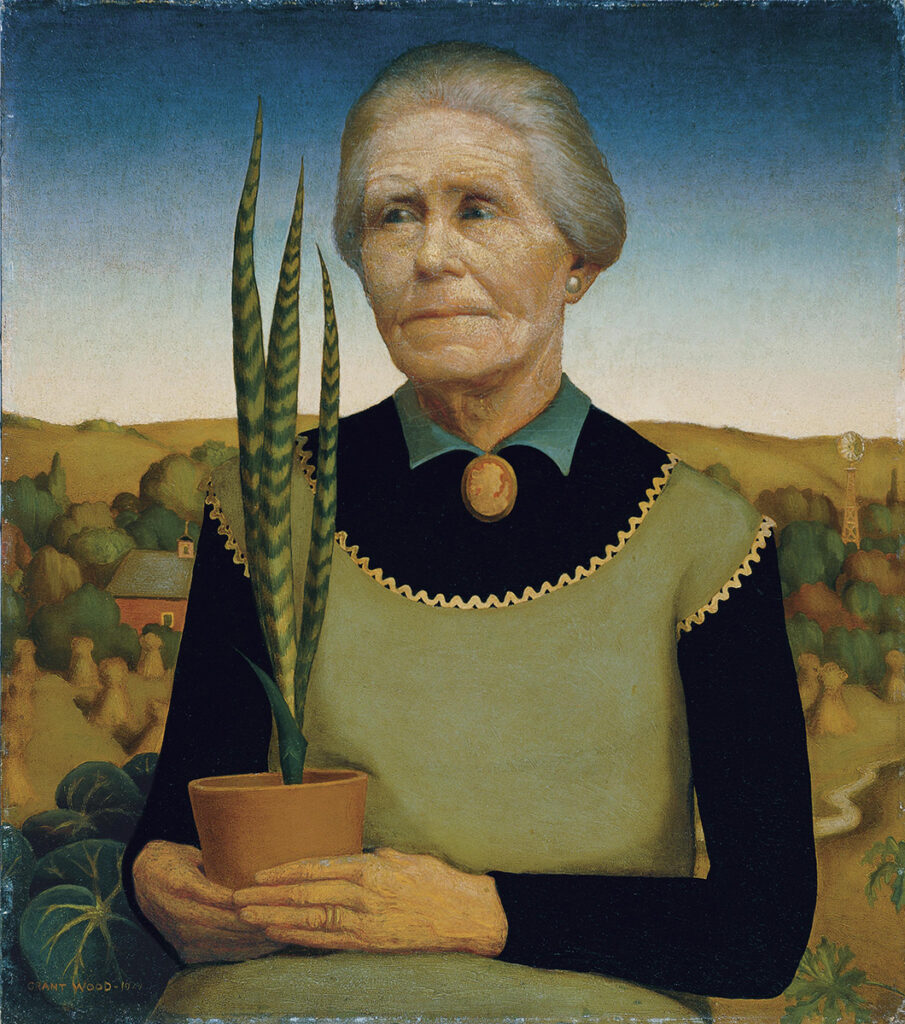

Grant Wood, Woman with Plants, 1929, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Cedar Rapids, IA, USA.

I spent 20 years wandering around the world hunting “arty” subjects to paint. I came to Cedar Rapids, my hometown, and the first thing I noticed was the cross-stitched embroidery of my mother’s apron.

Wood painted this portrait of his mother shortly after returning from Europe. He’d been heavily influenced by the work of Jan van Eyck. Wood’s portrait subjects display an uncanny rigidity typical of Van Eyck’s work. Wood’s landscapes often look as if viewed through a convex lens, reminiscent of the mirror in Van Eyck’s masterpiece The Arnolfini Portrait.

