Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

Rembrandt is less known for his mythological paintings, but their visual impact matches any of his religious images and secular portraits. The Abduction of Ganymede showcases an ancient Greek myth through Rembrandt’s lens.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669) was the leading Dutch painter of his generation. The Dutch Golden Age, a period of great creative output, is simply unimaginable without Rembrandt’s presence. He had a flourishing career based in Amsterdam, where he received and influenced many visiting contemporary artists. His portrait paintings and religious scenes were, and still are, cornerstones to his artistic reputation as a master painter. However, his mythological images are equally as masterful. One of his mythological masterpieces is the Abduction of Ganymede, now housed in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait Wearing a Feathered Bonnet, 1635, Buckland Abbey, Yelverton, UK.

Abduction of Ganymede is an oil on canvas with a portrait orientation measuring 177 centimeters high and 129 centimeters wide. Rembrandt painted Abduction of Ganymede in 1635 when he was only 29 years old. His youthful confidence injects the painting with a discerning maturity that foreshadows his later years. The painting depicts a violent scene of a large brown eagle grabbing a small pale boy. The little child screams and cries in terror as he is whisked off the ground. He urinates in absolute fear. It is an ugly kidnapping.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

The bizarre subject is depicting a scene from ancient Greek mythology: the myth of how Ganymede joined the Greek gods as a cupbearer. Ancient Greek religion was a polytheistic faith that had countless gods, goddesses, nymphs, demigods, and heroes. Ruling over this large religious body were twelve great gods who lived on Mount Olympus. Zeus was the king of the gods, and he held daily dinners for his divine court. He and his eleven diners would eat ambrosia and drink nectar served by minor deities and beings.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

Hebe, the goddess of youth and forgiveness, was the personal attendant of Zeus. Every day she served Zeus his daily meals until one eventful day she was dismissed from her post. Depending on the classical source, Hebe either enraged Zeus by tripping and spilling food and drink all over him, or by marrying the hero Herakles (Hercules). Clumsy waitress or married lady; whatever the reason, her position was empty. Zeus, not accustomed to serving himself, quickly wanted a replacement!

Zeus had a wandering eye that easily lusted for anyone young and beautiful. Soon after Hebe’s vacancy, Zeus noticed Ganymede, who was an extremely handsome Trojan prince. Ganymede descended from an illustrious line- he was the son of Tros, the founder of Troy, and he was the grandson of the Trojan river gods, Simoeis and Scamander. His good looks and pedigree made him the perfect candidate for a new cupbearer on Mount Olympus. However, there was an impediment. Ganymede was completely unaware of his impending situation.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

Zeus did not believe in mutual consent. If his sexual overtures were not well-received, then he sexually conquered through deceit, kidnapping, and rape. If Zeus was a contemporary mortal, he would have been labeled a sexual predator with a long criminal history of sexual offenses. Ganymede was soon to be the next victim of Zeus’s sexual rampage.

Ganymede was minding his own business when suddenly a large eagle (a transformed Zeus or sent by Zeus) appeared in the sky. It descended in fury and seized Ganymede with its talons. Before Ganymede could resist the bird, he was flown up towards Mount Olympus where he met Zeus.

Ancient Greek and Roman poets insisted on and emphasized the homoerotic desires of Zeus; to them, Ganymede became Zeus’s lover and cupbearer. Later Renaissance writers rejected this homoerotica and reinterpreted it as a moralistic tale of the innocent soul lifted upwards to the heavens towards its divine creator. Regardless of the Classical or Christian interpretation, the end result was the same: Ganymede was later rewarded for his services by being immortalized as the constellation Aquarius near Aquila the Eagle.

Rembrandt and the majority of Baroque painters were well-educated in ancient classical mythology, so his use of the story of Ganymede in one of his paintings is not unusual or bizarre. However, Rembrandt’s visual interpretation of the story is not based in classical authority; it is based upon his creative inclinations to heighten the drama of the event. Most people relate to beauty with ease and openness. However, most are repulsed when confronted with ugliness. Rembrandt injects deep elements of ugliness into the Abduction of Ganymede to the point of causing revulsion in his audience.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

To begin with, the most obvious difference between this classical myth and this Baroque painting is the age of Ganymede. The prince of Troy is not a strong, sexy adult- he is a weak, unsexual child. Rembrandt transforms Zeus, the sexual predator, from the predator of adults to the predator of children, rendering him a pedophile- a status with almost universal revulsion and rejection. Social sexual norms are transgressed to repulse the viewer.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

Bodily functions are a squeamish subject for most people, and viewing and handling human waste are not traditionally considered pleasures by modern society. Therefore, Rembrandt’s urinating Ganymede does not spark feelings of attraction. The little boy is so scared that he is literally wetting himself; he does not know what is happening to him. He cries, screams, and urinates. Anyone with kindness can feel sympathy towards him. Rembrandt achieved such realism by observing and sketching crying children in his Amsterdam neighborhood. What a noisy preparation for the painting!

