Anna Ancher in 10 Paintings: Capturing Light

Anna Ancher, a local born and bred, became one of the leading artists of the Danish town of Skagen. She knew and painted her family, the inhabitants,...

Catriona Miller 29 January 2026

20 November 2025 min Read

Few artists have reshaped our perspective on the world like Georgia O’Keeffe. Over the course of seven decades, she reinvented painting—magnifying a flower until it became a landscape and transforming a desert bone into a symbol of eternity. “To see takes time,” she once said, and her life was exactly that: a lifelong act of seeing. From her Midwestern roots to her luminous New Mexico vistas, O’Keeffe built a visual language that was radical yet intimate, personal yet universal. Let’s follow her journey across color, form, and the vast American landscape—meet Georgia O’Keeffe in 10 paintings.

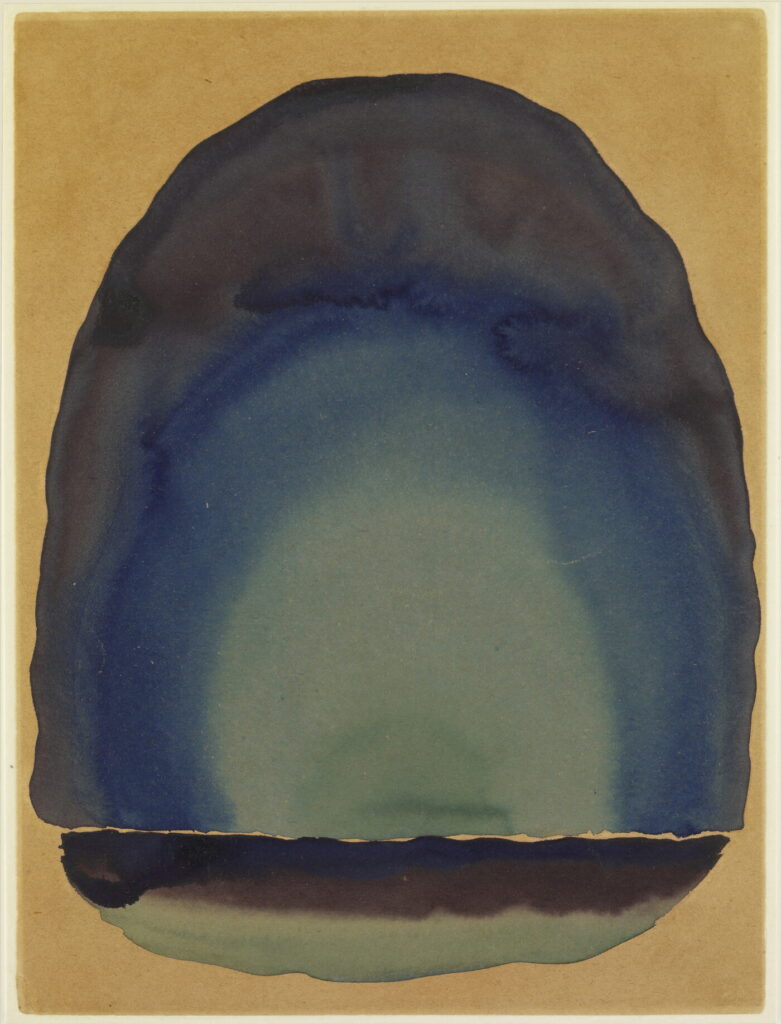

Georgia O’Keeffe, Light Coming on the Plains No. III, 1917, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Museum’s website.

Teaching art in Canyon, Texas, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) would rise before dawn to watch the light break over the empty horizon. Those quiet mornings inspired her watercolor series Light Coming on the Plains, where soft washes of color capture the moment night becomes day.

Here, she began to abandon realism and explore abstraction, guided by her mentor Arthur Wesley Dow, who taught that art should express emotion through harmony. It was the beginning of her lifelong pursuit of the vast and the essential.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue and Green Music, 1919–1921, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Museum’s website.

Back in New York, O’Keeffe lived amid the pulse of modernism, skyscrapers rising, jazz spilling from radios, and new ideas of abstraction everywhere. In Blue and Green Music, she translated musical rhythm into waves of color and form, visualizing sound as movement. The painting reflects both that intellectual excitement and O’Keeffe’s own independence; she was making her own kind of music.