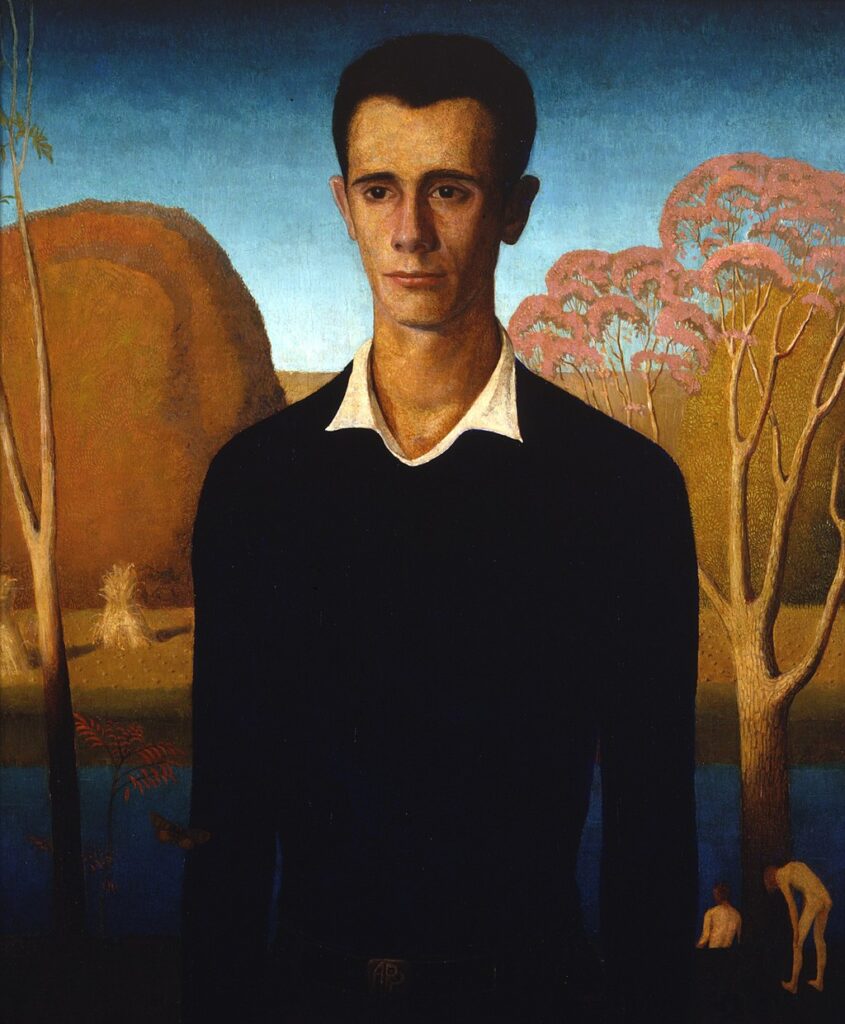

Grant Wood, Arnold Comes of Age, Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, NE, USA.

At age 18, Arnold Pyle began working as an assistant to his 36-year-old mentor Grant Wood. Pyle also served as a model for the shirtless figure in Wood’s stained-glass window at the Veterans Memorial Building.

Gifted to its subject upon his 21st birthday, this painting is often considered Wood’s most gay-coded work. The nude bathers in the right-hand corner of the painting are certainly suggestive. Also, art historian Anya Ventura notes the butterfly at Pyle’s right elbow, a symbol of homosexuality at the time.

Wood’s feelings toward Pyle are often described as paternal, though this painting suggests more. There’s no evidence that any romantic feelings Wood may have had were ever returned, however.

