Fanny Eaton—Pre-Raphaelite Muse from Jamaica

Fanny Eaton was a regular model for the Pre-Raphaelites during the 1860s and features in a number of famous works. Yet for most of the last century,...

Catriona Miller 19 February 2026

René Magritte (1898–1965) stood at the heart of Surrealism, yet his art leaned toward a more figurative vision. He transformed ordinary objects into puzzles that questioned how we see and interpret reality. Through his paintings, Magritte invited viewers to rethink language, perception, and the fragile link between words and things. Let’s explore 10 René Magritte paintings that capture the artist’s essence and his enduring fascination with mystery.

René Magritte faced a deep tragedy as a young boy. In 1912, his mother died of suicide, drowning herself in the Sambre river at Châtelet, where the family lived. Her body was discovered 16 days later, her dress covering her face—a haunting image that inspired several of artist’s works in 1927 and 1928.

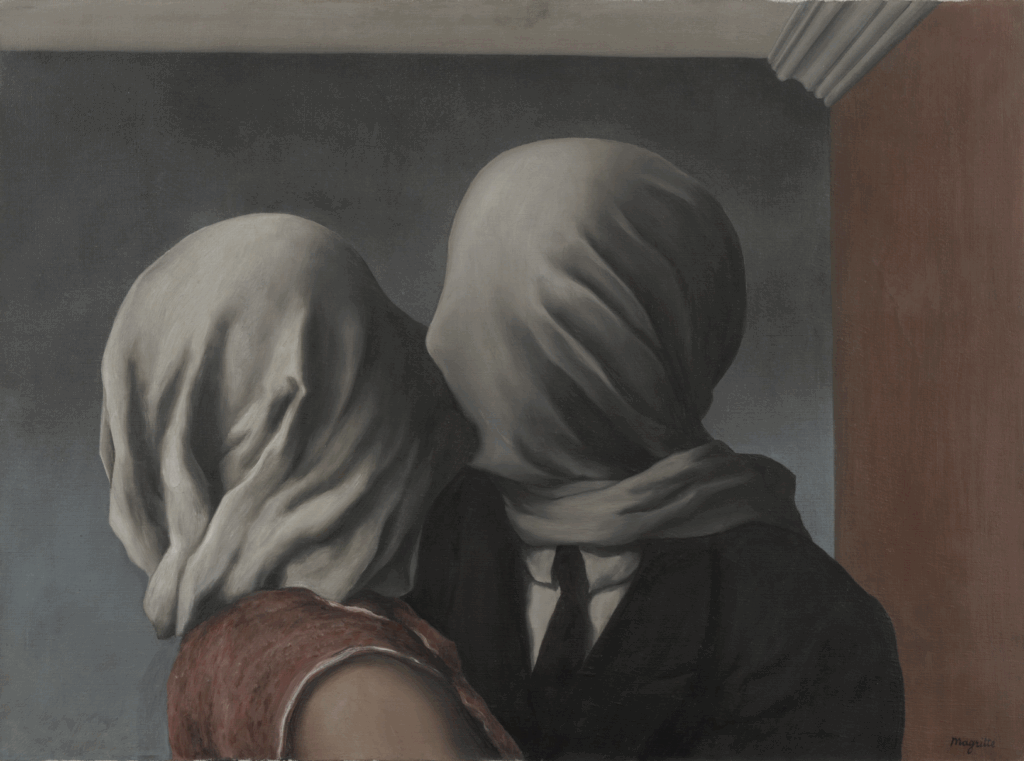

In paintings like The Lovers, a fabric barrier turns an intimate kiss into isolation and frustration, highlighting tension rather than passion. Magritte rejected psychoanalysis and opposed the idea that art expressed personal inner worlds. He insisted that his work commented on reality itself, not on private trauma. Art critics later suggested connections to his mother’s death, but Magritte never confirmed this interpretation.

René Magritte, The Lovers, 1928, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA. © 2025 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1927, René Magritte moved from Brussels to Paris, where he joined the Surrealist circle. He became friends with André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, and quickly engaged with the group’s ideas. Magritte developed a distinctive style, blending illusionistic, dream-like qualities with ordinary objects placed in unexpected contexts. He stayed in Paris for three years and emerged as a leading figure in the movement.

