10 Autumn Activities Inspired by Impressionist Paintings

Autumn is such a colorful season! Here are 10 activities inspired by Impressionist autumn paintings to enjoy during this time of year.

Andra Patricia Ritisan 22 September 2025

In the final years of the 19th century, the art scene in Zagreb, Croatia, was pretty vibrant. The various ideas that circulated among artists occasionally resulted in conflicts between the old and the new. A young and shy Slava Raškaj, living in permanent silence, was a girl who wanted to create watercolor paintings. Not only did she achieve mastery in the technique, but she also mirrored the finest Impressionist aesthetics.

Slava Raškaj was born into an upper-class family in the rural area of Ozalj, in the then-Austro-Hungarian Empire. Deaf since birth, she felt excluded from the world in which spoken words have too big an importance in communication. She first saw her mother and older sister drawing and painting, and soon it would become her way of expressing herself and overcoming loneliness.

Thanks to her fairly privileged background, she went to a specialized school for deaf children in Vienna, where she also got the opportunity to learn and practice drawing. After coming back to her hometown, a local teacher spotted her talent. Soon after, she would go to Zagreb for further education.

Slava Raškaj, Self Portrait, 1898, Moderna Galerija, Zagreb, Croatia.

At the time when Slava Raškaj grew up, deafness was considered a mental disability or sometimes referred to as “mental retardation”, a term that was widely in use back then. By these standards, she was unlikely to marry and even less likely to work productively. Unfortunately, the concepts of inclusion and accessibility didn’t exist at that time.

Furthermore, women’s art didn’t have much prestige, as it was mainly seen as a side hobby, complementing woman’s “principal roles” in society. Most importantly, Raškaj found her own style in watercolor, a method which at the time and in the place she lived, was not considered particularly “important”.

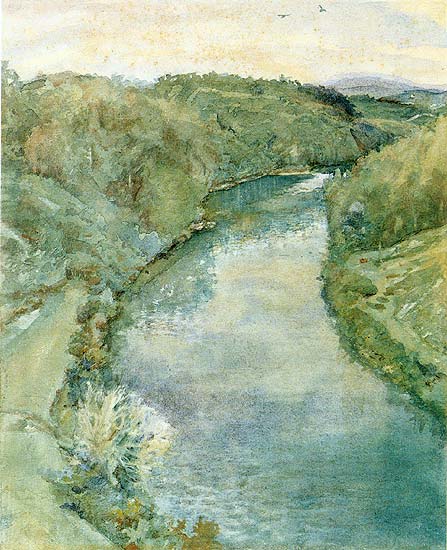

Slava Raškaj, The Kupa River near Ozalj, ca 1890. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The Kupa River near Ozalj is one of Raškaj’s earliest preserved works and she made it when she was around 13 years of age. The colors and style already show her strong affiliation with the principles of Impressionism. Aside from going to Vienna for primary education, Raškaj traveled to Venice and Paris.

The lack of support and opportunities for her to overcome negative thoughts and isolation in silence is considered one of the factors of her mental illness – depression. In 1900, at the age of 23, she started showing symptoms of clinical depression. Soon after, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital where she spent the last years of her life. She was rarely able to paint and never able to finish any work during these times. Slava Raškaj died of tuberculosis in 1906, aged only 29.

One can easily conclude that the story of Slava Raškaj’s artistic career is a big what-if that intrigues all art historians who come across her work.

Raškaj grew up surrounded by nature. It isn’t surprising that landscapes became some of her first sources of inspiration. The deep views through the forests and rivers of her region served as a great motif for watercolors and for what Impressionists are known for – painting outside, en plein air. Impressionists broke the Academic norm of painting inside the atelier; they were not the first artists to practice outdoor painting, but they definitely made it a more common choice among future artists. Meanwhile, their works were often frowned upon by critics as “unfinished.”

Claude Monet’s piece Impression, Sunrise was completed in 1872, about 25 years before Slava Raškaj started studying painting in Zagreb. In the meantime, the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements had found their grounds all over Europe, and in Zagreb, there were numerous artists who formed the well-known Zagreb Colorful School, heavily based on the legacy of Impressionists.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France.

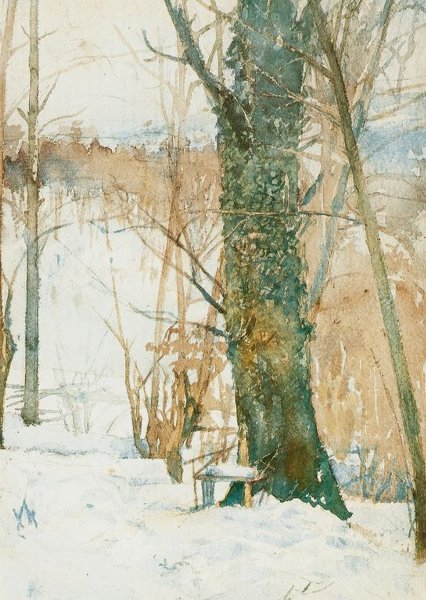

Slava Raškaj, A Tree in the Snowy Landscape, 1900, Moderna Galerija, Zagreb, Croatia, source: Hrvatska enciklopedija.

The depiction of nature in winter in A Tree in the Snowy Landscape is a fine example of Raškaj’s mature works. The Impressionist manner of atmospheric perspective gives a subtle but certain depth to the composition. Light purple tones give structure to the snowy surface, while the background trees lose clarity.