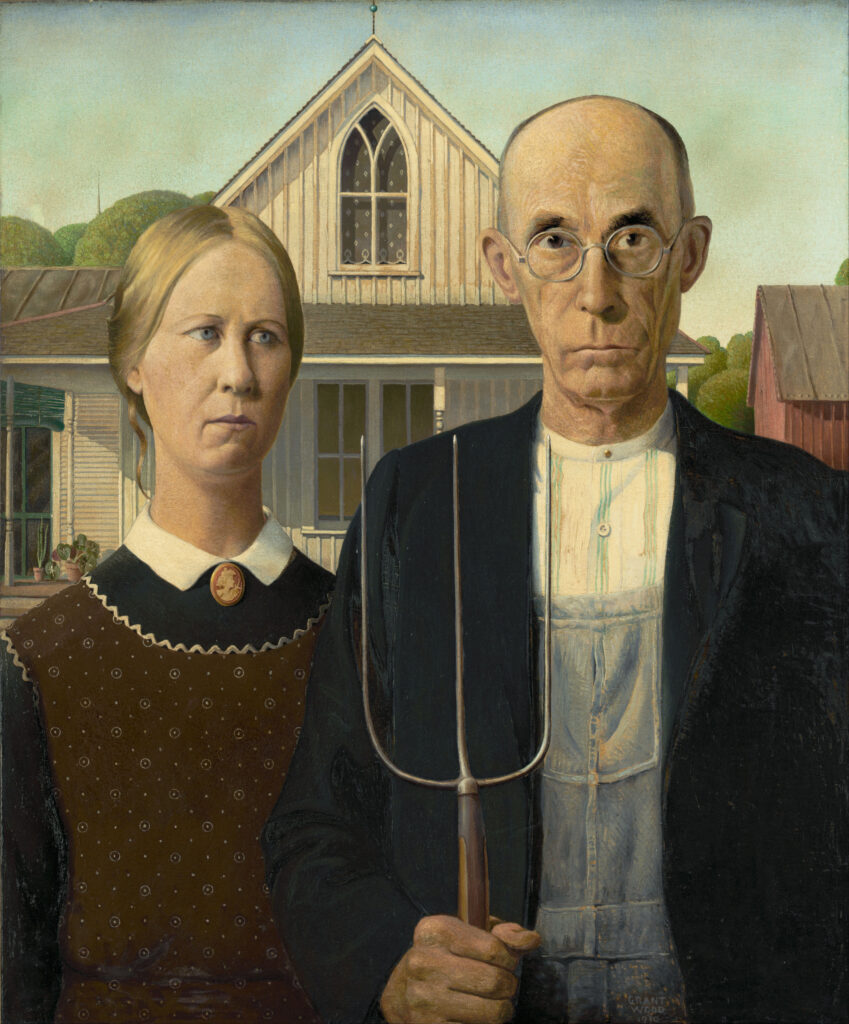

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

If you know of Grant Wood, it’s likely because of American Gothic, the iconic painting referenced repeatedly in pop culture parodies, including the opening sequence of American Housewives and on The Simpsons.

This painting debuted at the Art Institute of Chicago and helped kick-start the American Regionalist movement, which also included artists Marvin Cone, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry. The Regionalists portrayed the hard-working people, small towns, and rural landscapes of the American Midwest.

When first shown in 1930, American Gothic created a sensation. However, viewers could not agree as to whether it portrayed a simple couple out of touch with the modern world or salt-of-the-earth Depression-era farmers. Did it skewer simple people or celebrate them?

