5 American Painters Who Defined the Pirate Mythos

For many of us, the word “pirate” evokes images of an era full of gallant white-sailed ships, skull and crossbones flags, red bandanas, gold...

Theodore Carter 4 December 2025

2 February 2026 min Read

William H. Johnson’s paintings show a breadth of styles ranging from realism to Post-Impressionism, and later a folk art aesthetic that would become the hallmark of his most recognizable works. A product of the Great Migration, an expatriate married to a Danish woman, and a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, Johnson’s life spanned several major moments in 20th-century American history and intersected with several important international art movements.

Johnson was well-read, a student of folk traditions, and attentive to the work of other artists. The 10 paintings below showcase his sprawling artistic reach within 22 active years as an artist.

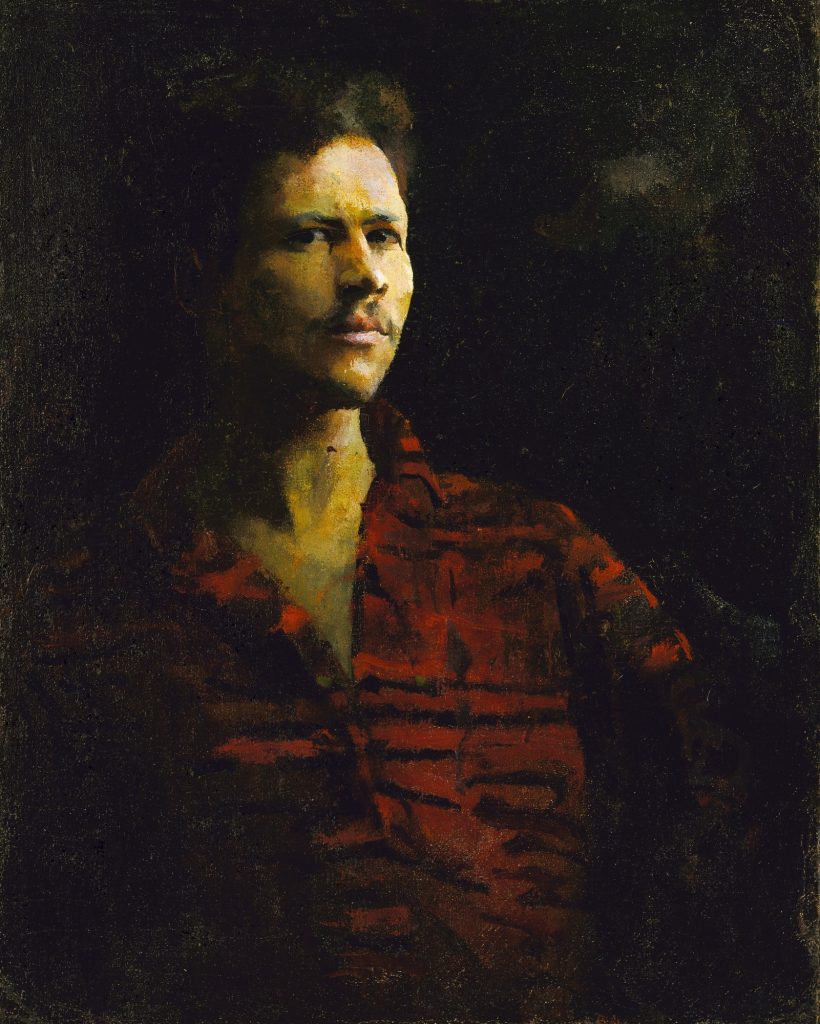

William H. Johnson, Self-Portrait, ca. 1923–1926, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Born in 1901, Johnson grew up in Florence, South Carolina, where he enjoyed drawing and copying cartoons out of newspapers. At the age of 17, he moved to New York and enrolled in the National Academy of Design, thinking he might pursue a career in cartooning. He received classical training in painting, and his early works show a grounding in realism.

William H. Johnson, Still Life, 1923. Artchive.

