Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 10 June 2024

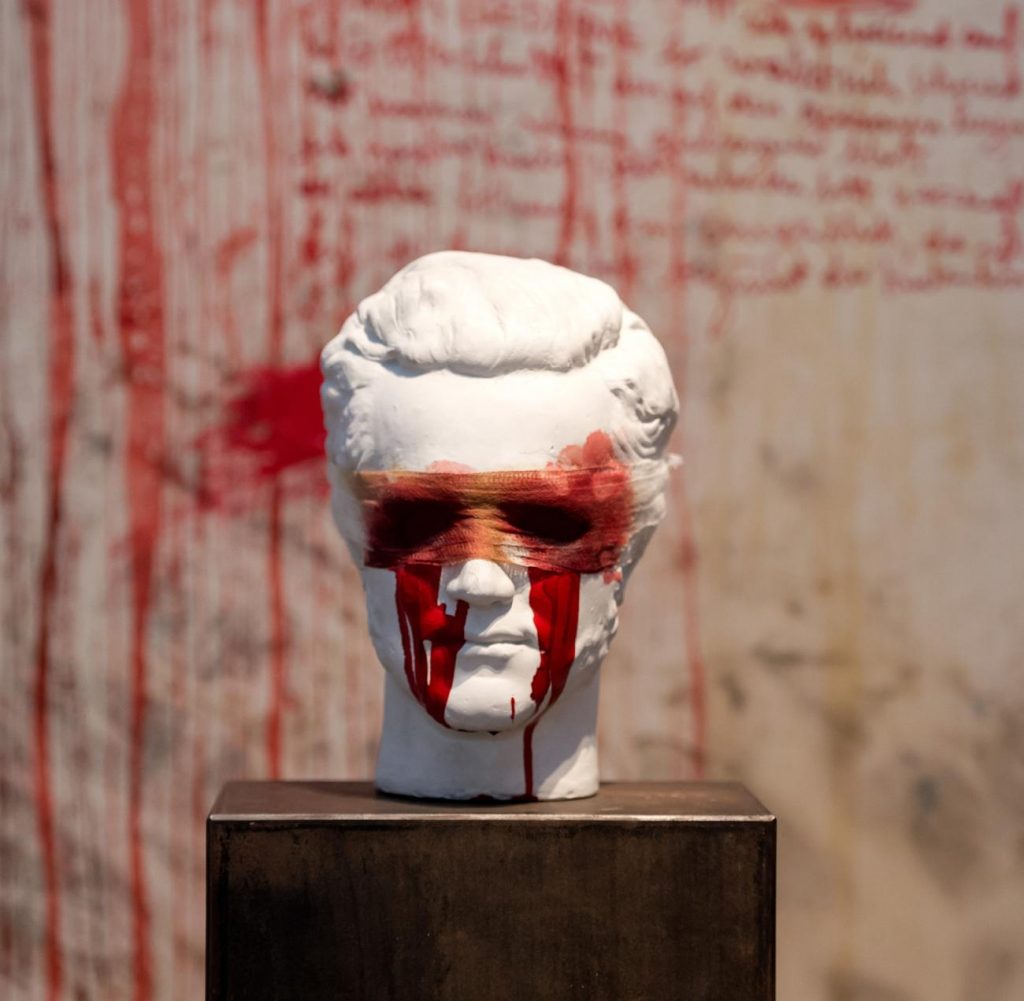

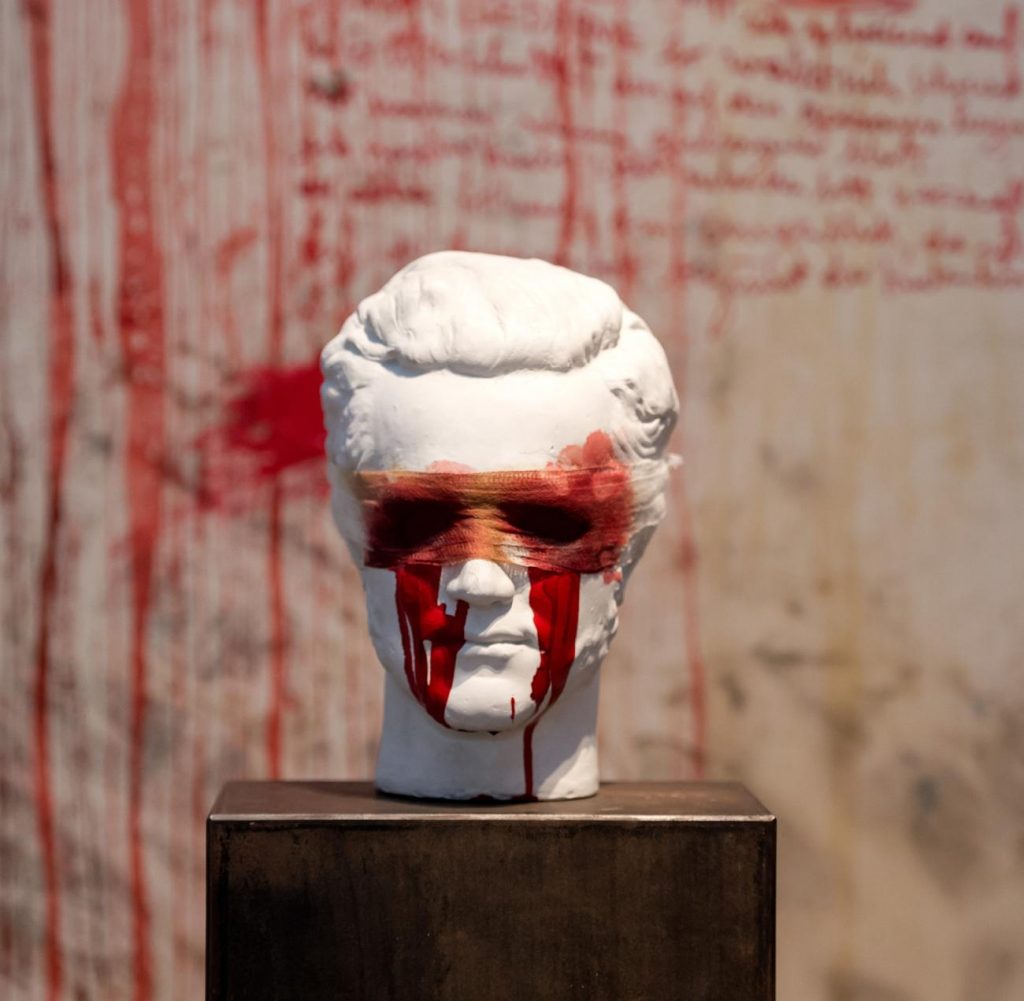

Naked bodies, violence, and destructive art. The term Viennese Actionism refers to a radical and explicit form of performance art that developed in the Austrian capital during the 1960s. Mainly consisting of four members which through their performances or “actions” as they called them, aimed to make taboo-breaking, often illegal, and sometimes repellent statements that expressed violent dissatisfaction with what they saw as the uptight, bourgeois government and society of post-World War II Austria.

Viennese Actionism was a short and violent movement in 20th-century art active between 1960 and 1971. It can be regarded as part of the many independent efforts of the 1960s to develop performance art, such as Fluxus, action painting, happenings, etc. Its main four participants or “Actionists” as they were called were Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, Rudolf Schwarzkogler, and Hermann Nitsch.

The work of the Viennese Actionists developed concurrently with other avant-garde movements of the era that shared an interest in rejecting object-based art practices. The practice of staging precisely scored actions in controlled environments or before audiences creates similarities with the American Fluxus or the above-mentioned happenings and is a forerunner to performance art.

Viennese Actionism started with painting but they wanted to move beyond. The artists soon realized that they want to do something beyond the canvas and return the figure to their art. But instead of representing the figure, the artists’ own bodies, as well as those of others, became their medium of expression. The human body became a three-dimensional action painting and through their elaborately staged performances, or “actions“, which were documented, they strove to break down the defenses, rationalizations, and inhibitions of the audience as much as remove the barriers between art and life.

All of them witnessed the ravages of World War II and its aftermath, though only one of them, Otto Muehl, was old enough to fight, entering the Wehrmacht in 1943 at the age of 18. In the decades following the war, they pursued an idiom that evolved from Abstract Expressionist-influenced paintings to blood-drenched rituals that inverted every sexual, social, and hygienic taboo.

Viennese Actionism’s goal was not simply to use radical means of expression, but also to battle a much larger taboo: discussing Austria’s role in World War II. The postwar Austrian Republic saw itself as a victim of Nazism, not as a perpetrator. The official repression of memories of the war years prompted a strong reaction from Actionists, who had themselves experienced the horrors of war. The Actionists thought Austrians were suppressing memories of the unspeakable atrocities committed by the Nazis in their country and were trying to force people to face these traumas head-on through their art.

The group was prepared to act illegally in pursuit of their art. Often, brief jail terms were served by participants for violations of decency laws, and their works were targets of moral outrage. Hermann Nitsch, for example, was arrested and imprisoned numerous times for breaking Austrian indecency laws by masturbating and enacting violent sexual scenes in his performances. Günter Brus began serving a six-month prison sentence after an action called Art and Revolution in Vienna at which he simultaneously covered his body with his own feces and sang the Austrian national anthem with Otto Muehl, who was in prison for eight months after his participation at the same event in 1968. It was through pushing their actions beyond legal limits that they cemented their reputation as the most extreme of 20th-century performance artists.

While the nature and content of each artist’s work differed, there are distinct aesthetic and thematic threads connecting the Actions of Brus, Muehl, Nitsch, and Schwarzkogler, even though there was no consciously developed sense of a movement or any cultivation of membership status in the group. As Herman Nitsch submitted, Viennese Actionism was never a group. A number of artists reacted to particular situations that they all encountered, within a particular time period, and with similar means and results.

Actionists were frustrated by what they saw as the limits and conventionality of abstract painting. Instead of paint, they used organic materials such as blood, urine, milk, and animal entrails, and instead of canvas, they used naked bodies as sites or surfaces in their carefully controlled performances. The use of the body as both surface and site of art-making seems to have been a common point of origin for the Actionists in their earliest departures from conventional art practices in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Brus’s first action piece Ana was set in a white room, possibly a studio or house, where the artist covered his wife’s body in paint, and then painted on the walls and threw paint around, including on himself. The whole action has been documented in a 3-minute silent film by the Austrian avant-garde filmmaker Kurt Kren.

In choppy, disorienting scenes, the viewer sees various shots of a female nude (his wife) and the face of a male figure (himself), scenes of an interior, that include a cluttered table and a bicycle. Paint is smeared and thrown in such a way as to suggest blood and violence even though the film is black and white and the exact color cannot be confirmed.

Other Actionists like Rudolf Schwarzkogler, Nitsch and Muehl created variations on that theme, using liquids, foodstuffs and blood besides paint.

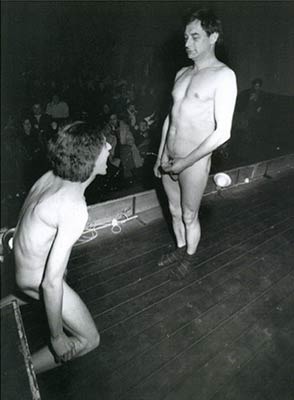

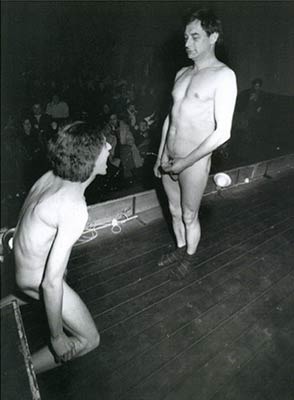

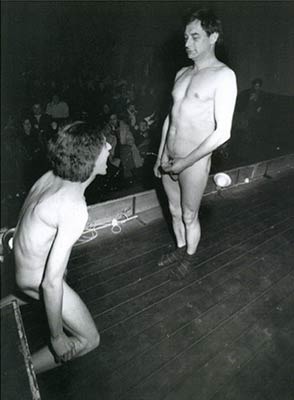

Muehl first performed his Piss Aktion, in which he stood naked and urinated into fellow Actionist Günter Brus’s mouth live on stage, at the Hamburg Film Festival in 1969, and it is remembered for its intentional and extreme violation of society’s norms.