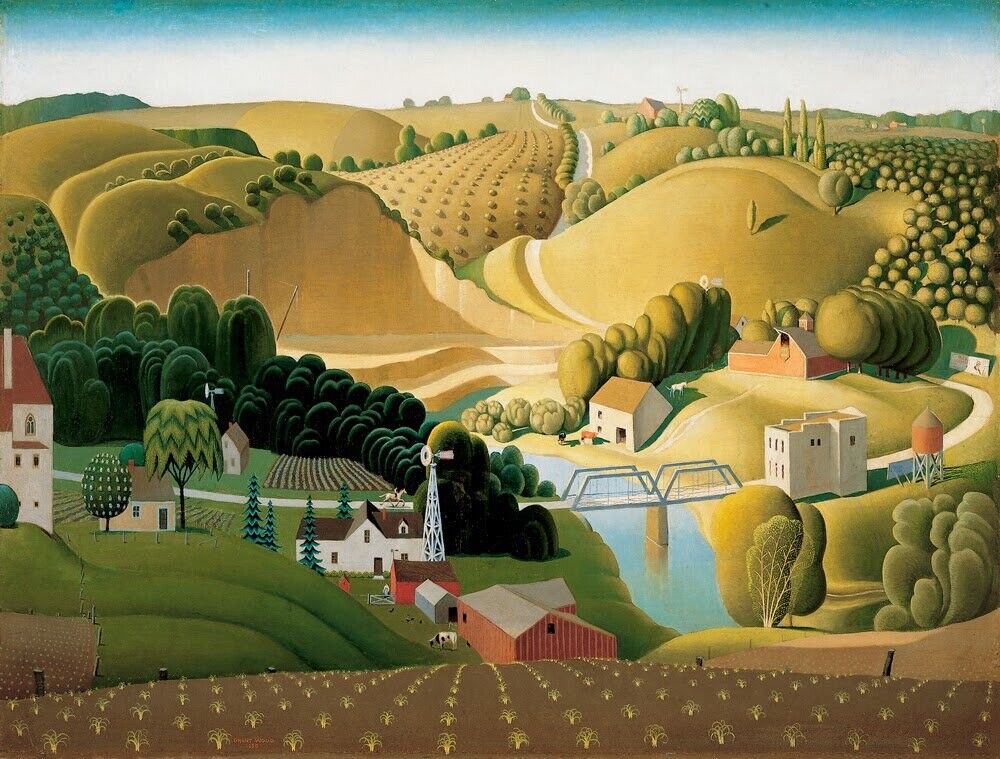

Grant Wood, Stone City, Iowa, 1930, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE, USA.

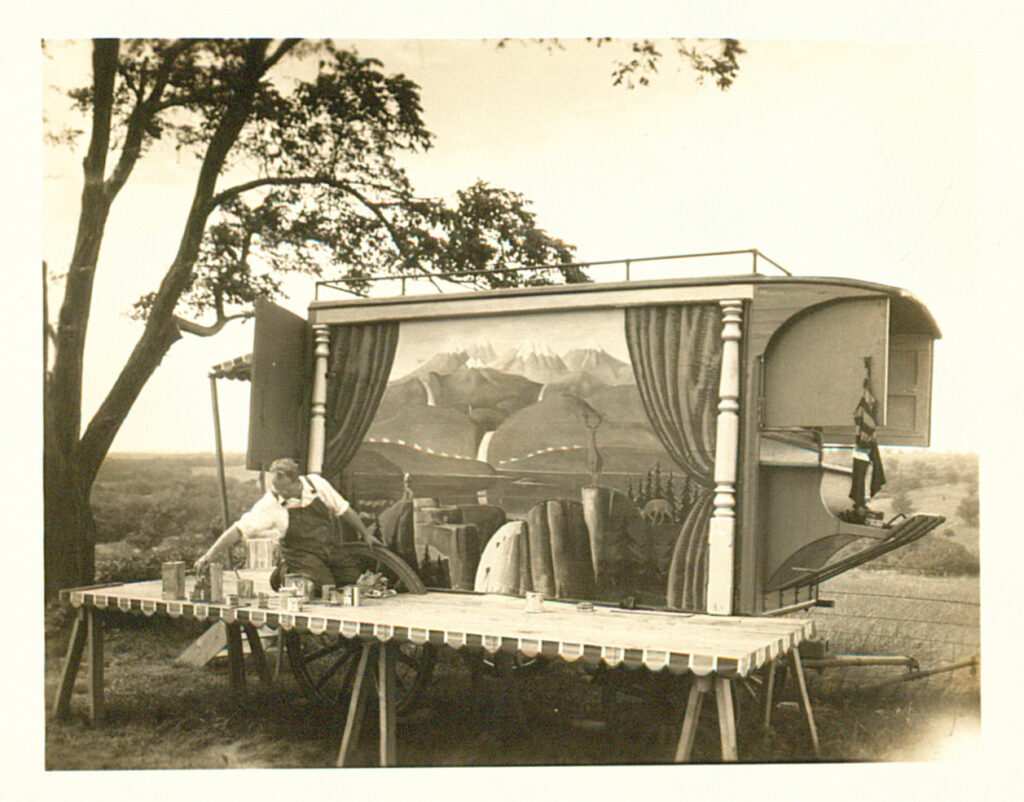

In 1932, Wood helped establish the Stone City Arts Colony, where Marvin Cone also served as an instructor. The colony lasted just two years due to financial challenges. Archives of American Art called it a place where artists could “study together, work together, and play together.” Many colony residents lived in old ice wagons, some of which they painted with as much care as was given to any canvas.

