Halloween Monsters: What Our Fears Reveal About Society

Halloween monsters have long served as mirrors of human fear and imagination. From vampires and witches to zombies and digital phantoms, they reveal...

Errika Gerakiti 30 October 2025

Did you know that some of the most admired painters’ pigments in art history are also among the most toxic? The pursuit of beauty has sometimes come with consequences far more dangerous than we might imagine. Here are three of these remarkable colors and some stories behind their lethal charm.

Some art are made at the expense of the artist’s physical and mental well-being, and sometimes even their life. The well-known (and controversial) performances Rhythm 0 by Marina Abramović and Shoot by Chris Burden are perfect examples of how vulnerability and high stakes can become part of artistic practice. But art can also unsettle social norms with unexpected materials loaded with meaning and history. One only has to think of Piero Manzoni’s iconic Artist’s Shit or Self, the ongoing work, in which Marc Quinn uses his own blood to create sculptural self-portraits.

Francisco Goya, Self-Portrait, 1815, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Many painters have worked with pigments that—often without knowing it—were toxic and physically damaging. And in some cases, even more intriguingly, artists were fully aware of the danger yet continued to use these materials, as they were considered chromatically unique or luxurious. In fact, such stories have helped fuel the mythology surrounding certain artists, such as Goya or Caravaggio, who are believed to have suffered from saturnism after prolonged exposure to lead white.

Do you know any of these remarkable colors? Some may surprise you more than others, but their stories certainly won’t leave you indifferent. Here are some of the most toxic painters’ pigments in the history of art:

Scheele’s green pigment powder. Photograph by Hochschule Luzern D&K via Material Archiv.

Scheele’s Green, also known as “Paris Green”, is a bright green pigment created around 1775 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, using compounds of copper and arsenic (looking good, right?). Its invention absolutely revolutionized the world of color with its intensity and relative stability, but it also concealed an invisible danger: Its toxicity could cause serious illness and, in extreme cases, death!

Throughout the 19th century, this color was widely used in artistic and decorative painting, as well as in more everyday objects such as wallpapers, upholstery, textiles, fashionable garments, and even children’s toys.

1860s dress from the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada. Photograph by Suzanne McClean. University’s website.

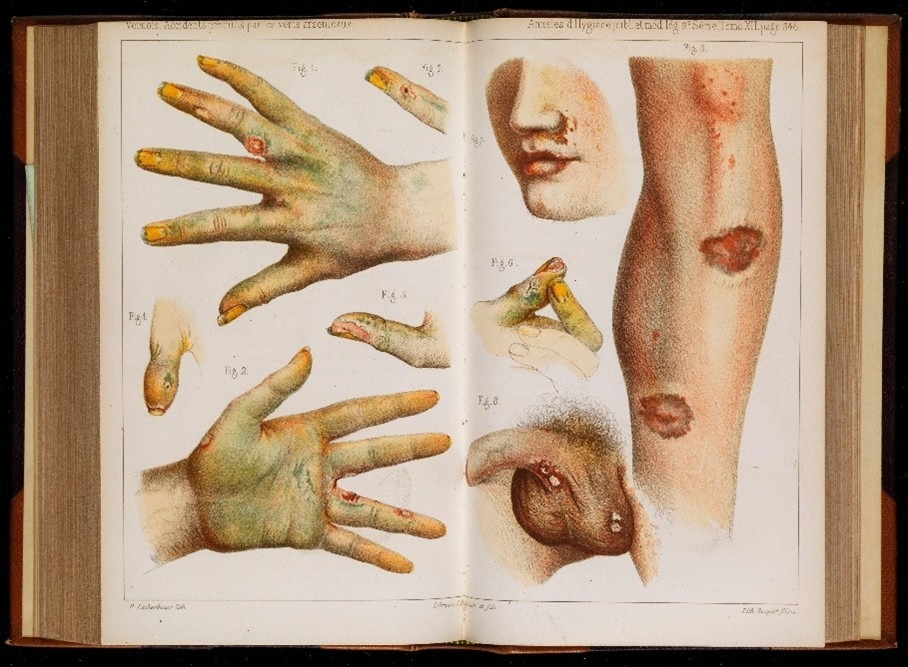

There is no need to insist on the fact that arsenic is a highly toxic element. In fact, in damp environments and in the presence of mold, arsenical pigments can release extremely poisonous vapors. Prolonged exposure could cause skin irritation, respiratory problems, vomiting, extreme weakness, and other symptoms of poisoning.

Given its common uses, it is easy to imagine who was most exposed: painters, decorators, textile workers, and individuals who regularly wore arsenic-dyed clothing, especially actresses and dancers.

By the mid-19th century, the risks of arsenic pigments became already widely recognized. The first medical warnings date from the 1830s–1840s, thanks to chemists such as Leopold Gmelin. And in 1861, the death of Matilda Scheurer, a young worker who made artificial flowers dyed with arsenical green, shocked the press and made the real danger of the pigment absolutely impossible to ignore. But these warnings did not have as much impact as we would imagine…

Illustration from a French medical journal in 1859 showing typical damage on hands when exposed arsenical dyes, 1859, Wellcome Collection, London, UK. The TMC Library.