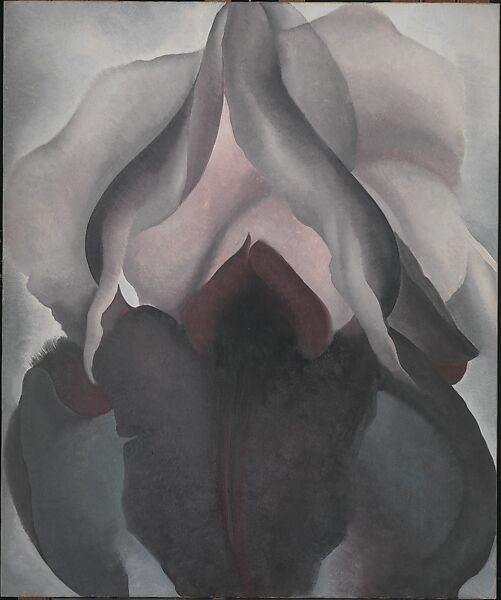

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Iris, 1926, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

When O’Keeffe painted Black Iris (formerly called Black Iris III), she zoomed in so close to the flower that it became almost abstract, a velvety landscape of folds and shadows. She wanted viewers to really see a flower, stripped of prettiness. “Nobody sees a flower really,” she said. Critics, however, projected Freudian interpretations, seeing sexuality in her work. O’Keeffe rejected that: “When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they’re really talking about their own affairs.” Instead, this iris represents her search for purity of form, and her refusal to let others define her art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Oriental Poppies, 1927, Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

In Oriental Poppies, two brilliant red flowers fill the entire canvas, dissolving their boundaries into pulsating fields of color. It’s a daring, sensual image that made O’Keeffe famous; a still life turned into a landscape of emotion.

She wanted to slow the viewer down, to make the ordinary extraordinary. As she said, “I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look.” Painted at the height of her New York success, this work captures her bold confidence and her power to turn something delicate into something monumental.

Georgia O’Keeffe, The Shelton with Sunspots, 1926, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Museum’s website.

From her apartment on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel, O’Keeffe painted the city as pure geometry. The Shelton with Sunspots reduces New York’s skyline to glowing forms, a cathedral of modern light.

She was fascinated by urban rhythm but also uneasy with it. These paintings mark her brief love affair with the city; beautiful, structured, and already fading into abstraction as her heart turned westward.

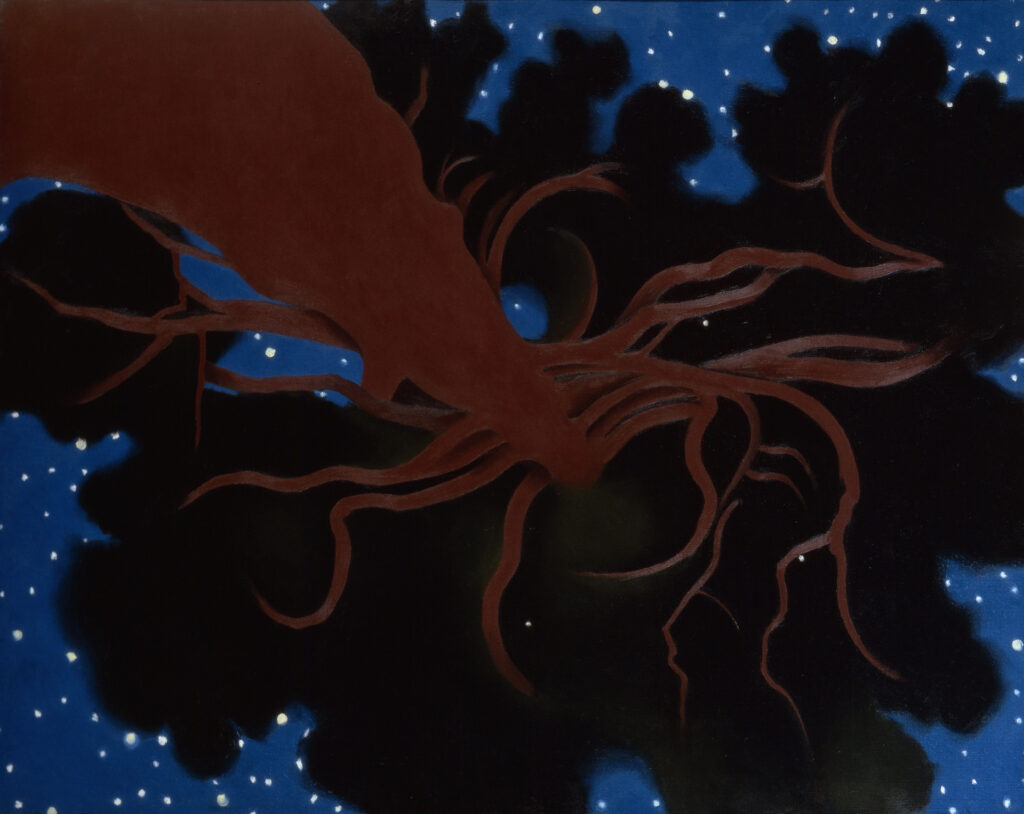

Georgia O’Keeffe, The Lawrence Tree, 1929, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

When O’Keeffe first visited New Mexico in 1929, she felt instantly at home. One night, lying on a bench beneath D.H. Lawrence’s beloved pine tree, she looked up through its branches and painted The Lawrence Tree.