On December 15, 1929, he contributed to the final issue of La Révolution surréaliste (no. 12) with his essay Les mots et les images, exploring how words and images interact. Many René Magritte paintings reflect this playful tension, giving new meaning to familiar things. In The Treachery of Images, for example, a pipe appears, yet it is only an image, not an actual pipe. Magritte humorously remarked that if it were real, one would need to fill it with tobacco.

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe), 1929, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA. © C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

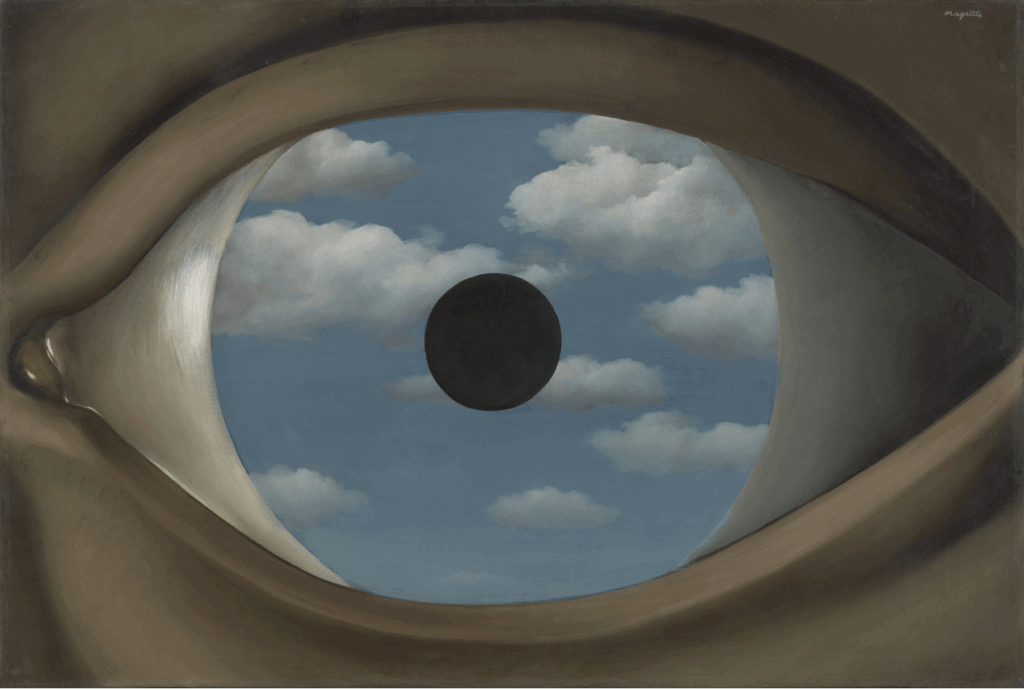

The human eye fascinated many Surrealists, as they saw it as a bridge between the self and the external world. In The False Mirror, a single eye dominates the canvas, staring at the viewer with striking realism and texture. Man Ray, who owned the painting from 1933 to 1936, observed that the work reflects a duality, showing how the eye both perceives and is perceived.

René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1929, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA. © 2025 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Early in his career, René Magritte stayed rent-free in London at the home of British Surrealist patron Edward James, where he studied architecture and painted. James appears in two 1937 René Magritte paintings: The Pleasure Principle and Not to Be Reproduced.

