The Frank Stella You Thought You Knew

You may know Frank Stella from the brightly colored, shaped canvas paintings in his Protractor series from the late 1960s to early 1970s. However,...

Marva Becker 11 July 2024

27 November 2023 min Read

Have you ever seen a pig covered in an oriental carpet, a cement truck with Gothic motifs, or a silver DNA string with crucifixes? These are the utopian constructions of Wim Delvoye, a Belgian conceptual artist.

When I reflect on Wim Delvoye’s artworks, I notice that he is an attentive observer of today’s world and questions art with his controversial projects. He may be inspired by current scientific innovations, but he likes to go back to older crafts such as ironwork and stained glass to express his ideas. Delvoye once started with imaginary maps and manipulated photos and has managed to bring his work to a height where an entire team of specialized craftsmen and scientists works on his gigantic pieces of art. Some of his works have stirred up quite a controversy.

Wim Delvoye likes some contradiction in his work, hence his great interest in pigs. They are loved because they symbolize abundance (especially in China) but at the same time, they also represent dirtiness. For these works, he uses molds which he later has the casts covered in a luxurious oriental carpet. The designs and colors are different and each model seems to have a real personality.

The pigs each have a separate attitude and thus seem to fit perfectly in a classical interior. At first glance, they look like lovely pets who have traded their muddy stables for a more serene environment. This is especially true for the sitting pig which, in a cynical joke of Delvoye’s, resembles the lion as depicted in heraldry. And did I mention that the artist has given them all a first name?

From 1998, Wim Delvoye tattooed live pigs with an unusual mix of Disney characters, symbols from motorcycle culture, and even a Louis Vuitton logo. After the pigs died, the skins were preserved and some were sold to Chanel, who made handbags from them. This might shock you, especially when you learn that the artist had moved the project to China, where animal welfare laws are more lax. He was forced to move because he received a lot of criticism from animal rights associations in Belgium. In his defense, Delvoye claimed that the pigs were much better off with him than on a farm where they would end up in the food industry.

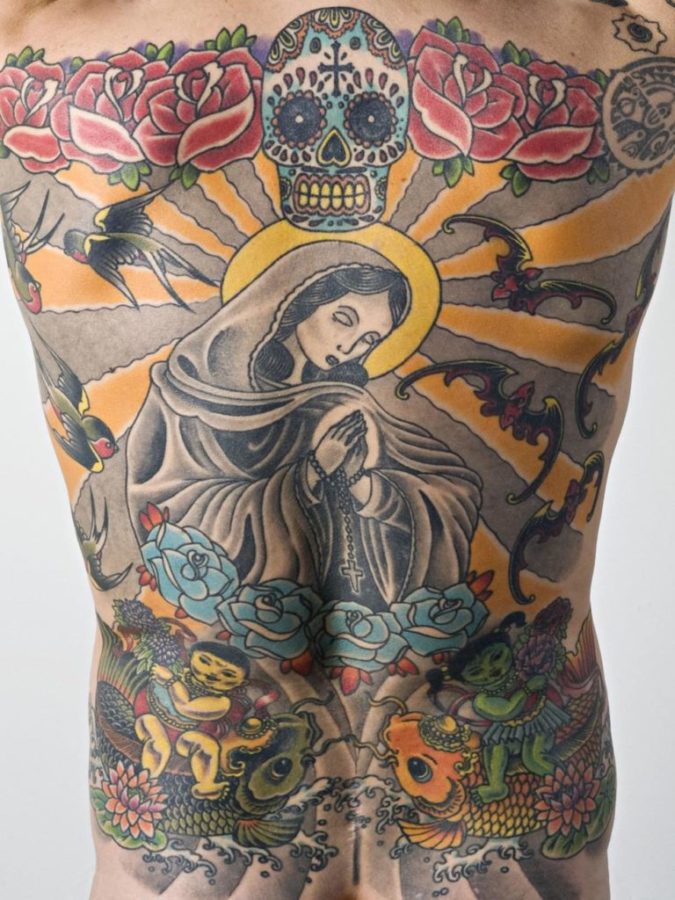

What may seem even stranger is that Delvoye also tattooed the back of a man called Tim Steiner. The tattoo depicts a praying Virgin Mary with a rosary amid beams of light, surrounded by soaring birds and roses, an assortment of skulls, and two children riding Koi fish. The tattoo took Delvoye 40 hours to complete, over the span of two years. The German collector Rik Reinking admired Steiner’s ink so much that he bought the tattoo. He closed a deal with Steiner, paying a third of the purchase price in advance, in exchange for participating in art exhibitions. Steiner also agreed that upon his death, he would be skinned and his back art stretched, preserved, and framed for Reinking’s art collection.

The jump from tattoos to medical science would be a big one for most people, but not for Wim Delvoye. In his Twisted Works, he confronts medical science with religion. When showing his works, Delvoye doesn’t give much explanation. He wants people to interpret the pieces by themselves and the only guidance that he gives to his public is the following: “We want to explain something that is beyond everyday life, but to explain it, we use the most everyday things possible”.