Piss Aktion is one of the most notorious demonstrations of art merging with life and breaking free of the walls of the art museum. In the obscene daring of this action, Muehl was moving beyond what he referred to as the more bourgeois happenings into what he labeled direct art, in which he used bodily functions (such as urination) as tools for expressions of intense, pent-up energy and taboo-breaking.

My body is the intention. My body is the event. My body is the result.

Günter Brus, Nervous Stillness on the Horizon, 2005.

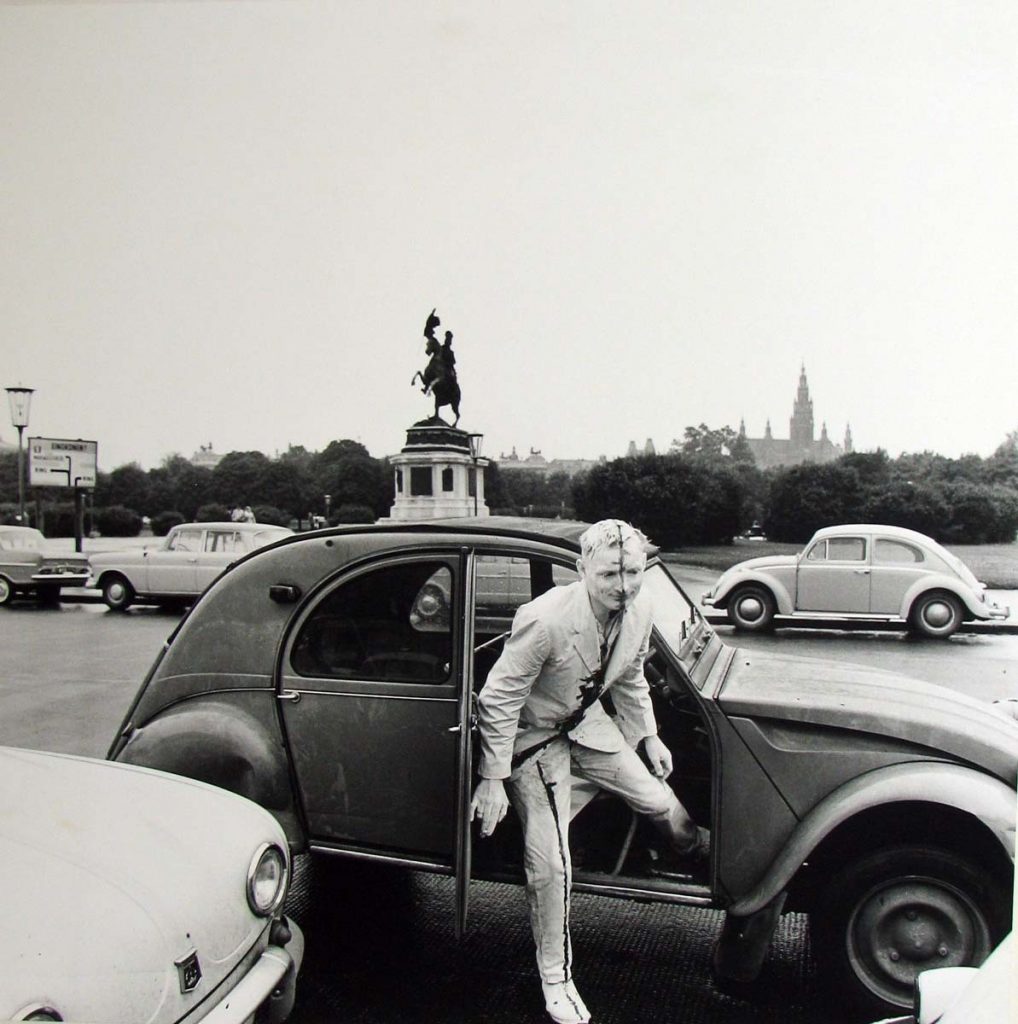

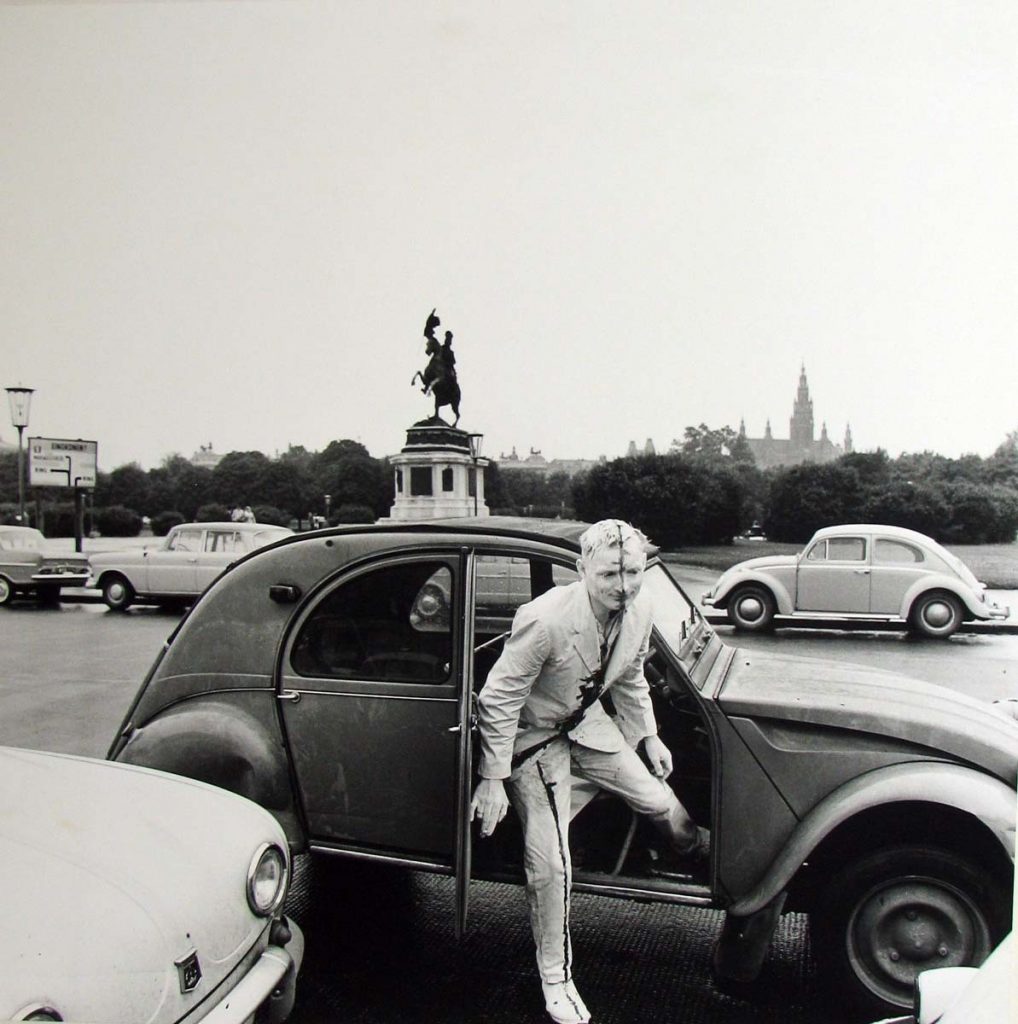

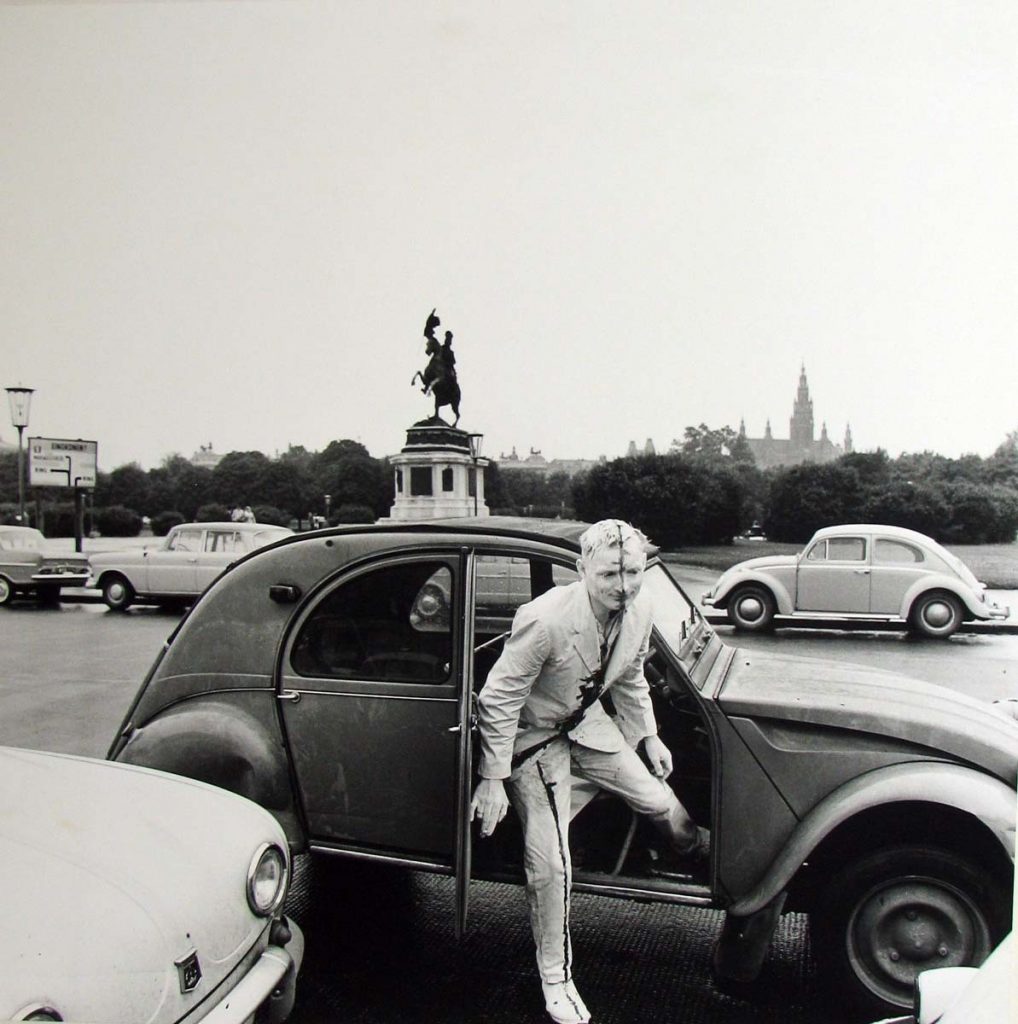

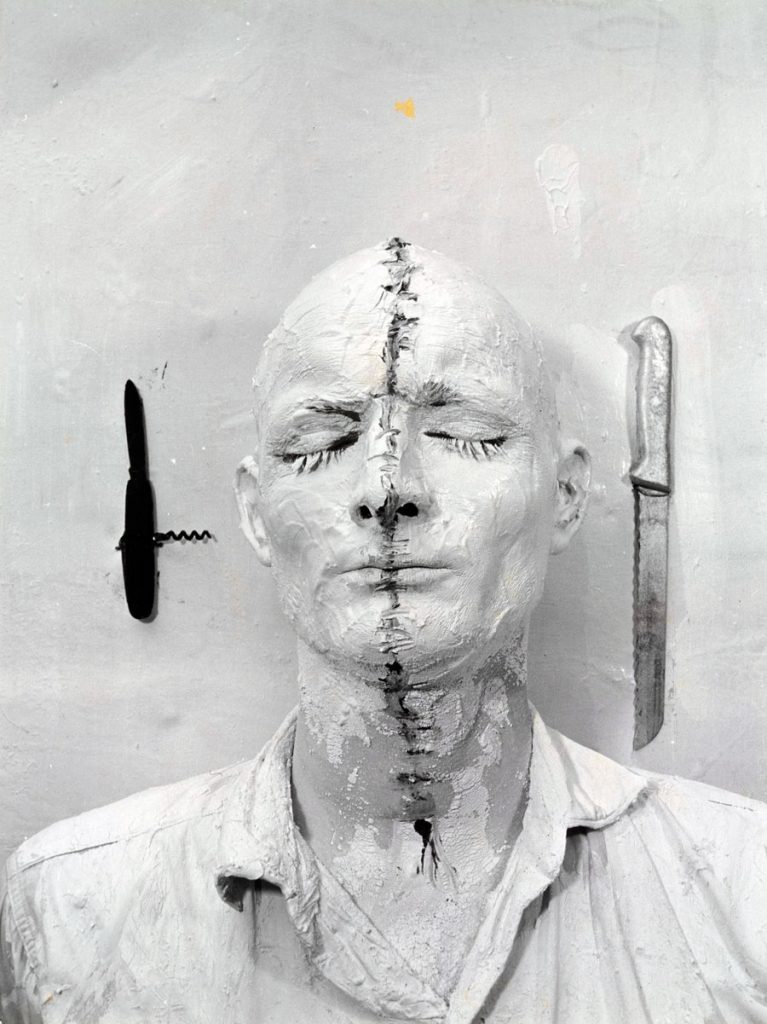

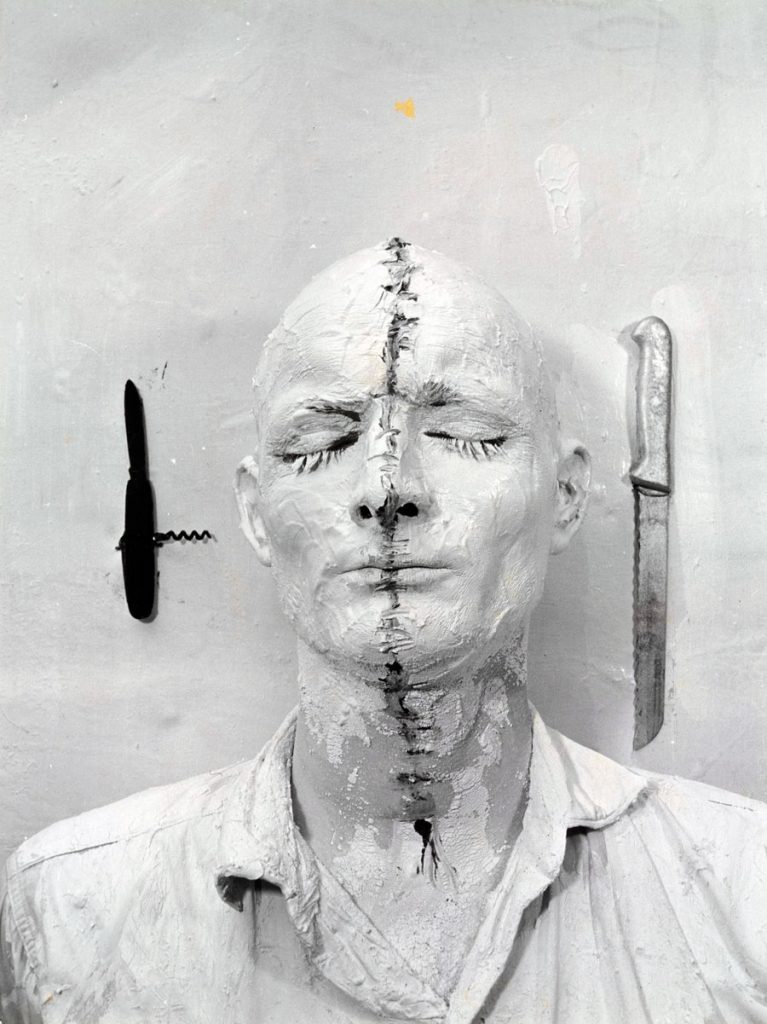

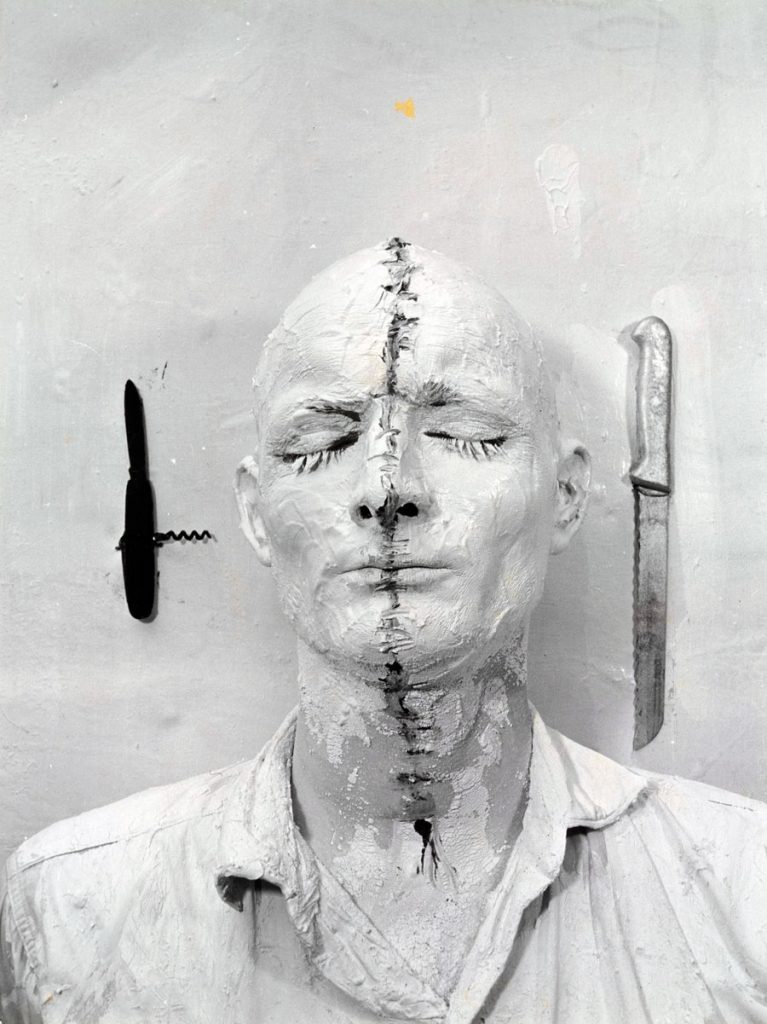

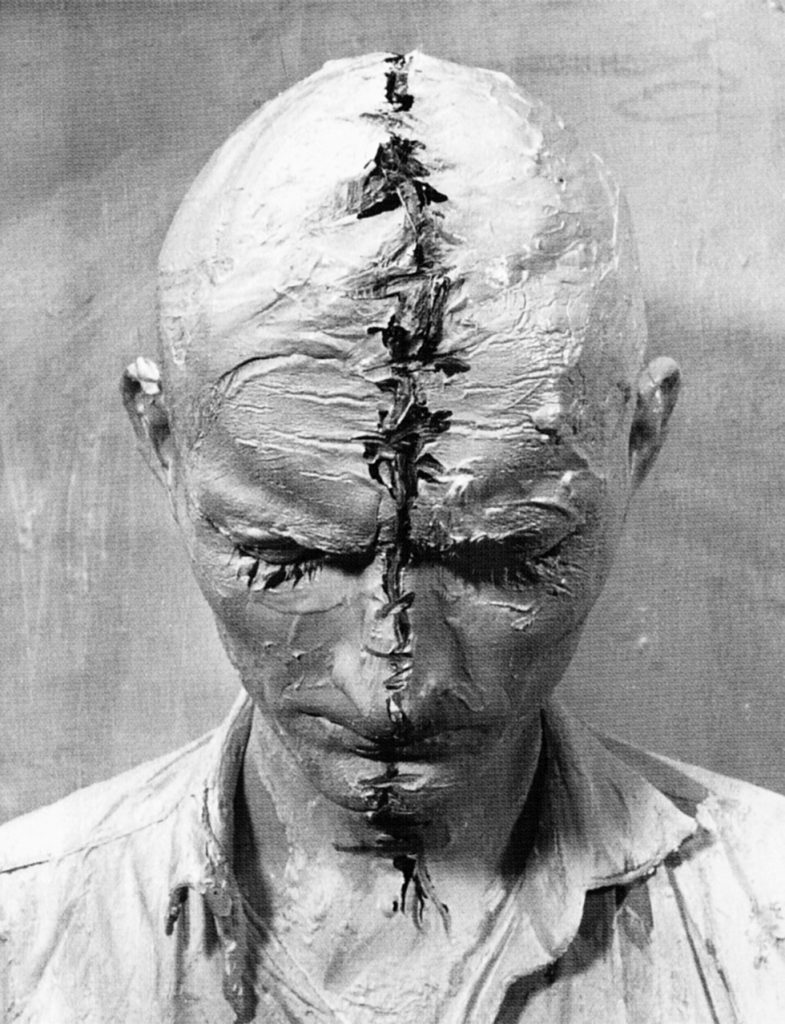

Vienna Walk or Wiener Spaziergang in German, was one of Günter Brus’s best-known actions and his first completely public performance. It consisted of the artist walking through the center of Vienna dressed as what he called a “living painting” with his body painted entirely white with crude black stitching dividing it and his suit into two halves lengthways. He transformed himself by becoming a living painting in a way that the violence and art started to fuse together.

It is particularly important to the history of performance art because the photographs that document the walk, taken by the artist’s friends and collaborators, have created such a strong myth around what really happened on the day, and are considered some of the first records of performance art to have become artworks in their own right.

Revealing the work to unsuspecting passers-by rather than to viewers who came intentionally to a gallery or performance space for a pre-advertised event also proved the Actionist ethic of liberating art from the traditional gallery or museum space, as well as forcing ordinary members of the Austrian public to come face-to-face with highly controversial art they might otherwise have made an effort to avoid. The work paved the way for future artists to perform to an unsuspecting public on the street.

At the time in socially-conservative Vienna, neither the general public nor the authorities were appreciative of these performances. Brus’ performative piece ended in run-ins with the police, including arrests and prison terms.