The image seems to stretch toward infinity, the tree trunk growing downward, the stars above forming a canopy. This inversion of perspective mirrors her own creative shift: O’Keeffe had turned her gaze away from man-made towers toward the ancient sky. The Southwest would become her muse for life.

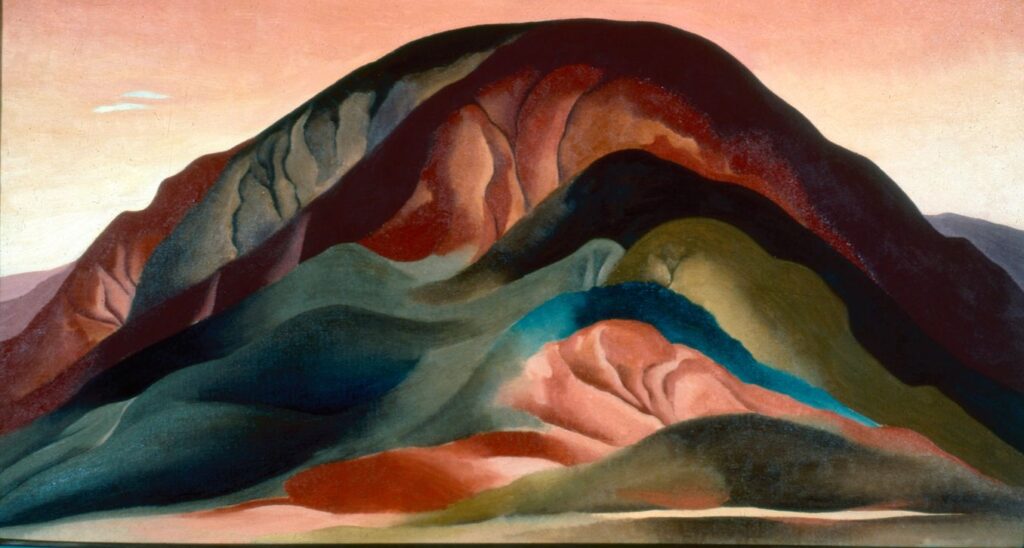

Georgia O’Keeffe, Rust Red Hills, 1930, Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso, IN, USA. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

In New Mexico, O’Keeffe painted the earth as if it were alive, sensuous, and sculptural. Rust Red Hills is stripped of all detail: just bands of red and ochre rolling beneath a pale sky. The land itself becomes a body, breathing and monumental.

These works signaled her rebirth as an artist. After years in New York, she found strength in the desert. “The color up there,” she wrote, “is different. The air is wonderful. I feel at home.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, 1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Obelisk Art History.

While Depression-era artists searched for “American” subjects, O’Keeffe found hers in the bleached bones of the desert. In Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, she floats a skull before bands of color, both flag and landscape, both death and endurance. To her, the bones were not macabre but full of life. “They pleased me. And I have enjoyed them very much in relation to the sky.” It’s a quietly patriotic image, a modernist’s version of the American spirit– resilient and stripped to its essence.

