Joséphine de Beauharnais: Patron of the Arts

Joséphine de Beauharnais was born in Martinique as Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. She evolved into the sophisticated and cultured...

Maya M. Tola 20 May 2024

At the suggestion of his mother, Nelson Rockefeller commissioned Diego Rivera, a passionate Mexican socialist artist, to paint the mural that was going to decorate the ground floor of the Rockefeller Center in Manhattan. The original sketches for the fresco were approved by the family, but an inciting headline from a famous newspaper changed everything. The Rockefeller family could not face the allegations of the article that they were supporters of the communist movement, which resulted in Rivera’s dismissal from the project, the destruction of his artwork, and protests in his support. Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads portrayed the never-ending struggle between capitalism and socialism in the form of a meticulously crafted artistic metaphor. This is the story of politics and free speech in the art world.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) was a Mexican artist whose works met the line between the artistic and the political. After studying at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, Rivera moved to Paris where he befriended Picasso and Braque and experimented with Cubism and the Post-Impressionism style. He married Frida Kahlo and completed a series of murals, mainly frescoes, using a centuries-old technique.

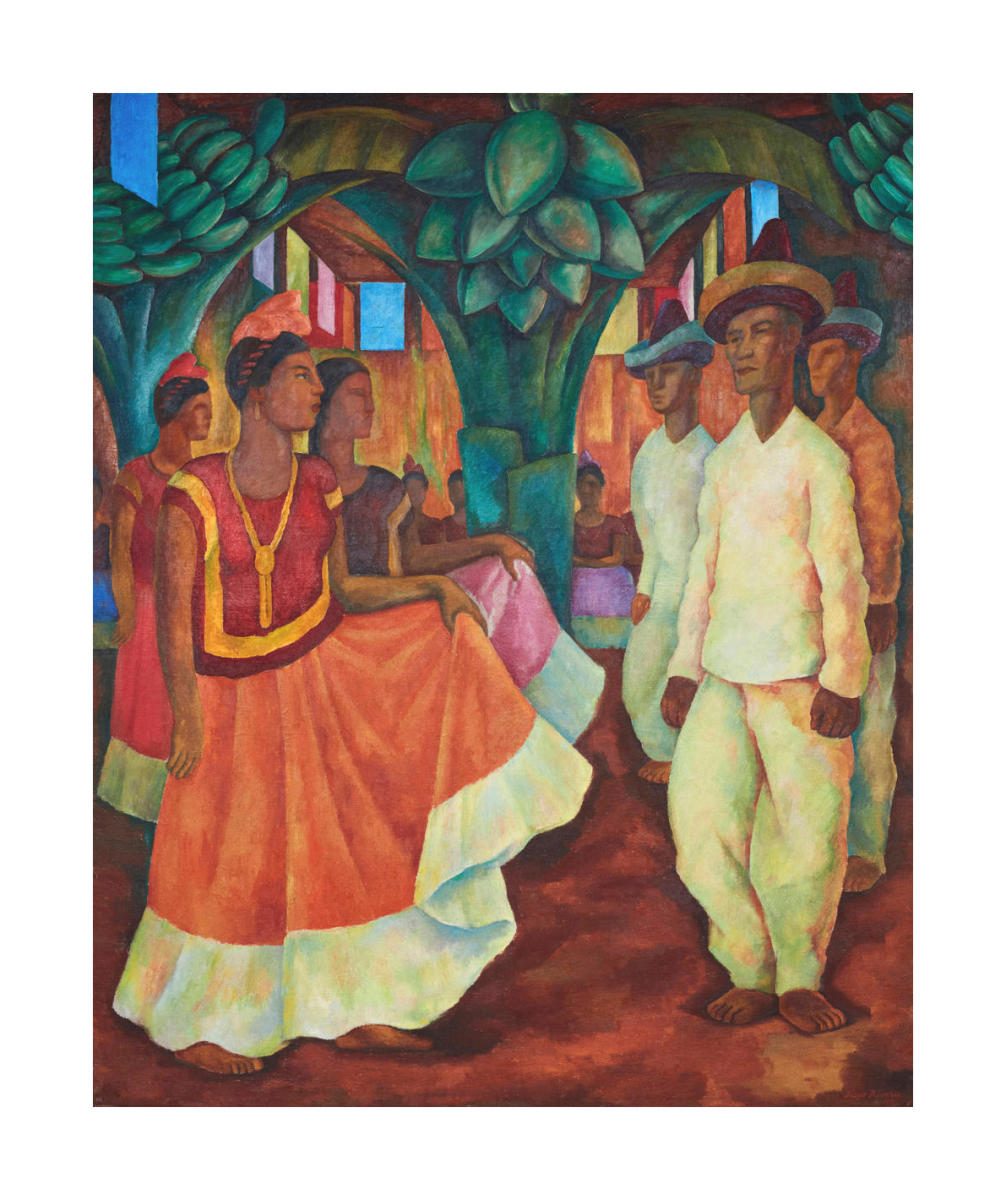

Together with José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), Rivera represented the faces of Mexican Muralism, which centered around revolutionary themes. His works include Dance in Tehuantepec, Detroit Industry Murals (a 27-panel mural fresco tribute to the city’s labor force), and Man at the Crossroads.