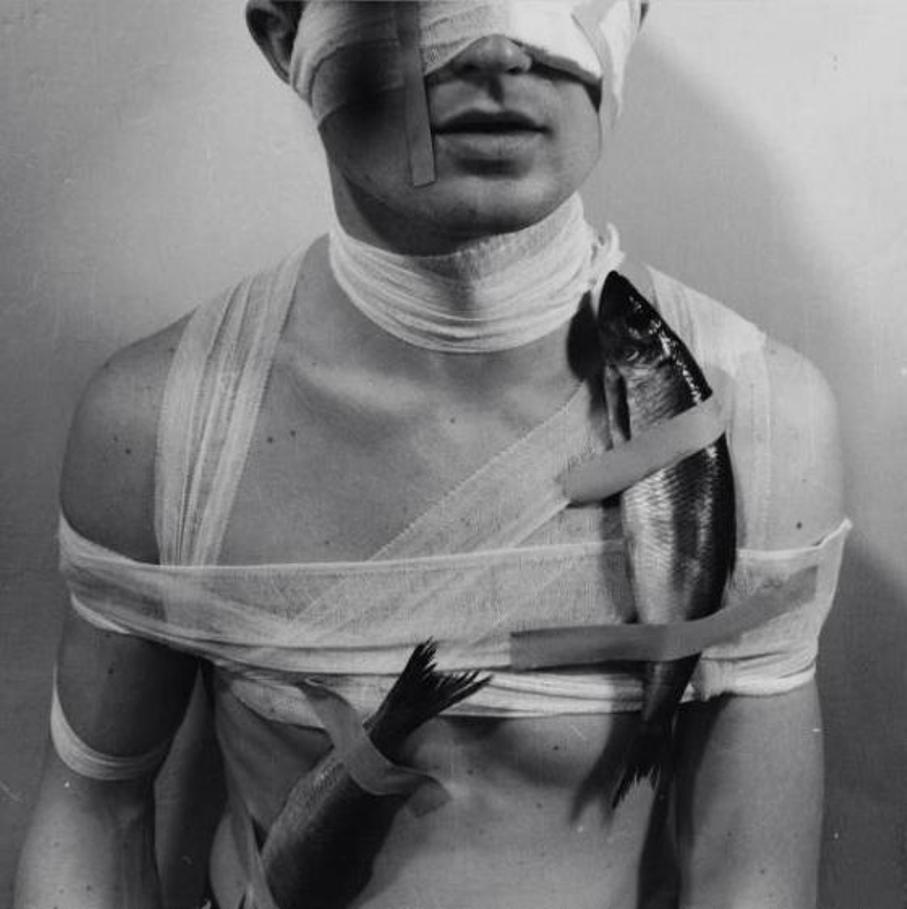

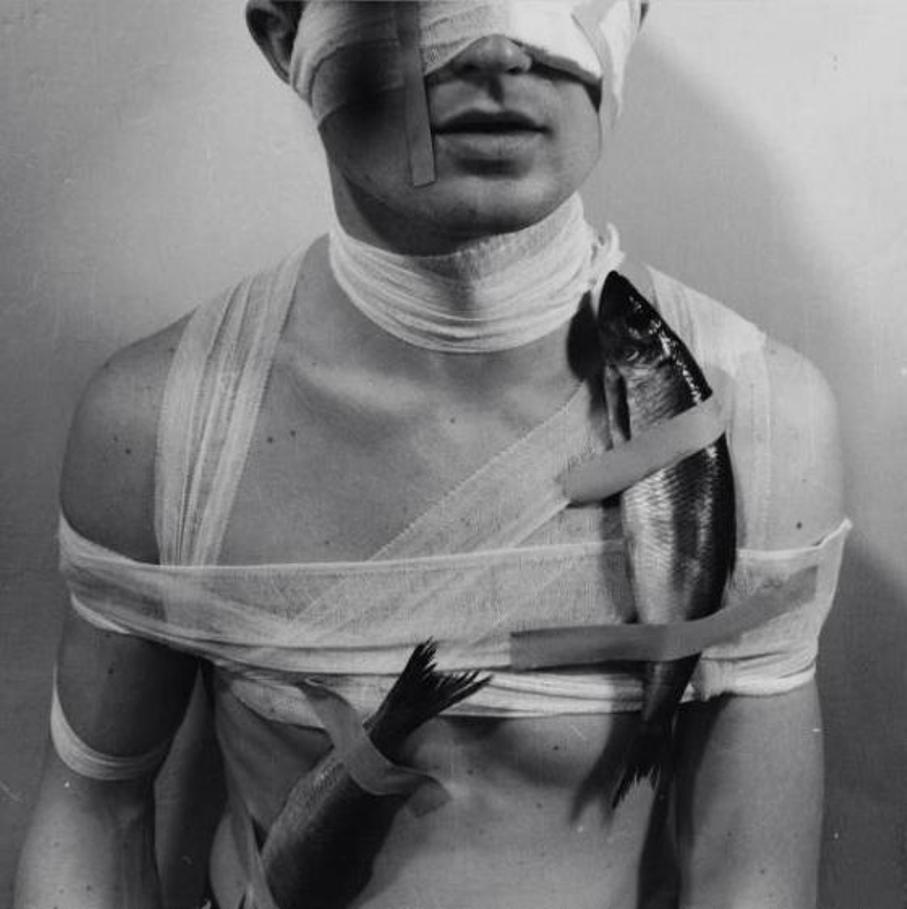

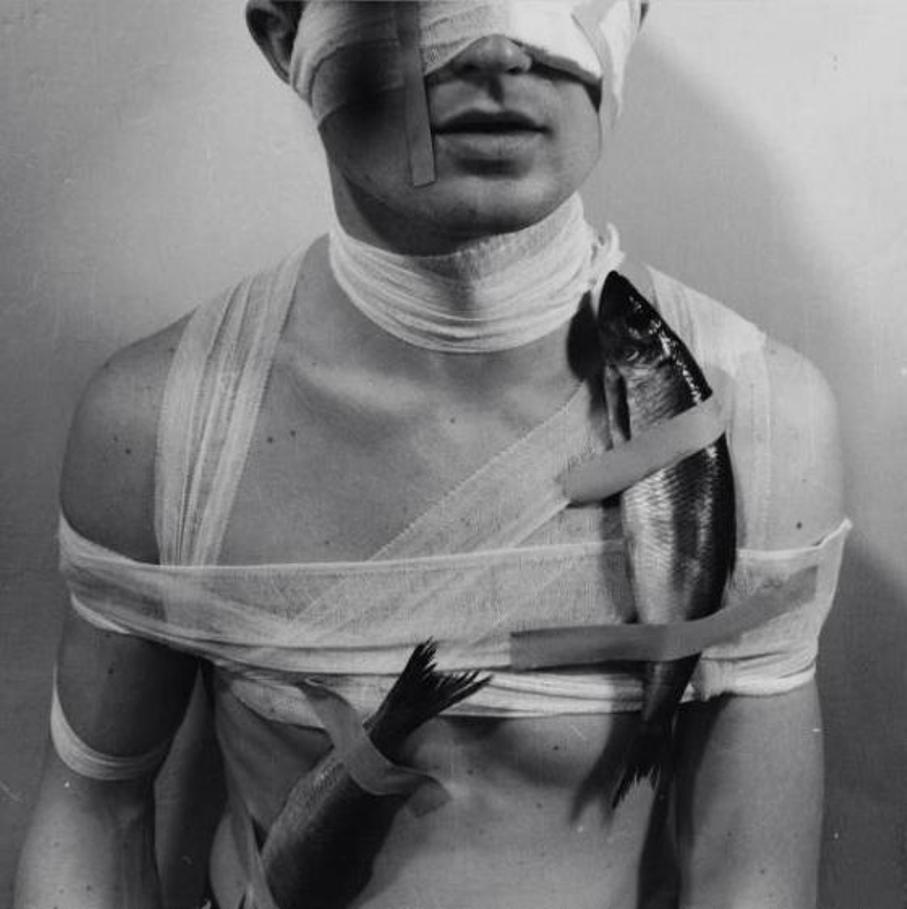

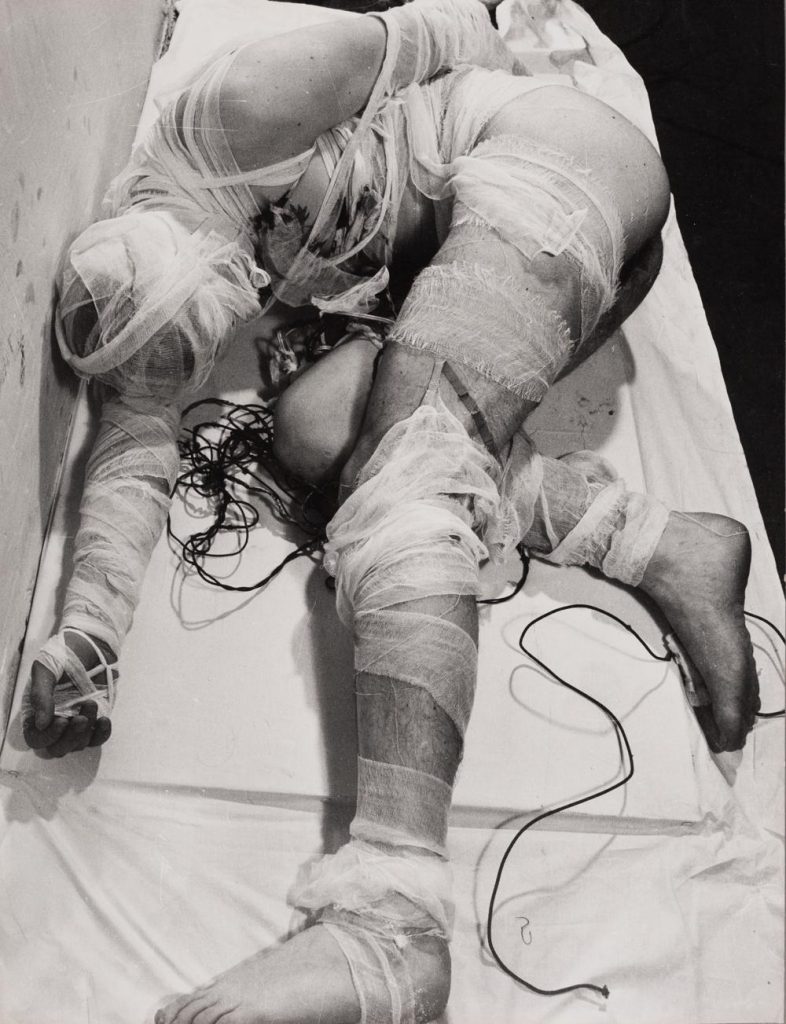

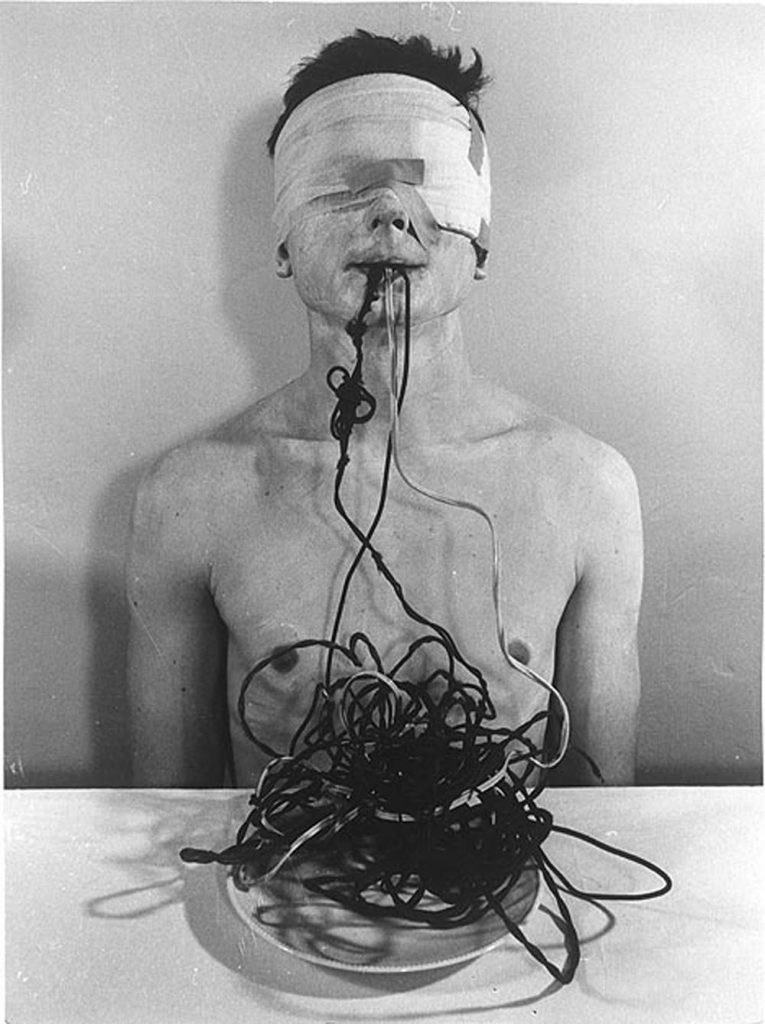

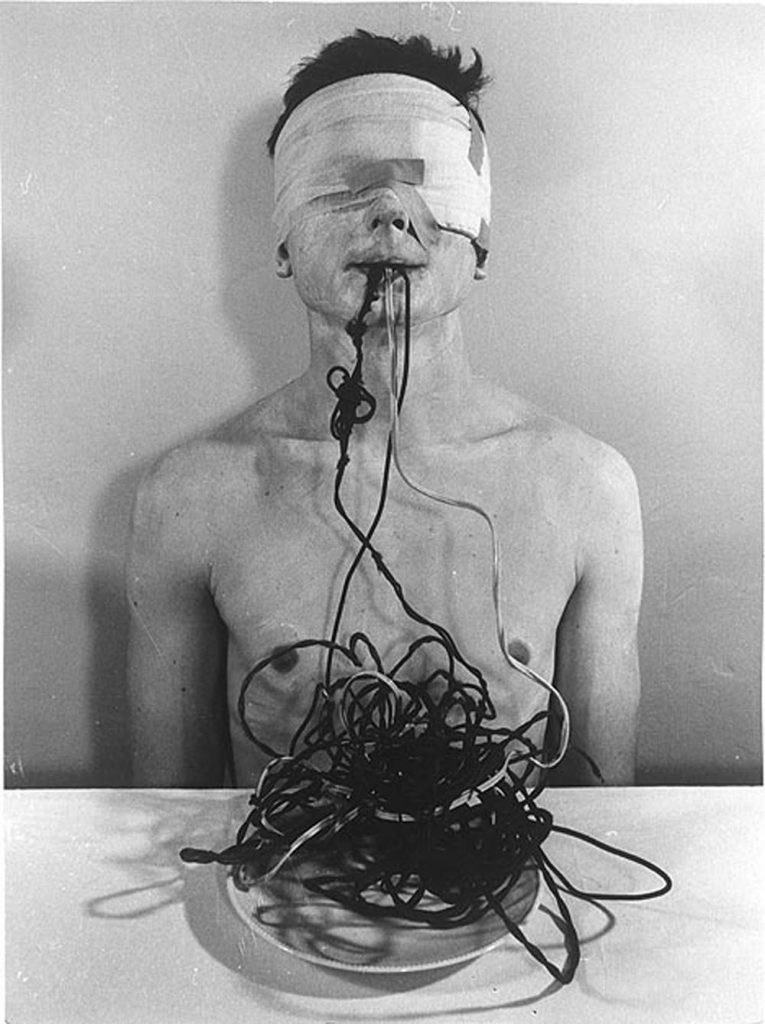

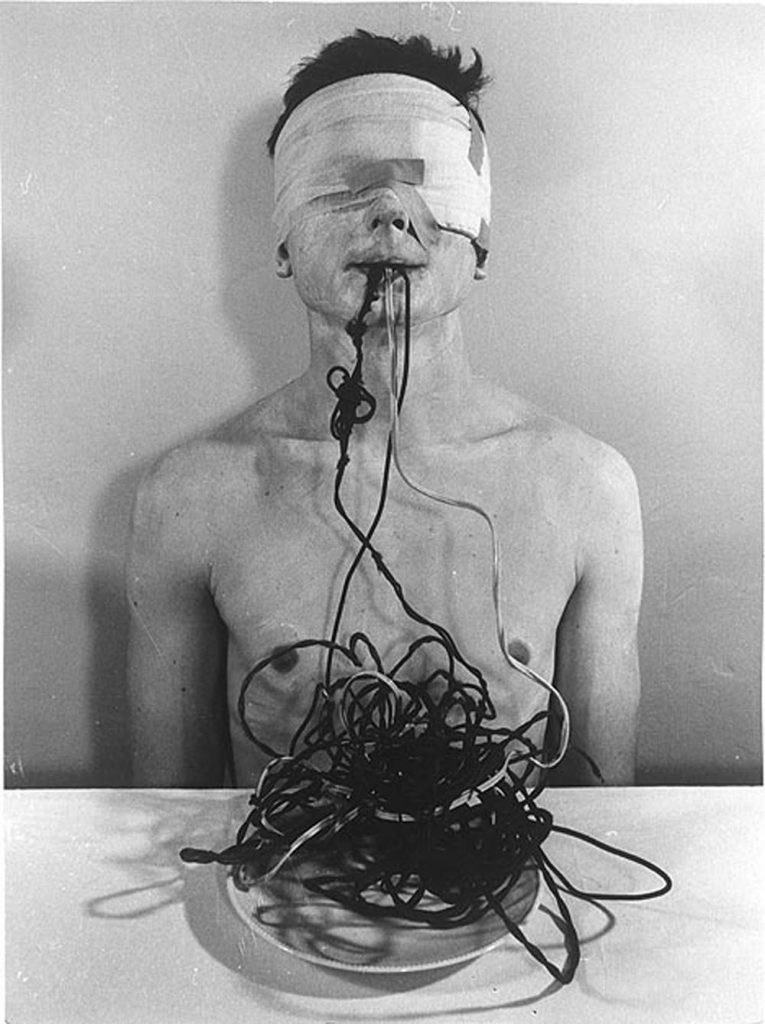

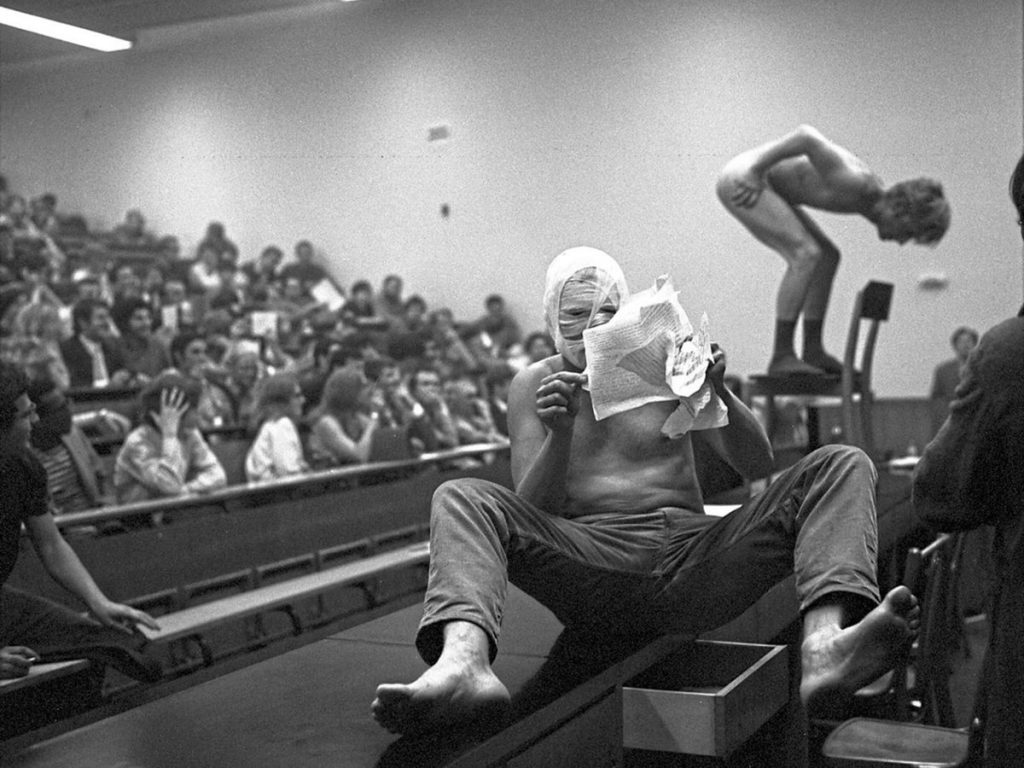

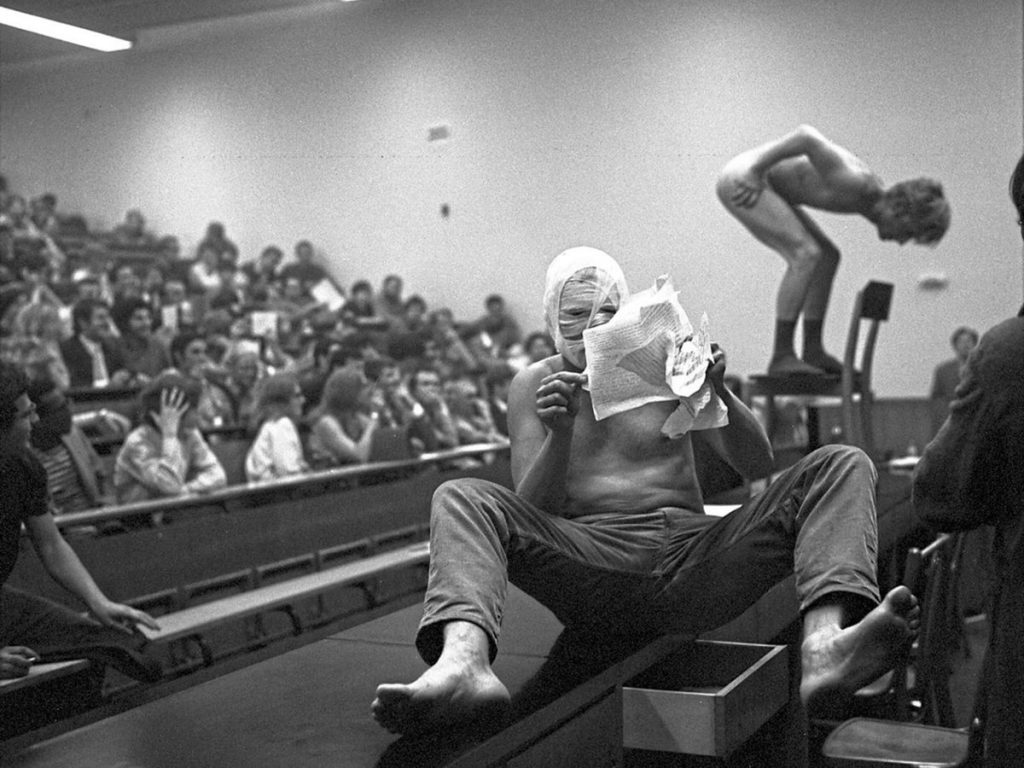

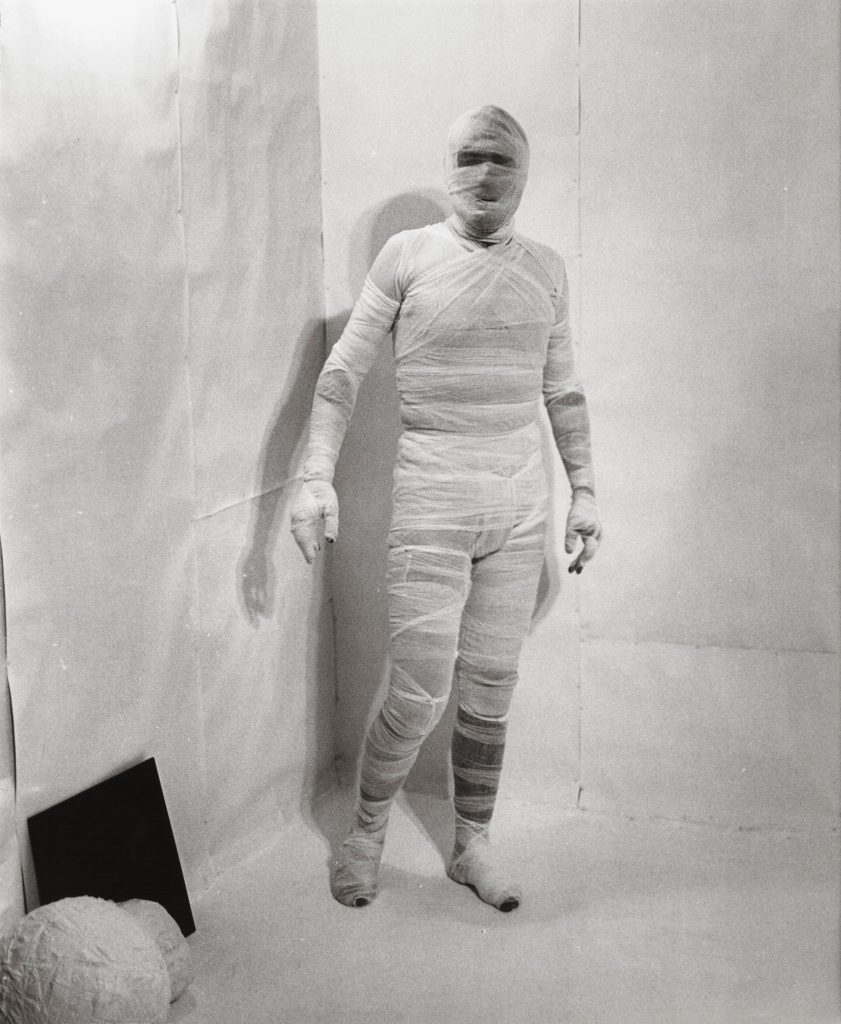

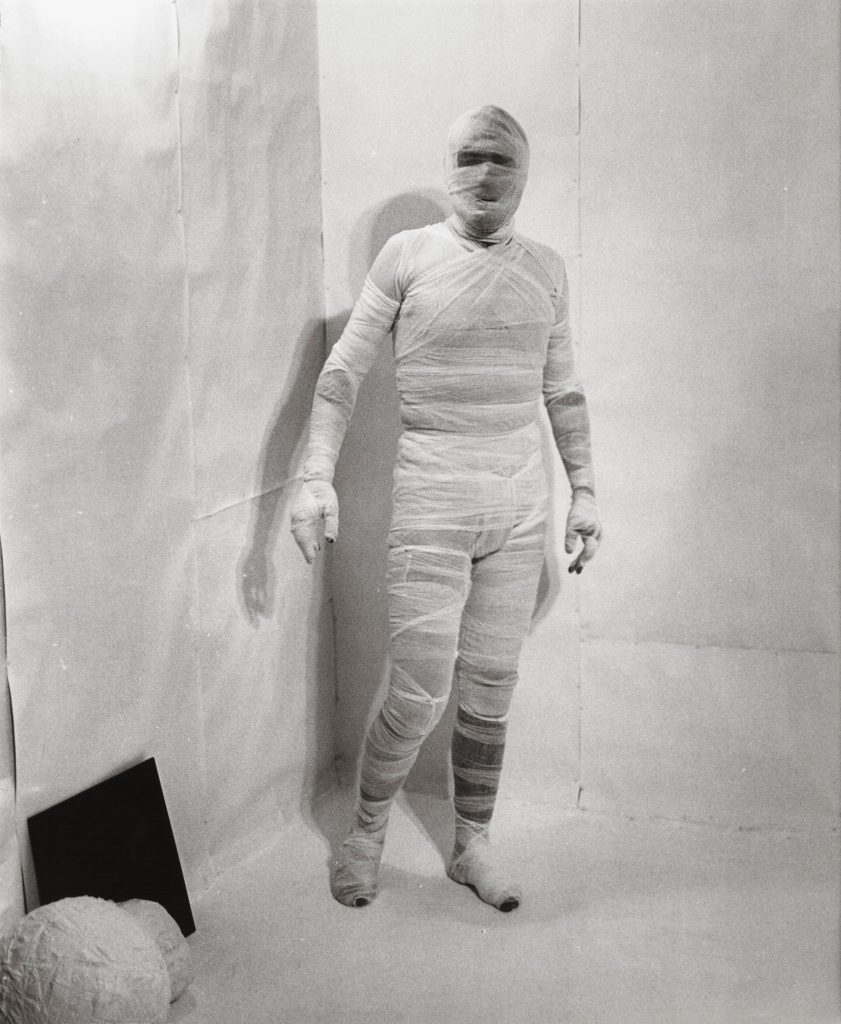

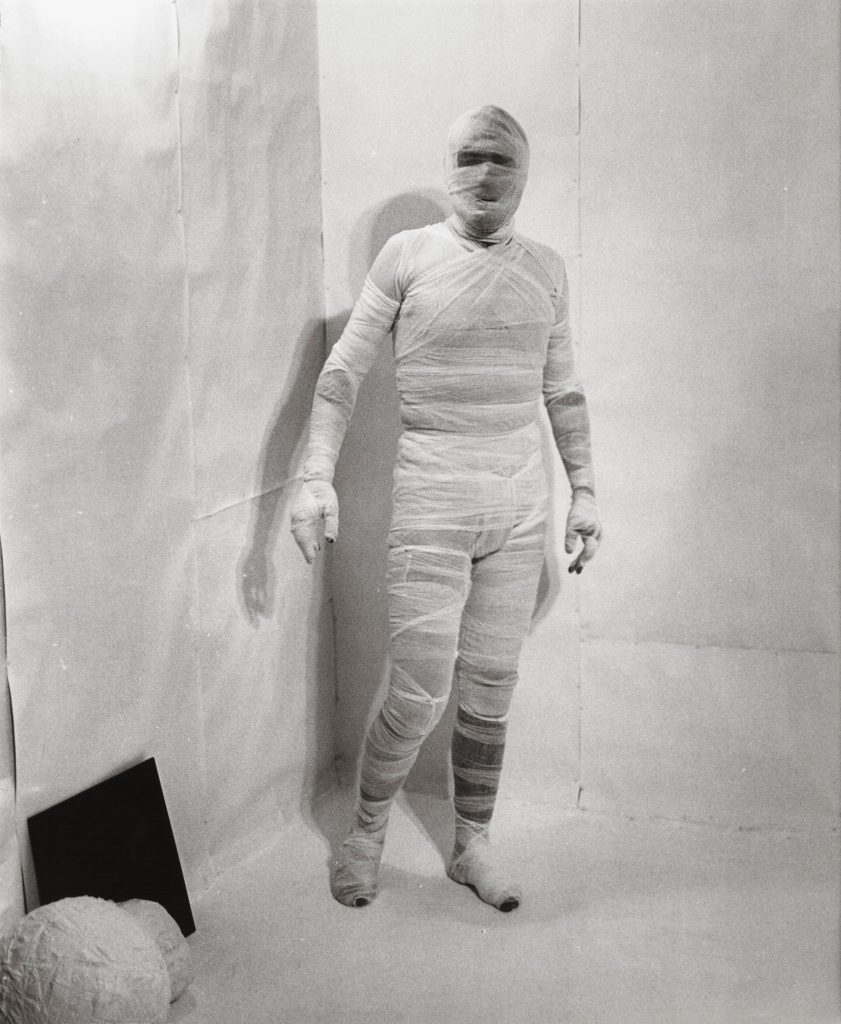

In the 68 images that make up Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s 3rd Action, the viewer sees a bandaged, possibly dead figure resembling Hans Bellmer‘s life-size dolls in highly contorted positions lying on a creased white sheet. To complete the disturbing scene, there are strong forms in the images such as white balls and rectangular mirrors that are very simple but have a huge aesthetic impact. The artist is also presenting us with an enigmatic depiction that involves both healing and pain: bandages look suffocating, fluids being injected look poisonous, and it seems the figure is being mutilated rather than treated.

Unlike the other Actionists, whose principal interest was in the experience of live performance, Schwarzkogler’s actions were all carefully staged purely for the camera, and he created just six of them before committing suicide in 1969. Schwarzkogler is the only artist of the four without a painting, drawing, collage, or sculpture on display. His work is manifested entirely in the form of documentary black and white and color photographs that explore various configurations of bodily abjection, simulated castration, bandages, and bondage often looking as cadaver-like tableaux or just a scene from a horror movie.

The castration theme in some of Schwarzkogler’s other work inspired a myth, that he had accidentally killed himself by cutting open his own genitals in a performance gone wrong, whereas he actually died by falling or jumping from his Vienna apartment. Of all six performances the artist made throughout his artistic career, the 3rd action is the most remembered one.