This painting showcases Johnson’s extraordinary talent and is reflective of the instruction he received at the National Academy of Design. Johnson grew close with Charles W. Hawthorne, an instructor who also ran the Cape Cod School of Art. In the summers, between 1924 and 1926, Johnson worked as a handyman at the Cape Cod School and studied under Hawthorne.

William H. Johnson, Village Houses, Cagnes-sur-Mer, ca. 1928–1929, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Despite Johnson’s talent, he failed to win the National Academy of Design’s most prestigious award in 1926, which would have come with a travel scholarship and continued training abroad. Instead, the prize went to a white student, Umberto Romano. Seeing this as an injustice, Hawthorne scraped together money on Johnson’s behalf. Johnson also earned extra money working in the studio of Ashcan School artist George Luks, from whom he also received instruction. With their help, Johnson traveled to Cagnes-sur-Mer in southern France.

William H. Johnson, Self-Portrait, 1929, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Like other Black American expatriate artists during this period, including Augusta Savage, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Archibald Motley Jr., Johnson enjoyed more freedoms in France than in Jim Crow-era United States. When in Europe, Johnson’s paintings started to depart from his training in realism and to reflect the rising tide of Post-Impressionism and Expressionism. However, meeting Danish artist Holcha Krake, whom he would later marry, had a profound impact on his art and the trajectory of his life.

William H. Johnson, Danish Roadside, 1930, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Johnson returned to New York in 1929 and, with encouragement from George Luks, applied for the Harmon Foundation’s Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes in the Fine Arts Field. He won the prize, and the Harmon Foundation took several of his paintings on tour in the early 1930s. Johnson also returned to his native Florence, South Carolina, and held a show in the local YMCA, where his mother worked as a cook.

William H. Johnson, Sun Setting, Denmark, ca. 1930, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Returning to Europe, Johnson reunited with Holcha Krake, and they were married in 1930. The interracial relationship would have been illegal in most of the United States, including Johnson’s home state of South Carolina. In Denmark, however, Johnson was well-received by Krake’s family and was free of the U.S. racial caste system. The two settled in Kerteminde, and the people and scenery of the harbor town became a major focus in Johnson’s work.

William H. Johnson, Willie and Holcha, ca. 1935, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Krake’s interest in folk traditions and mythology had a significant impact on Johnson, and increasingly, he grew interested in “primitivism,” or a return to folk art traditions. Johnson was a great admirer of Edvard Munch and the Expressionists. Chaïm Soutine and Paul Gauguin were major influences as well. Also, at this time, Picasso’s Cubism, borrowing heavily from traditional African art, was changing the European art world.