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

While Rembrandt broke away from many traditions of classical mythological painting, he enhanced the genre with his psychological insights. Through less dramatic chiaroscuro but more naturalistic details, Rembrandt was able to create a psychology of light. The psyche and personality of his subjects rise from within to express the complexity and energy of the human interior. Ganymede is conscious of his situation and the perils for his body and soul. The light ripples across his contorted face and flailing body. The stillness and contemplation of Rembrandt’s religious scenes are rejected for the motion and reaction of a mythological scene. The human condition is expressed through illuminated intricacy.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

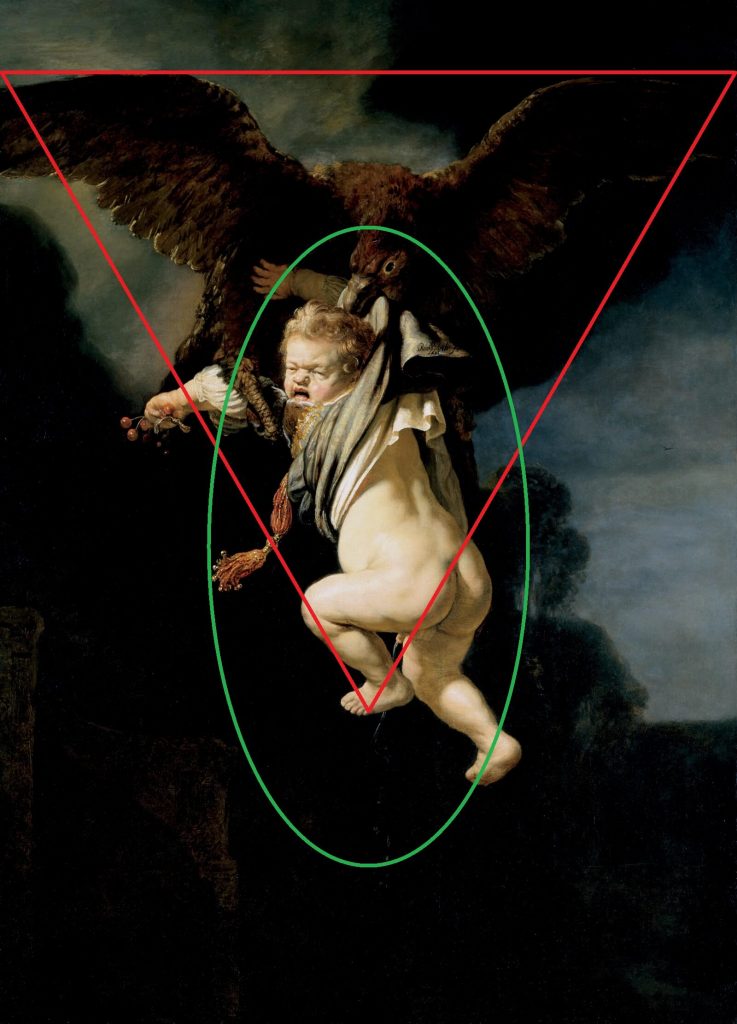

Mathematics is not just for the worlds of science, industry, and business; it plays a major role in the Western art tradition too. Rembrandt was no exception. Many of his paintings have hidden geometry including Abduction of Ganymede, which has an equilateral triangle and an ellipse.

Geometric Overlays: Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

The outspread wings of the eagle form the upper edge of an equilateral triangle, highlighted in red. This triangle measures 129 cm (50.8 in) wide, the canvas’s width, with a height of 111.7 cm (44 in). The triangle enframes the eagle’s body, most of Ganymede’s body, and peaks at Ganymede’s left foot. The inverted triangle adds stability to the painting’s upper portion but adds dynamic energy towards the lower middle section. Stability and energy push and pull to add visual interest.

Below the equilateral triangle is an ellipse, highlighted in green. It has the same height of the equilateral triangle of 111.7 centimeters. The ellipse has a perfect 2:1 proportion as its width of 55.85 centimeters is one-half of its height. Its shape enframes Ganymede’s body and touches the boundaries of Ganymede’s right foot, Ganymede’s left tassel, and the eagle’s head. The implied ellipse adds stability to the center of the painting. However, its curving edges contrast with the triangle’s linear edges adding some geometric contradiction and visual interest.

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

Rembrandt was a master painter, and his Abduction of Ganymede is a masterpiece. It breaks almost all of the traditional rules of mythological painting up until Rembrandt’s generation. The god Zeus is not a moral beautiful divinity, but a depraved hideous monster. However, Rembrandt elevates his deviant subject through illuminated psychology and implied geometry. He teases the viewer with compositional stability, bulging energy, and visual contradictions. While the painting is not traditionally beautiful, it is beautiful in its intellectual and visual complexity. It is different, challenging, and even shocking, but not ugly. However, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. What did Rembrandt think when he beheld this painting?

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany. Detail.

Abduction of Ganymede, Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden Online Collection. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

Wendy Beckett and Patricia Wright, Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces, London, UK: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Self-Portrait, National Trust Collections. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!