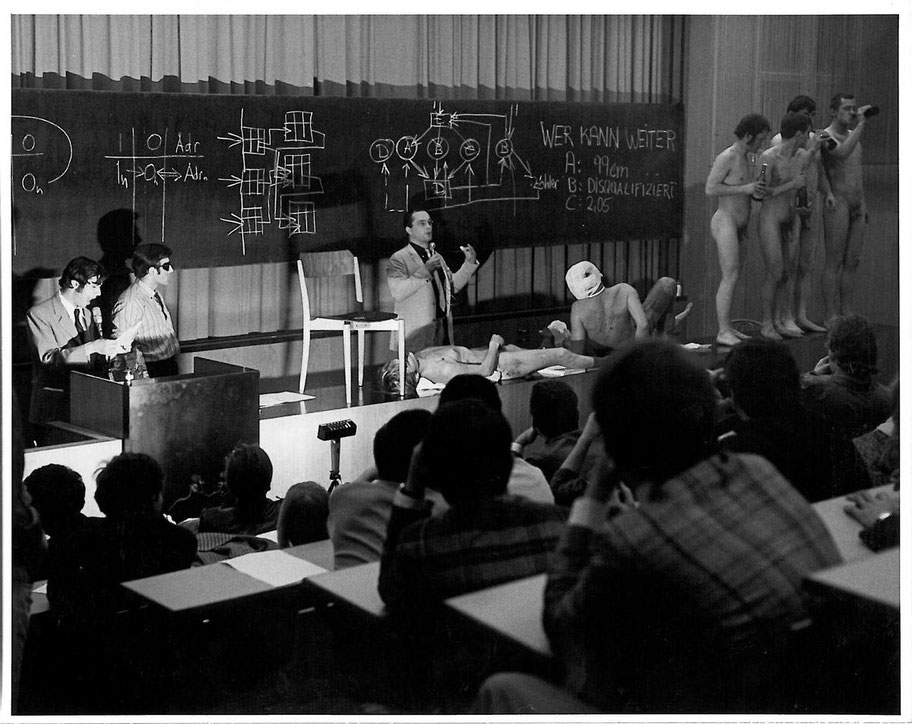

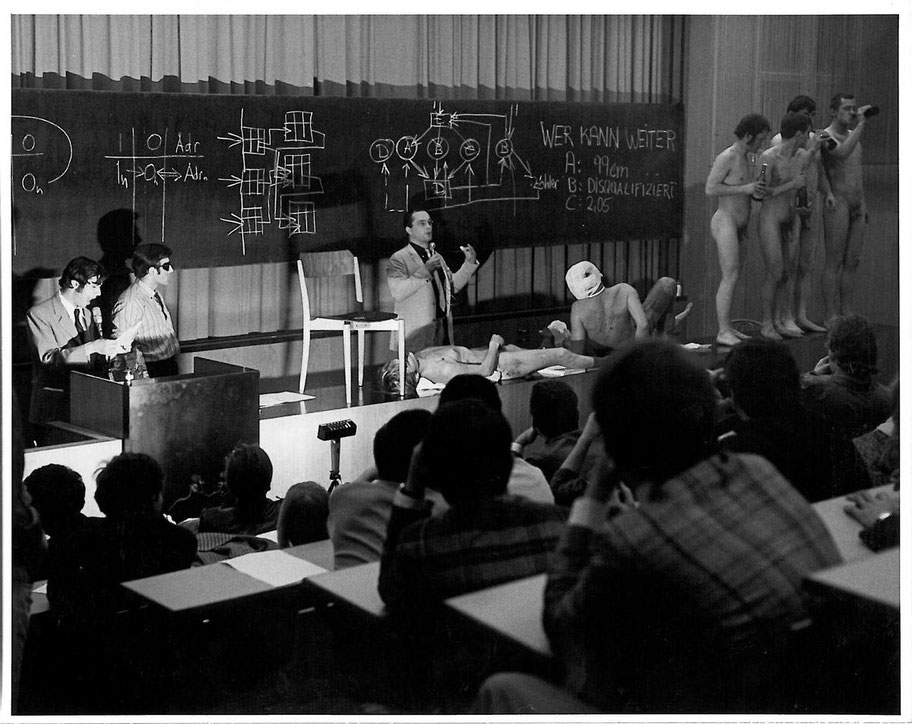

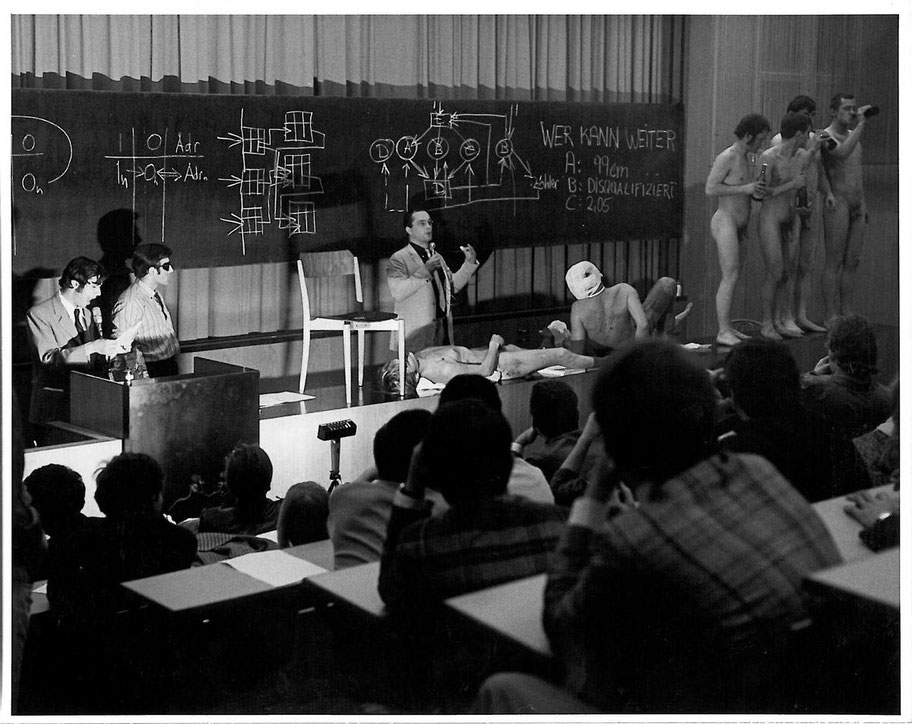

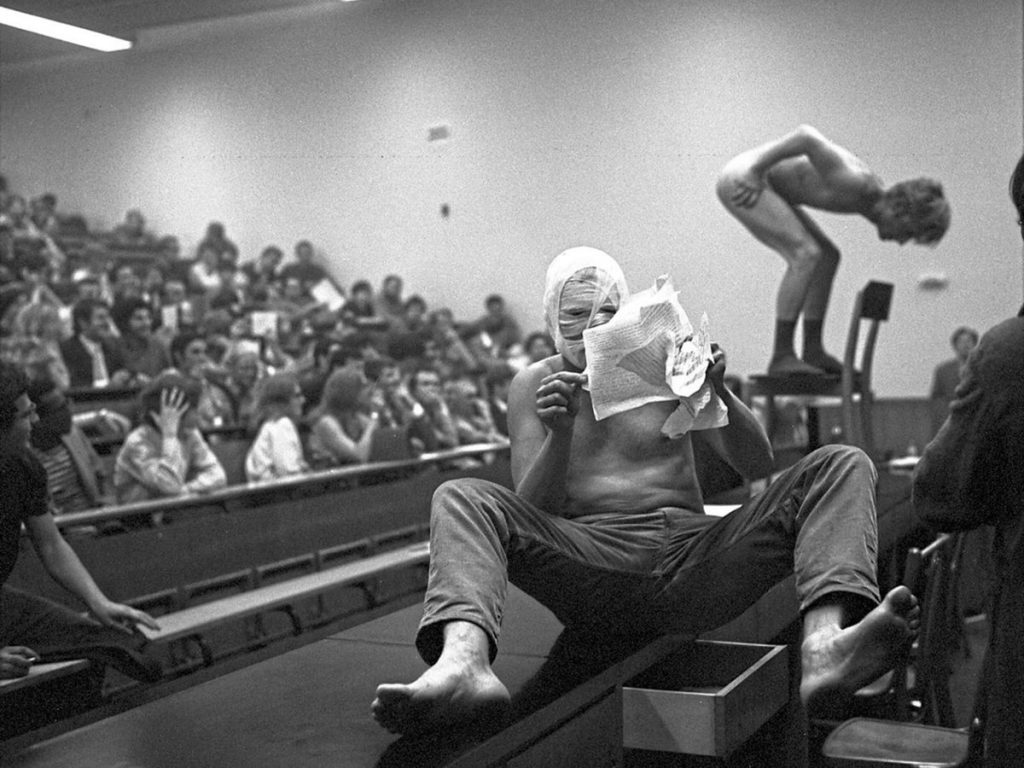

On the night of June 7th, 1968, Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, Peter Weibel, and Oswald Wiener staged a violent and multiple taboo-breaking takeovers of a student gathering at the University of Vienna which themselves denominated as Kunst und Revolution (Art and Revolution). The participants broke into a lecture hall before whipping and mutilating themselves, urinating, covering themselves in their own excrement, masturbating, and making themselves vomit—all while singing the Austrian national anthem.

The night is remembered by art historians as one of the most important of the Actionists’ joint works. By acting so outrageously and breaking the law so rebelliously, they summed up everything that they had been expressing in previous performances in one intense artistic event. It marked the beginning of the end of Viennese Actionism, as key members left Vienna to avoid prosecution.

Many Austrians still remember the event, called Uni-Ferkelei (University Obscenity) by their national press, with revulsion. A few photographs and a two-minute film are the only surviving pieces of documentation of the seminal evening.

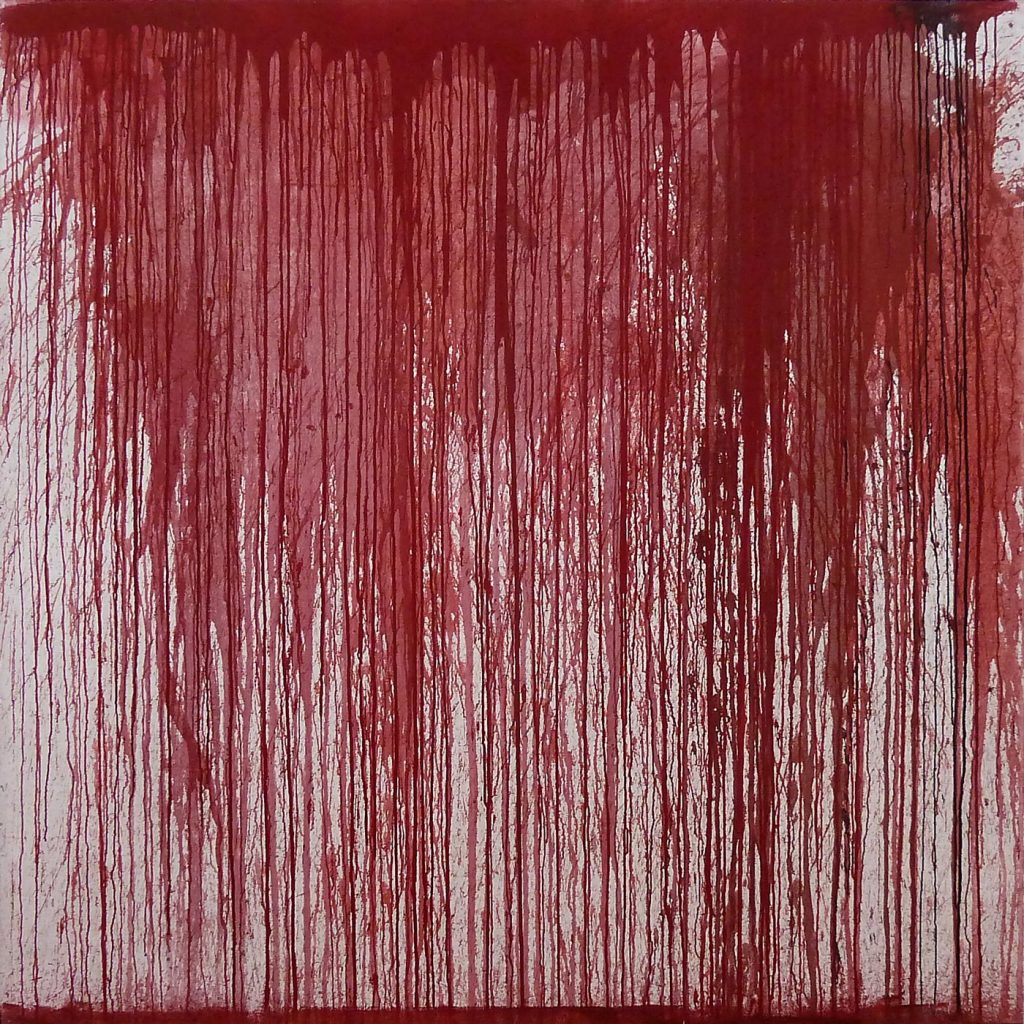

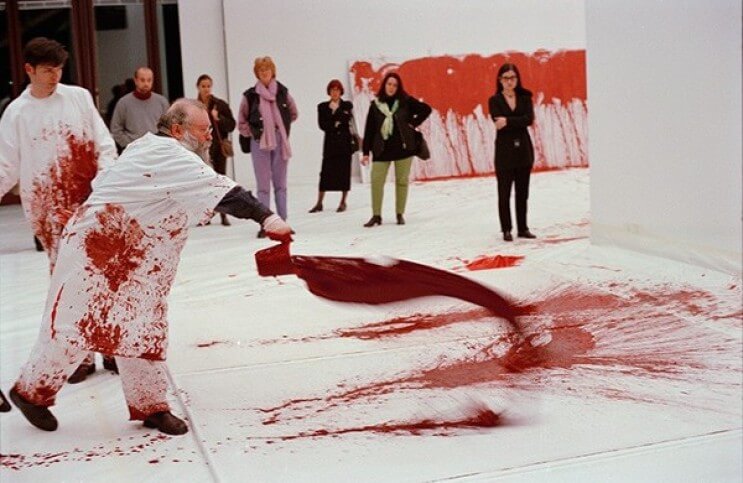

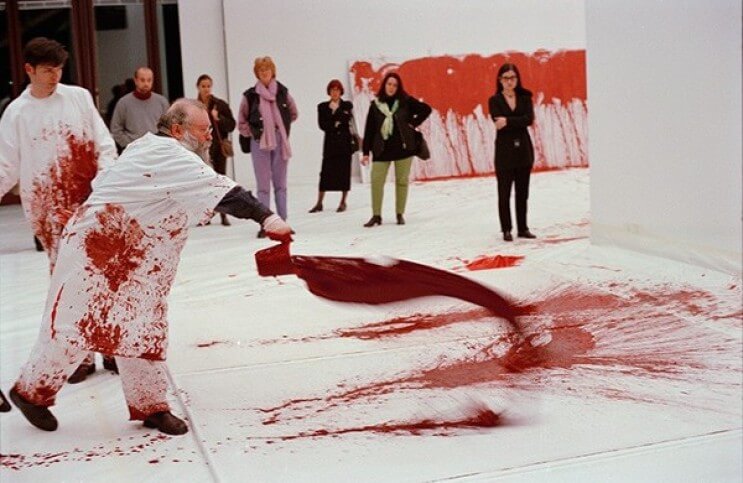

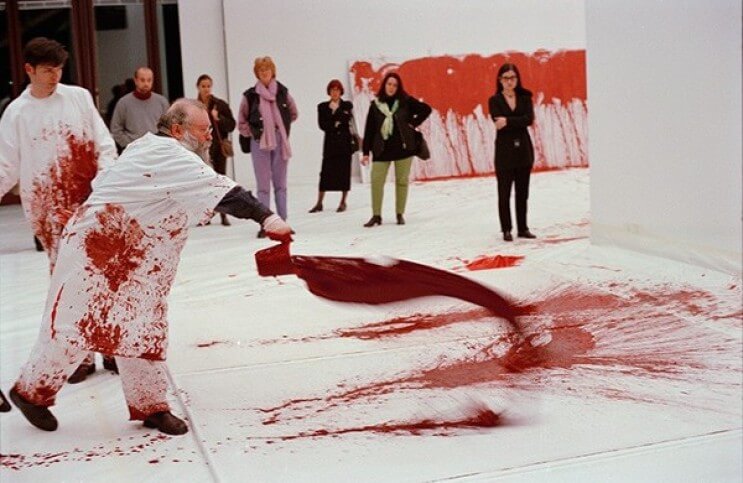

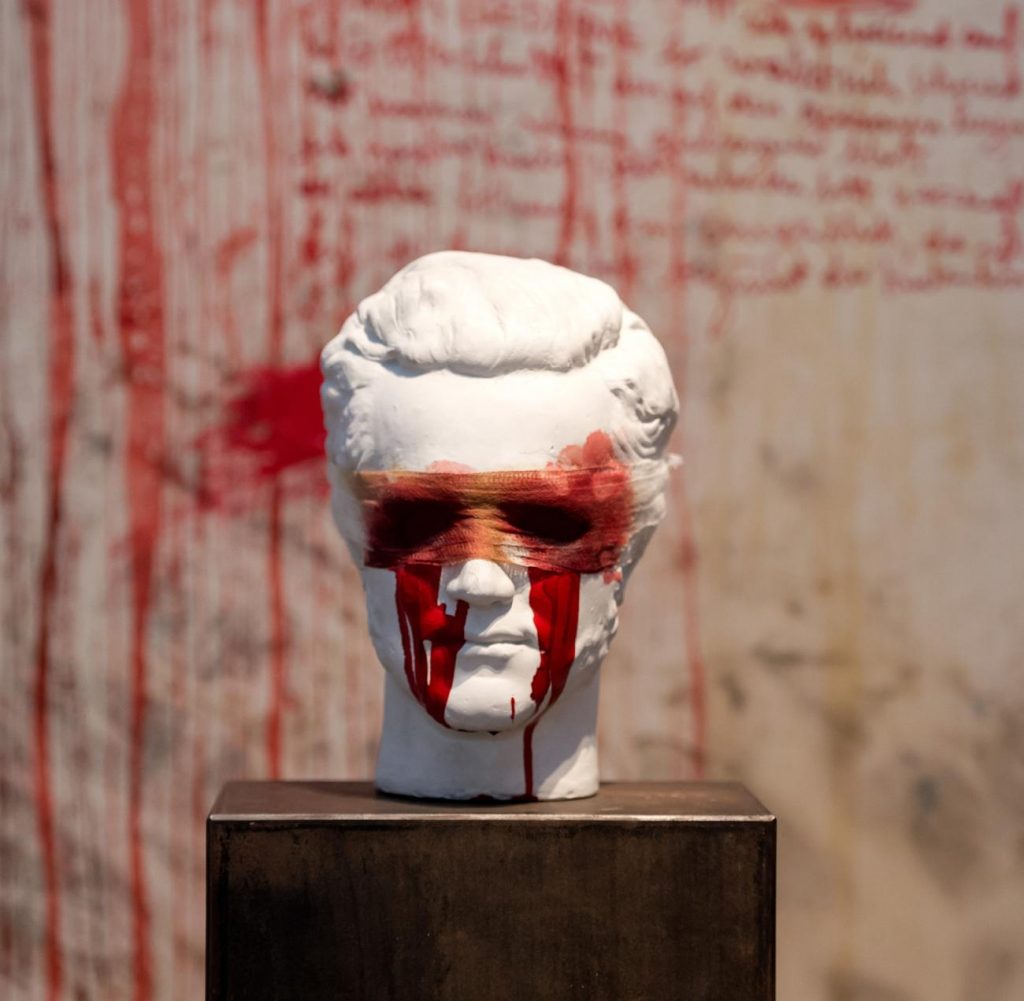

Poured Paintings are just one of a series of two-dimensional works Hermann Nitsch created alongside his graphic and often violent performances. It was made by throwing and pouring red paint directly onto a sacking material so that the final framed piece is reminiscent of the aftermath of a violent attack or bloody killing.