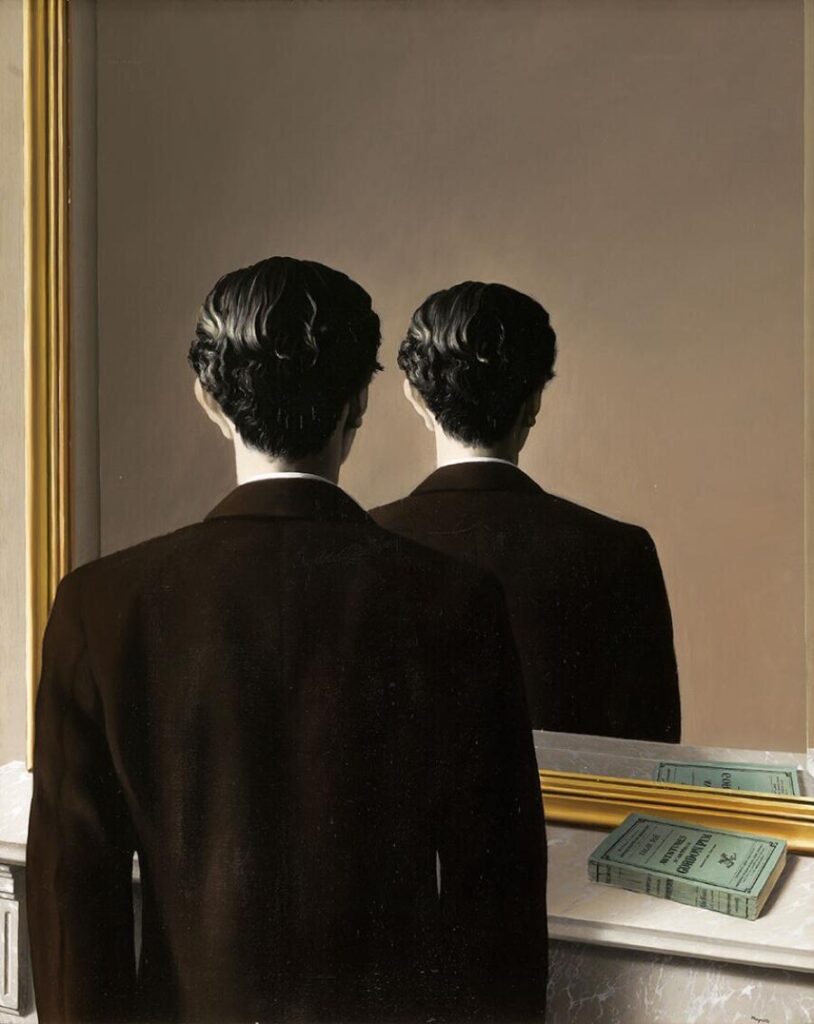

In Not to Be Reproduced, a man stands before a mirror, yet the reflection shows the back of his head instead of his face, creating a disorienting and unsettling effect. This visual contradiction challenges our expectations of mirrors, which normally reflect an accurate image, and raises questions about identity and the relationship between inner self and external reality. Additional details enhance the scene: a book by Edgar Allan Poe rests on the mantel and appears reflected correctly, its title perfectly visible.

René Magritte, Not to Be Reproduced, 1937, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Time Transfixed was another René Magritte painting created for Edward James. Its original title literally translates to “Ongoing Time Stabbed by a Dagger,” which Magritte preferred, as it reflected his playful intent. He hoped James would hang the painting at the base of his staircase, so the train would seem to “stab” guests on their way up, but James placed it above the fireplace instead.

Magritte combined philosophy and psychology to challenge perception, juxtaposing two unrelated objects to suggest a third, unseen element. In this case, a train and a fireplace occupy the same composition. Though the fireplace is domestic and the train industrial, they are linked through smoke. Viewers naturally connect the locomotive’s exhaust with the chimney plumes, revealing the painting’s subtle poetic effect.

René Magritte, Time Transfixed, 1938, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Perspective II, Manet’s Balcony is one of René Magritte’s paintings that reimagines famous works through a surreal lens. It pairs with Perspective I, David’s Portrait of Madame Récamier, creating a striking dialogue between the two compositions. In Manet’s Balcony, human figures are replaced by coffins, introducing an unsettling and mysterious atmosphere. Magritte explained that his paintings reveal nothing but evoke mystery; when viewers asked what they mean, he insisted the question itself is misleading, as mystery is inherently unknowable.

René Magritte, Perspective II, Manet’s Balcony, c. 1950, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, Gent, Belgium.

René Magritte described his approach as portraying objects and their relationships in a way that no habitual concepts or feelings are necessarily associated with them. This philosophy shines clearly in Personal Values, a painting set in a seemingly ordinary bedroom filled with oversized, human-sized objects. A comb, a wine glass, and a shaving brush occupy the space, each rendered with realistic detail. By presenting familiar items in an unexpected and unsettling way, Magritte challenges common sense and invites viewers to reconsider their assumptions about reality.

René Magritte, Personal Values, 1952, San Francisco of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA, USA. © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

René Magritte transformed ordinary objects in unusual settings to create strikingly poetic imagery. He described painting as placing colors so that familiar items merge into a single, disciplined poetic vision, free of symbolic meaning. Although he lived a quiet, middle-class life in Brussels, Magritte made the everyday extraordinary.

