Pauline Boty: The Untold Story of a Pop Art Pioneer

Pauline Boty was one of the pioneers of the 1960s’ Pop Art movement in Britain, of which she was the only acknowledged female member. Her...

Nikolina Konjevod 4 April 2024

Would it surprise you to learn that pop art aesthetics became popular in socialist Cuba at the very same time it was gaining fame across the USA and Europe? How is it possible that pop art, a style so deeply rooted in Western pop culture and capitalism, influenced communist propaganda? An iconic image of a famous political leader played an important part in this story.

Raúl Martínez was born in the central Cuban city of Ciego de Ávila in 1927. Before the Revolution, he had the opportunity to work and exhibit his early paintings in Europe and the United States, the latter of which would leave a lasting impact on his stylistic development as an artist. Nonetheless, any American influences Martínez might have incorporated into his work were soon to assume a distinctly Cuban flavor. On New Year’s Day of 1959, the rebel forces of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos marched victoriously into Havana, ending the five-year Cuban Revolution and beginning a radical period of political, economic, and social reforms that would reshape the entire country.

Though the personal liberties of citizens and freedom of the press were strictly limited by the new regime, government repression never reached the levels of severity that were experienced in the Soviet Union and many other communist states. Whereas socialist realism was imposed as the official style of Soviet art in the 1930s under Stalin and would remain so until the passing of Gorbachev’s “glasnost and perestroika” reforms in the 1980s, Cuban artists under Castro’s rule enjoyed a greater degree of expression than did their comrades overseas. For this reason, although Havana and New York City in the 1960s and 1970s may have seemed like two different worlds in most regards, an unlikely cultural exchange was taking place.

By adding elements of muralism and socialist realism to his works, Martínez managed to create a distinctly Cuban style of pop art. This style is well exemplified by his painting Roses and Stars, which depicts the poet José Martí surrounded by an iconic group of national heroes. From left to right, the back row is comprised of Simón Bolívar, Camilo Cienfuegos, Máximo Gómez, and Antonio Maceo. Directly to Martí’s right stands Fidel Castro and to his left stands Che Guevara.