In 1932, Diego Rivera was commissioned by the Rockefeller family to create a painting for the ground floor of the Rockefeller Center in New York City. Rivera was one of Nelson Rockefeller’s mother’s favorite artists. The final product was designed to mentally challenge the viewer, hence the vision of three separate murals: The Frontier of Ethical Evolution, Man at the Crossroads, and The Frontier of Material Development.

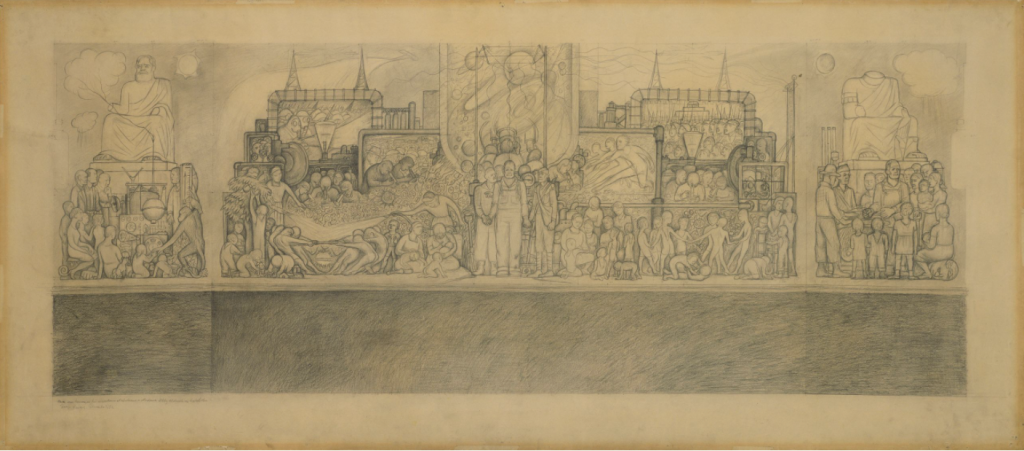

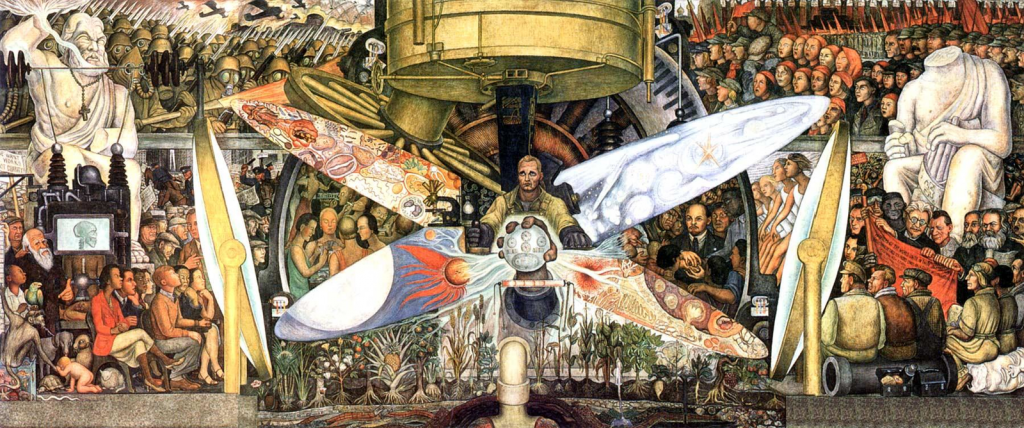

The central piece, Man at the Crossroads, creates a divergence between capitalism and socialism: Rivera masterfully illustrated the tensions between art and politics through components of society, industry, and science. Well aware of the rather controversial political subject at the time, The Rockefellers approved the originally proposed sketches by the artist.

The work on the mural started in 1933 and shortly after on the 24th of April, a strong headline from an article published by the New York World-Telegram newspaper unexpectedly hit the newsstands, accusing the wealthy family of supporting communist propaganda: “Rivera Perpetuates Scenes of Communist Activity for RCA Walls – and Rockefeller, Jr. Foots Bill”.