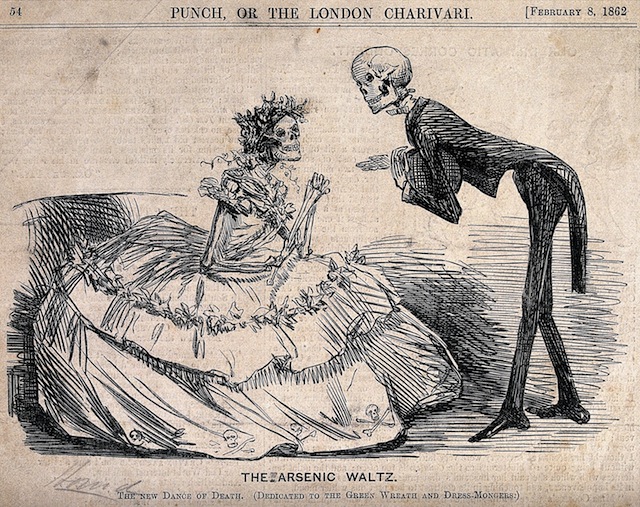

The pigment continued to be used because it was inexpensive, visually striking, and (of course) highly fashionable—three deadly incentives. It was in this climate that the Victorian satirical press began portraying women who wore dresses dyed with arsenical green as true “victims of fashion” in the literal sense. Caricatures in publications such as Punch depicted elegant women transformed into “walking poison,” highlighting the lethal nature of the pigment and showing just how far fashion could push the human body toward physical ruin.

The Arsenic Waltz, illustration from Punch, 1862, Wellcome Library, London, UK. Library’s website.

Known since antiquity, lead white was one of the most prized and important pigments of occidental painting for its luminosity and exceptional hiding power until the 19th century, when zinc white and titanium white became more prevalent. Used in painting, ceramics, and decorative objects, it also became the basis of a deadly aesthetic ideal when incorporated into cosmetics.

The Greeks and Romans produced it by exposing lead plates to acetic acid vapours and carbon dioxide, yielding a very fine white powder. During the Renaissance, it became the preferred white for oil painting, particularly for the initial layers (or underpainting) and flesh tones. Moreover, we can find it in some of the most popular pieces, such as Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl With a Pearl Earring, c. 1665, Mauritshuis, Hague, Netherlands. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Lead white was also used as a cosmetic. Popular makeup such as ceruse or Venetian ceruse was, in fact, a mixture of lead and vinegar. Its use is associated with prominent figures such as Elizabeth I of England, who is believed to have applied it to achieve a pale, uniform complexion. Although the dangers of lead were only vaguely recognized at the time, those who relied on these products often became victims of their own pursuit of beauty.

George Vertue, Procession Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, c. 1600. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Lead is a powerful neurotoxin. It can cause tremors, fatigue, memory loss, and kidney damage. It is known that painters and manufacturers inhaled or ingested particles during the preparation and application of the pigment. As mentioned earlier, artists such as Caravaggio and Goya have been the subject of medical studies suggesting possible cases of saturnism, although no diagnosis can be considered conclusive.

Industrially, lead white continued to be used on a massive scale until well into the second half of the 20th century, when it began to be progressively restricted in paints and domestic products. Even today, it appears in the restoration of historical artworks and in certain traditional artistic practices.

Lastly—though certainly not least in impact—we arrive at cinnabar, an intense red pigment used from the Neolithic period to the present day. It appears at sites such as Çatalhöyük (Turkey) and across Mesoamerican cultures, where it was applied to bodies, bones, and sarcophagi as a symbol of life and renewal. In ancient Rome, it was the quintessential imperial red.

From Late Antiquity onward, alchemists such as Zosimos of Panopolis and Jabir ibn Hayyan described methods for synthesizing vermilion, a purer and more brilliant artificial form of the pigment. In China, cinnabar was essential in the production of red lacquer and in the paste used for imperial seals, carrying strong ritual and alchemical connotations.

A collection of Chinese carved cinnabar and black lacquer vases, a plate, and a bowl with a floral design, 20th century. Coronari Auctions.

Although cinnabar (mercury sulfide, HgS) is less bioavailable than other forms of mercury and poses relatively limited danger in its stable, finished state, its extraction, grinding, and occasional contamination with other materials—such as red lead—have historically presented significant risks. The danger was already recognised in ancient Rome. Pliny the Elder describes rudimentary masks worn by workers to prevent them from inhaling the dust.

A well-known modern example was reported in The New Yorker in 1986. A conservator identified under the pseudonym “Laura McBride” fell ill while working at home on a funerary textile from the Chancay period (1000–1500 CE). She developed fatigue, dizziness, and muscle pain, and medical tests revealed anaemia with basophilic stippling, a classic sign of lead poisoning. Further analysis showed that the pigment she believed to be pure cinnabar was, in fact, contaminated with red lead. Handling and preparing this mixture had caused her symptoms—a reminder that even ancient pigments can pose serious risks when used today.

Wall painting from Room H of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, Italy, ca. 50–40 B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

At The Met, we also find the Damascus Room (1707), a reconstruction of Syrian winter reception chamber (qa’a) typical of the late Ottoman period in Damascus, Syria. The room is decorated using the ajami technique, which combines gesso reliefs, metal leaf, enamels, and pigments such as cinnabar red. It stands as an extraordinary example of Ottoman luxury and of the longevity and danger of these materials.

The Damascus Room, 1119 AH/1707 CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

To understand the most catastrophic consequences of using this material, we turn to the large prehistoric site of Valencina de la Concepción (c. 2900–2650 BCE) in southern Iberia. Here, researchers have documented intensive use of cinnabar in funerary and ritual contexts. Human remains mostly associated with high-status women show extraordinarily elevated levels of mercury in their bones, in some cases hundreds of times higher than what is considered normal in modern populations.

The pigment was likely inhaled or ingested during ritual or technical activities involving its handling. This chronic exposure may have caused tremors, memory loss, fatigue, or kidney damage. The application of cinnabar to bodies and objects underscores its symbolic and aesthetic value, despite the lethal risks it carried.

The story of toxic painters’ pigments reveals a striking paradox: the pursuit of beauty often came at the cost of the artist’s health and safety.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!