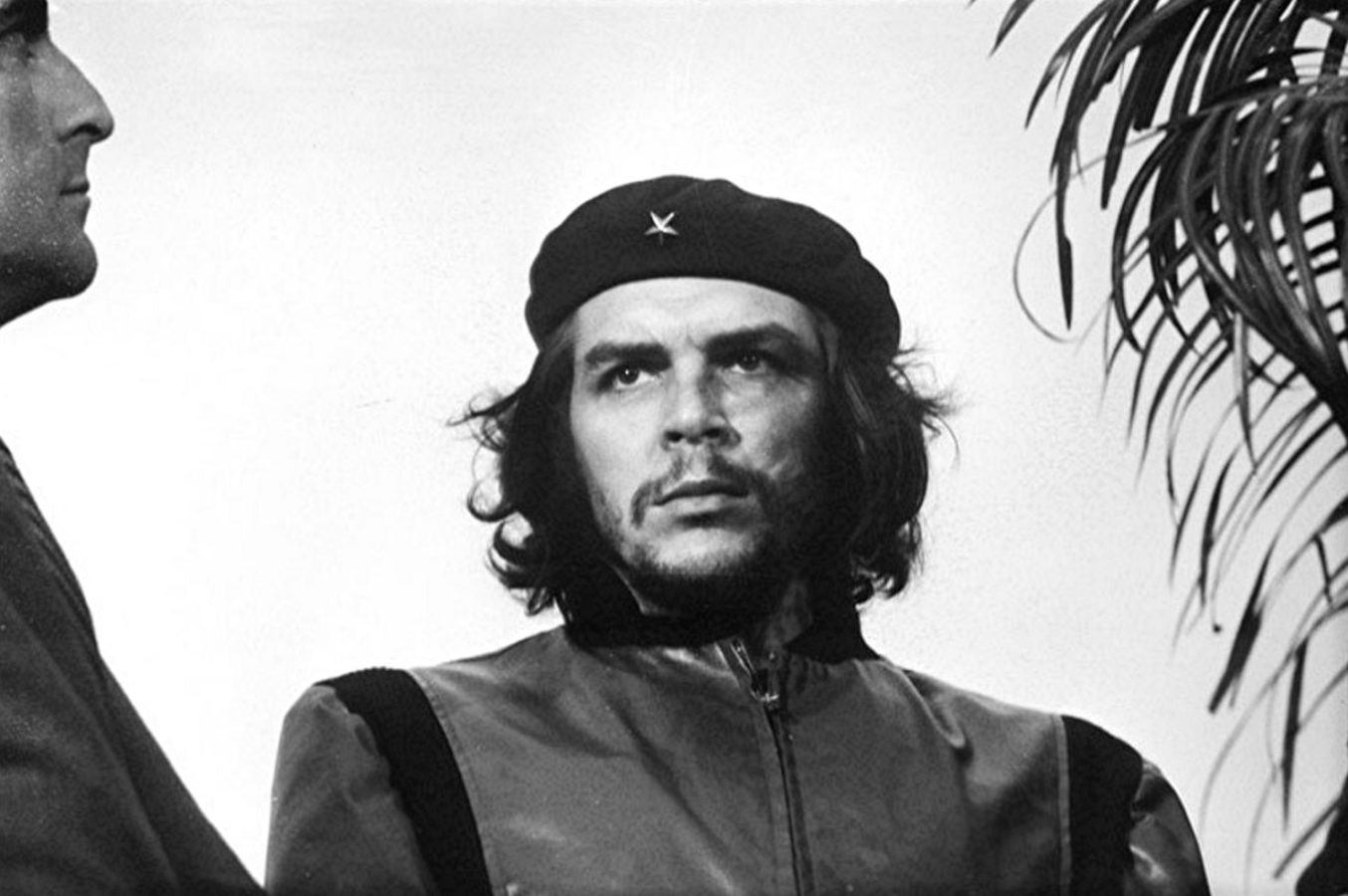

While vintage American cars and pop art were trending in Cuba, the island had an export that captured the hearts and minds of many youths in both Europe and the United States. The utopian idealism associated with the Cuban Revolution had a mass appeal in the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, an appeal which only grew stronger through the iconic figure of Che Guevara. The iconography of the revolutionary leader began with an image captured in 1960 by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda, which he would later title Guerrillero Heroico.

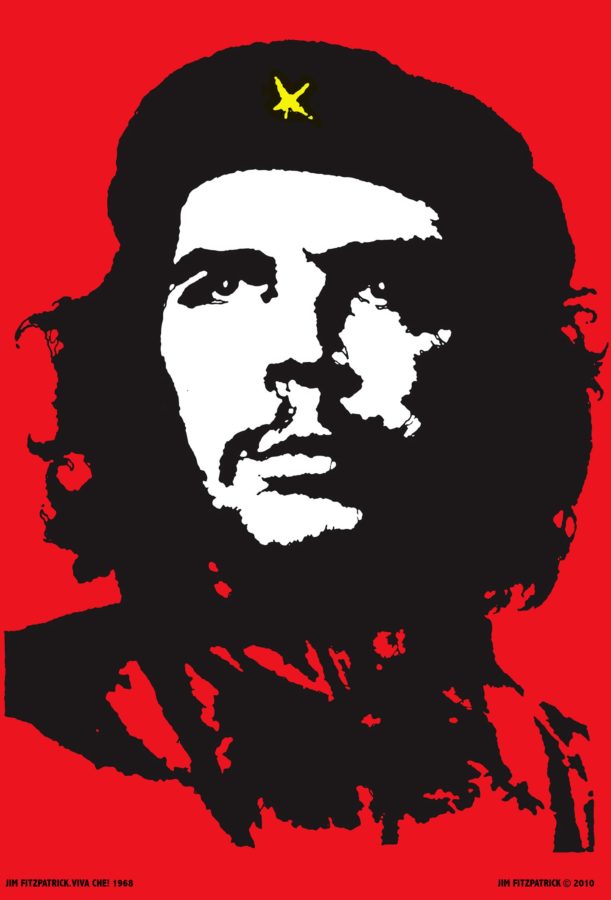

In 1968, one year after Che Guevara’s death fighting in a failed insurgency in Bolivia, Korda’s photograph was discovered in Europe by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick. As he found the image with the palm tree and the profile of the other man already cropped out, all that remained for Fitzpatrick to do was apply the red and black tones which would turn Che into a cultural icon.