Just a few days after the incident, Rivera nonchalantly painted a new addition to his painting as a form of protest – the notorious political leader Vladimir Lenin. Of course, this precipitated bad publicity even more, and the family had to formally ask the painter to remove the new portrait. Rivera refused and stated that he would rather have his painting destroyed than alter it but proposed a compromise instead: he was going to add a famous American hero and President Abraham Lincoln.

This offer was discarded by Nelson Rockefeller. The opening of the new building, originally set for the 1st of May (coincidentally or not, May Day was chosen in 1889 by socialists and communists all over the world on International Labor Day to commemorate the struggles and gains of workers), was postponed and Rivera was asked to stop work on the project. He was paid in full and dismissed; the fresco was covered with drapery. Luckily, Lucienne Bloch, Rivera’s assistant, managed to take a few black-and-white photographs of the unfinished scandalous mural – in fact, they are the only remaining evidence of Man at the Crossroads.

A series of protests and demonstrations from artists across the country started soon after. E.B. White (1899-1985) wrote the protest poem I Paint What I See as a dialogue between River and Nelson Rockefeller to show his support for the artist’s cause:

I paint what I paint, I paint what I see,

I paint what I think, said Rivera (…)

I’ll take out a couple of people drinkin’ And put in a picture of Abraham Lincoln (….) But the head of Lenin has got to stay!

It’s no good taste in a man like me, Said John D’s grandson, Nelson. (…) For this, as you know, is a public hall. And people want doves, or a tree in fall,

And tho your art I dislike to hamper, I owe a little to God and Gramper.

And after all, It’s my wall… We’ll see if it is, said Rivera.E.B.White, I Paint What I See, The New Yorker, May 20, 1933, p. 29.

Even though certain advancements were made towards preserving and moving the mural to the Museum of Modern Art, in 1934, Rockefeller Center workmen removed the painting directly from the wall. Thus, one of the most fascinating and challenging pieces of work ever created within the Mexican Muralism movement was destroyed due to political misunderstandings.

Rivera’s mural was replaced in 1937 by American Progress, painted by the Spanish artist José Maria Sert (1874-1945).

The movement started back in the early 1920s in the wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1924) when the government commissioned artists to create art that would educate the illiterate population on the history of the country and present the envisioned future.

In an attempt to reunite the country, artists would make murals (i.e. fresco, encaustic, mosaic, or relief) on public buildings that would depict some of the newly created regional heroes such as natives, Aztec warriors, mere peasants, and glorious workers. The movement was motivated by the pre-colonial history of the country and hoped to cultivate a spirit of nationalism. The three leaders of the movement were Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros; they were also known as Los Tres Grandes.

Mexican muralism has not brought anything new to the universal plastic arts, nor to architecture, and even less to sculpture. But Mexican muralism – for the first time in the history of monumental painting – ceased to use gods, kings, chiefs of state, heroic generals, etc. as central heroes . . . . For the first time in the history of art, Mexican mural painting made the masses the hero of monumental art. That is to say, the man of the fields, of the factories, of the cities, and towns. When a hero appears among the people, it is clearly as part of the people and as one of them.

Diego Rivera, quote from Social Realism, New Masses & Diego Rivera, The Artifice.

Other famous artworks created within this movement include Prometheus by José Clemente Orozco, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie by David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Pan-American Unity by Diego Rivera.

The impressive fresco of monumental dimensions – to be more exact 4,80 x 11,45m (19,000 x 45,100 in) – depicts the societal struggles at the time by creating a comparison between capitalism and communism. Although a very agglomerated detailed work, the mural is separated into two halves by the central figure controlling machinery inventively placed as a vertical axis.