In Double Helix, he is interpreting the gift of life via a DNA string that is embodied by multiple crucifixes. Most people in the Western world know the crucifix as a Christian symbol of the resurrection of Jesus. This is exactly how Delvoye tries to make the connection visible between a well-known religious image and a sophisticated DNA string, which is still a medical mystery for many people.

In Twisted Tires, Wim Delvoye explores the confrontation of art with an everyday object. He processed a rubber bicycle tire, which is linked to the national sport of his home country, cycling. The artist also confronts craftsmanship with cutting-edge technology. The apparently hand-twisted bicycle tires are actually the result of a technological process. These assemblies of bicycle tires are complex stainless steel sculptures made from 3D prints before being carefully painted and chromed.

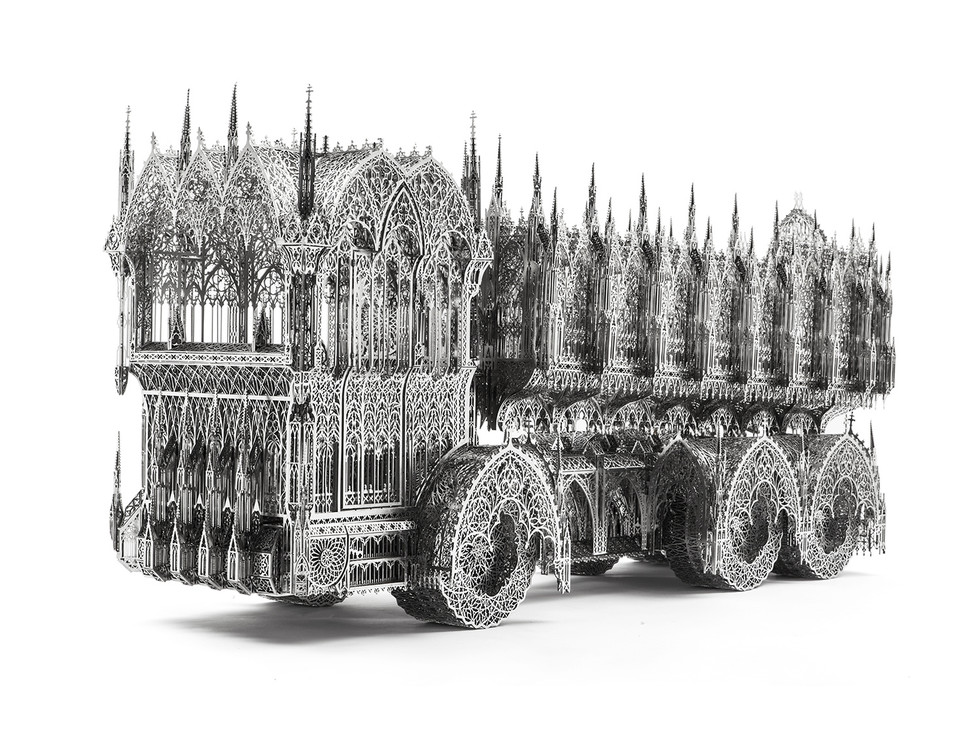

Wim Delvoye’s interest in Medieval history began in 1989 when he started his series of shovels painted with coats of arms. Later, he became inspired by the architecture of the 11th-century Gothic cathedral of Lincoln, England. With the shovels on his mind, he started to design construction vehicles such as cement trucks. Like a conductor of an orchestra, he mobilized the best craftsmen and obtained very refined works of art that make you say “Oh, I never thought a cement truck could look like this…”

Delvoye’s interest in Medieval art also resulted in the creation of football goals in stained glass with religious and folklore motifs. To give you even more of an idea of the unstoppable mind of the artist, these works of stained glass brought him, again, to the field of medicine. This time he included X-ray photographs in stained glass. Crazy, right?

Wim Delvoye is clearly a provocative conceptual artist. Following his tattooed pigs, he was again confronted with heavy criticism after announcing his original Cloaca machine in 2000. Why was it considered provocative? Actually, he aimed to create a complex and difficult-to-build machine that was completely useless. Contradictory, you might say? In fact, he was inspired by the Dadaist artist Piero Manzoni, who in 1961 produced canned shit (Merda d’Artista), supposedly his own.

However, Delvoye didn’t want to limit himself to a series of cans. He wanted to create something much more complex: a machine that mimics the human digestive system. The twelve-meter-long device consists of six transparent laboratory flasks that simulate the functions of the stomach, pancreas, and intestines. The result at the end of the production line is, more or less, the same as Manzoni’s work, but Delvoye shows the entire machinal digestion, outside of a human body. For two years, he worked silently with scientists and engineers on the technical machine.

A funny anecdote is that the Cloaca is fed three times a day and, just like a human, proved to be averse to certain foods, suffering from constipation after eating too much mashed potato. Consequently, the museum staff was asked to adapt the diet.

The purpose of the Cloaca machine went beyond the realm of art and questioned our economic system when Delvoye attempted to list it on the stock market. It was never listed, but his ambition evokes Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times as an ironic comment on today’s economic set-up. Just as in Chaplin’s movie, the artist criticizes mass production, and even today’s marketing, by realizing a series of Cloaca machines. Next to the original he produced the Turbo version, the Quattro version, the Mini, the Cloaca N°5 (a reference to Chanel) and even a travel kit Cloaca.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!