In Golconda, countless men in dark overcoats and bowler hats hover above a suburban landscape, creating a surreal, dreamlike spectacle. The artist’s environment and attire mirrored the floating figures, hinting at a subtle self-portrait, while the title came from his poet friend Louis Scutenaire, who also appears in the scene as the large man by the chimney.

René Magritte, Golconda, 1953, Menil Collection, Houston, TX, USA. © C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Hegel’s Holiday is a painting that pairs two objects with opposite functions—repelling and containing water. Magritte preferred this title over The Philosopher’s Holiday, writing that it reflects a higher conception of life rather than distorted or cruel interpretations. He rejected views that associated Hegel with violence or prejudice, insisting art should celebrate what is beautiful and good. This enigmatic work, as many of his paintings, features symbols that only he fully understood, creating a dreamlike tension between reality and imagination.

René Magritte, Hegel’s Holiday, 1958, private collection. Christie’s.

Surrealism aimed to free the mind by subverting rational thought and giving the unconscious full expression. Until the late 1920s, Surrealist painting favored biomorphic abstraction, often created through automatic techniques beyond the artist’s conscious control. René Magritte, however, adopted a figurative approach, using naturalistic, highly detailed depictions of ordinary objects to challenge the real world.

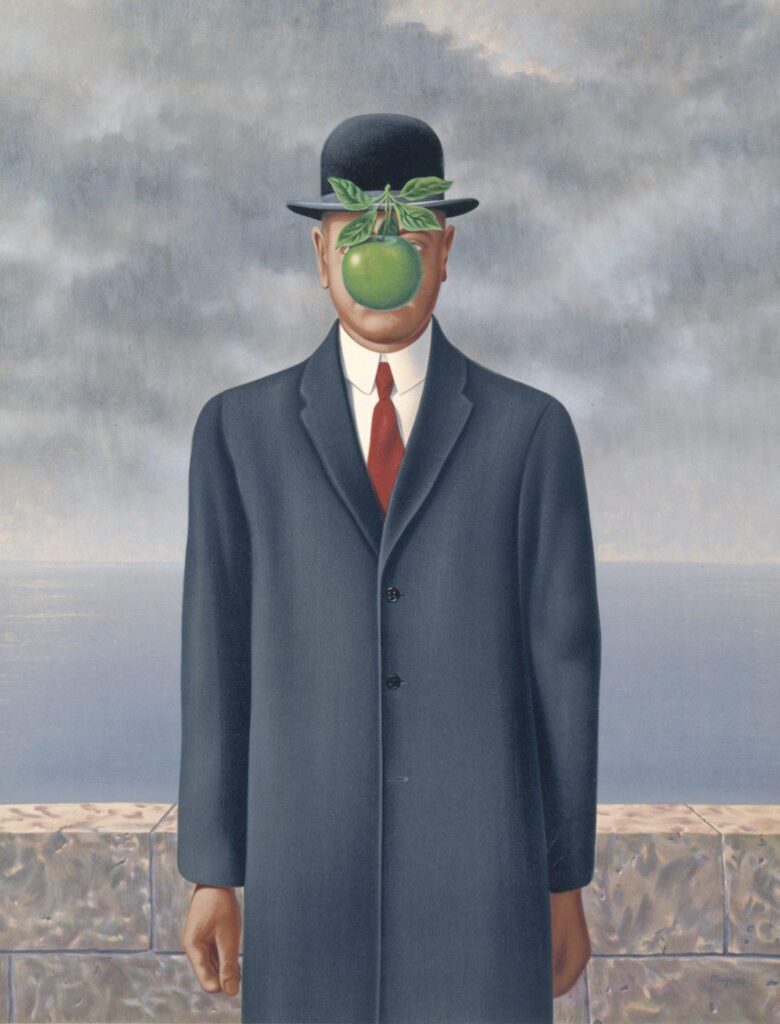

In The Son of Man, symbolism abounds: the apple references the Garden of Eden, embodying sin, temptation, and human mortality. The recurring figure of a man in a black suit, red tie, and bowler hat may reflect Magritte himself, who dressed in the same manner, though he mocked such interpretations as narcissistic.

René Magritte, The Son of Man, 1964, private collection. Forbes. © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!