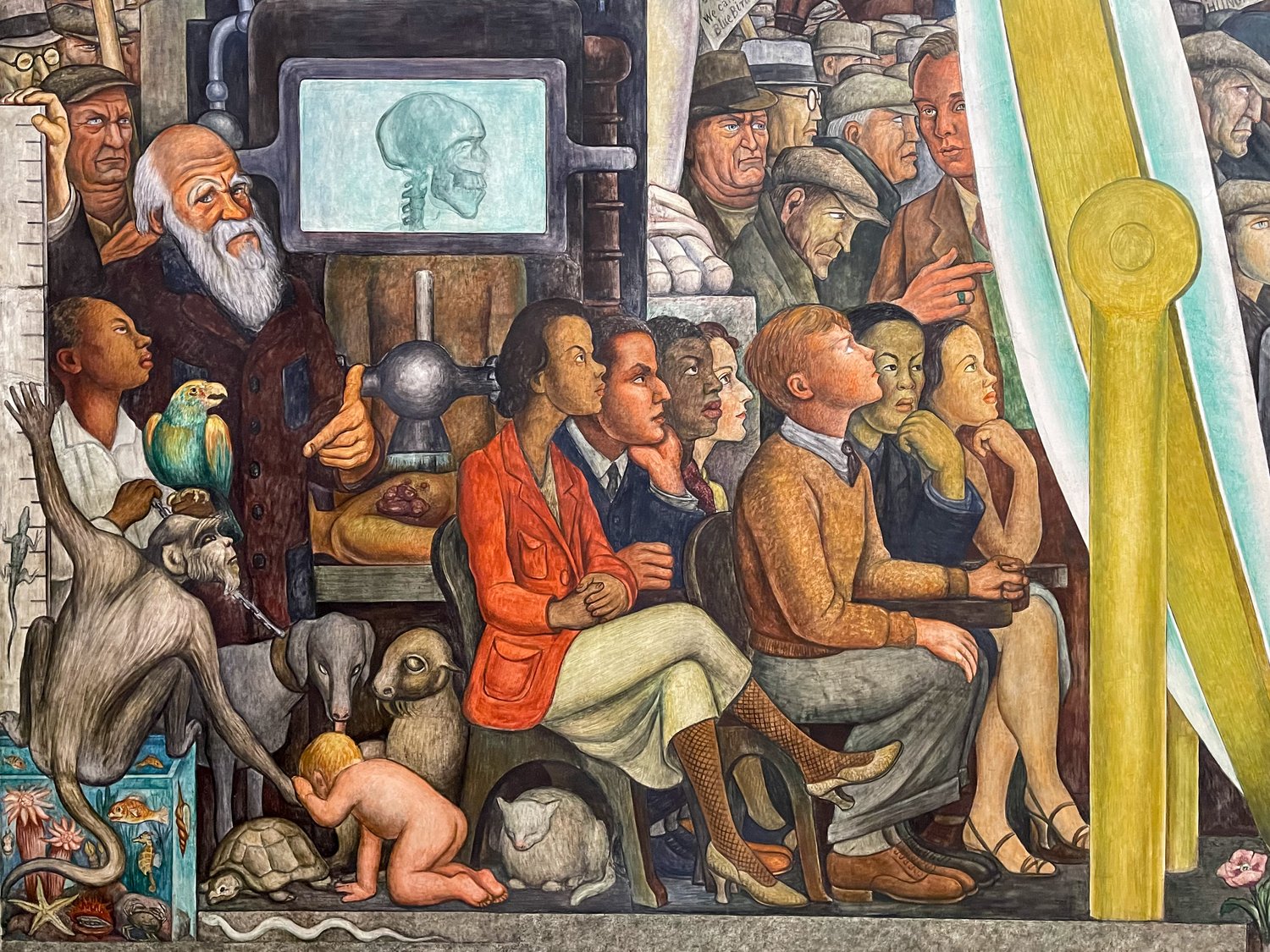

On the left, Rivera decided to display technology as a destructive force in response to the brutalities of World War I. As a critique brought to the political elite, the viewer can observe the wealthy playing cards while the world gruesomely unravels around it with NYC workers fighting the police in the background.

Meanwhile, the right side of the work overflows with abundance in the lower part – the fruits of communism. Influential political figures such as Trotsky, Engels, and even Marx himself are present in the tableau alongside the controversial political leader Lenin, who holds hands with workers of distinct ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Above this scene, the May Day rally is in full display with red flags and laborers gathered together to celebrate – a true tribute brought to the Russian Revolution.

Two salient elements from the compositions are the gigantic classical sculptures present on both sides of the mural. On the left, we can spot an angry Jupiter with a Christian cross and a thunderbolt in his arm that has been struck by a lightning strike. However, the right side portrays a decapitated Ceasar, and soon after, one can realize that several workers use the beheaded head as a bench to rest on. By grasping the oppressive nature of the elite over the popular masses, Rivera did not hesitate to imply in his work the overthrow of authoritarian leaders and the replacement of superstition and religion with science.

After the destruction of the mural, Rivera was able to create a smaller replica that now lies in the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, with the help of the photographs captured by his assistant. Regardless, Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads comes with a few modifications generated from Rivera’s fine sense of humor: John D. Rockefeller, Nelson’s father, is displayed heavily drinking in a nightclub with a woman. Above them, a dish with syphilis bacteria can be sighted.

The story behind Man at Crossroads sets an example in the art world by presenting a clash between the political and the artistic. Rivera decided to stay true to his values and not compromise his integrity as a painter. His work triumphed over any deliberate destruction and the passage of time.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!