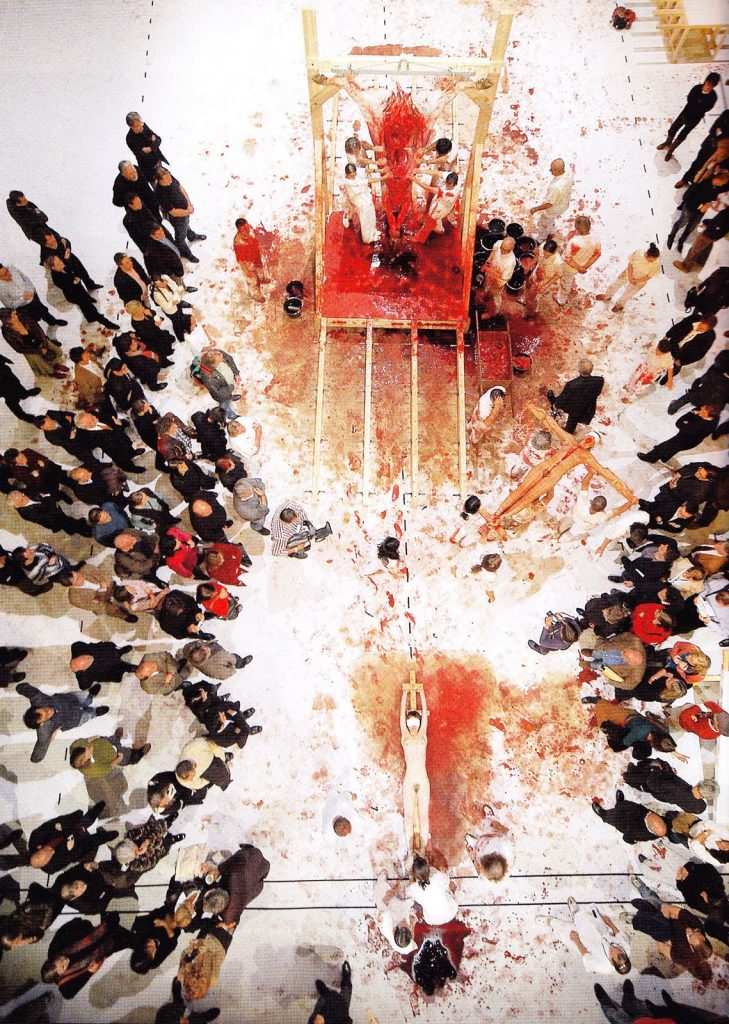

Before, during, and after the Actionist era, Nitsch in particular has continued to be inspired by the energy of action painting in every aspect of his practice. He employed its techniques in his own unique way by using blood, milk, entrails, and other organic materials in his paintings to evoke the same themes of ritual, sacrifice, and redemption that he tackled in his most known performances called Orgien Mysterien Theater.

Nitsch’s desire to use his art as a kind of catharsis, and to incorporate Christian symbols (crucifixion, communion) with pagan ones (drunken excess, the drinking of blood) have earned him a reputation as one of the most provocative and influential of all Actionists.

I never intended to provoke. I always looked for intensity. The intensity in historical art always fascinated me. The tragic plays of antiquity, the Passion of Christ…intense art always had my love. If one of my actions provoked the people at one point, well, so be it. But provocations were never cooked up at the drawing board.

Hermann Nitsch, interview at Vice Magazine, Jonas Vogt, Alexander Nussbaumer, 2010.

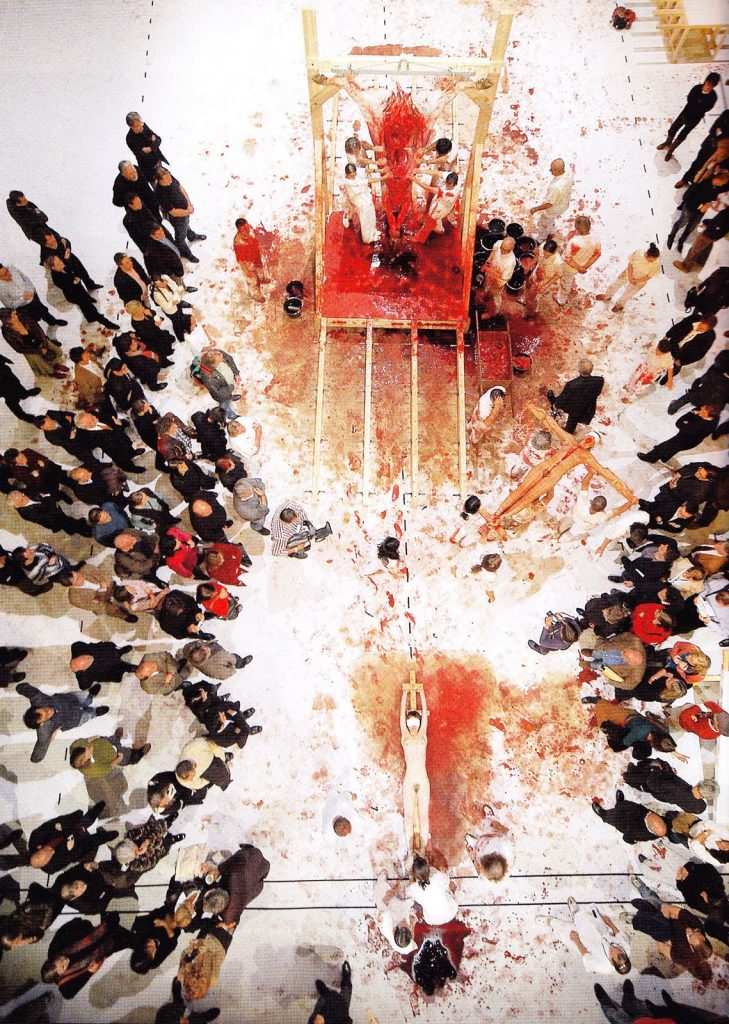

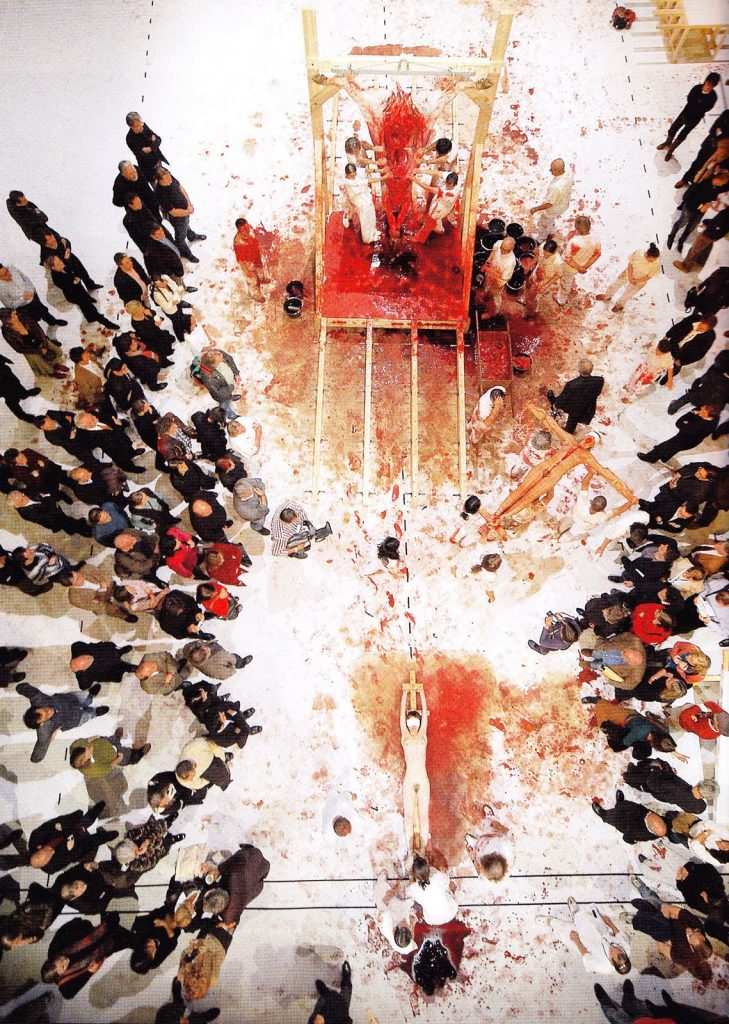

The centerpiece of Nitsch’s Orgies Mysteries Theater, which he has been working on since 1957, and which is considered a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) is a six-day play that has been performed at its full length only once. The carefully scripted work involves more than 100 set pieces involving processions evoking Dionysian rites, symbolic crucifixions, the slaughtering and disembowelment of dead animals, and painting on canvas and on bodies with their blood.

By the re-appropriation of the catholic rituals or imitation of the crucifixion and his crossing of them, Nitsch seemed to create a sort of ritual aspect to the whole work. But beyond the imagery of sacrifice, viscera, and a lot of blood as a primary medium for the creation of his actions, in every action can be seen a catharsis, similarly to Greek tragedies.

Marina Abramović, even though not being part of the Viennese Actionism movement, also took part as a performing artist in one of his actions. This experience inspired her to the point that in 1997 she introduced in Venice her installation Balkan Baroque with a pile of bloody cow bones forming a pyramid which she was washing during the whole performance. It was a reaction to the Bosnian war, because as she explained:

You can’t wash the blood from your hands as you can’t wash the shame from the war.

Marina Abramović on the Balkan Baroque, MoMA.

In early works by Brus, much of the violence was only implied. In this late work entitled Stress Test, Brus urinated into a vessel and drank, beginning a frenzied action, then slashed his own shaven skull with a knife. Art historians have argued that in subjecting his own body to such brutality, Brus is symbolically reclaiming the body tortured and killed by the Nazis and he is investigating the body’s tolerance for pain.

The performance, like others by the group, was meant to shock the Viennese bourgeois out of their complacency. This was Brus’s last action (one year before the official end of the group) when he realized that there were no further boundaries to push except with his own death.

Inspired by figures of the early 20th-century Austrian avant-garde, who had been active before the outbreak of World War I such as Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and the artists and designers of the Wiener Werkstätte and fed by radical opposition to bourgeois society, Viennese Actionism transgressed traditional boundaries to create aesthetic extremes and highly controversial performances centered on the bodies of artists and their models.

The body served not only as a canvas for Vienna Actionists. It also became a subject of close examination and analysis, as the artists delved into more deeply rooted taboos including sex, bodily affluence, and gender roles. For some artists, this analysis culminated in questioning the integrity of their bodies and expressing sovereignty over themselves.

In Brus’s last action, he subjected himself to self-mutilation bordering on suicide. Nitsch’s bloody performances and processions show the harsh reality of life and incomprehensible human actions when people believed in salvation through sacrifice. Marina Abramović reacted to the horrors of the Bosnian war (but to the war in general) with her Balkan Baroque installation and questioned standards of female and artistic beauty in Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975) by aggressively brushing her hair until it hurt.

Even though their actions might be considered by many controversial, despicable, and even disgusting, it is necessary to look for what purpose they created their works, what led them to do so, what they wanted to point out and warn about the society, and especially what the generation of young people who survived the terrors of the World War II had to endure.

Blood, the stench of one’s own urine and feces, rotten animals or their entrails, all of which in some way pointed to the war and how not only soldiers but also ordinary people encountered this on a daily basis. Something that was almost normal for them and at the same time natural and human. Something for which one must not hide or close his eyes and forget, but on the contrary, one should look directly at the events that have happened in human history and which humanity must no allow to happen anymore.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!