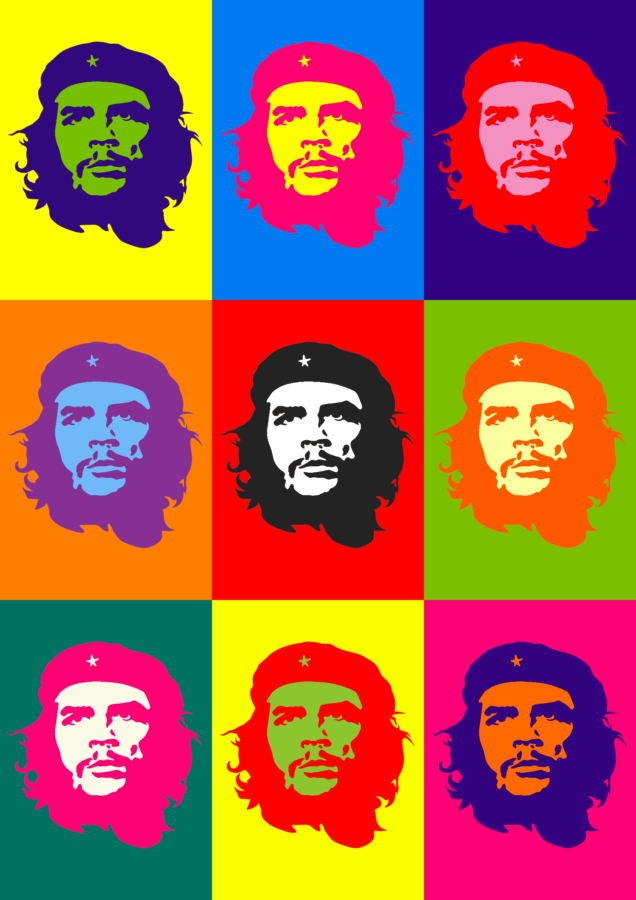

At the same time in New York City, Andy Warhol was enjoying the success brought to him by depicting American popular culture in a variety of innovative ways. By this time, one of his most iconic works was the silkscreen painting Marilyn Diptych, which featured a famous photograph of actress Marilyn Monroe represented fifty times on two opposing panels, the colors altering slightly from one image to the next.

This technique was reproduced by Gerard Malanga, a close associate of Warhol’s at the time, to create an untitled representation of Che Guevara in the same style, falsely attributing the work to Andy Warhol as he was in desperate need of money. Fitzpatrick’s version of Guerrillero Heroico, produced earlier that same year, can be seen in the center. Nonetheless, when the work was revealed to be a forgery, Warhol “authenticated” the painting in exchange for all the money Malanga had made from its sales. This marked Warhol’s first association with a communist-themed work, as he would go on to paint controversial portraits of Mao Zedong and Vladimir Lenin, as well as symbolic objects such as the hammer and sickle in the 1970s and 1980s.