The colony, nestled in the landscape shown in this painting, provided a freedom unlike what Wood could find elsewhere in Iowa. John Bloom shared Wood’s wagon the first summer, Charles B. Keeler the second. Arnold Pyle also resided in the colony.

Grant Wood painting an ice wagon in Stone City, Iowa, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, USA.

In this landscape, Grant Wood bends perspective to show planted fields, a small town, and the expanse of rolling hills in the distance. Wood employed this technique in several other paintings in later years, including the next one on this list.

Grant Wood, The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, 1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

This painting also showcases an aerial view used in several of Wood’s landscape paintings. Art historian Jason Weems claims this was likely influenced by Wood’s work as a camouflage artist during World War I. The artist studied numerous aerial photographs as part of his efforts to make artillery and other military assets harder to identify from the air.

In this scene, Wood illustrates the famous midnight ride of Paul Revere, which is as much an American fable as a historical event. Wood plays with the idea of American myth-making again in his 1939 painting of George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, a story concocted by Parson Weems (no relation to Jason Weems). Both paintings helped solidify Wood’s place as a recorder of American iconography, the second with a knowing nod to its dishonesty.

Grant Wood, Death on Ridge Road, 1935, Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA, USA.

In this painting, Wood again takes a bird’s-eye view and bends perspective, but this time, he shows motion, foreboding danger, and immediacy. It’s easy to see a connection to the Italian Futurist movement happening at the time.

As automobiles became more prevalent in the 1930s, so did car accidents. Ridge Road outside of Stone City was notoriously dangerous. The scene here closely resembles Jay Sigmund’s accident while traveling to visit Wood at the Stone City Arts Colony in 1933. Shortly after his car wreck, Sigmund penned the poem Death Rides a Rubber-Shod Horse.

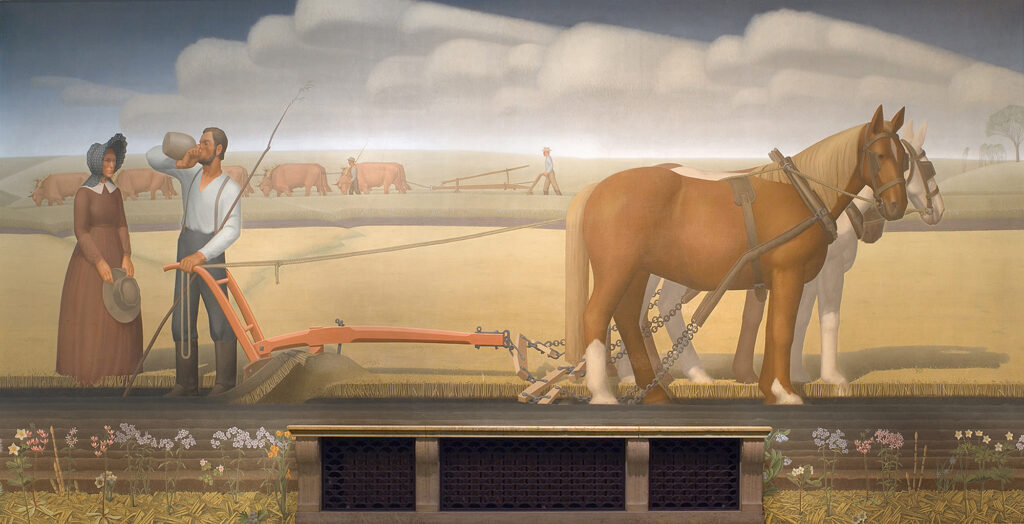

Grant Wood, Breaking the Prairie, 1936–1937, Parks Library, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA. Public Art Archive.