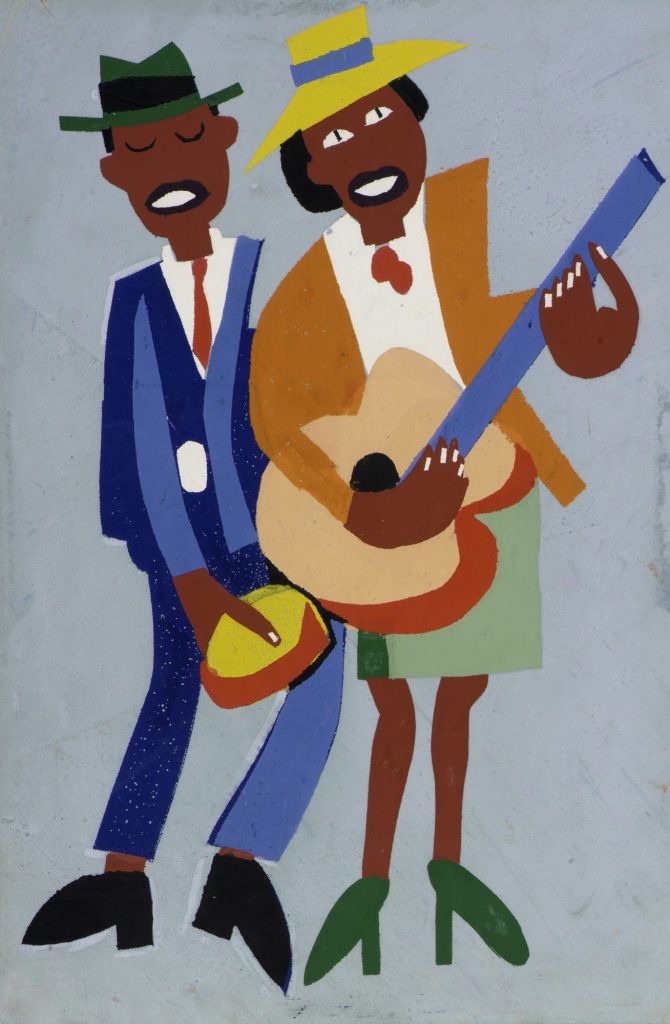

William H. Johnson, Blind Singer, ca. 1939–1940, Gift of Mrs. Douglas E. Younger, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

With the rise of the Nazis in Europe, Johnson and Krake returned to the United States. Though they preferred the kind of quiet, countryside existence they’d enjoyed in Kerteminde, returning to Johnson’s native South Carolina would not have been a safe place for the interracial couple. They moved to New York City, where Johnson became part of the vibrant art scene of the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson continued to develop his new “primitive” style and became interested in what he called “peoplescapes,” recording the vibrant lives of those around him in the city. In this screenprint, Johnson flattens shapes and uses deep, contrasting colors.

William H. Johnson, Farm Couple at Work, ca. 1942–1944, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Johnson’s work became increasingly narrative. It told the stories of Black soldiers during World War II, mine workers, and the movement of Black people from the South to the North as part of the Great Migration. He began his Fighters for Freedom paintings depicting American heroes like George Washington, Harriet Tubman, and Marian Anderson.

William H. Johnson, Three Great Abolitionists: A. Lincoln, F. Douglass, J. Brown, ca. 1945, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Washington, Smithsonian American Art Museum, DC, USA.

In 1944, Holcha Krake died of breast cancer. Shortly afterward, Johnson returned to Denmark to be with her family, but suffered a mental breakdown due to advanced syphilis. He was picked up for vagrancy in Oslo and sent back to New York. He spent the rest of his life in Central Islip State Hospital until his death in 1970.

Johnson’s artwork was then caught in a legal limbo as the state sought to extricate itself from responsibility for the work without significant consideration for family claims. The Harmon Foundation took control of much of Johnson’s work and donated over 1,000 pieces to the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. This undoubtedly saved much of Johnson’s work and preserved his legacy. However, the rightful ownership of Johnson’s paintings has been the subject of dispute.

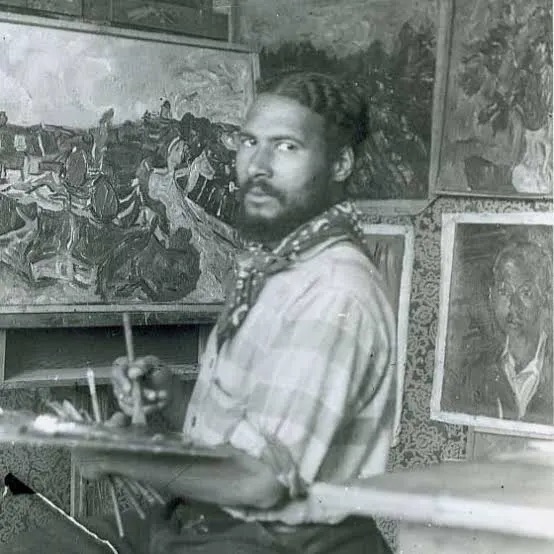

William H. Johnson at work. Everett Collection.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum showcased Johnson’s Fighters for Freedom series in a 2024 traveling exhibit. Clearly, despite a relatively short artistic career, Johnson’s vast output and varying styles contributed significantly to 20th-century American Art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!