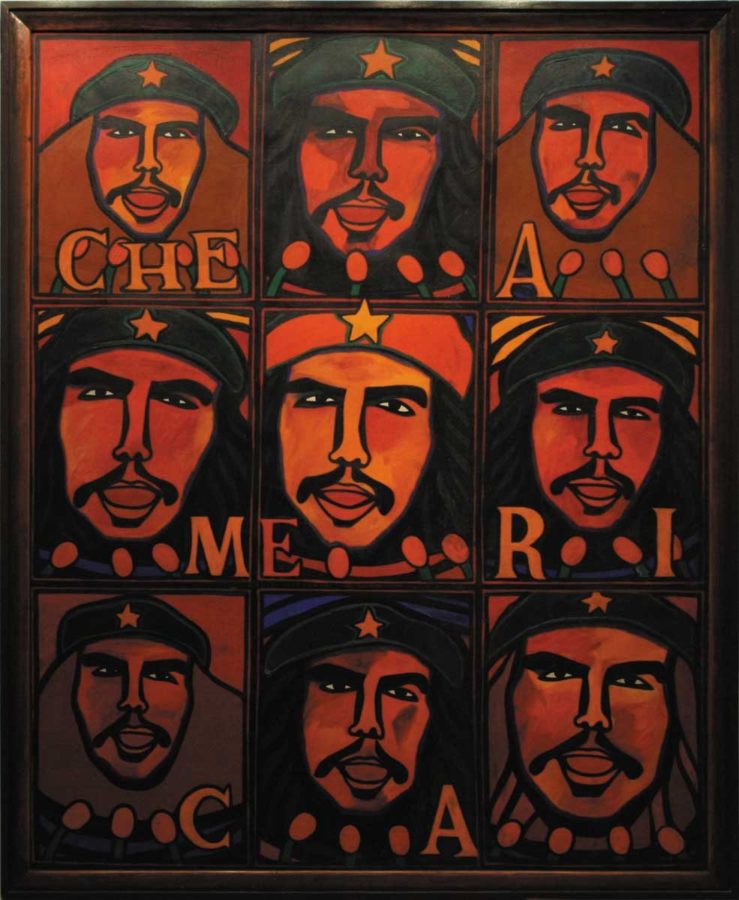

The year 1968 proved to be quite a posthumous journey for the fallen revolutionary. After Korda’s original photograph of Guevara was first altered in Ireland by Fitzpatrick and later in the United States by Malanga, it was time for the image to come full circle and return to Cuba. Thus, that same year, in a style clearly inspired by Warhol but at the same time very much his own, Raúl Martínez made his contribution to the legacy of the now-iconic guerrilla fighter in a work he appropriately titled Fénix.

Although the evolution of Alberto Korda’s photograph has indeed given Che Guevara the longevity of a phoenix, it is doubtful that the revolutionary would approve of the commercialism that his image has ironically come to be associated with. Today, much like Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, endless alterations of Guerrillero Heroico can be seen on clothing items, posters, and almost any other kind of popular, mass-produced merchandise one can imagine.