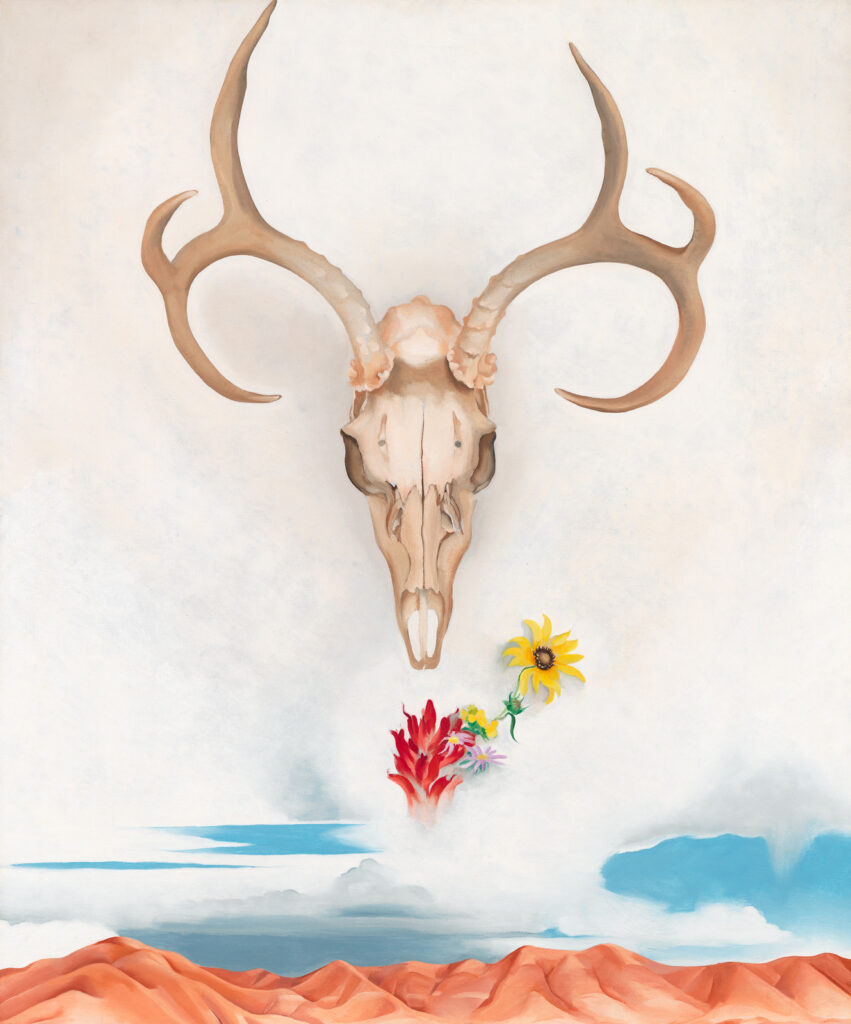

Georgia O’Keeffe, Summer Days, 1936, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

In Summer Days, Georgia O’Keeffe combines the precision of her earlier floral paintings with the vast stillness of the desert. A deer skull floats majestically against a backdrop of pale blue sky and distant red cliffs, surrounded by desert blooms that seem both fragile and eternal.

Painted after O’Keeffe had settled in New Mexico, this work distills her deep connection to the region’s landscape and symbolism. The skull, far from a memento mori, becomes a timeless emblem of nature’s resilience—a bridge between life and death, spirit and earth.

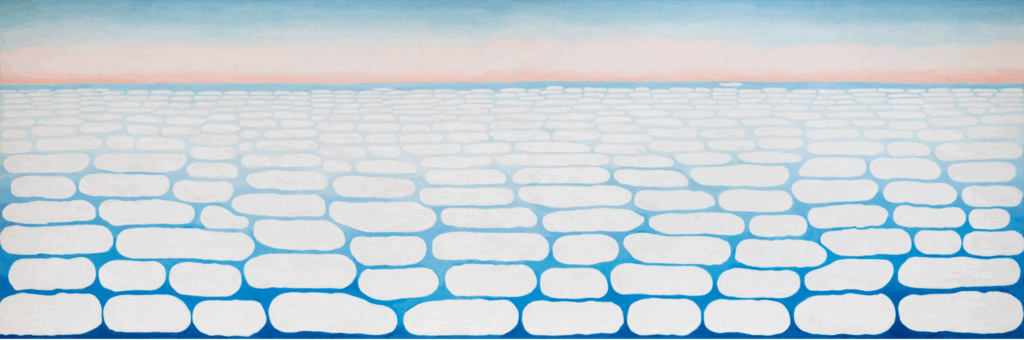

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sky Above Clouds IV, 1965, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Reddit.

In her late 70s, O’Keeffe would fly frequently, mesmerized by the view from above. Sky Above Clouds IV, over seven meters wide (almost 23 ft), captures a horizonless expanse of pink and white. It’s as if her beloved desert had risen into the heavens. Her eyesight was failing, but her ambition soared. “I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life,” she said, “and I’ve never let it keep me from a single thing that I wanted to do.” This monumental painting is her farewell to earth—and her ascension into pure space.

The artist’s work is a lifelong meditation on how to look and how to feel what we see. From the prairies of Texas to the skies of New Mexico, she transformed the familiar into the eternal. Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings invite us to slow down and really see, not just with the eyes, but with attention.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!