The most famous representative of Zagreb Colorful School was Vlaho Bukovac, a painter who found the perfect balance in creating for a conservative public but at the same time bring up an incredible amount of innovation. While choosing academically acceptable topics and compositions, he gave his painting the vibrant lighting techniques of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements.

In fact, Slava Raškaj was first promised to be accompanied by Bukovac in her development as an artist. However, he refused with the explanation that he was too busy to teach, so Raškaj got eventually attended by another well-known painter from Zagreb, Bela Čikoš Sesija.

Bela Čikoš Sesija had a different approach to painting than Vlaho Bukovac. In short, the two artists were different in some fundamental views on modernity. While Bukovac was able to innovate and attract positive feedback at the same time, Čikoš Sesija was mostly following traditional academic patterns, although his artistic style is also associated with Symbolism, and while the Colorful trend was at its peak, he was a slight outsider. He often applied darker values while applying the golden-tone lighting only to showcase the motifs under the spotlight.

Bela Čikoš Sesija, Homer teaches Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe to sing, 1909, Institute for Croatian History, Zagreb, Croatia.

In any case, Slava Raškaj developed a strong personal style regardless of her teacher’s affiliation. In spite of Čikoš Sesija’s preference for oil painting, she remained faithful to watercolor as her preferred painting method. Although Čikoš Sesija instructed her to draw the human body and anatomy, she never found herself in these motifs. Nevertheless, the teacher was deeply impressed with Raškaj’s artistic development, especially in her color choices.

Raškaj’s favorite place to paint in Zagreb was the Botanical Garden, while rural areas remained her main focus of interest. There is no documented work of Slava’s depicting an urban scene in Zagreb, but her way of seeing urban beauty is through the water lilies she observed at the Botanical Garden.

Slava Raškaj, Water Lilies, 1898, Moderna Galerija, Zagreb, Croatia.

The depiction of Water Lilies is another example in which art historians draw comparisons to Claude Monet. Curiously, the French master of Impressionism painted water lilies in his last years, when he was well into his 80s. It was one of his last sources of inspiration, an idea that came after decades of experience.

Slava Raškaj didn’t enjoy the luck to reach nearly as advanced age. However, she painted several compositions with water lilies and thus announced a shift in style and direction she could have followed had she lived. This work brings her closer to Symbolism from her teacher and even to flowery forms of Art Nouveau – the Secession.

In the Croatian context, very few artists have that level of control over the watercolor technique Slava Raškaj had. Watercolor is, in reality, quite hard to master. The artist needs to find the perfect balance between the quantity of water and the amount of pigment to put on the paper, and the margin of error is very narrow. It is an ancient technique, popular among the masters of illustrated manuscripts as the oldest examples date back to Ancient Egypt. In most parts of the world, it has been a prestigious form of painting for centuries, but the Impressionist painters did not use it a lot. Croatian painters of Raškaj’s lifetime even less.

In conclusion, Slava Raškaj achieved an incredible feat. In a time when the world was less connected and the availability of learning materials much more scarce, she mastered a technique rarely used by her contemporaries and compatriots. Additionally, she even transferred some of the main aesthetics of Impressionism from the common oil painting to her watercolors.

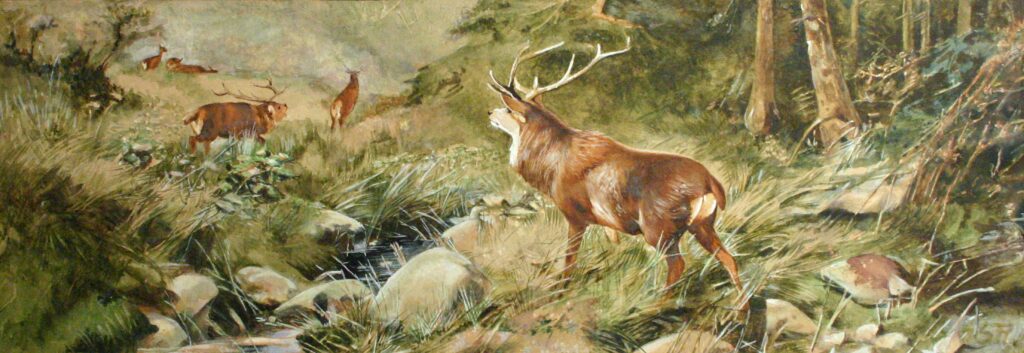

Slava Raškaj, Deer in the Battle, 1897, Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

She still remains a slightly mysterious artist, even in the context of Croatian and Balkan art. Very few of her works are on display for the public to see. There are many counterfeits of her works, whose authors had some awkward ideas of changing the narratives about her. Many of her works got lost and destroyed. Ahead of the last big retrospective exhibition about her in 2008, the curators had to do extensive work to display Raškaj’s paintings from private collections.

This is a story about women in art history, disabilities, and mental health. All these “stories” influenced the reality of Slava Raškaj’s work and life.

“Sjaj genijalne slikarice” Nacional Magazine. 26 May 2008. Accessed 1 Dec 2021.

Sebastijan Ribaric, “Slava Raškaj – između simbolizma i secesije,” Undergraduate thesis at the University of Rijeka, 2020. Accessed 1 Dec 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!