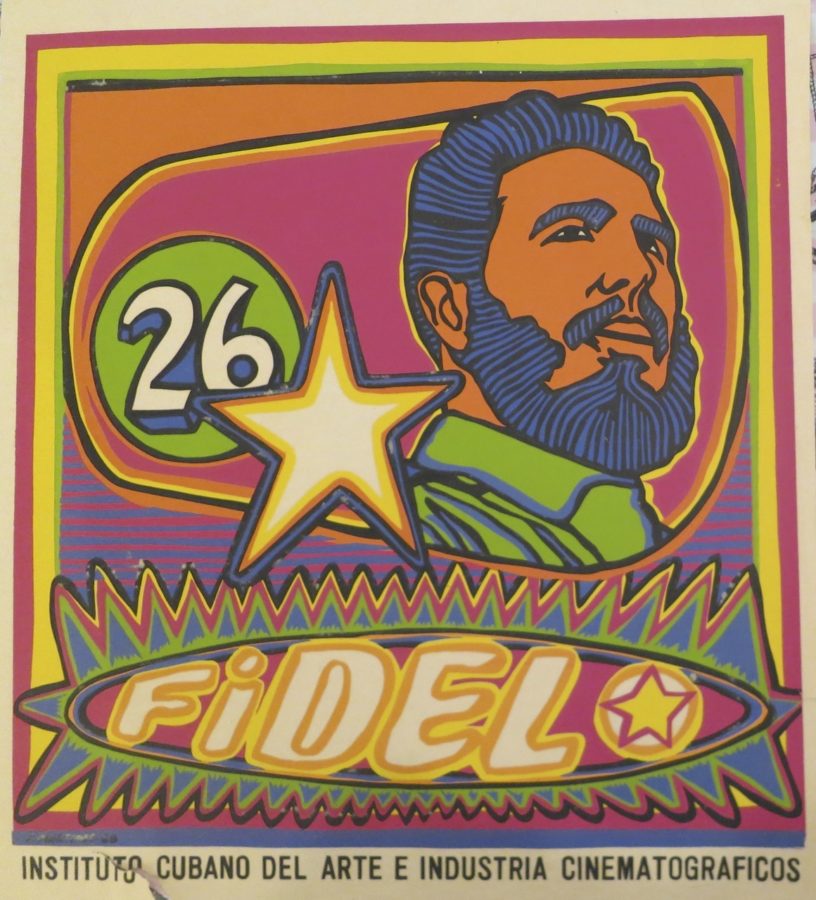

As was the case in other communist countries, politics is culture and culture is politics in Cuba. This reality is reflected in the work that Martínez completed when he worked for the Cuban Film Institute (ICAIC). Despite the constraints of tight government censorship and the isolation of the United States embargo, the artist still managed to introduce very innovative and modernist elements to his country’s art scene. One example is his silkscreen painting Fidel, which depicts the president in a style that is reminiscent of the comic book-like images frequently associated with Roy Lichtenstein, another New York City pop artist.

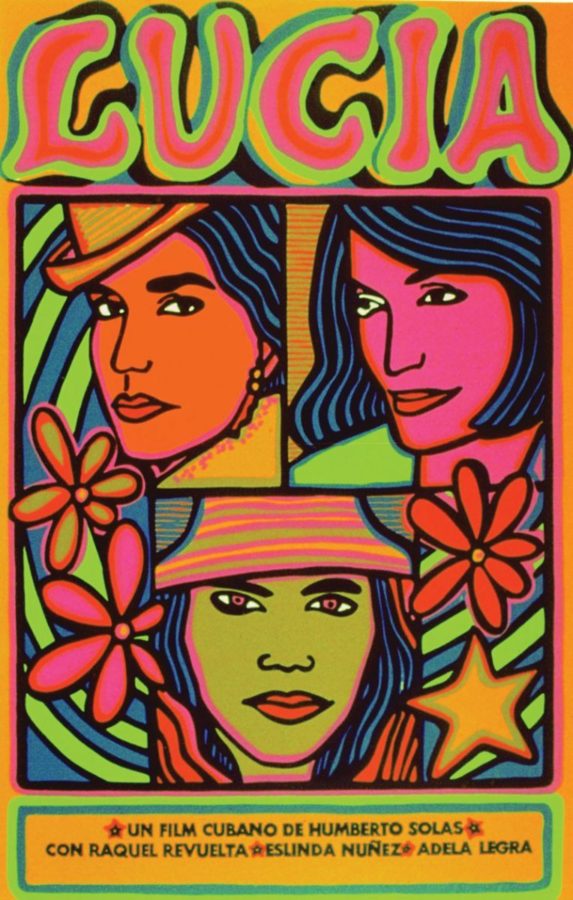

Apart from his explicit contributions to state propaganda in the form of painting portraits of revolutionary heroes, Martínez’s work at the Cuban Film Institute also dealt with the cultural sphere. The classic Cuban film Lucía, which won the Golden Prize at the 6th Moscow International Film Festival in 1969, tells the history of Cuba through the eyes of three different women, each with the same name. The first fights in the Cuban War of Independence from Spain, the second struggles against the regime of Gerardo Machado in the 1920s, and the third (naturally) participates in the Cuban Revolution that ultimately brought Fidel Castro to power. Raúl Martínez was commissioned to create the official poster for the film, which depicts all three Lucías in his recognizable style.

Martínez continued to be an innovating force in Cuban art and culture until his death in 1995. Many of his works can still be found today on the covers of film cases, magazines, posters, and other forms of printed media in Cuba. Moreover, his paintings continue to be exhibited internationally on loan from the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!