Because these two murals are both in the Parks Library at Iowa State University, they occupy only one spot on this list. The works are so large and expansive, they’re best captured through video rather than still photos (see below).

In 1934, Wood was hired as the head of Iowa’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), a large-scale federal program providing jobs for Americans through public works projects, including public art. This influx of federal money resulted in an explosion of mural work in post offices and other federal buildings across the country.

Each mural told a story about a specific state or region. The national effort fit perfectly with the Regionalist movement Grant helped to establish. Other pillars of Regionalism, Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, received WPA money, as did several of Wood’s Stone City friends.

Grant Wood’s When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow (1934) and Breaking the Prairie (1936–37), Whitney Museum YouTube. Accessed: Feb 22, 2018.

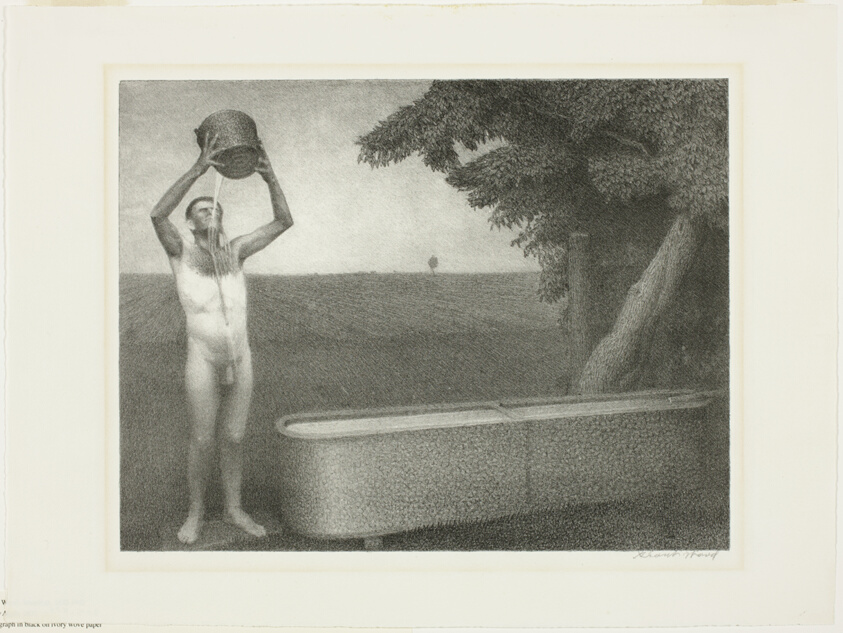

Grant Wood, Sultry Night, 1939, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Wood produced a limited number of copies of this lithograph, which were sold and distributed by a private gallery through the United States Postal Service. However, citing obscenity, the USPS banned the shipment of the works. Wood claimed the lithograph showed a normal scene from farm life and a memory from boyhood.

A later biography (R. Tripp Evans, Grant Wood: A Life, Deckle Edge 2010) suggests the model was a colleague from Wood’s time at the University of Iowa who lived with the artist during the summer. Wood made a painting of the image too, but later cut out the nude figure, leaving only the tub and the landscape. Despite censoring Wood in 1939, the USPS released two stamps featuring Grant Wood’s artwork in the 1990s.

As the United States pulled out of the Great Depression and into World War II, Regionalism faded. Wood died of pancreatic cancer in 1942, and the WPA ended the following year. Abstract Expressionism became the new American art movement, and radical individualism contrasted with Socialist realism as the Cold War began. Abstract Expressionist Arshile Gorky famously dismissed Regionalism as “Poor art for poor people.”

However, Grant Wood’s art endures. He showed Middle America as no artist had done before or since. His work calls up the American Dream that if you are righteous and work hard, you’ll reap a good harvest.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!